Introduction

Human capital is a factor to the economic growth of a nation and helps determine its development trajectory.[1] Therefore, the task of human capital formation involves the development of people’s abilities, skills and experiences so that they can become productive resources in a society’s collective tasks to achieve progress and resilience.

While physical capital is extremely important, the effective mobilisation of these tangible assets crucially depends on the youth population that forms the foundation of an economy’s human capital. This can be enhanced through investments in modern education and skilling, adequate medical facilities, and political and civic participation.[2] Youths not only catalyse the positive transformation in the developmental patterns of the economy but are also stakeholders in reaping the benefits in the long term. While the UN SDGs play an important role in youth development, the realisation of these objectives also depends on their participation in the target areas of education and employment, health, and well-being, equality, and peace and security.

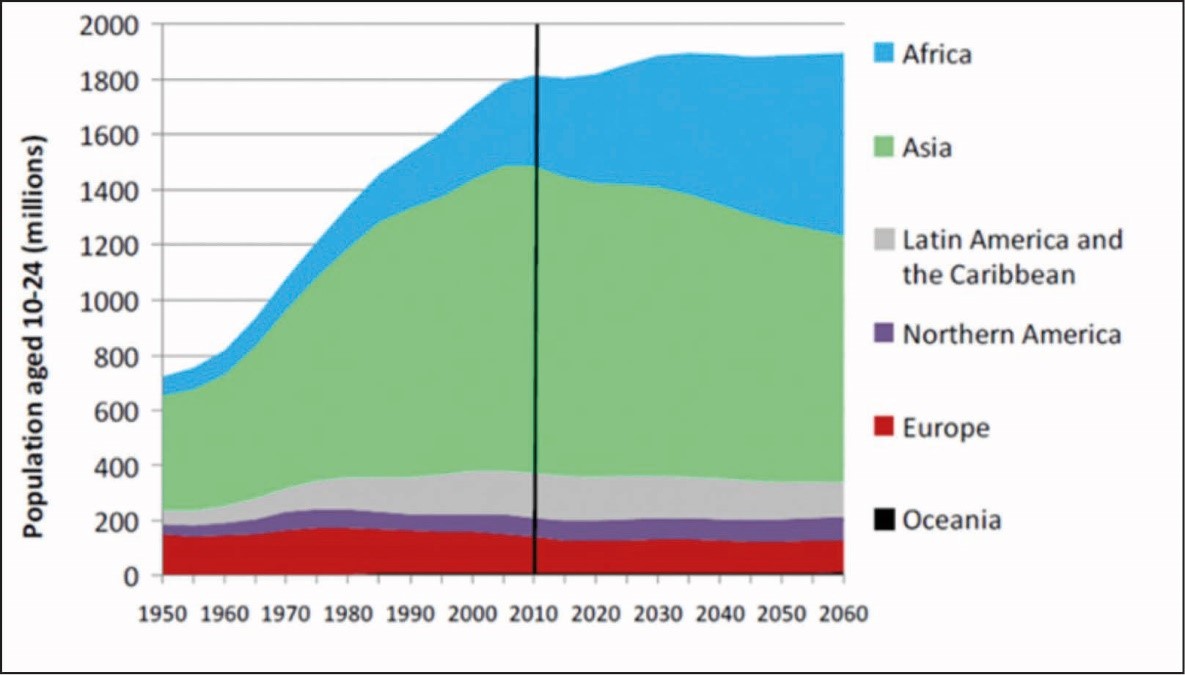

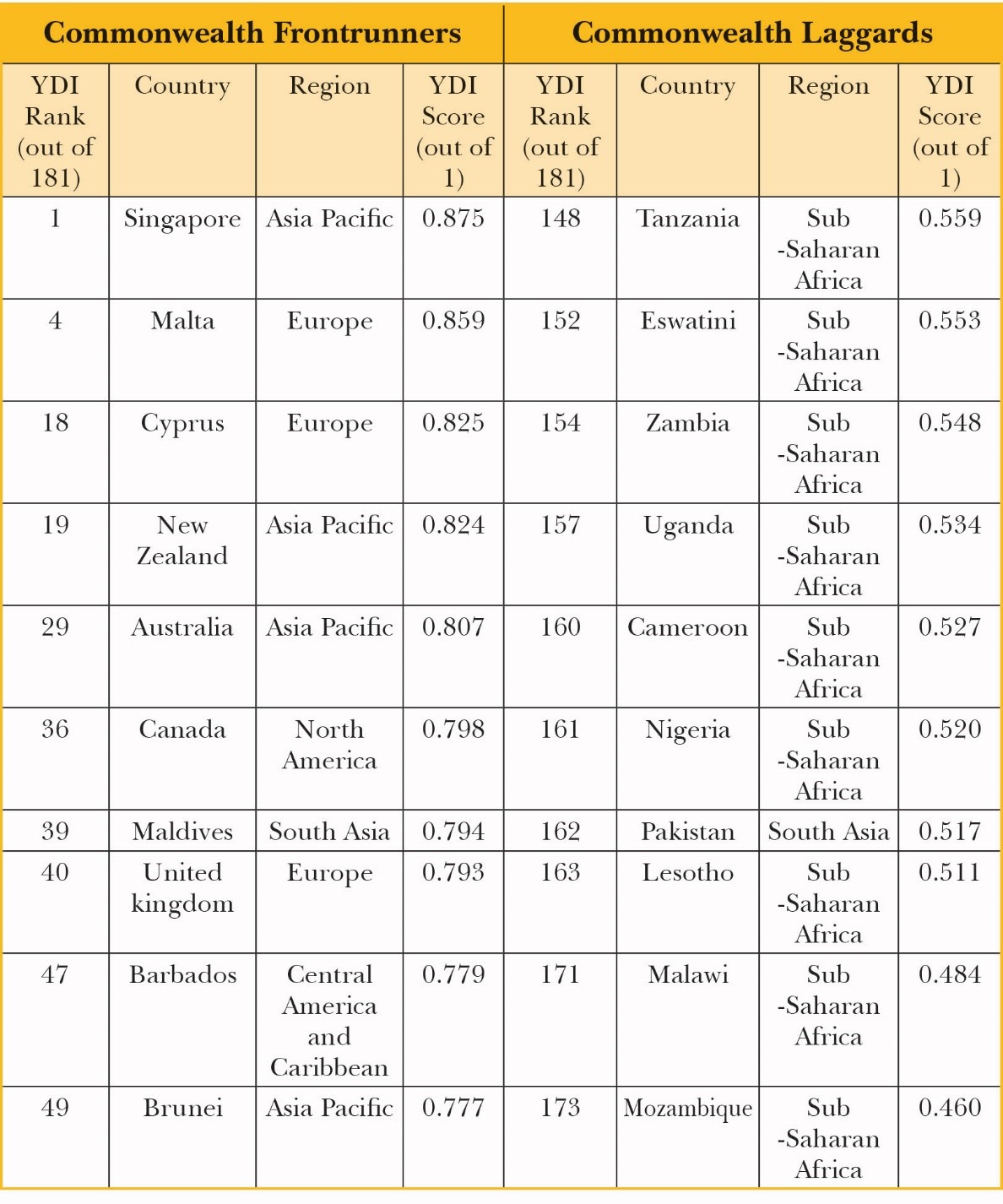

Almost half of the global population are younger than 30, and for the member countries in the Commonwealth of Nations,[a] 60 percent of its total 2.5 billion people fall in this age group.[3] This translates to a significant proportion of the population potentially becoming tools for economic progress and creating resilient communities. While Asia and Africa are home to the largest numbers of young people in the world, the age group of 12-24 years is expected to rise from 18 percent in 2012 to 28 percent in 2040 in Africa; Asia, meanwhile, is likely to see the sharpest decline from 61 percent to 52 percent during the same period.[4]

Figure 1: Regional Variations in Youth Population (Estimates, 1950 – 2060)

Source: Adolescent and Youth Demographics, United Nations Population Fund[5]

The Commonwealth federation focuses on the three main pillars of development, democracy, and peace for its member nations by strengthening domestic and global governance, building inclusive institutions, and promoting human rights and justice.[6] A current imperative is for youth-focused policies and investments. The Commonwealth was built on the core values of development of youths, and providing support to the small states. If acted upon, these values can provide the support necessary for the countries of the global South to push past their current levels of human capital development and lay the groundwork for future growth.

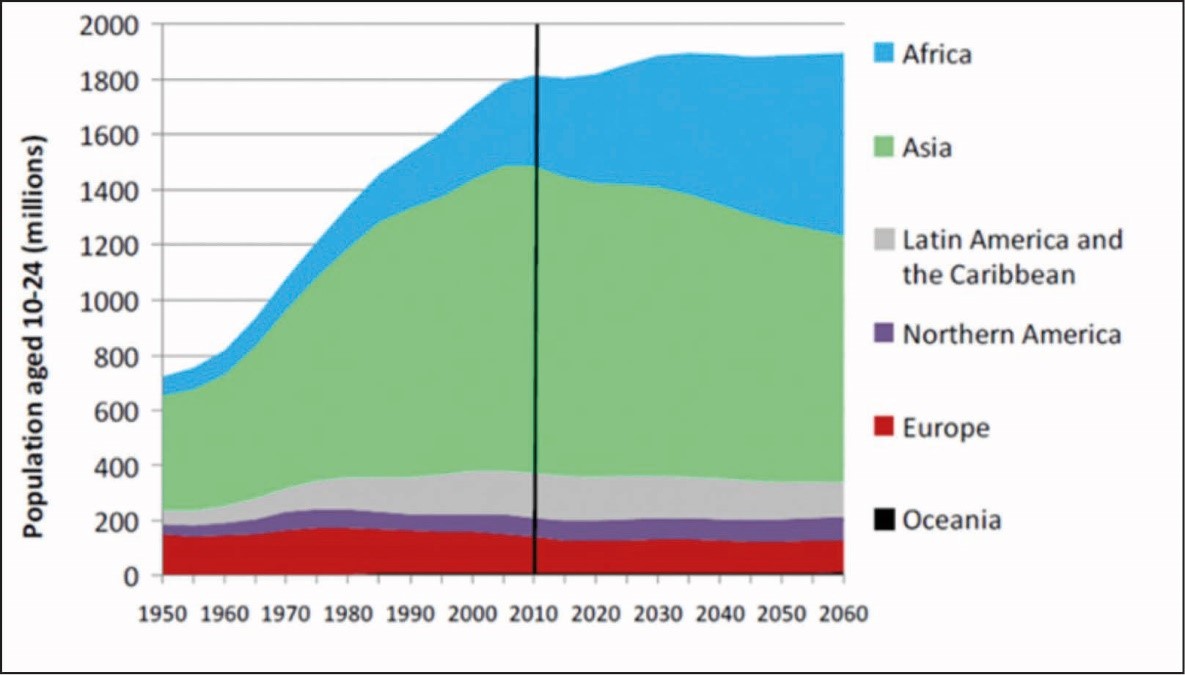

First, by engaging with youths and involving them in decision-making, the Commonwealth encourages youth participation. It provides technical assistance for national and regional youth policies and creates youth development frameworks. By supporting youth education and work, the member countries also promote the transition of the informal sectors of employment towards organised work. The Commonwealth also advocates for increased investments in youth ministries and programmes. Second, the heterogenous gathering of developed and underdeveloped nations in this region allows for dissemination of technological developments from the ‘technological leaders’ to the ‘technological latecomers’[7] –which is key to comprehensive youth capital advancements for digital transformations in a post-pandemic era. Governments at the national level, as well as supranational such as the Commonwealth, need to work simultaneously on easing technological imports from the global North.

1. The Commonwealth’s Youth Development Index

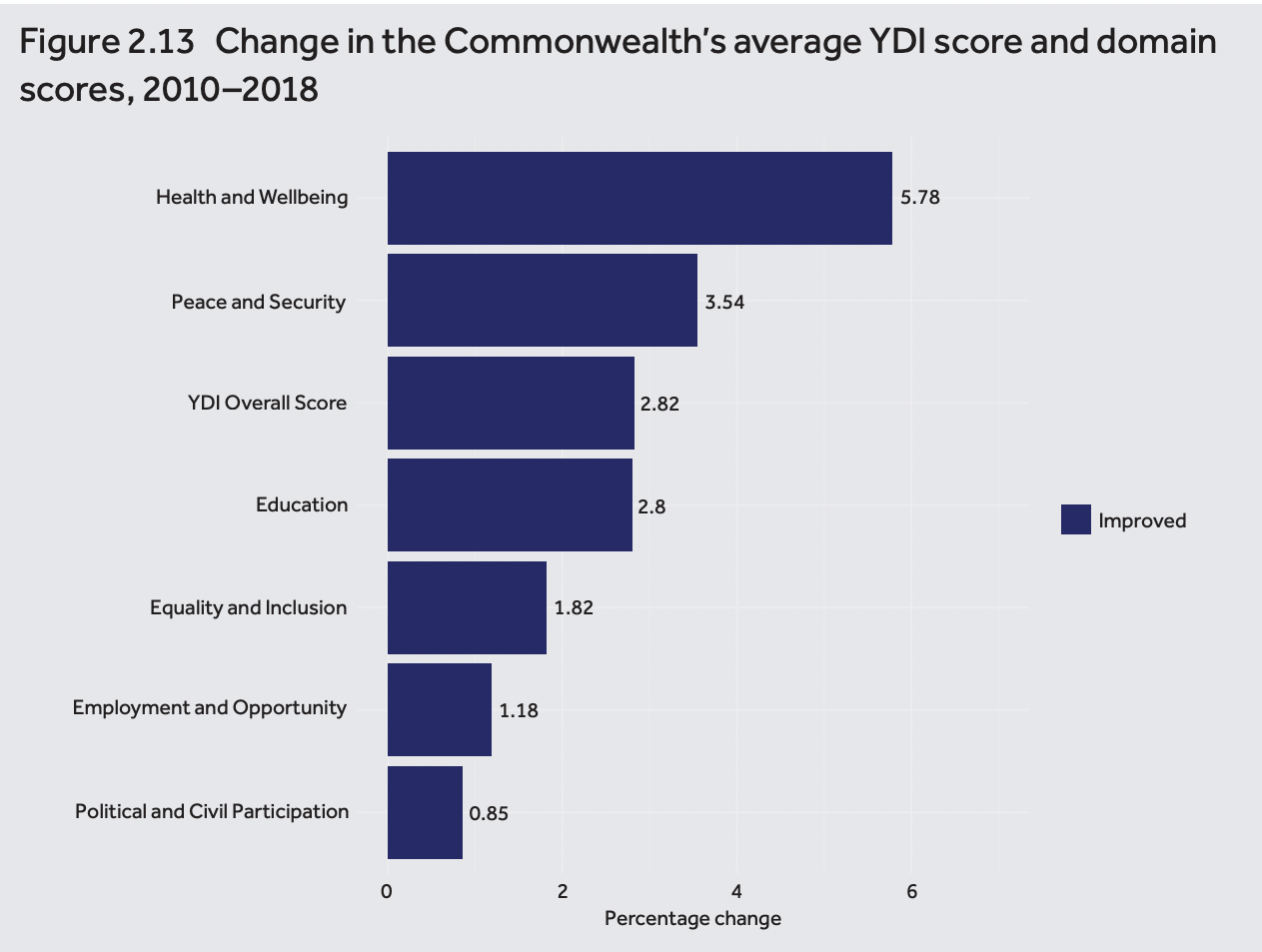

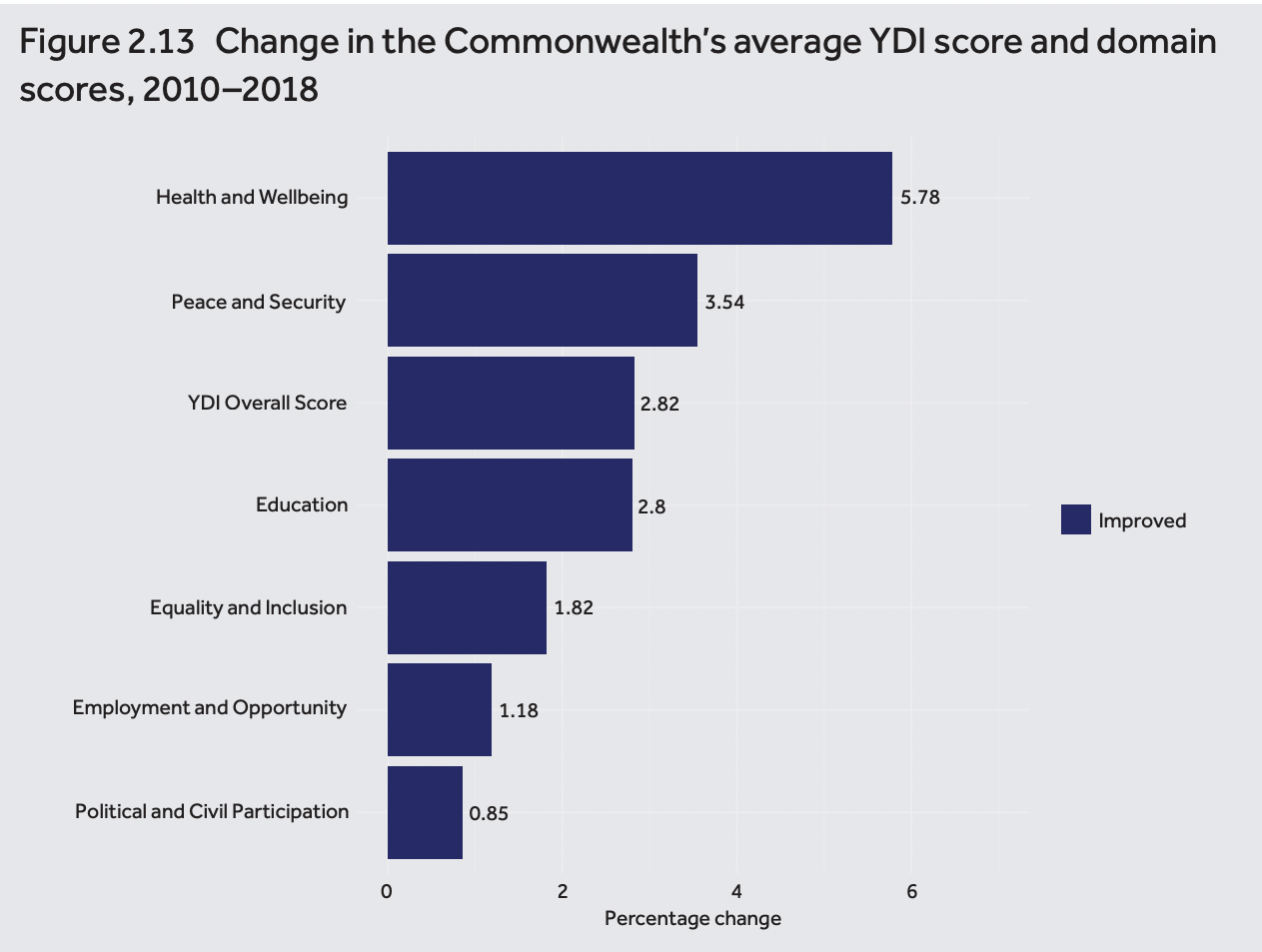

According to the Commonwealth Secretariat’s[8] 2020 Global Youth Development Index (YDI), the living conditions for the world’s youth have improved by 3.1 percent between 2010 and 2018. The index considers 27 indicators across 181 countries to measure the state of well-being of the world’s 1.8 billion young people.[b] The YDI determines how youths contribute positively to human capital advancements and uses variables such as change in employment patterns, education, health, equality and inclusion, peace and security, as well as political and civic involvement. The report cautions that absent urgent action, the COVID-19 pandemic could reverse the progress in youth well-being that has been achieved by the Commonwealth countries in recent years. It calls for increased investments for youths’ digital skill development, mental health services, apprenticeships, road safety, and their involvement in decision-making.

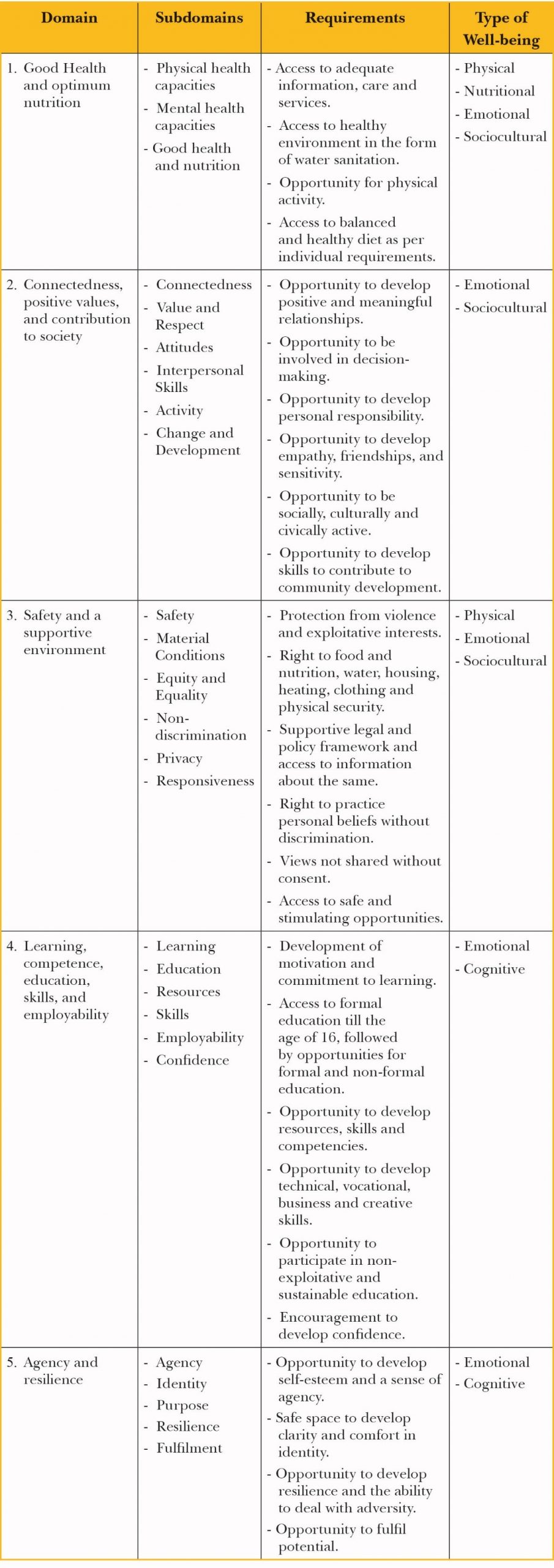

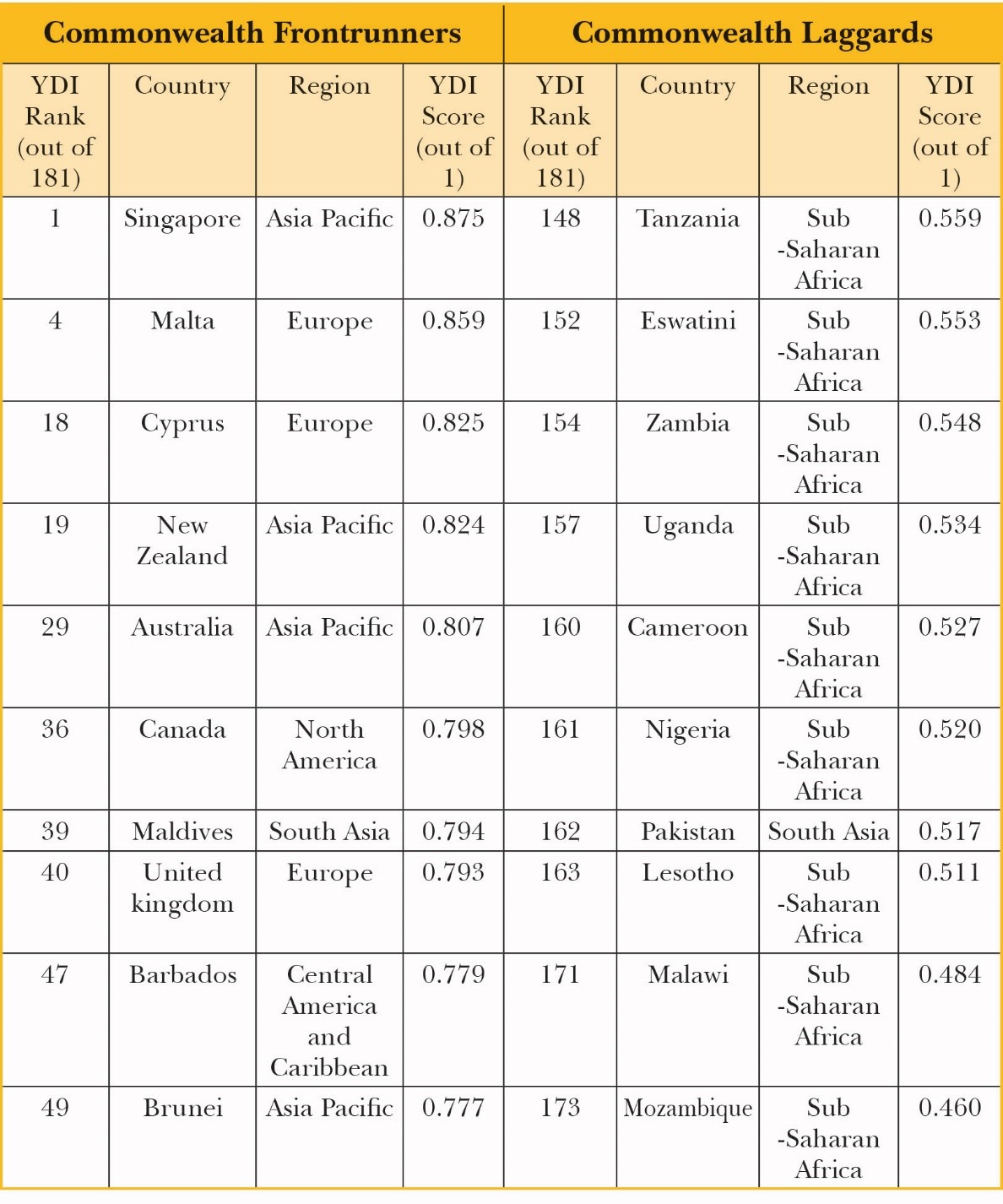

In the index, Singapore ranked first with a score of 0.875 (out of 1), and Chad came last with a score of 0.398. Meanwhile, Afghanistan, India, Russia, Ethiopia, and Burkina Faso are the top five countries that showed maximum improvement in youth development, and Syria, Ukraine, Libya, Jordan and Lebanon recorded the sharpest decline. Among the Commonwealth nations, Singapore (1), Malta (4), and Cyprus (17) were the frontrunners; at the bottom were Lesotho (163), Malawi (171), and Mozambique (173) (see Appendix 1). Overall, the average scores for the Commonwealth grouping showed improvement in all the parameters considered in the index (with a 2.8 percentage point rise in YDI scores between 2010 and 2018). The highest improvement was in health and well-being (where Sub-Saharan Africa has emerged with the highest score), while youth’s political and civic participation deteriorated in 102 nations.

Figure 2: Change in the Commonwealth’s Average YDI and Domain Scores (2010-2018)

Source: Global Youth Development Report 2020, The Commonwealth[9]

2. Youth in the SDG Framework

The formation of youth capital, as envisioned by the SDG framework, is an integral part of a country’s development and the primary force behind economic improvement for resilient societies. The combination of accumulated skills and goals, of which education is perhaps most important, also contributes to the enhancement of social assets. These assets, in turn, help create a congenial business climate due to favourable labour market conditions, digital skills, increased capital investments, and better mobilisation of resources—all of which are critical for development. While digital skill development is important, the challenges in mitigating gender- and class-based digital divide need to be addressed to achieve better results.

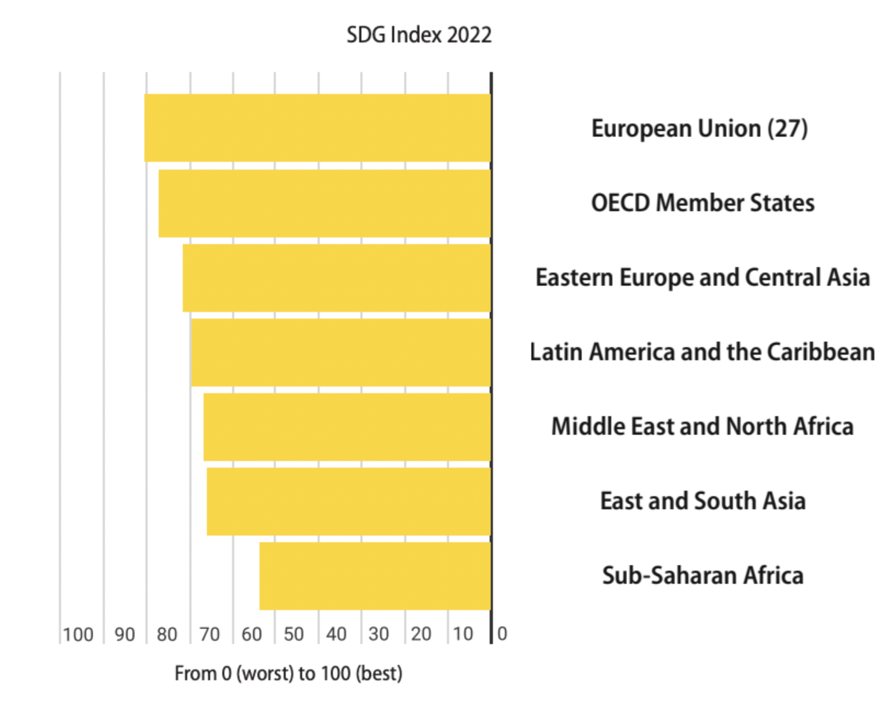

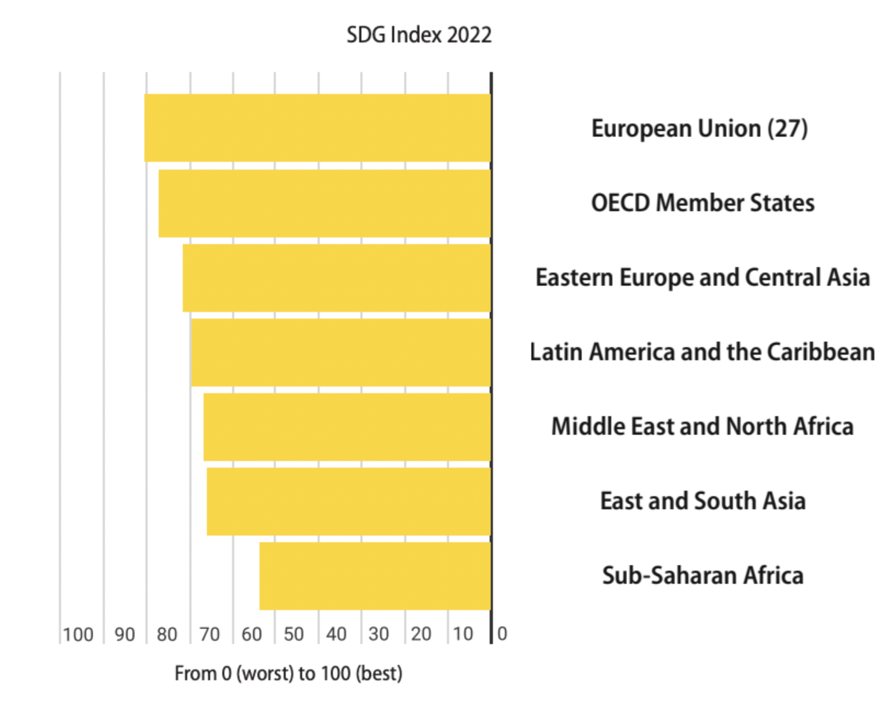

Using education data for 55 countries and regions from 1960 to 2009, an econometric analysis underscored a positive correlation between the economic growth of a nation and capital investments in education.[10] Though indicators such as health, education and income have seen improvements over the past few decades, the developing world finds itself falling far behind the advanced nations when it comes to achieving the common objectives of the SDGs.

Figure 3: Regional SDG Index (2022)

Source: Sustainable Development Report 2022, Bertelsmann Stiftung, SDSN and Cambridge University Press[11]

Without the active participation of the youth, the goals under the 2030 SDG Agenda cannot be met.[12] It is for this reason that youth development monitoring frameworks are crucial in keeping track of progress (or the lack of it). The UN Youth SDG Dashboard aims to serve this purpose and tracks indicators across different targets.[13]

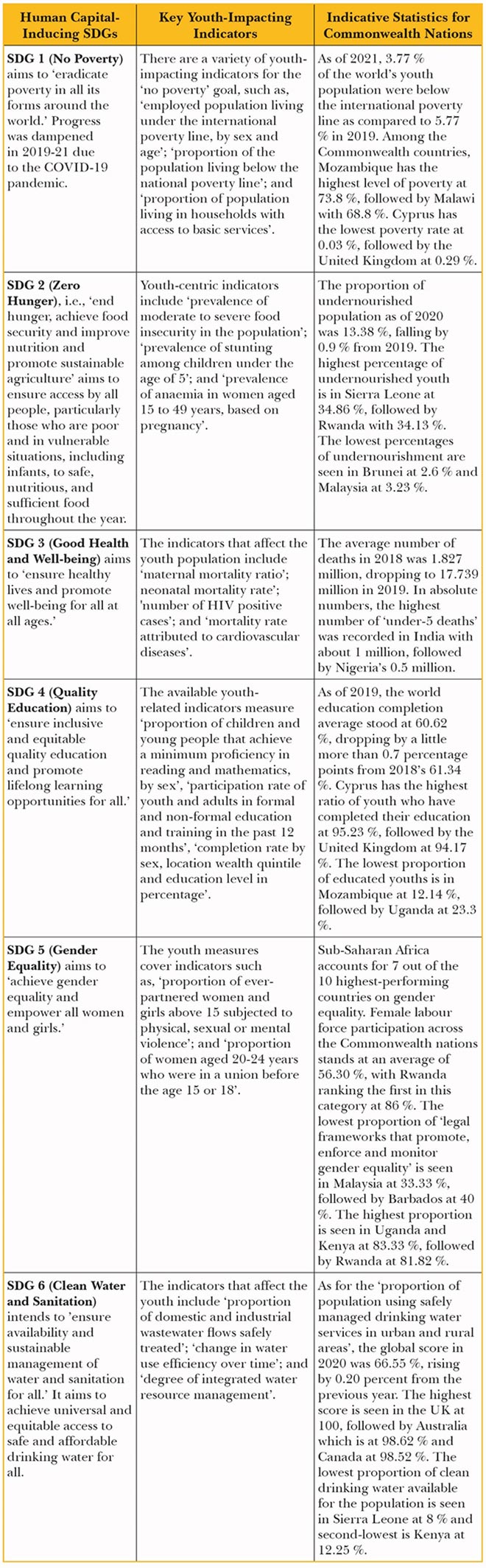

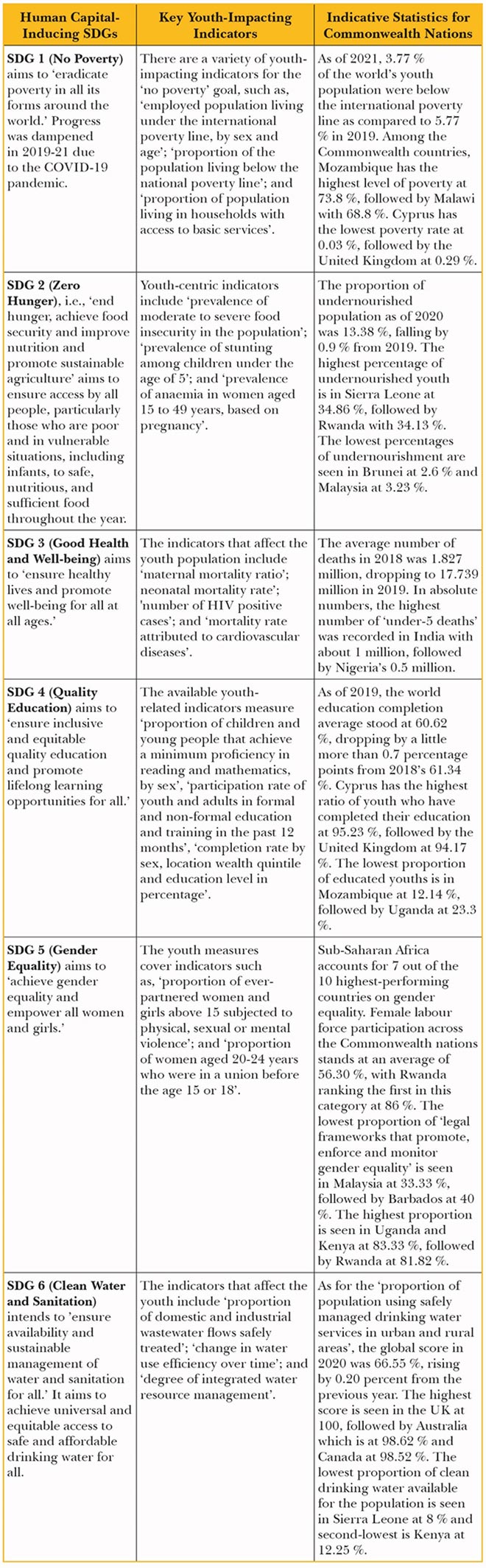

Focusing on achieving the goals can help improve the input and product market conditions[c] and promote business competitiveness in post-pandemic economies. SDGs 1 to 6 (no poverty, zero hunger, good health and well-being, quality education, gender equality, and clean water and sanitation) are concerned with demographic parameters that improve labour market conditions, in turn enhancing the social and human capital aspects of youth development.[14]

Table 1: SDG Indicators with Direct Impacts on the Youth Population

Source: Author’s own. Data from: United Nations;[15] UN Youth SDG Dashboard;[16] the UN Sustainable Development Report, 2022;[17] and The Commonwealth Fast Facts[18]

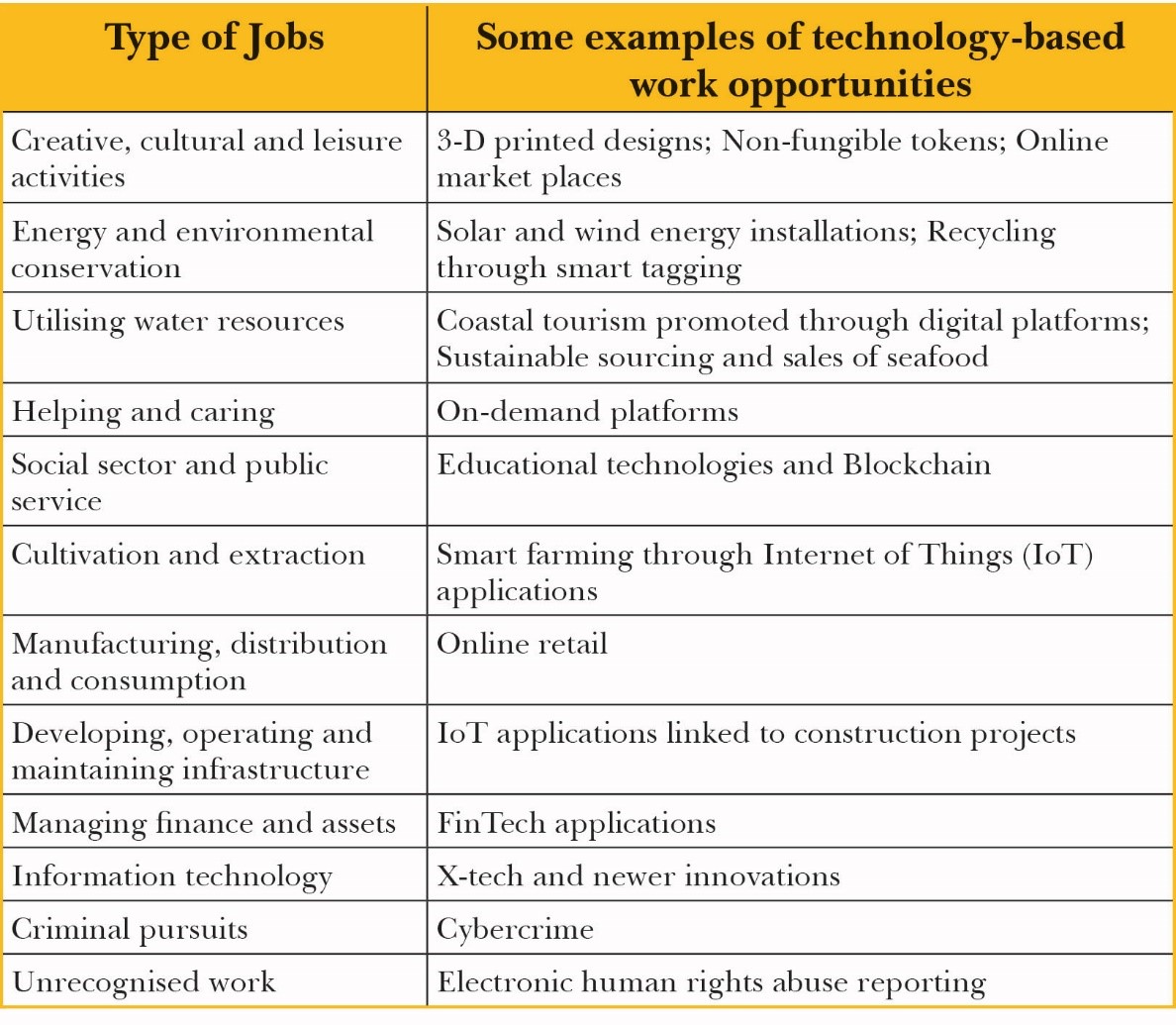

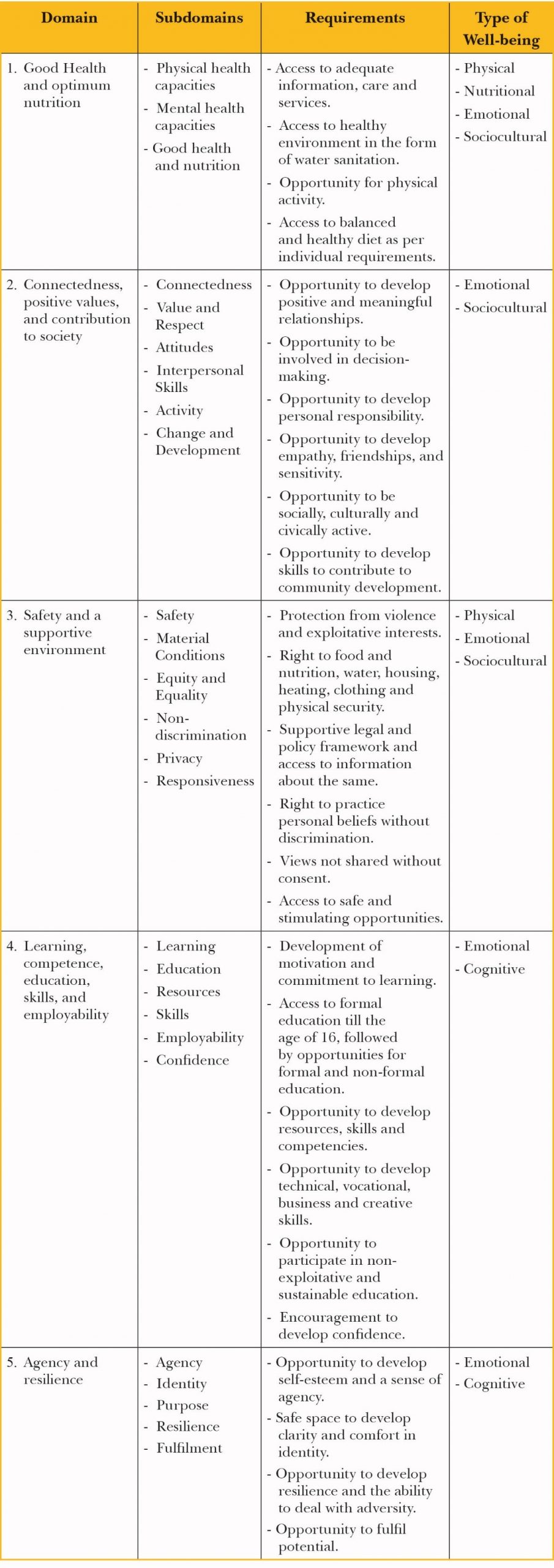

2.1. SDG-3 and Youth Well-being

In addition to advancing human capital, investing in the youth is also crucial to adopt a well-being approach. Ross et al (2020)[19] have created a framework to define the different domains of adolescent well-being (see Appendix 2). This includes parameters such as good health and nutrition, skills, and employability. While physical and mental health are important aspects of well-being, as indicated under SDG 3, broader definitions of ‘well-being’ include a number of other aspects that are both subjective definitions focused on personal experiences, and objective definitions covering overall quality of life.[20]

SDG 3 (good health and well-being) focuses on the need to advance health and well-being, specifically highlighting that this must cover all age groups. This becomes exceptionally crucial for the youth, especially during adolescence.

The Commonwealth Youth Plan of Action for the period 2007-2015 focused on the concept of well-being since it is based on the human rights approach to youth development which seeks to address the imbalance in power equations as well as discrimination, by advocating for the rights of marginalised groups.[21] In the context of youths, this would mean empowering them through skills and opportunities to contribute actively towards their own development and for societal progress. The Plan of Action underlines the goal of “mainstreaming the youth”—i.e., governments should allocate specific budgets for youth development, introduce youth development perspectives to relevant departments, set up mechanisms for the youth to participate in policymaking, monitor and report progress made by youths, and build the body of knowledge related to their empowerment.[22]

The Commonwealth Global Youth Development Index 2020[23] covers various aspects that overlap with the Commonwealth’s identified domains of “mainstreaming the youth”. For instance, the pillar of ‘peace and security’ in the YDI overlaps with the domain of ‘safety and supportive environment’ included in the conceptual framework on adolescent well-being proposed by Ross et al (2020).[24]

The World Youth Report published by the UN Agenda for Sustainable Development tracks the progress in the various youth-related SDGs.[25] While SDG 3 specifically talks about the well-being of youths, other youth-specific SDGs must be achieved in parallel. The report estimates that the achievement of youth-related sustainable development objectives will require a sharp increase in financing. Indeed, there is a shortfall of around US$ 39 billion for education alone.

3. Building Resilient Societies in the Commonwealth

The United Nations General Assembly defines ‘resilience’ as “the ability of a system, community or society exposed to hazards to resist, absorb, accommodate, adapt to, transform and recover from the effects of a hazard in a timely and efficient manner, including through the preservation and restoration of its essential basic structures and functions through risk management.”[26] In a contemporary context, building resilient communities across the Commonwealth nations must take into account their cultural and geographical diversities, as well as the impacts of climate change, urbanisation, globalisation, technological advancements, and demographic changes.

The SDGs make specific mention of how resilience needs to be created in societies to achieve equitable progress by 2030. Within SDG 1 (no poverty), target 1.5 discusses the need to build resilience among the poor to help them withstand environmental, economic, and social disasters.[27] While SDG 9 (industry, innovation and infrastructure) requires resilient infrastructure to be built, and inclusive and sustainable industrialisation to be promoted,[28] SDG 11 (sustainable cities and communities) includes making cities and settlements inclusive, sustainable, and resilient.[29] The youth have hitherto had a limited role in city planning and organisation, if at all.[30] With a majority of the world’s young population either living in or aspiring to live in cities not only in the Commonwealth countries but globally, the plight of urban areas is critical to achieving SDG 11.

Resilient societies are traditionally viewed as those that are capable of rising from the impacts of exogenous shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the Ukraine–Russia conflict. Such an approach views resilience as a coping response rather than as a defence mechanism—therefore putting the heaviest burden of imbibing resilience on the poorest and most vulnerable and marginalised in society. Resilience-building should instead be viewed as a multidisciplinary approach that would focus on capacity building for people and communities. Creating such an inclusive model for the Commonwealth nations would require focusing on the most vulnerable populations, and on categories that hold the most power for the transition towards more resilient societies. The youth are one such demographic capable of robust capacity-building and sustainable change.

First, the demographic dividend of a nation refers to the shifts in a nation’s economic potential when the population’s age structure experiences changes.[31] A positive change can occur when the working-age population is larger than the non-working-age population. The idea is to involve more youths in the working population of the Commonwealth through skilling and other social security measures, thus stimulating economic progress in the longer term. A UN report shows that for developing countries such as India to reap their demographic dividend, two kinds of investments are required.[32] Human capital investments are historically lower in these economies than in developed nations. An improvement in this regard, especially for children and adolescents, would yield favourable results. Education was found to be an investment with one of the highest economic returns.[33] Building a well-functioning public health system and improving access to the same is another crucial task for governments in the Commonwealth countries.

Second, the pandemic has led to increased technology penetration across the world, and trends indicate that these numbers will only grow in the future.[34] Enabling the Commonwealth’s youth to adapt to technological innovations can help create a future-ready workforce.[35] Third, SDG 17 (partnerships for the goals) focuses on building partnerships amongst nations and with the UN towards achieving the Development Agenda 2030.[36] Given that Commonwealth countries are home to around one-third of young people in the world ages 15–29,[37] the youth are integral to the effort towards this goal. Building on existing initiatives, advancing current contributions, improving youth participation, and promoting professional mobility, are only some of the tasks that need active youth involvement.

Finally, while global warming has had negative consequences on all the Commonwealth member states, the 32 small states that include 25 Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and 12 Least Developed Countries (LDC), are particularly vulnerable.[38] The cascading impacts of warmer oceans, sea level rise, changing weather patterns, coastal erosions, cyclones and natural disasters like floods and droughts have derailed progress towards the SDGs. Against this backdrop, the youth of the Commonwealth nations should be leveraged in terms of rapid transition towards low-carbon lifestyles and technologies that can have a significant impact on mitigation and adaption strategies for climate action (SDG 13).[39]

4. Investing in the Youth

4.1. Education

An urgent imperative is effective investment in areas that would benefit youths the most to enable sustainable economic growth and societal development. Research considers education and health as two of the most essential elements in human capital investment:[40] a healthy and educated person would be able to work more efficiently and add to economic productivity.

There is no dearth in literature championing youth education as key to human capital formation. For example, T. Schultz’s seminal paper (1961) highlighted the role of education in facilitating the growth of human capital.[41] Kiker (1966)[42] later identified this in the work of other prominent economists such as A. Marshall (1920)[43] who had emphasised the significance of skills and knowledge as an important tool for economic development. Becker (1964)[44] and Mincer (1984),[45] for their part, showed how investment in human capital could influence future real incomes.

Education is a key element of human capital theory because it is viewed as the primary means of developing knowledge and is therefore a way of quantifying the quality of labour. Mincer (1974)[46] is credited with developing the core model designed to explain differences in individual income as a function of the level of education and work experience for the young. More recent studies by Mankiw, Romer &Weil (1992)[47] and Lucas (1988)[48] stress on the essential role of education as the primary factor in increasing human capital and encouraging economic growth by helping individuals acquire knowledge, exposing them to job opportunities, developing social interactions, making them more aware of their rights, improving health, and reducing poverty.

UNESCO reports published after the 1990s document the persistent historical divide in education between the global South and North.[49],[50] For example, net enrolment rates for primary school students in developed nations have hovered around 95 percent, while developed and developing nations have lagged behind. Similarly, the number of years students spend in school is far lower for developing countries, with a difference of over five years even in 2008.[51] Many Commonwealth nations in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa currently fall behind North American and European nations by a huge margin.

The COVID-19 pandemic has only worsened the divide. As pandemic-induced restrictions became the norm globally, schools had to shut down, impacting the SDG 4 targets for quality education. However, certain groups of nations were able to open up earlier than others owing to better health infrastructure and advanced educational facilities. For example,[52] by October 2020, school children in advanced economies had lost approximately six weeks of school on average. The number is a far higher four months of schooling lost for low- and lower-middle-income countries, since the beginning of the pandemic. Mitigating the differences in losses in education between the developed and the developing world is more important than ever in a post-pandemic world as it could help determine the long-term macroeconomic structure of economies.

Furthermore, as physical access to educational institutions prevented students from attending schools during the pandemic, improving telecommunication and internet penetration in remote areas became more crucial.[53] When paired with better access to affordable technology, this has the potential to improve universal access to education in the post-pandemic world. First, public funding needs to be deployed to bridge the demand-supply gap that prevents digitisation of education and work spaces; and second, remote learning infrastructure needs to be built to ensure that the poorer countries do not lag too far behind in the sectors of education and skilling outreach.

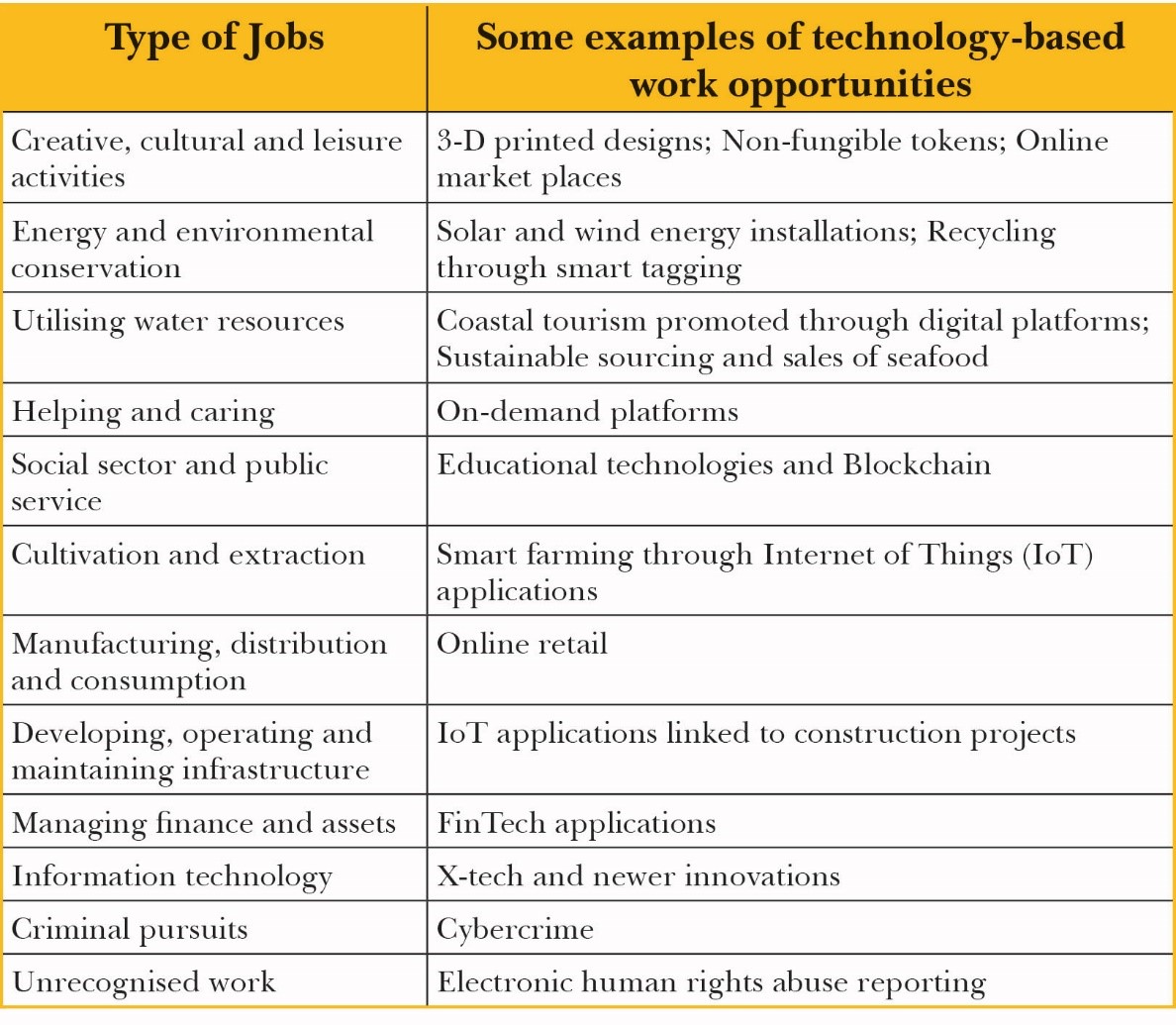

For the Commonwealth nations, almost half of the countries had scores on education which are consistent with ‘high and very high’ levels of youth development from 2010 to 2018.[54] While the pandemic disproportionately impacted educational and employment opportunities of young women, it also managed to create new opportunities in the sphere of online jobs and virtual workspaces.[d] In the current times, greater attention is needed for skilling techniques that help young people take advantage of the digital era (see Appendix 3).

Both neoclassical and endogenous growth theories explain poverty in developing countries in terms of differences in technology levels. The aim of technology diffusion should be helpful in attaining economic convergence between the Commonwealth countries which are driven by trade in technology.[55] The gap in cross-country income levels in the Commonwealth will narrow if technologically younger nations are able to upgrade their science and technology domain at a faster rate than the advanced nations. The potential level of technology that can be achieved by the ‘technological latecomers’ in the Commonwealth would depend on their domestic educational achievements characterised by the digital skill level, and imports of the digital advancements from the ‘technological leaders’.

4.2. Health

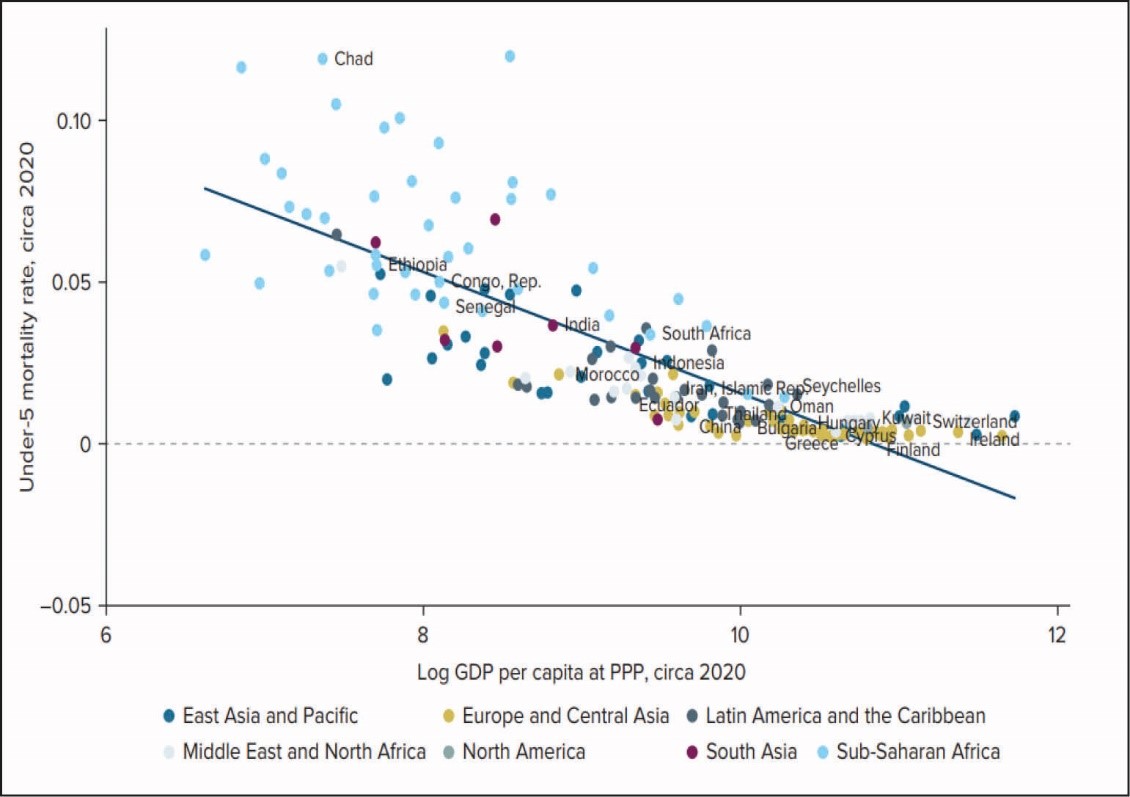

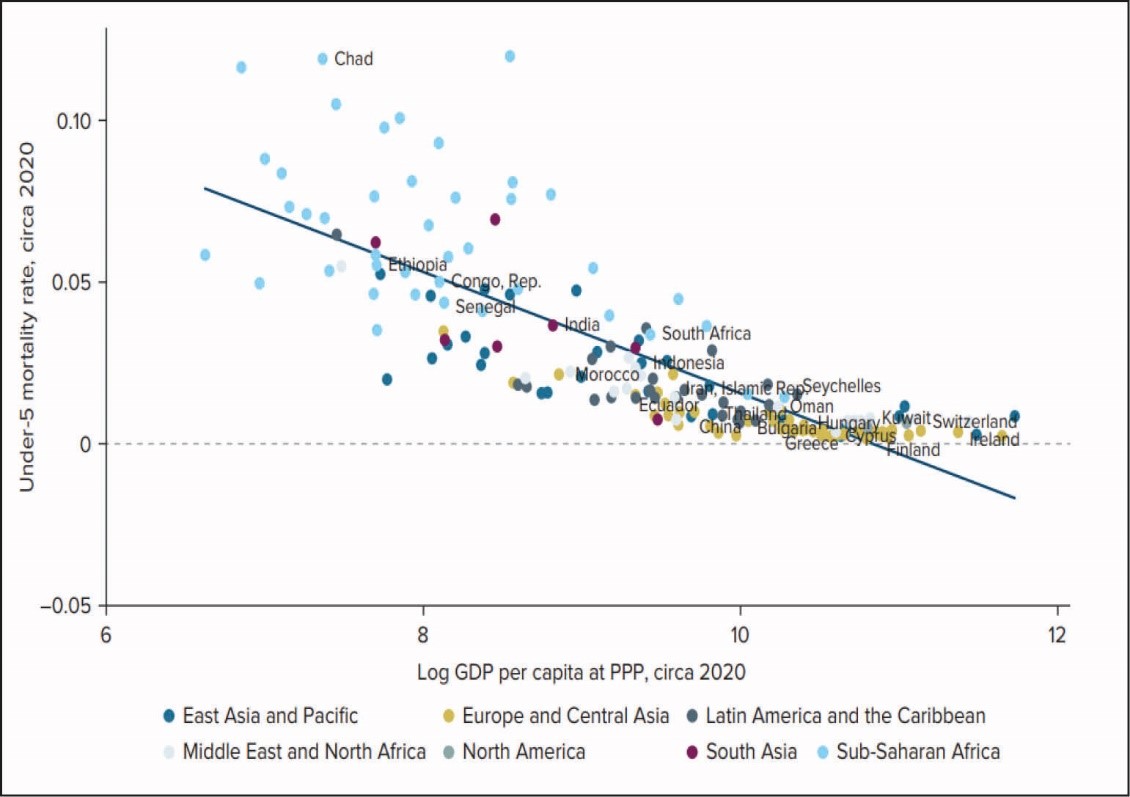

Panel data analysis for 118 developing countries from 1971 to 2000 found that improvements in health conditions have measurable benefits to the economic prospects of a nation.[56] If investments lead to an increase of a single year to the population’s life expectancy, it could be associated with 4 percentage points of higher growth.[57] A higher degree of access to formal banking systems, and improvements in health, fertility and technology adoption were noticed when developing nations showed improvements in schooling numbers.[58] World Bank data shows that when it comes to under-5 mortality rates, there is a seven-fold gap between low- and high-income countries that is directly correlated to diverging per-capita GDPs.[59]

Figure 4: Under-5 Mortality and Per-Capita GDP, by World Regions, 2020

Source: The Human Capital Index 2020 Update, World Bank Group[60]

An indicative relationship between a nation’s economic prowess and its health outcomes is also apparent for the African nations that have higher mortality rates and are seen on the worse end of the spectrum. In contrast, European, Central Asian and Pacific countries are recording far lower mortality rates—with such progress being assisted by higher levels of public health investments fuelled by economic progress. In the pre-pandemic era, countries like France, Switzerland and Germany invested over 11 percent of their GDP in the public healthcare system.[61] India’s investment in healthcare remains low, and it is unlikely to achieve the goal of 2.5 percent of GDP by 2025, as envisioned by the National Health Policy, 2017.[62] Investments in youth-oriented programmes that address unhealthy habits like smoking as well as poor dietary habits would result in the inculcation of practices that can have lifelong personal benefits and long-term macroeconomic implications.

Needless to say, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has dampened earlier progress in the sectors of health and well-being due to restricted movements and an overstretched health system. Although there was marginal improvement between 2010 and 2018 in issues that have long plagued the young generations—e.g., HIV infection, alcohol abuse, self-harm, and tobacco use—the Commonwealth recognises the contributions of the youth in advancing good health. The Commonwealth’s YDI 2020 report highlights two specific youth-centric areas that require attention:[63] legislation on youth’s access to mental health services, which has gained more relevance amidst the pandemic with higher levels of educational disruptions, isolation and unemployment; and an alarming incidence of fatal road accidents.

The World Bank has observed how children born today in the poorest nations will only reach 30 percent of their human capital potential, while those in the wealthiest economies have a corresponding figure of 80 percent.[64] Since the returns to physical capital eventually diminish, it is the human capital that will play a key role in the economy’s growth.[65] Such results underline the need for improvements in health facilities to benefit nations in the global South. Therefore, partnerships between the developing and developed nations within the ambit of the Commonwealth could lead the way towards the common objectives of SDG 3 (good health and well-being). Careful registration and data tracking will also be necessary in the post-pandemic scenario, especially as more than half of the Commonwealth nations are lagging behind in this aspect.[66]

5. Inclusion, Participation, and Peace

The pandemic has disrupted education, skills training, economic mobility, and health and wellness for many young people across the globe. The crisis has only widened the already existing gender disparities and poses a risk of undoing the progress recorded in recent years in reducing gender pay gaps. In different parts of the world, the pandemic also made young girls and boys more vulnerable to domestic violence.

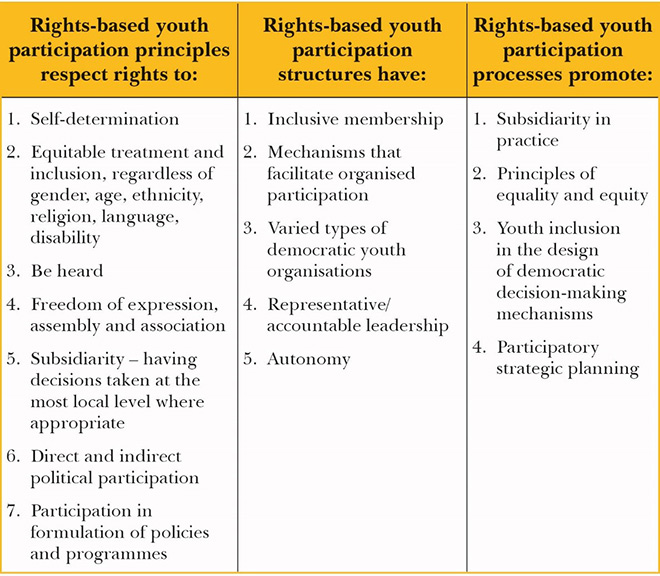

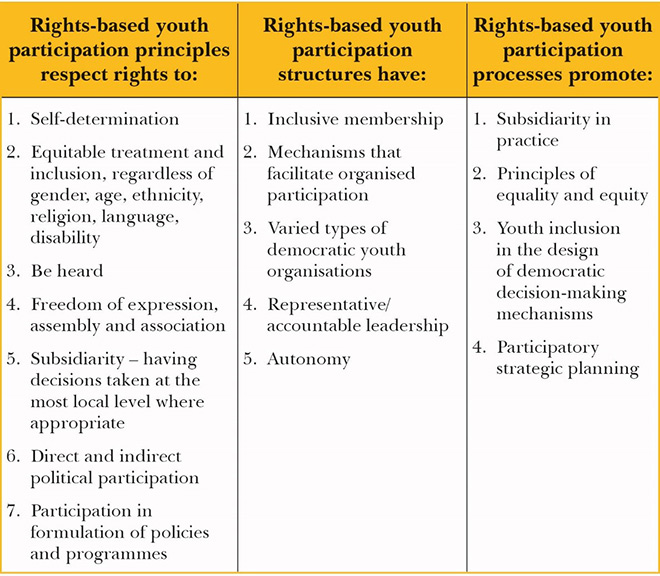

Societies become more inclusive when young people, individually and in groups, are able to engage in political and civic issues in their communities. Gun violence, cybercrime, housing shortage, immigration, environment crises, and lack of healthcare, are among the many issues that disproportionately affect the young. However, voter turnout among the age group of 18-25 years continues to be lower than in other age groups.[67] In order to achieve an inclusive recovery and a sustainable future for the Commonwealth nations, global and domestic policies must prioritise unleashing the youth’s potential as productive members of society.

Table 2: Principles, Processes, and Structures of Rights-Based[e] Youth Participation

Source: Global Youth Development Report 2020, The Commonwealth[68]

With improved security across countries, fewer young people lost their lives from violence such as homicide, armed conflict, and terrorism in the last decade. However, developing countries could suffer a setback because of increased border skirmishes in certain parts of the world and the ongoing Ukraine-Russia conflict. According to UN Globe Population Prospects figures, there are 1.3 billion people in the world between the ages of 15 and 24, with nearly one billion of them residing in developing nations where armed conflict is more likely to have occurred.[69] The youth are among the first groups to suffer from radicalisation and war, and therefore, their involvement in conflict prevention and resolution is crucial in efforts to nurture lasting peace.

SDG 16 (peace, justice and strong institutions) aims to “promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels.”[70] The objectives include significant reduction in all forms of violence and related deaths, ending abuse, exploitation, trafficking and all forms of violence against and torture of children. For example, the indicator ‘proportion of population that feel safe walking around the area they live in’ gives an insight into the peace and inclusiveness experienced by the world population. While little data is available on this specific indicator for all countries, the highest scores among the Commonwealth countries are seen in the UK and Canada.

6. The Role of Commonwealth Youth Programmes

For 40 years, the Commonwealth Youth Programmes (CYP) have disbursed the Commonwealth Secretariat’s youth development work through the network of 56 countries. The main goal of the CYP is to ensure the effective participation of young women and men in the nation’s development processes while also improving youth engagement in decision-making. Member governments also receive support for framing national youth policies. The CYP is anchored in the belief that young people are a force for peace, democracy, equality and good governance. It also believes that the youth are a catalyst for global consensus-building and an essential resource for sustainable development and poverty eradication.[71]

The CYP has also been involved in the setting up of networks such as the Commonwealth Youth for Sustainable Urbanisation and the Commonwealth Children and Youth Disability Network—both of which aim to effect change by enabling youth through cross-country collaborations. One of CYP’s four centres was opened in Chandigarh, India in 1975 in collaboration with the Ministry of Youth Affairs, Government of India. Unfortunately, the centre was shut down in 2014 by the CYP’s London-based secretariat for reasons of “reorganisation” and “drain on resources”.[72] More recently, the Ministry of Youth Affairs has again collaborated with the CYP to set up programmes targeting at-risk youths.[73]

As discussed earlier in this analysis, development in education policy is an effective tool to improve a country’s human capital performance. The Commonwealth of Learning (COL),[74] founded in 1987, aims to improve access to learning opportunities by leveraging the benefits of distance learning. COL acts as a capacity builder by tapping into both formal and informal institutions to ensure that people are able to gain lifelong learning opportunities, thus advancing the SDG 4 target of quality education. The first decade concentrated on creating similar distance learning networks. With the adoption of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGS) in 2000, COL realigned itself to include teacher training and informal skill learning programmes that were focused on improving livelihoods in the target nations.

In recent years, COL has advocated for integration of technology to improve the efficacy of knowledge and skills. During the pandemic, COL committed to using online networks when education shifted online.[75] In India, a partnership was forged with the Sambhav Foundation in 2020, as part of which more than 2,000 workers were reskilled to become eligible for sanitation and hygiene entrepreneurship. COL also provided support by validating training content while standards were established for necessary certification.[76]

A similar organisation is the Virtual University for Small States of the Commonwealth (VUSSC)[77] established in 2006 through collaborations between education ministries of the Commonwealth Heads of Government, and efforts of COL. A network of educators who work on development and education solutions, its goal is to help at least 25 of the smallest nations in the world by improving access to education, laying down standards for qualification, better career advancement and enhancing human and institutional capacities. While over 258 million children were out of school in 2019,[78] the pandemic worsened the crisis. COL’s extended project aims to improve the situation in the Commonwealth by working for equitable and accessible education.

Its wing for advancing health rights, the Commonwealth Youth Health Network (CYHN), has helped countries work towards SDG 3 (good health and well-being) since its inception in 2016.[79] It focuses on the particular needs of youth and adolescents, and calls attention to people from small nations and those belonging to indigenous populations. The network has organised programmes that improved the provision of youth-friendly health services in India and Bangladesh, and mental health awareness initiatives in the Caribbean. It has also launched a programme called A4HPV,[80] which aims to eradicate cervical cancer in women by 2030.

Conclusion

This paper has six contentions. First, given the presence of a large young population in the Commonwealth, the youth capital needs to be actively incorporated in the global developmental paradigm. The focus on youth development must involve tracking of various youth-centric domains such as education, livelihoods, health, inclusion, equality, and peace and security, in order to bridge the progress gaps between the global North and South. Second, it is important to note that the youth play one of the most important roles in catalysing the SDG objectives in the areas of participation in policy designs and implementation of policies at the grassroots. The physical and human resource base in the Commonwealth nations must act as an enabler for the 2030 Agenda. The relationship between holistic youth well-being, as envisioned under SDG 3, and its contribution towards societal development must be recognised.

Third, the COVID-19 pandemic has amplified the disproportionate economic and societal vulnerabilities of the developing and underdeveloped world. Therefore, leveraging the youth capital for efficient use of demographic dividends, technology penetration, building global partnerships, and advancing climate action must be the way forward for building resilient societies among the Commonwealth nations. Fourth, investments in education and health must be a priority for the Commonwealth to augment the human capital base in the domestic economies. Focus must be aligned to youth-related spheres such as encouraging digital skilling and addressing mental health issues for increasing youth capital productivity and economic progress in the longer run.

Fifth, the youth need protection from the present-day ills of financial and gender inequalities, lack of livelihood opportunities, armed conflict, and substance abuse in order to contribute to a sustainable development model. Finally, the Commonwealth’s youth programmes and networks should be rebooted in the post-pandemic era and cover more expansive issues and domains.

While acknowledging the benefits of investing in youth for boosting human capital, the Commonwealth nations must also emphasise the importance of youth well-being as a goal in itself. While an empowered youth population can contribute to achieving the SDGs, many of these goals have targets that are focused on the youths themselves. This means that the youth are not only beneficiaries of the development agenda; rather, societies must invest in their well-being for effective human capital advancement for the long term.

Productive capabilities of the youth capital could provide a safety net to the economy in case of external macroeconomic shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic or the ongoing Ukraine-Russia war. Better coordination and cooperation between developed and developing countries in the Commonwealth forum should lead to upgrades in science, technology and other infrastructural capacities which can be effectively driven by the young population. The proactive stimulation of domestic and foreign investments in ensuring better demographic dividends, education, and health can go a long way in making economies more resilient.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Youth Development Index 2020 Scores and Ranks for the Commonwealth Nations

Source: Global Youth Development Report 2020, The Commonwealth[81]

Appendix 2: Domains of Well-being

Source: Ross et al. (2020), “Adolescent Well-Being: A Definition and Conceptual Framework”[82]

Appendix 3: New Work Opportunities based on Technological Advancements

Source: Global Youth Development Report 2020, The Commonwealth[83]

Endnotes

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV