The Sustainable Development Agenda is pivotal to the post-pandemic economic recovery process — and in the overall objective of creating a fair, equitable and sustainable world. This brief underlines two contentions: First, the SDGs contain various forms of capital — human, physical, natural and social — that are beneficial for governments and businesses, and a renewed policy focus on the goals will boost the post-pandemic global economy. Second, statistical evidence confirms a strong causal relationship between SDGs and the local business environment, and the SDGs will have long-term positive implications in the post-pandemic global economic scenario. It is crucial, however, that these results are treated as indicative and not more, given limitations in data availability.[d]

Nevertheless, the analysis indicates directions and provides the basis for an objective instrument of decision-making by attempting to reconcile the trinity of equity, efficiency and sustainability. This is perhaps the most significant policy challenge in the developing world.[43]

The exercise to establish the SDG index’s strong positive causality on the EDB scores has two significant policy implications. First, it will help arrive at a more holistic policymaking approach than the growth-focused ones, especially in developing countries like India. South Asian policymaking’s growth-fetishism has been associated with immense negative social and environmental externalities that often extract long-term costs and have been a key impediment to comprehensive growth and development aspirations.[44] The establishment of SDG causality on the business climate attempts to correct that by accommodating various capitals and preparing the economies measured to absorb or adapt to possible shocks, including those evolving from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Second, given the SDG framework’s potential to enable a congenial business climate, this brief infers that a country’s development policy should not be divorced from its investment and business promotion strategy. This exercise presents a business case for SDGs globally, which is missing from current policy thinking.

Policymakers must not lose sight of the challenges in implementing the SDGs, which predate the current crisis. The SDGs should not be seen as a measure of development alone, but also an important instrument to reflect the business environment. Crucial challenges to the 2030 Agenda include a rough start to the ‘decade of action’ (which could further delay the 2030 deadline that global institutions sought to meet), scepticism coupled with the difficulty in achieving goals, and a widening resource gap. Governments and other international players must come together with renewed political will and engagement.

About the Author

Soumya Bhowmick is a Junior Fellow at ORF, Kolkata.

Appendices

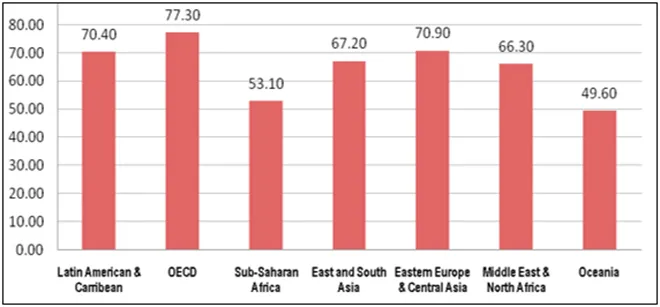

Appendix 1: World Regions’ SDG Scores 2020 (out of 100)

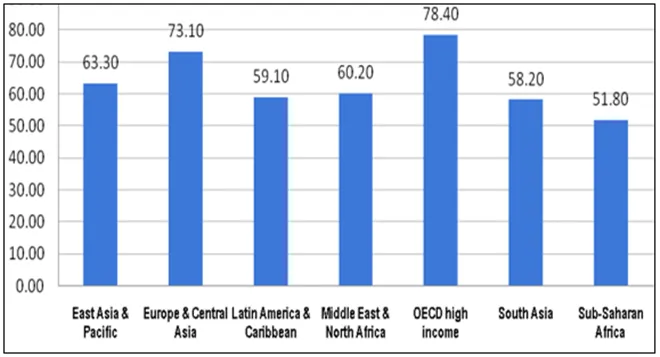

Appendix 2: World Regions’ EDB Scores 2020 (out of 100)

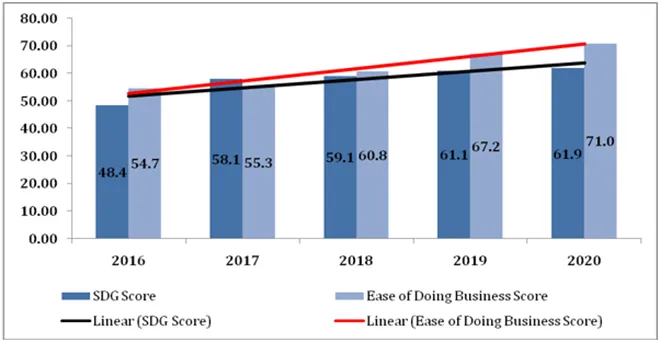

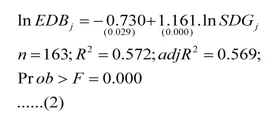

Appendix 3: Regression of ln EDB on ln SDG

| SUMMARY OUTPUT | ||||||||

| Regression Statistics | ||||||||

| Multiple R | 0.756 | |||||||

| R Square | 0.572 | |||||||

| Adj R Square | 0.569 | |||||||

| Standard Error | 0.160 | |||||||

| Observations | 163.000 | |||||||

| ANOVA | ||||||||

| df | SS | MS | F | Significance F | ||||

| Regression | 1.000 | 5.518 | 5.518 | 215.220 | 0.000 | |||

| Residual | 161.000 | 4.128 | 0.026 | |||||

| Total | 162.000 | 9.646 | ||||||

| Coefficients | Standard Error | t Stat | P-value | Lower 95% | Upper 95% | Lower 99.0% | Upper 99.0% | |

| Intercept | -0.730 | 0.332 | -2.200 | 0.029 | -1.385 | -0.075 | -1.595 | 0.135 |

| X Variable 1 | 1.161 | 0.079 | 14.670 | 0.000 | 1.005 | 1.317 | 0.955 | 1.367 |

Source: Performed in MS Excel

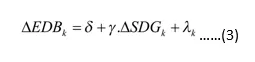

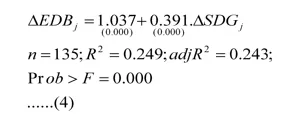

Appendix 4: Regression of ΔEDB on ΔSDG

| SUMMARY OUTPUT | ||||||||

| Regression Statistics | ||||||||

| Multiple R | 0.499 | |||||||

| R Square | 0.249 | |||||||

| Adj R Square | 0.243 | |||||||

| Standard Error | 1.674 | |||||||

| Observations | 135.000 | |||||||

| ANOVA | ||||||||

| df | SS | MS | F | Significance F | ||||

| Regression | 1.000 | 123.630 | 123.630 | 44.103 | 0.000 | |||

| Residual | 133.000 | 372.825 | 2.803 | |||||

| Total | 134.000 | 496.454 | ||||||

| Coefficients | Standard Error | t Stat | P-value | Lower 95% | Upper 95% | Lower 99.0% | Upper 99.0% | |

| Intercept | 1.037 | 0.189 | 5.502 | 0.000 | 0.664 | 1.410 | 0.545 | 1.530 |

| X Variable 1 | 0.391 | 0.059 | 6.641 | 0.000 | 0.275 | 0.508 | 0.237 | 0.546 |

Source: Performed in MS Excel

Endnotes

[a] Input market/factor market is a market in which businesses buy the resources or factors of production required to produce the good and services (products), which are then traded in the output/product market.

[b] Using the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network Index and the Ease of Doing Business Index.

[c] The World Bank’s EDB covers 12 areas of business regulation—starting a business, dealing with construction permits, getting electricity, registering property, getting credit, protecting minority investors, paying taxes, trading across borders, enforcing contracts, resolving insolvency, regulation on employing workers and contracting with the government. The last two parameters are not included in the EDB scores.

[d] Since its inception in 2003, the EDB Index has drawn criticism for failing to capture a holistic picture of a country’s business environment (for instance, it does not account for political environment). Yet despite this criticism, most of the missing elements are often extremely difficult to quantify. Moreover, the EDB index is the only such kind of global database on world economies.

[1] Nilanjan Ghosh, Soumya Bhowmick, Roshan Saha, “SDG Index and ease of doing business in India: A sub-national study,” Observer Research Foundation, June 17, 2019, https://www.orfonline.org/research/sdg-index-and-ease-of-doing-business-in-india-a-sub-national-study-52066/

[2] “Bangladesh: Strengthening Women’s Ability For Productive New Opportunities (SWAPNO),” SDGF, https://www.sdgfund.org/case-study/bangladesh-strengthening-women%E2%80%99s-ability-productive-new-opportunities-swapno%E2%80%8B

[3] “Bolivia: Improving the Nutritional Status of Children via the Strengthening of Local Production Systems,” SDGF, https://www.sdgfund.org/case-study/bolivia-improving-nutritional-status-children-strengthening-local-production-systems

[4] “Investment solutions for global impact,” SDG Impact, https://sdgimpact.undp.org/

[5] “Financial Sector Hub,” UNDP, https://v2.sdgfin.org/

[6] “Better Data, Better Decisions, Better Lives,” Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data, http://www.data4sdgs.org/

[7] “Why COVID has made SDG ambition more urgent than ever,” United Nations Global Compact, https://unglobalcompact.org/take-action/20th-anniversary-campaign/why-covid-has-made-sdg-ambition-more-urgent-than-ever

[8] “Make it your business: Engaging with the Sustainable Development Goals,” PWC, 2015, https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/sustainability/SDG/SDG%20Research_FINAL.pdf

[9] Ghosh, Bhowmick and Saha, “SDG Index”

[10] Jose Antonio Ocampo, “Reforming the international monetary and financial architecture,” Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, 2014, http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/iez/global/10900.pdf

[11] Christopher Carrollet. al., “The Distribution of Wealth and the Marginal Propensity to Consume,” Quantitative Economics 8, No. 3(November 2017): 977-1020

[12] Paul Geroski, Stephen Machin, “Innovation, profitability and growth over the business cycle,” Empirica 20, (1993): 35-50

[13] Jayati Ghosh, “Gendered Labor Markets and Capitalist Accumulation,” The Japanese Political Economy 44, no. 1-4 (2018): 25-41.

[14] Maelan Le Goff, “Feminization of migration and trends in remittances,” IZA World of Labour 220, (January 2016), https://wol.iza.org/uploads/articles/220/pdfs/feminization-of-migration-and-trends-in-remittances.pdf?v=1

[15] Gaelle Ferrant, Alexandre Kolev, “Does gender discrimination in social institutions matter for long-term growth?: Cross-country evidence,” OECD Development Centre Working Papers, No. 330, OECD Publishing, Paris (2016)

[16] David Cuberes and Marc Teignier, “Aggregate Effects of Gender Gaps in the Labor Market: A Quantitative Estimate,”Journal of Human Capital 10, no 1 (2016):1-32

[17] Nilanjan Ghosh, Soumya Bhowmick and Roshan Saha , “A ‘social’ index for Ease of Doing Business,” The Hindu Business Line, May 28, 2019, https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/a-social-index-for-ease-of-doing-business/article27277734.ece

[18] “The guide for business action on the SDGs,” SDG Compass, developed by GRI, UN Global Compact and WBCSD, https://sdgcompass.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/019104_SDG_Compass_Guide_2015.pdf

[19] “New Report: The Sustainable Development Goals and COVID-19,” GBC Health, July 2020, http://gbchealth.org/new-report-the-sustainable-development-goals-and-covid-19/

[20] William Easterly, “The Trouble with the Sustainable Development Goals,” Current History 114, No. 775 (2015): 322–324

[21] Mans Nilsson, Asa Persson, “Can Earth system interactions be governed? Governance functions for linking climate change mitigation with land use, freshwater and biodiversity protection,” Ecological Economics, 75 (2012): 61–71, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257342614_Can_Earth_system_interactions_be_governed_Governance_functions_for_linking_climate_change_mitigation_with_land_use_freshwater_and_biodiversity_protection

[22] Viktoria Spaiser et. al., “The Sustainable Development Oxymoron: Quantifying and Modelling the Incompatibility of Sustainable Development Goals,” International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 24, No. 6, (September 2016): 457-470,https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13504509.2016.1235624

[23] Erna Solberg, Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo, “Why we cannot lose sight of the Sustainable Development Goals during coronavirus,”World Economic Forum, April 23, 2020, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/coronavirus-pandemic-effect-sdg-un-progress/

[24] “Better Business Better World,” Business and Sustainable Development Commission, http://report.businesscommission.org/uploads/BetterBiz-BetterWorld_170215_012417.pdf

[25] “How are the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) influencing responsible investment?,” Greenstone, June 20, 2019, https://www.greenstoneplus.com/blog/how-are-the-sustainable-development-goals-sdgs-influencing-responsible-investment

[26] Nilanjan Ghosh, “How Covid-19 will affect sustainability and the UNSDGs”,dailyO,April1, 2020, https://www.dailyo.in/variety/covid-19-coronavirus-pandemic-un-sustainable-development-goals-sdg-health-climate-change-inequality/story/1/32643.html

[27] “COVID-19: Four Sustainable Development Goals that help future-proof global recovery,” UNEP, May 26, 2020, https://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/story/covid-19-four-sustainable-development-goals-help-future-proof-global

[28] Ghosh, Bhowmick and Saha, “SDG Index”

[29] Robert Ayres et. al. “Natural Capital, Human-made Capital, Economic Growth and Sustainability,”Boston University (1996): 15-16.

[30] Mohan Munasinghe, W. Reid, “The Role of Ecosystems in Sustainable Development,” Biodiversity and Quality of Life, ed. N. Sengupta and J. Bandyopadhyay (New Delhi: Macmillan, 2005)

[31] Munasinghe and Reid, “The Role of Ecosystems”

[32] Alex Ryan, “What is Systemic Design?” The Overlap, February 3, 2016, https://medium.com/the-overlap/what-is-systemic-design-f1cb07d3d837

[33] Soumya Bhowmick, “COVID-19 ‘infecting’ Sustainable Development Goals,”AsiaTimes, April 29 ,2020, https://asiatimes.com/2020/04/covid-19-infecting-sustainable-development-goals/

[34] “Sustainable Development Goals,” United Nations, https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/

[35] Ghosh, Bhowmick and Saha, “A ‘social’ index”

[36] International Peace Institute, SDG Fund, and Concordia, “A New Way of Doing Business: Partnering for Peace and

Sustainable Development,” International Peace Institute (New York: September 2017), https://www.peacewomen.org/sites/default/files/IPI-Rpt-New-Way-of-Doing-Business.pdf

[37] “Doing Business 2020,” The World Bank, https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/reports/global-reports/doing-business-2020

[38] “Sustainable Development Report 2020,” Sustainable Development Solution Network, https://www.sdgindex.org/reports/

[39] “Sustainable Development Report 2020,”SDSN

[40] “Doing Business 2020,” The World Bank,

[41] “Kolmogorov-Smirnov Goodness-of-Fit Test,” Engineering Statistics.

[42] “Doing Business 2017,” The World Bank

[43] Ghosh, Bhowmick and Saha, “SDG Index”

[44] Nilanjan Ghosh, “Promoting a ‘GDP of the Poor’: The imperative of integrating ecosystems valuation in development policy,” Observer Research Foundation, March 17, 2020.

[45] “Sustainable Development Report 2020,”SDSN

[46] “Doing Business 2020,” The World Bank

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV