Introduction

The IS Khorasan (IS-K) is the Islamic State’s offshoot in Afghanistan’s complex landscape of insurgencies, terrorism, and political and tribal crevasses. First seen in 2015, its visibility has steadily increased over the past few years, conducting (or claiming responsibility for) attacks conducted in and around the capital city of Kabul.

Current narratives around IS-K are convoluted, with the group having a mixture of members of former insurgent groups not only in Afghanistan, but in Pakistan as well. The relative rise of IS-K comes at a time when Afghanistan is embarking on a long process of reconciliation and potential peace with the Taliban, as the US plans its military withdrawal.[a]

The IS-K threat—set against the peace negotiations between the Taliban, the Afghan government, and the US—is a fulcrum moment not just for Afghanistan, but for South Asian security in general. Indeed, along a wide swathe of corridor that stretches from the Iran–Afghan border all the way to Kashmir, insurgency has thrived, with and without state assistance. Insurgent and terror groups that flourish without the state are the ones that apply themselves both strategically and tactically to navigate political and military grey areas. As for IS-K, it is difficult to study its patterns and hierarchies, and even more to decipher available information in order to form a concrete understanding of its security implications for the wider South Asian region.

IS-K today arguably is the most visceral ISIS wilayat (an administrative division), with capabilities of orchestrating some of the most violent attacks in the country across the civilian and governmental spectrum.[1] The brand’s increasing potency in parts of Africa, and its implications on South Asian security, require a closer look into the developing situations in the Afghanistan–Pakistan region and its extensions into South Asia as a whole. Other related issues that need to be examined are the absence of a framework for dealing with returning fighters (both legally and politically), and the poor state of cooperation on counterterrorism between South Asian states, despite the forum afforded by SAARC (South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation). These weaknesses point to an overall lack of an ecosystem where terrorism in the region can be debated, and for which sustainable solutions can be found.

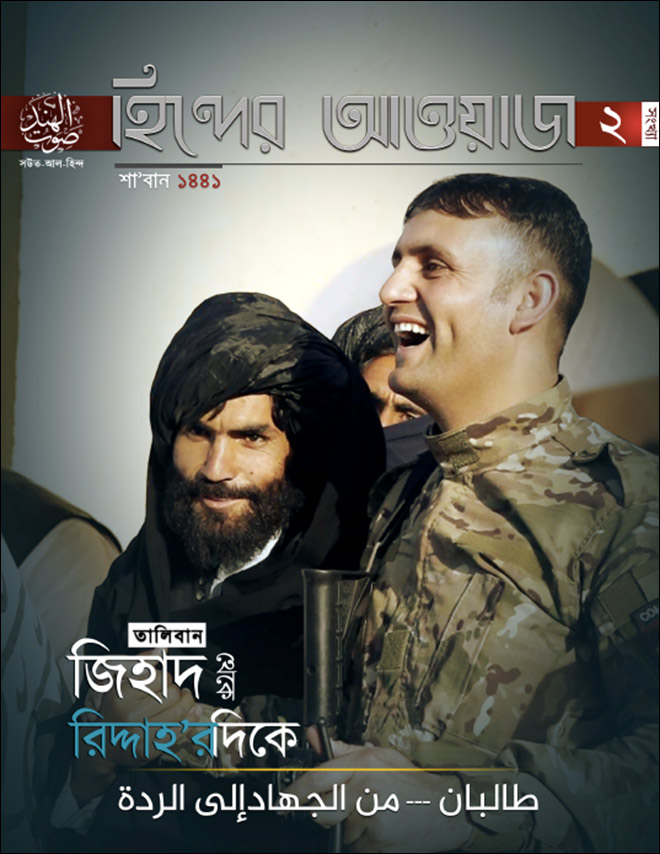

IS-K, Taliban, and Implications for South Asia

The global terrorism landscape is a fast moving one. Often in the recent past, terror groups have managed to gain the upper hand in both strategy and tactical operations, making sure to not only safeguard their own existence, but in many cases force states and the global community to the negotiating table. Terrorists’ tools have evolved faster than their state adversaries, as they adapt to new technologies such as the internet, social media, and even crypto currency (as a method to move around finances). While scholars such as Dan Byman argue that over the years groups such as the Al-Qaeda have diminished in their strength, potency and impact, the threat perception remains consistent, and in some cases, even heightened in the aftermath of 9/11 and the US’ consequent ‘war on terror’.[2]

The IS-K is itself a kaleidoscope of groups and even state-backed support. While South Asia is not new to terrorism, a significant rise and plausible spillover of the IS-K ideology from Afghanistan to other countries of the region, could usher a new era. In India, pro-ISIS individuals generally consider the Kashmir conflict as being geographic—a fight over land by nationalists and patriots—and not necessarily in the name of Islam.[3] Such view could be altered as IS-K gains a foothold in Afghanistan, and spills over in Pakistan, Kashmir, and beyond: the ideological landscape could shift beyond just the Kashmir issue and become an all-encompassing cause of deeper sectarian fissures.[4]

The Afghanistan war could yet prove to be a watershed for the global push against terrorism. As the US’ negotiations with the Taliban intensified in 2018 to withdraw its military troops from the conflict, the Afghan case set the stage for the argument that outright military defeat of a terror, insurgent or armed non-state group—despite the overwhelming military power of the US—is not the final, concrete outcome that peacemakers are aiming for. The power imbalance is clear in that between 2006 and 2014, the US and its Western allies dropped 36,971 bombs via 16,541 strike sorties in Afghanistan, against an adversary that did not have any air power capacity.[5] Nonetheless, the final outcomes have been drastically different from what was expected both for the fields of international relations, and counterterrorism and counterinsurgency.

In February 2020, after intense negotiations amidst calls for great caution in dealing with the Afghan Taliban, the US and the Taliban signed an agreement in Doha, Qatar, to work towards bringing peace to the embattled country.[6],[b] The four-page agreement is only a preface to the end of America’s longest running war—a conclusion that is more palatable to the American people than Afghanistan.

IS-K, on the face of it and as part of the ISIS’ central design, is against the governments of both Afghanistan and Pakistan. However, strategic and tactical opportunism by local actors and regional states has made IS-K much more difficult to deconstruct. Between 2014 and 2017, the Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), Haqqani Network, Jamaat-ud-Dawa and the Afghan Taliban have on various occasions criticised the IS-K; others such as the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) and Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) within their own ranks had differed over IS-K. At the same time, in that period, all of these groups saw defections to IS-K from their own cadre.[7],[c] These defectors—disgruntled former commanders, even—were ideal for ISIS to co-opt: they had leadership aspirations in Afghanistan’s jihad landscape, and IS-K was their hope.[8]

Meanwhile, anonymous sources in India’s security establishment speaking around the US–Taliban deal suggest that groups such as LeT, Jaish-e-Mohammed, Afghan Taliban and Haqqani Network have joined hands to target Indian interests in Afghanistan. While the veracity of these reports remains in doubt, the narrative is a significant departure from existing notions of how IS-K relates with other groups in Afghanistan.[9] Scholar Anand Arni explains the relationship between the LeT and IS-K: “Pakistan’s attempts to prop up the ISK or to create a new entity which is essentially influenced by the LeT fits in with the long-held expectation that Pakistan will create a pressure group to (a) keep the Taliban in line with their interests if the peace deal works, (b) give the LeT an element of deniability in future operations which cannot be attributed to the Taliban or the Haqqani Network, (c) counter the militias equipped and funded by the CIA, and (d) provide military assistance to the Taliban. It is also to safeguard against the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM) becoming a militant movement and possibly give deniability to the ISI if they venture into training foreign (Indian) insurgents on Afghan soil[10].” Arni’s views give a glimpse of the multiple cogs of the Afghan jihad wheel that move simultaneously, catering to various domestic, regional and international interests.

To be sure, using IS-K as a tool of plausible deniability is not unique to South Asia; indeed, ISIS itself has used the tactic of claiming responsibility for attacks despite there being no clear proof that it had directly anything to do with them. ISIS claimed a hand, for instance, in the mass shooting in Las Vegas in October 2017 that killed 59 people.[11]

This paper reviews the development of IS-K’s influence in South Asia, both in its current capacity and the possibilities of the group being coopted further by regional actors for strategic gains. It looks at the possible connections between IS-K in Afghanistan and an increasing number of pro-ISIS online propaganda outlets on the internet targeting South Asian Muslims, and explores the kind of change IS-K could influence in arresting terrorism in South Asia.

IS-K and Indian Fighters: An Assessment

In issue number 246 of Al Naba,[12] a weekly magazine of the Islamic State (ISIS, or Daesh in Arabic), the front page was dedicated to the attackers of the August 2020 Jalalabad terror strike[13] in Afghanistan’s Nangarhar province, a known stronghold of IS-K. According to reports, the attack was conducted by more than 25 IS-K terrorists, which included three Indians, four Tajiks, and a Pakistani, giving it a truly South Asian construct.[14]

Afghanistan is at a crossroad, with the Taliban holding a stronger deck of cards than the US, as both parties negotiate the American military withdrawal after 19 years of conflict. The IS-K, meanwhile, has found itself in the midst of Taliban–US politics, with the outgoing Trump administration suggesting at times that the Taliban was a viable partner in fighting against IS-K. The US Central Command head, Gen. Frank McKenzie, has said that the US had already provided “very limited support” to the Taliban against the IS-K.[15] This not only gives IS-K a boost, but also makes it an attractive proposition for all those within the Taliban, and beyond, who do not agree with the group’s leadership to negotiate a resolution with the Americans.

The IS-K ‘program’ has been witnessing a slow yet steady and observable rise. The attackers of the Jalalabad prison video-recorded themselves in Urdu, and not Dari, Pashto or even Arabic. One of the three Indians who allegedly took part in the attack was reportedly a trained doctor, Ijas Kallukettiya Purayil, who was on India’s National Investigation Agency’s (NIA) most wanted list. According to the NIA, Purayil was part of a 22-member contingent of men and women from the southern Indian state of Kerala that left the state’s Kasargod district led by one Abdul Rashid Abdulla to join the IS in Afghanistan. Since 2016, reports have been emerging regularly about many members of this module dying in action there, including some in the American ‘Mother Of All Bombs’ (MOAB) strike in the country’s Nangarhar province in April 2017.[16] Some of the women of this group, widows of these ISIS fighters, still remain in prison in Afghanistan.[17]

In Al Naba, a picture of Purayil was featured on the front page with an article on the success of the attack and the martyrdom of the attackers which, as per the publication, led to the release of hundreds of people.[18] That the propaganda video was made in Urdu, while Purayil was from Kerala where the prevalent languages are Malayalam and English, raises questions over the design of IS-K, and the kind of outreach it may be seeking into the Indian sub-continent. Prior to the Jalalabad attack, IS-K also claimed the attack on a Sikh gurudwara (temple) in Kabul in March 2020, which killed more than 25 people. The attack was also allegedly conducted by an Indian ISIS member from Kerala, as per IS-K claims; another report contests this.[19]

While Urdu is widely spoken in Pakistan, it is not common in Kerala; it is though in northern India, specifically in states such as Uttar Pradesh (UP), home to more than 35 million Indian Muslims. UP is also the land of important Islamic institutions of South Asia such as the Barelvi movement and the Darul Uloom Deoband seminary, home of the Sunni Deobandi Islamic movement which has a following that stretches as far as Central Asia.[20] With UP’s neighbour states, Bihar and West Bengal, the three north Indian geographies have a 76-million-strong Muslim population that has remarkably deterred any attempted inroads by transnational Islamist groups such as Al-Qaeda and ISIS. However, that does not mean that the threat perception has been minimised or that groups will not succeed in the future. Researcher Mohammed Sinan Siyech has highlighted how little work has been conducted on transnational terror threats to India’s ‘hinterland’, underlining a large gap in security studies in the region.[21] For example, Siyech highlights, the Al Qaeda in Indian Subcontinent (AQIS) still actively refers to the “legacy” of Muslim kings that ruled the region for over 800 years in its propaganda and theological materials aimed at South Asia.[22]

There has been an observable increase in pro-ISIS cases in India being linked to IS-K, and not ISIS central. In August, two such cases came to light, with one alleged pro-ISIS operative being arrested in Delhi[23] and another in Bengaluru on charges of making mobile apps for the terror group.[24] Earlier in the year, a couple identified in the media as Jahanzeb Sami and Hinda Bashir Baig were arrested in Delhi on charges of running a pro-ISIS online ecosystem that incites protests against India’s contentious citizenship bill (which has also been the pivot of riots in the Indian capital during that same period).[d],[25]

Since the 2014–2017 period, anecdotal evidence, especially online, points to IS-K as having a stronger play in South Asia than ISIS central. While this was heightened with the death of ISIS chief Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in 2019, making wilayats such as IS-K along with its leadership more powerful and approachable regionally, the overall influence of the group remains at static levels if compared to the number of cases and/or arrests witnessed every year since 2014.

Another significant regional variable that works in favour of transnational jihadist groups such as ISIS is that there is hardly any regional mechanism in South Asia that recognises terror groups and acts on them from a cohesive South Asian perspective. Historically, the attempted mechanisms between South Asian capitals to develop joint regional debates, practices and policies to view groups such as ISIS and Al Qaeda have stalled due to the India–Pakistan dynamic.[26],[e] While Pakistan’s state-sponsored terrorism remains the nucleus of global Islamist terror debates, and not just in South Asia, that the rest of the region cannot synergise their counterterrorism efforts gives access to terror groups to build their ecosystems, now both online and offline.[f] This has precedence in the past.

Tailoring Propaganda for South Asia

South Asian states are characterised by ideological, theological and cultural fissures that exist within the same geographies. Analysts generally agree that this is why these countries have not been able to arrive at a singular, cohesive approach to terrorism. While South Asian states have worked together on counterterrorism via multilateral forums such as the UN,[27] few mechanisms exist on a bilateral and intra-regional level. Terror groups have taken advantage of these gaps, creating propaganda and narratives that have built a brand value that tends to overestimate their capabilities on the ground.[28]

In February 2020, a pro-ISIS online propaganda publication, Sawt-al-Hind (‘Voice of Hind’) was launched by an online entity called Al-Qitaal Media Center. The launch coincided with communal riots that were taking place in parts of the capital New Delhi at the time, with the cover also featuring images of the same.[29] Over subsequent issues, the publication started to release translated excerpts in Urdu, Hindi and Bengali—all languages most commonly spoken among the north Indian Muslim populations. Although the Hindi translation uses the Devanagari script, and not necessarily Hindi words and terms—as spoken Hindi in northern India takes many words from Urdu and Persian—such concoction of script and language serves to extend the reach of these texts. It showcases a strategic and tactical move to develop propaganda for a specific cultural and geographic demography within the Indian landscape. While many pro-ISIS related cases of radicalisation have come from the southern state of Kerala—which has historic ties with the Gulf and has over 2 million of its citizens working in Saudi Arabia, UAE, Bahrain and other neighbouring states—cases from northern Indian states have been far and few.[30]

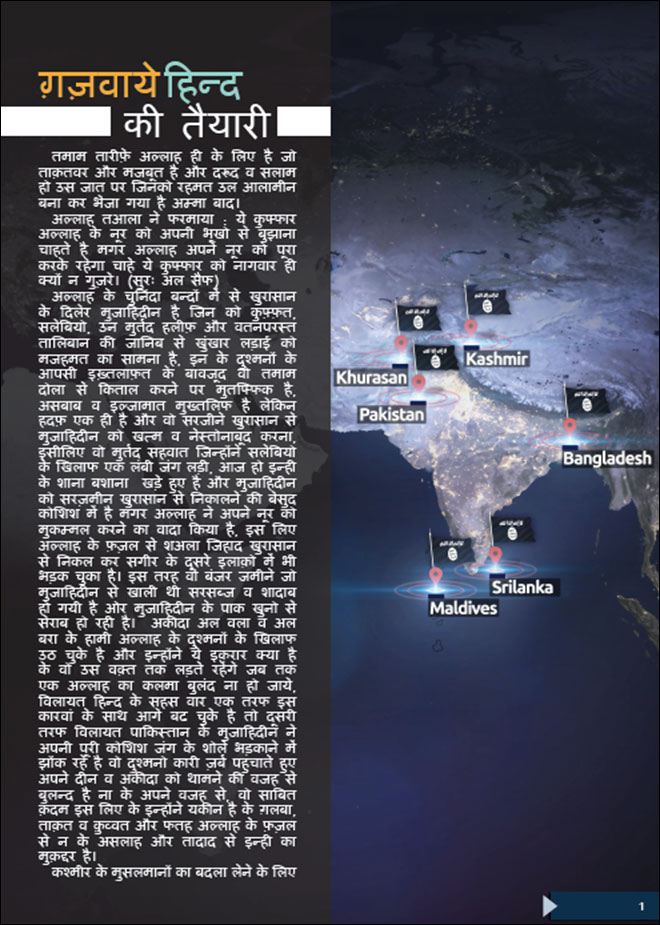

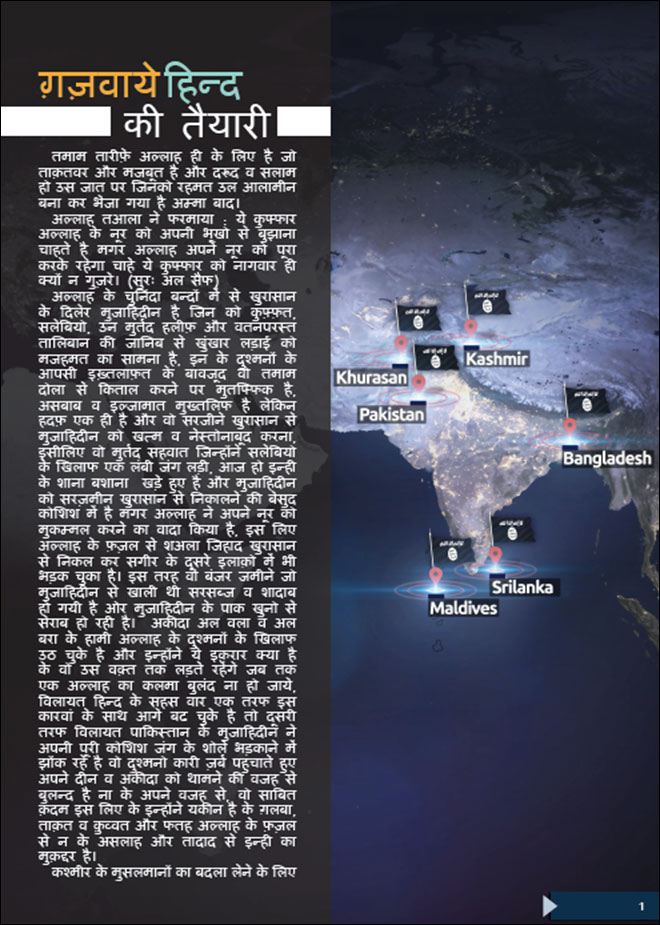

Fig. 1: An example of a Hindi translation of a Sawt-al-Hind issue[31]

Issue Number 7 (released in August 2020) of Sawt-al-Hind had an interesting construct of ISIS’ vision of being a “global entity” while also maintaining a strong regional outreach. The front page of the issue shows an ISIS fighter, holding the IS flag, standing on a road leading to Babri Masjid (Mosque) in Ayodhya, India, where a long-standing dispute between the Indian Hindu and Muslim communities over the mosque and an erstwhile historic temple on the same piece of land was brought to a conclusion by the Supreme Court.[32] That judicial decision allowed the Hindus to re-build a temple at the site of the mosque which was demolished by rioters in 1992.

The other imagery used on the cover was that of the Al-Aqsa mosque, Islam’s third holiest site, in the contested historic city of Jerusalem, Israel. As part of the August 2020 normalisation deal between Israel and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the keys of the Al-Aqsa mosque were given to Israel, angering Palestinians and other stakeholders in the Arab world. This Sawt-al-Hind cover showed that even in India, where the numbers of pro-ISIS cases remained minuscule—both domestic terrorism and those who wished to or succeeded to travel and join the Islamic State in Syria, Iraq or Afghanistan—the group continues to construct divisions within the social fabric from the point of view of a larger fight for the Islamic ummah. The number of Muslims living in India is over 200 million, and the number of pro-ISIS cases stand anywhere between 180 – 200[33] (the last official figure from the Indian government side was reported to be 155 as of June 2019[34]). Meanwhile, a country such as Belgium, where Muslims make up a mere 7.6 percent of the total population[35] of around 11.6 million people, has had over 400 cases of people travelling to Syria and Iraq to join and fight for ISIS.[36]

However, one of the first known Indians to establish himself within the IS-K ecosystem was in fact, from UP. Shafi Armar, former Indian Mujahideen, a now defunct terror group in India, created the group Junood-ul-Khalifa-e-Hind (JKH) in an attempt to set up a new, pro-ISIS aligned entity in 2015. Eventually, Armar made it to Afghanistan, and became ‘Yusuf al-Hindi’, a moniker that still remains in use even after his death.[g] Armar’s attempts in India were also not region-based, but relied more on ecosystems online; identity, beyond Islam, was irrelevant. Nonetheless, pro-ISIS cases both in northern India, and even in Kashmir, remained minimal despite open-source data[h] suggesting that the number of militants killed in the Kashmir Valley who had self-declared affiliations to ISIS has increased over the past year. The increase in IS-K-related South Asia movements comes at a time when the Taliban–US deal stands at a precarious juncture, as the new US administration prepares to take the helm in January and neither the US and Taliban, nor the Afghan government led by President Ashraf Ghani, have a plan B.[37] This gives IS-K a degree of attractiveness for some regional players to coopt as a leverage against both the US and the Taliban, and influence the direction a post-US Afghanistan would take.

To the east, a subtle push once again towards Bangladesh is also visible. Sawt-al-Hind’s translations into Bengali highlight the evolving strategies of the group in its post-caliphate avatars. In IS’ erstwhile publication, Dabiq (later renamed Rumiyah), West Bengal featured heavily with earlier issues highlighting propaganda for a sustained ISIS presence amongst the Bengali population. For example, issue number 12 of Dabiq had a long feature, ‘The Revival of Jihad in Bengal with the Spread of the Light of the Khalifah’ in November 2015,[38] during the peak of the Islamic State’s ideological and territorial gains. It was around the same time that Bangladesh witnessed a spate of knife and machete attacks on writers and activists advocating secularism in the Islamic country.[39]

Between April and October, small-scale pro-ISIS attacks in Bangladesh have occurred at regular intervals, and local political parties have often sparred over the presence of the group and its influence in the country.[40] Scholar Saimun Parvez highlights that Bangladesh faces significant security gaps by not offering clear information and intelligence on the roots of ISIS in the country, this being played on by local political parties for domestic gains as well. In August 2019, following the arrest of pro-ISIS youths in the capital Dhaka, ISIS’ Amaq News released another video in which Bengali ISIS members threatened to conduct attacks in the country on foreigners, politicians and minorities.[41]

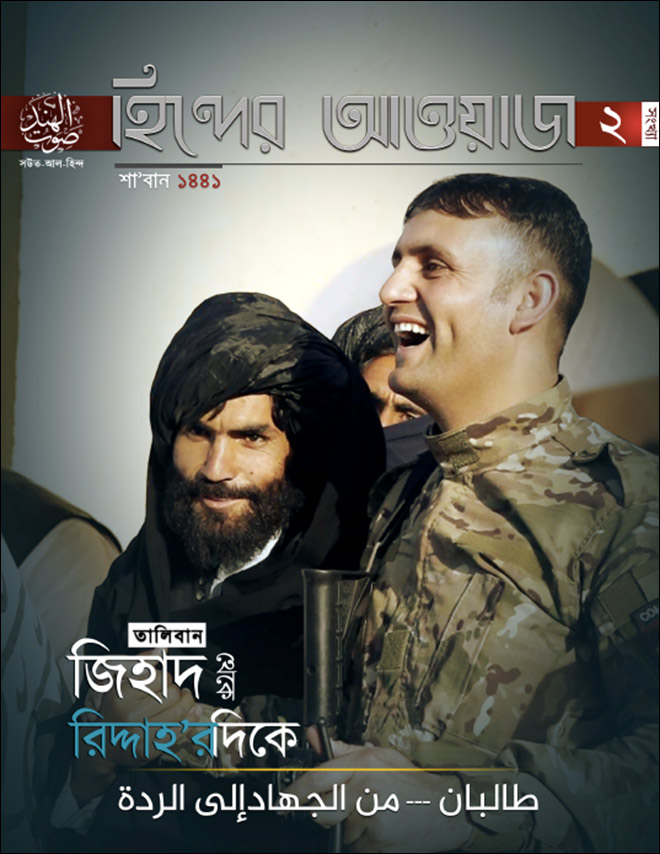

Fig. 2: Cover of a Sawt-al-Hind issue translated into Bengali[42]

In the initial stages of ISIS’ outreach in South Asia, the role played by dedicated individuals in creating ecosystems was undervalued. For example, Canadian–Bangladeshi Tamim Ahmed Chowdhury, known by his kunya (IS pseudonym) Abu Ibrahim al-Hanif and who may have travelled to Syria in 2012–2013, had masterminded Bangladesh’s largest ISIS-claimed attack—the July 2016 killings at the Holey Artisan Bakery in Dhaka.[43] The Sawt-al-Hind is multi-lingual, keeping in mind South Asia’s diversity, revealing a more intricate yet focused approach for propaganda dissemination targeting the region’s Muslim population. This was previously not seen as a direct opportunity for transnational Islamist groups. Scholars Carol Winkler, Kareem El-Damanhoury, Zainab Saleh, John Hendry and Nagham El-Karhili, in their seminal research on ISIS leadership losses and their effects on propaganda output, found that loss of ISIS leadership figures working on issues such as media propaganda led to a “significant” observable difference, whether qualitatively or quantitatively, over the long term.[44],[i]

Much like IS-K’s own constitution—of ideologies and fighters coming from a broad spectrum of backgrounds—its propaganda is also multifaceted. In April–May 2020, a ‘special issue’ of Sawt-al-Hind came out on the group’s Telegram channels. The theme was the lockdown, initiated across the world due to the Covid-19 pandemic, and communal violence in India during the same period—the magazine tied the two together to create a narrative for Muslims in countries such as India to rise against the state.[45] The communal violence was discussed in the issue in a way that depicted secularism and democracy as anti-Islam; the coming of the pandemic, meanwhile, was a sign from God to correct erroneous ways that some Muslims have embraced, such as democratic systems.

Sawt-al-Hind itself would soon claim that the issue was “fake”.[j] It is not known whether Sawt-al-Hind is organised (directly or indirectly) by online ecosystems close to IS-K or ISIS (or even disruptive narratives pushed by design by entities such as the ISI itself). What is clear is that the push for narratives in a region such as South Asia is not a wholesome game, even if IS-K is attempting to assert itself in the entire Khorasan region. The possibility of divisions between pro-ISIS facilitators from different Islamic backgrounds within South Asia, ranging from Pakistan to India and Bangladesh to Maldives, remains fluid.[46]

The Afghanistan – Pakistan Corridor

The Afghanistan-Pakistan corridor is the geography of IS-K’s birth. Where Pakistan comes into play will not only been critical to the success of the Taliban–US negotiations but will be crucial in the kind of peace that the Afghans will inherit, if at all. The arrest of Pakistani militant and IS-K leader Munib Mohammed,[47] known to be a bridge between the IS-K and Pakistan’s intelligence apparatus, highlights the multiple avenues that Pakistan has operationalised to make sure that a post-US Afghanistan is not anti-Pakistan Afghanistan. While Pakistan made inroads into IS-K a few years ago,[48] the Haqqani Network has also activated relations with IS-K on a number of fronts, including conducting attacks on Kabul, and often, aligning with Pakistan against the interests of both the Afghan government and the international community. Adding to the picture is an increasingly reinvigorated Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP),[49] whose cadre created the first IS-K ecosystem after being pushed across the Durand Line into Afghanistan by Pakistani military primarily during Operation Zarb-e-Azb which lasted between 2014 and 2016.

Indeed, the IS-K ecosystem remains divided, and run largely by non-Afghan affiliates, including those who at least previously stood against Pakistan’s interference into the group’s financing.[50] Scholars Sean Withington and Hussain Ehsani in their research have highlighted that groups such as the TTP, Ansur-ul-Mujahideen and the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) have held close relations with Pakistan’s ISI, adding further dimensions to stories about the arrest of Pakistani spies in Afghanistan’s Nangarhar province while trying to coordinate plans and supplies with IS-K.[51] This, despite analysis that suggests entities such as the IMU have weakened in Afghanistan over the past few years, making them ideal examples of the kind of jihadist groups that would look to align or merge with a larger entity such as IS-K to further their own validity and safety.[52]

The challenge of deciphering the IS-K is a difficult one in itself, particularly from the point of view of leadership and hierarchy, as well as its operational relationships with other groups. It is important to remember that Taliban, Al Qaeda and IS-K are only three of the many groups operating in Afghanistan’s jihadist ecosystem. More than 20 terror groups, most of them from Pakistan, hold control on these spaces. For example, in 2017, Afghanistan identified LeT, Jaish-e-Mohammed, TTP as supporters of the Taliban, while lesser known groups such as Shura-i-Etehad Mujahidin and Maulvi Nazir Group were found to have training camps in Waziristan for conducting attacks across the Durand Line.[53]

To be sure, Pakistan-based groups constitute a large section of IS-K fighting cadre. They continue to rely on Pakistan’s intelligence infrastructure for strategic and tactical support, to safeguard themselves against the Afghan military, the Pakistan military in its tribal belts, and local warlords. This gives the Pakistan state access to a deeply ingrained terror system that it is able to manipulate according to its own geo-political requirements.

The playbook of IS-K’s development and ecosystem are not only of interest to Afghanistan, but equally, if not more, to India. IS-K’s perpetrated leadership has suffered significant and consistent losses over the years. Like other groups, IS-K also benefits from ecosystems that sustain themselves, financially and politically, by continuously prolonging the Afghan conflict and actively working to subvert peace processes, including the US–Taliban negotiations and eventually, the intra-Afghan dialogue as well. In their research on IS-K leadership losses between 2015 and 2018, scholars Amira Jadoon and Andrew Mines note that 399 individuals from various seniority levels within IS-K were either killed or captured, or else surrendered during this period, with 2017 being the peak year of casualties suffered by the group amidst an expansive US-led air campaign.[54] Jadoon and Mines coded IS-K’s leadership into four tiers, ranging from Emirs at the top to mid-level and local leaders. In both Afghanistan and Pakistan, the largest losses were observed, expectedly, in the local tiers while the former also saw the killings of four Emir-level leaders (or their equivalent). The local tiers, while suffering losses, are also the easiest to replace.

Ensuing debates over the ‘ownership’ of IS-Khorasan have also offered interesting insights over a possible tussle between Pakistan-backed groups. These groups will want to make sure that they retain control of the brand, and any attempt for ISIS central to stake claim over the said leadership could become detrimental to attempts to factionalise and control parts of this ecosystem. In the still-vibrant online space of pro-ISIS propagandists, a day-long debate played out over the identity of the alleged new leader of IS-K.[k]

According to open-source reports, the new IS-K chief is identified as one Dr. Shahab al-Muhajir, appointed around May and June of 2020.[55] Previously, UN monitoring reports have suggested that the new IS-K chief could be from Iraq or Syria—which would be a first. Obtaining consistent and steadfast clarity of information over the leadership of IS-K is an important task for the multiple stakeholders in Afghanistan’s complex counter-terror ecosystem. IS-K’s story has ebbed and flowed: it suffered heavy losses in 2017, regained strength in 2018, and once again experienced losses in 2019.[56] Still, the group has seen an eight-fold increase in strength during the same period, with a reported increase of 5,000 fighters just between 2018 and 2019.[57]

While Muhajir’s identity is still debated, researcher Abdul Sayed has observed that IS-K’s media outlet, al-Milat Media, aired an audio message written by Muhajir, but read out and recorded by IS-K’s spokesperson Sultan Aziz Azzam in Pashto, and not Muhajir himself. Sayed says this could signal that Muhajir is not fluent in local Afghan languages and dialects, hinting that he may not be from the region.[58] The counter-arguments on Muhajir’s identity is that he is from Pakistan, possibly former TTP, even though alleged pro-TTP accounts on social media believe that al-Muhajir is in fact Afghan, and his identity is kept secret due to security issues.[l] It is also important to note that after al-Baghdadi’s death, ISIS stated that its new chief was one Abu Ibrahim al-Hashemi al-Qurayshi, whose identity remains widely debated in public discourse, one year since the announcement.[59] On 3 September 2020, ISIS claimed an attack against the Taliban in Nangarhar—the first such attack against the Taliban since Muhajir allegedly took over the role of emir of the IS-K.

The coming few years will be critical for Afghanistan’s security systems, and by association, South Asia’s. The two biggest pro-ISIS terror strikes in the region—Dhaka, Bangladesh in 2016[60] and Sri Lanka in 2019—[61] were conducted in a fairly self-sustained manner as far as planning and execution is concerned. Although ISIS claimed the Sri Lanka attack,[62] there is still no proof whether the Sri Lankan attackers had any direct links with ISIS central in Syria or IS-K in Afghanistan.[63] Indeed, ISIS thrives in these gaps in information and operations, as it utilises ‘digital information guerilla warfare’ tactics which more than often today turn into offline narratives as well, sometimes even succeeding in sowing community discord.

As Afghanistan remains a concern, with its future hanging in the balance between Washington D.C. and the Taliban, the ISIS ecosystems in South Asia have started to resemble some sort of structure online. The fifth issue of Sawt-al-Hind, in a highly traditional ISIS propaganda style, dedicated three pages paying tribute to the online supporters of ISIS in South Asia. As far back as 2015, ISIS had published propaganda clips framing the rules of “information jihad”.[64] In 2016, the ISIS manual, ‘Media Operative, You Are A Mujahid, Too’ showed up on pro-ISIS channels on Telegram.[65] A cursory comparison between the manual, and the language of Sawt-al-Hind’s article on the same topic highlights linear patterns of propaganda, and a degree of commonality between ISIS’ main publications and the satellite one.

In August 2020, the Taliban made a visit to Pakistan led by Taliban’s political chief Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar—despite Islamabad sanctioning the group—to escape charges and sanctions as part of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) process. This shows the lucid manner in which international regulations and Pakistan’s web of various Islamist functionaries deployed on both sides of its borders work to leverage the state’s geo-political aims with limited international challenge.[66] There is no doubt that the Taliban would know Pakistan’s plays, considering almost all of the Taliban’s powerful shuras (consultative councils) are based in Pakistan. To put this in perspective—in mid-August 2020, the Pakistani government initiated sanctions against the Afghan Taliban to avoid defaulting on its commitments to the FATF, which could result in its economy being grey-listed.[67] However, the sanctions against the Taliban were unabashedly symbolic: top Taliban political leaders such as Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, who was also sanctioned, arrived in Pakistan only a few hours later with a full public reception.[68]

Comparatively, ISIS has not managed even a small presence within Pakistan. This reveals the strength of the ideological base of the Kashmir issue in the country, which Pakistan can manage within IS-K ranks as well to its advantage. While there have been occasional attacks claimed by ISIS in Pakistan, few have come towards any of the key cities. However, the argument of the Pakistani jihadist space being crowded predominantly by pro-Pakistan state and pro-Kashmir groups does not mean IS-K will be shunted out completely. In fact, Pakistan as part of its strategy is in a good position to fester IS-K in Afghanistan and publicise the Kashmir issue being that of a pan-Islamic ummah—this could see the likes of IS-K and LeT finding commonalities with one other.

From an Indian perspective, the fluidity of IS-K’s structures and the early access Pakistani fighters attained within the group make it ripe for being used, as an entire entity or parts of the entity, to target Indian interests both in Afghanistan and in Kashmir. The addition of recent political orientations of the state itself, with the ruling BJP’s ‘Hindu nationalist’ movement to both governance and society (an example seen through the lens of anti-CAA and NRC protests in New Delhi which led to violence) could also be seen as an opportunity for groups such as IS-K, that, once again, rely much more on the ideology of a battle for the larger cause of the ummah than the limitations of regional or geographical rivalries. These political gaps could be manipulated not only by the likes of IS-K, but by adversarial state-led ecosystems as well.[69] These narratives indeed call for a new approach to Indian counter-terror thinking, where the entire process is not reliant on kinetic actions and reactions.

Regions such as Nangarhar, which is attached to the porous Durand Line border between Afghanistan and Pakistan, are technically not a large enough geographical area. From this point of view, the territorial threat posed by IS-K could prove to be manageable from an Afghan perspective. At the same time, however, it may be easy to manipulate from a Pakistani perspective, from the Durand line up to the Line of Control in Kashmir. The imperative is to manage the battle of perceptions, ideas and narratives.

Conclusion

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV