-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

This brief is part of ORF’s series, ‘Emerging Themes in Indian Foreign Policy’. Find other research in the series here:

Shubhangi Pandey, “Exploring the Prospects for a Negotiated Political Settlement with the Taliban: Afghanistan’s Long Road to Peace”, ORF Issue Brief No. 279, February 2019, Observer Research Foundation.

Introduction

Afghanistan has been suffering one of the world’s deadliest insurgencies for 17 years now. In 2018, 8,260 civilian casualties were reported by Resolute Support, the mission run by NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) in Afghanistan.[i] Spearheaded by the Taliban, the Islamist movement that began in 1994 as a reaction to the depredations of warlords and local commanders, and the conflict between rival mujahideen groups, eventually developed transnational terror linkages with other radical Islamist entities such as the al-Qaeda, and transformed into a full-blown insurgency by the early 2000s.[ii] Despite the continued presence of US troops and the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan, the Taliban have established control over 12.3 percent of the country’s total 407 districts as of October 2018. Moreover, they have remained steadfast in their demands, primary of which are the exit of all foreign troops from Afghanistan, and the establishment of strict Islamic law that would dictate all manifestations of governance in the country.[iii] [iv] Even with foreign assistance, the Afghan government has failed not only to curtail the influence and operations of the Taliban, but also in negotiating peace with the militant outfit. Yet, it insists on sitting at the negotiating table, holding that any viable peace process would require the Afghan government at the helm.[v]

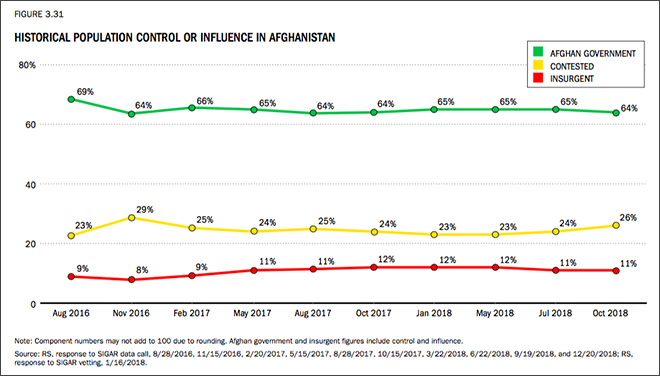

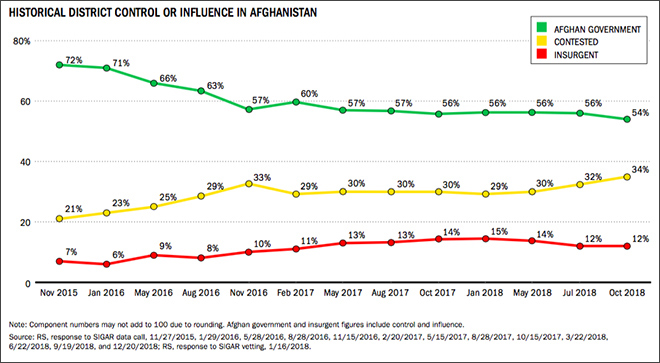

The recent rise in terrorist violence leading to the growing number of casualties has provoked a new sense of urgency for a negotiated deal, especially in light of the Trump administration’s desperation to disengage from Afghanistan. It is therefore unsurprising that the future of Afghanistan is once again a matter of serious global concern. According to the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) Report published in January 2019, the territory that the Afghan government exercises control over is home to 63.5 percent of the Afghan population, which is 1.7 percent lower than the previous quarter; the Taliban’s territorial gains, meanwhile, have translated to control over 10.8 percent of the population.[vi] In other words, the government controls just over half of the total inhabited area in Afghanistan, with the remaining territory being either in Taliban hold or is contested. (See Graphs 1 and 2, and Map 1.) Although the Taliban have faced political rifts among its senior leaders in 2012 that resulted in the dismissal of insubordinate commanders, and a crisis of leadership in 2015 after the death of Taliban chief Mullah Omar two years earlier became public news, the group has remained largely cohesive.[vii] It continues to be a grave threat to the people and the socio-political institutions of Afghanistan, and to the larger geopolitical calculus that Afghanistan is an integral part of.[viii]

Graph 1. Control of Afghan Population: Government, Taliban, Contested (Aug. 2016 – Oct. 2018)

Graph 2. Control of Afghanistan Districts: Government, Taliban, Contested (Nov. 2015 – Oct. 2018)

Considering the current debilitating conditions prevailing in Afghanistan, reconciliation with the insurgents seems to be the necessary but difficult step towards achieving some semblance of peace in the country. Zalmay Khalilzad, the US Special Representative for Afghanistan Reconciliation, is tasked to lead and coordinate US efforts to bring the warring parties to the negotiating table, while working in concert with the Afghan government.[xi] A rapprochement with the Taliban, however, is no guarantee for enduring peace, and seems an unlikely outcome in the first place. Moreover, it seems that US efforts to facilitate negotiations with the Taliban are part of a carefully thought out strategy to exit the country without having to endure the humiliation of admitting defeat.[xii]

Understanding the politics of reconciliation

In the history of negotiations with insurgent groups in Afghanistan, it is difficult to find even a single period of sustained peace. Even in the 1980s, much before the emergence of the Taliban as a separate entity, the Afghan mujahideen were regularly holding peace negotiations with the Soviet-backed Afghan government, under the National Reconciliation Policy (NRP) of the Najibullah government, initiated in 1986.[xiii] However, in the absence of financial and military aid from the USSR, Najibullah failed to maintain control over the Afghan armed forces, as well as national political institutions, leading to the collapse of the government.[xiv] The Geneva Accord of 1988, which comprised three bilateral agreements signed between the governments of Afghanistan and Pakistan, in the presence of representatives from the US and USSR as guarantors, also failed to end the war in Afghanistan.[xv] For one, the mujahideen were not directly involved in the negotiations and felt that the diplomatic exercise was a strategy to systematically marginalise them, by pushing them to the periphery of the decision-making process.[xvi] Moreover, the Accord failed to calibrate a potential power-sharing agreement that would take into account the interests and participation of all possible domestic stakeholders, including the various militias.[xvii]

What followed was a state of anarchy, as the groups that were collectively referred to as the mujahideen, began vying for political and administrative control of Afghanistan.[xviii] Reacting to the civil war initiated by the mujahideen outlaws, a small group of students led by Mullah Omar, created the Taliban, a movement that vouched to unify the country, rid the Afghan soil of all “vices”, and act as a formidable opponent to the warring mujahideen.[xix] Not only did the Taliban capture the city of Kabul and declare political legitimacy, but also castrated and killed Najibullah, the last Soviet-backed president of Afghanistan, and established strict Islamic rule.[xx]

Although reconciliation on the whole has remained elusive, engaging in a process of dialogue and discussion with the mujahideen forces was somewhat easier than accomplishing the same with the Taliban. Possibly owing to the lack of technical sophistication of the mujahideen, the Afghan establishment in the era of the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) were able to devise a shrewd counter-insurgency strategy that involved deceptive strategic maneouvring.[xxi] The fact that the Afghan state was a fairly functional entity in the 1980s, as opposed to that post-2001, may have been one of the driving forces of the reconciliation programme created by the PDPA government. The Afghan Intelligence Service in the 1980s successfully infiltrated the ranks of the mujahideen, established clandestine links with most of the prominent commanders of the movement, and convinced the insurgents to sign protocols enumerating respective political and administrative jurisdictions.[xxii] One such important agreement was the protocol signed between Ahmed Shah Masood’s Shura Nizar and the Afghan government, which signaled truce in the Panjshir Valley in 1984.[xxiii]

The distribution of arms and local currency among opposition forces—a move mastered by the Najibullah regime from 1989-1992, in order to coopt the insurgents into accepting the status quo—yielded better results than arming government supporters against the militias.[xxiv] However, soon after the withdrawal of the Soviets from the country and the subsequent fall of the USSR, Russia decided to stop all military and economic aid to Afghanistan, which was a contributing factor to Najibullah stepping down as president, along with a number of desertions in his own military establishment.[xxv] Although Najibullah failed to accomplish a negotiated political settlement with the mujahideen, his reconciliation strategy achieved, albeit briefly, the limited objective of precluding defeat, if not securing an outright military victory.

Successive efforts at reconciliation between the insurgents and the Afghan government similarly failed to resolve the long-drawn conflict. One such effort took the shape of the Peshawar Accord of 1992, which provided for the creation of the Afghan Interim Government (AIG) to be headed by Sibghatullah Mojaddedi, leader of the Afghan National Liberation Front, one of the smallest and the least potent of the ‘Peshawar 7’ or the seven major mujahideen parties fighting government forces.[xxvi] [xxvii] However, the AIG under Mojaddedi, and thereafter Rabbani, could not withstand the friction among the various representatives of different mujahideen parties that constituted the governing body, and the constant threat of an attack by the Islamic fundamentalist Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, the chief of the strongest mujahideen party Hezb-i-Islami. This resulted in the escalation of the civil war.[xxviii] The UN-brokered Islamabad Accord of March 1993 that laid out a power-sharing arrangement between Burhanuddin Rabbani and Gulbuddin Hekmatyar by appointing the latter as prime minister, failed as well owing to shortcomings in the agreement itself.[xxix] As a result, despite having taken oath at the holy shrine of Mecca, the signatories to the agreement reneged and the civil war intensified.[xxx] The Mahiper Agreement of 1995 that reinstated Hekmatyar in the interim government under Rabbani was another failed attempt at establishing political stability in the country, as the Taliban began to launch rocket attacks on the city of Kabul.[xxxi]

When the Taliban captured the city of Kabul in 1996 and established themselves as rulers of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, the country was still being plagued by the civil war that began in 1989. The emirate established by the Taliban, however, gained the support and recognition of states such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Pakistan, despite the lack of domestic backing and an opposition in the form of the Northern Alliance. Arguably, one of the most significant setbacks faced by the Taliban, was the failed attempt at capturing and subsequently holding onto the northern city of Mazar-i-Sharif in early May 1997.[xxxii] Soon after proclaiming that they have established control over the city with the help of Gen. Abdul Rashid Dostum’s disloyal lieutenant Abdul Malik, the Taliban suffered an embarrassing defeat at the hands of the opposition coalition known as the National Islamic Front for the Deliverance of Afghanistan, also known as ‘Junbish’, headed by Ahmed Shah Masood.[xxxiii] Upon defeat, although the Taliban retreated to Kunduz to recoup, they continued to make territorial gains in various parts of the country. In 1998, the Taliban launched another attack on the northern mujahideen forces, ultimately occupying Dostum’s headquarters in Shiberghan and effectively, the city of Mazar-i-Shairf.[xxxiv] Meanwhile, the UN facilitated ‘Six Plus Two’ talks involving the six neighbouring countries of Afghanistan (Iran, China, Pakistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan), along with the US and Russia. The talks failed to make any progress in bringing the Afghan war to an end.[xxxv]

Another blow to the Taliban regime in Afghanistan came after the 1998 bombings of the US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania that were orchestrated by the al-Qaeda, a Taliban ally.[xxxvi] As a result, Afghanistan became the target of US cruise missile strikes, as the leader of al-Qaeda, Osama bin Laden, was suspected of operating out of militant bases in the country. In 1999, the UN adopted Resolution 1267 that imposed economic sanctions and an air embargo on the Taliban regime, to force compliance on them to hand over Osama bin Laden for trial.[xxxvii]

A brief turnaround came in 2001, when the al-Qaeda orchestrated the assassination of Ahmed Shah Masood, the leader of the Northern Alliance, as a favour to the Taliban. Masood’s assassination was proof of growing organisational bonhomie between the Taliban and Osama bin Laden’s al-Qaeda, which was going to be exploited by the al-Qaeda after the deadly terror attacks of 9/11, by claiming safe havens in Afghanistan. However, the attacks of 9/11 once again changed the strategic dynamic in favour of the Northern Alliance, which had been bought over by the US, to cooperate with CIA paramilitary officers and the US Army Special Forces.[xxxviii] Supported by the US airpower and a task force of US Marines, the NATO-Northern Alliance coalition launched multiple offensives at Bamiyan, Jalalabad, Herat, Kabul, and Taloqan, and forced the capitulation of the Taliban regime.[xxxix] The impact of Operation Enduring Freedom, the US military campaign supported by the British to displace the Taliban from power, sustained through the next few years, under the interim government headed by Karzai that was the outcome of the Bonn Agreement.[xl]

The first bona fide reconciliatory effort after the complete dissipation of the Taliban in 2001, was made in 2005. Initiated by the Karzai government, Takhim-e-Solh or the Commission for Strengthening Peace and Stability (PTS) was launched as an integral component of the national reconciliation strategy.[xli] The PTS was premised on a trade-off, wherein the Taliban fighters were encouraged to submit an application stating they would not attack the government apparatus and follow the Afghan Constitution, in return being promised to be spared by the Afghan government.[xlii] Karzai’s reconciliation programme, however, did not secure for the Taliban any immunity from attacks by international forces such as the US military, and provided no guarantee of even minimal financial support to the de-radicalised but unemployed belligerent.[xliii] The PTS failed to acquire credibility as a coherent peace-building strategy. Later on, the Afghan Peace and Reintegration Program (APRP), launched by Karzai at the Afghan Consultative Peace Jirga in 2010, aimed at creating a socio-economic environment for conflict transformation, peace and stability, failed to secure considerable gains as well, as sluggish reconciliation stalled reintegration.[xliv] Although the APRP was touted as the backbone of the Afghan High Peace Council (HPC), and despite receiving support from the UN Development Program and ISAF’s Force Reintegration Cell (FRC), it was unable to negotiate a political settlement with the insurgents.[xlv]

Upon assuming office in 2009, US President Barack Obama announced a new strategy for the war effort in Afghanistan, of which the core objective was going to be “to disrupt, dismantle, and defeat al Qaeda and its safe havens in Pakistan, and to prevent their return to Pakistan or Afghanistan.”[xlvi] Along with ordering another 17,000 US soldiers to be sent to join the 36,000 American troops in Afghanistan, Obama expressed the intent to initiate a drawdown beginning in 2011: “Our troop commitment in Afghanistan cannot be open-ended, because the nation that I’m most interested in building is our own.”[xlvii] There was, however, no announcement of a coherent strategy for co-opting the Taliban into a political settlement with the Afghan government.

It was much later in 2012/2013 that the US administration, on the steadfast advocacy of Richard Holbrooke, the US Special Representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan at the time, was able to bring the Taliban to agree to participate in potential peace talks at the soon-to-be established political office of the Taliban in Qatar.[xlviii] However, bipartisan opposition in the US Congress to the proposed prisoner swap that was to release five Taliban prisoners from Guantanamo Bay, Cuba in return for the release of one American soldier in Taliban captivity, led to the collapse of the idea of reconciliatory talks.[xlix] The Paris conference in 2012, comprising representatives of the major political factions of Afghanistan along with the delegates from the High Peace Council, did not result in any agreement; nor did the Kyoto meeting, which saw consultations take place between the head of HPC, Masoom Stanekzai and active Taliban representatives, also in 2012.[l]

Early this year, in an unprecedented move, Afghan President Ashraf Ghani extended a largely unconditional offer of peace talks to the Taliban. Despite declaring an open-ended military commitment in the Afghan conflict in early 2017, and stating that the US would assume a tougher approach towards Pakistan for the latter’s continued support to the Taliban and other insurgent groups, the Trump administration too has lent unequivocal support to the idea of holding reconciliatory talks with the insurgents.[li] “Such an environment creates an impulse for everyone to renew their efforts to find a negotiated political settlement,” said Alice Wells, Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary to South & Central Asia, in keeping with the optimism surrounding reconciliation, created largely due to the Eid ceasefire observed in June 2018.[lii] As misplaced as the gathering optimism about reconciliation with the Taliban may seem to the majority, the American proponents of the concept seem to be increasing in number. They view reconciliation as a potentially disastrous but a necessary step in the current context, to stop the bloodshed and create a pretext for a defeated US to exit the country with minimal embarrassment.[liii]

Contextualising ‘reconciliation’

In 2014, the RAND Corporation published ‘From Stalemate to Settlement’, a report based on 13 case studies of insurgencies resolved through negotiations, to extrapolate lessons for Afghanistan.[liv] The report found that the essential ingredients to successfully combat an insurgency together form a master narrative that can be modified to suit the current stage of conflict in Afghanistan, characterised by acceptance, reconciliation, and finally, reintegration. Although an astute observation and formulation of a credible counterinsurgency strategy, the success of the narrative in the case of Afghanistan cannot be guaranteed due to a number of reasons. What makes it unlikely that a settlement between the insurgents and the Afghan government will be reached are certain externalities beyond the parties’ control, and their uncompromising stances. To begin with, and most importantly, the Taliban are perceived as the emerging winners in the conflict—as such, they do not feel obligated to even engage in negotiations with the Afghan government, let alone strike a peace deal.

As things are, the realisation of a mutually destructive stalemate[lv] is far from being reached: the Taliban’s control over Afghan districts is steadily increasing, even as they are embroiled in combat with ISAF and Afghan forces.[lvi] The SIGAR report published in January 2019 states that the data provided by Resolute Support, NATO’s mission in Afghanistan, on district and population control exercised by the Taliban, is indicative of neither the efficacy of America’s South Asia strategy nor the security situation in Afghanistan. There are, however, other reports refuting the American claim.[lvii] The NATO mission in Afghanistan is said to be using “influence” as a measure, which is not a quantifiable concept to begin with, and manipulating numbers to suit their agenda of a hasty departure from the country.[lviii] Moreover, there is minimal evidence to suggest that US air strikes on suspected operational units of the Taliban, and bases for opium cultivation (a major source of revenue for the Taliban), have been significantly harmed.[lix]

When President Ghani offered to conduct unconditional peace negotiations with the Taliban in February 2018, the Taliban responded with their characteristically vehement denial of direct communication with the Afghan government, who they consider to be American “stooges”.[lx] The Taliban’s response to the offer of talks (“without preconditions”) is an indication of their obtuse determination to disregard the request of the Afghan government to partake in decision-making regarding the future of Afghanistan.[lxi] On the final day of the three-day Eid ul-Fitr ceasefire observed by the warring entities in June 2018, the Taliban announced that they would resume the fight, even in the face of an announcement by the government that the latter would be extending the ceasefire by another 10 days.[lxii]

Theoretically, for the insurgents to be accepted as legitimate partners at the negotiating table, they must first reconcile with the futility of sustained conflict.[lxiii] However, recent developments indicate that the anti-insurgent forces cannot afford to wait for the insurgents, in this case the Taliban, to realise the futility of war, given the high number of casualties on their side, and the consistently increasing district and population control of the insurgents.

Another factor determining the success of negotiations with insurgents is the role played by external forces that are active and operational in the conflict zone. Exemplified in the case of the insurgency in Tajikistan from 1992 to 1997, the role played by the region’s strongest power Russia, in pushing the Tajik government to accept the terms of the National Reconciliation Accord was a crucial driver.[lxiv] The armistice was bolstered by the acceptance of the terms of the newly formulated power-sharing agreement, with support from the United Nations.[lxv]

In the case of Afghanistan, the willingness of external stakeholders to support a peaceful resolution of the conflict, is convoluted. While the pro-government United States has explicitly stated its acquiescence for engaging with the Taliban in a series of negotiations aimed at a truce, Pakistan continues to provide material and logistical patronage to the militant outfit.

In the 1980s, Pakistan had invested heavily in the militant leadership of Hekmatyar, and later in the Taliban, to achieve “strategic depth” in Afghanistan, and leverage that to balance America’s relationship with India vis-à-vis that with Pakistan.[lxvi] In that sense, it is the complex nature of the Islamabad-Kabul relationship that poses more of a challenge to lasting peace in Afghanistan than confrontation between US troops and the insurgents. Pakistan’s continued material support to the Taliban, as well as provision of safe havens for terrorists from Afghanistan, can partly be explained by their need to cultivate proxies to counter India’s growing influence in Afghan political circles. US efforts at convincing Pakistan into severing linkages with the Taliban and the Haqqani Network, have been repeatedly ignored, and despite a 60-percent cut in US military aid, Pakistan continues to support the Afghan insurgency.[lxvii] There is also conjecture in the US military establishment about Russia smuggling weapons across the Tajik border to the Taliban; Moscow has refuted such claims.[lxviii]

Between the devil and the deep blue sea

Having suffered heavy military casualties over the years, and cognisant of the fact that the Afghan government forces fighting the insurgents are increasingly losing ground, it is understandable for the US to sway in favour of a negotiated settlement with the Taliban. Although there is no guarantee that a truce with the Taliban would last long, or even that the insurgents would keep the integrity of the agreement intact, settlement is increasingly being perceived as the only viable option to bring an end to the long-drawn war.

The draft settlement framework outlined (but not yet agreed upon) by the Taliban and the US in the Qatar peace talks held in January 2019, under the stewardship of Khalilzad, has been considered a breakthrough.[lxix] It focuses on the insurgents guaranteeing that Afghan soil is never again used by terrorists to devise attacks, in particular against the US, agreement to a ceasefire, and direct talks with the Afghan government, following which the US would initiate a complete withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan.[lxx] The important point to understand is why the Taliban have agreed to negotiate a peace deal with the US in the first place, given that they are increasingly emerging as winners in their fight against the coalition of the Afghan government and US forces. For the Taliban, engaging in conciliatory talks with the US, which is likely to precede a complete US pullout from Afghanistan, serves their long-term objective of fighting and subsequently defeating the ill-equipped and inadequately trained Afghan forces, in the absence of American protection.[lxxi]

The present-day scenario is one of an “imbalanced stalemate”. In other words, whereas on the one hand neither party is capable of securing an outright military victory in the near future, the balance of power is undoubtedly tilted in favor of the Taliban. Moreover, maintenance of troops in Afghanistan is not only expensive for the US, but also the numbers are neither small enough so as to not be perceived as a looming threat by the Taliban, nor large enough to change the course of events.[lxxii] A complete US withdrawal from Afghanistan serves America’s limited objective of securing an exit without humiliation, and would be a move aligned with the demands of the Taliban, who wish to decide the future for Afghanistan on their own terms, in the absence of foreign actors.

The latest round of negotiations that took place in Moscow in February 2019, between the Taliban and prominent Afghans, including former president Hamid Karzai, did not witness the participation of the Ghani government, evoking anger from the latter. The talks did not arrive upon a suitable timeline for American withdrawal, but produced a nine-point “basic vision” for post-insurgency Afghanistan. The vision emphasised on a commitment to creating a strong yet inclusive central government, and respect for the fundamental rights of the citizens.[lxxiii]

There are fears that negotiations with the Taliban, taking place in the absence of US representatives and Afghan government officials, may further polarise an already fragmented Afghan socio-political milieu, given that they are being attended by Afghan leaders who are vying for electoral legitimacy in the upcoming presidential elections.[lxxiv] President Ghani’s office has proclaimed that negotiations in the absence of official Afghan representation will further undermine the fragile Afghan political apparatus, and any peace deal that comes out of such meetings will be unable to secure government sanction at the time of implementation.[lxxv] Moreover, President Ghani is not in favour of a complete and immediate US troops pullout, and has written to Trump offering a significant cost reduction in the maintenance of US troops on Afghan soil.[lxxvi] The offer has garnered criticism in Afghan political circles, as the US is believed to be the biggest ally of the Ghani-led government, a relationship that potentially holds the key to Ghani’s re-election in July 2019.[lxxvii]

There are views that support the idea that since the Taliban of today are not the “monolithic” organisation that they used to be in the 1990s, the Afghan government must venture towards neutralising the non-ideological or the moderate members of the insurgent group, to retain any hope for reconciliation.[lxxviii] However, neither in the 1990s nor today, the Taliban are not a monolithic entity, given the ideological variations within the group. Attempts at integrating the moderates into mainstream politics have proved counter-productive, further aggravating the hardliners.[lxxix] The fact that Mullah Rabbani, one of the more moderate leaders of the Taliban in the late 1990s, was eventually sidelined by the Amir-ul-Mumineen Mullah Omar in 1998, fearing the potential emergence of a parallel and independent power base, and his loyalists expelled from the group, indicates the existence of divergent opinions even back then.[lxxx] Ahmad Shah Massoud had also made a number of efforts at negotiating with the moderate elements of the Taliban in the 1990s, such as Mullah Rabbani, but they failed as the latter were eventually decimated by the fanatical members of the group, who were the core constituents of the Taliban.[lxxxi] Many of the less radical elements of the Taliban too—which were integrated into the Afghan government or convinced to serve as provincial members of the High Peace Council, based on the Afghan Peace and Reintegration Programme (APRP) born out of the London Conference of 2010—either faced threats or were assassinated by the extremists.[lxxxii]

Therefore, the success of a negotiated peace deal with the Taliban will hinge on the sustainability of the power-sharing arrangement that emerges as a result of conciliatory talks. If integrated into the official decision-making apparatus of the country, it will be safe to assume that the Taliban would ensure they wield a significant amount of political power, and would demand complete control of their core territorial bases such as Helmand, Uruzgan and Kunduz. Having said that, negotiated peace translated into a political settlement with the Taliban is likely to be short-lived, as there is little assurance, if at all, that the group would not resort to their old ways of brazen violence, or that they will even be able to secure popular legitimacy. If the past record of the Taliban is anything to go by, no guarantee or pledge can assure that the insurgents would not renege on their promise. With or without the US, therefore, Afghanistan will likely continue to see political instability and insurgent violence in the foreseeable future.

[i] “Quarterly Report to the United States Congress”, Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, p. 76, 30 January 2019.

[ii] “The al-Qaeda – Taliban Nexus”, Council on Foreign Relations, 24 November 2009.

[iii] “Quarterly Report to the United States Congress”, Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, p. 69, 30 January 2019.

[iv] Pamela Constable, “After gains in Afghanistan, resurgent Taliban are in no rush for peace talks”, The Washington Post, 3 December 2018.

[v] “Afghan Taliban, US to hold peace talks on Wednesday”, The Week, 8 January 2019.

[vi] Rod Nordland, “Afghan Government Control Over Country Falters, U.S. Reports Says”, The New York Times, 31 January 2019.

[vii] Matthew Dupeé, “Red on Red: Analyzing Afghanistan’s Intra-Insurgency Violence”, Combating Terrorism Centre, p. 26, 1 January 2018.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] “Quarterly Report to the United States Congress”, Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, p. 69, 30 January 2019.

[x] Ibid., p. 70.

[xi] “Special Representative for Afghanistan Reconciliation Zalmay Khalilzad Travel to Afghanistan, Pakistan, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia”, U.S. Department of State, 3 October 2018.

[xii] Anatol Lieven, “It’s Time to Trust the Taliban”, Foreign Policy, 31 January 2019.

[xiii] Heela Najibullah, Reconciliation and Social Healing in Afghanistan: A Transrational and Elicitive Analysis towards Transformation (Berlin: Springer, 2017), p. 90.

[xiv] Mohammed Ehsan Zia, “An Analysis of Peacebuilding Approaches in Afghanistan“, Asia Society.

[xv] Rosanne Klass, “Afghanistan: The Accords”, Foreign Affairs 66, No. 5 (1988).

[xvi] Mohammed Ehsan Zia, “An Analysis of Peacebuilding Approaches in Afghanistan“, Asia Society.

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] Scott Atran, “A Question of Honour: Why the Taliban Fight and What to Do About It,” Asian Journal of Social Science 38, No. 3 (2010), p. 348.

[xix] Ibid., p. 350.

[xx] Tim McGirk, “The day time ran out for Najibullah borrowed time runs out”, The Independent, 28 September 1996.

[xxi] Michael Semple, Reconciliation in Afghanistan (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press), p. 16.

[xxii] Ibid.

[xxiii] Ibid.

[xxiv] Ibid., p. 20.

[xxv] Thomas Ruttig, “Crossing the Bridge: The 25th anniversary of the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan”, Afghanistan Analysts Network, 15 February 2014.

[xxvi] Kenneth Katzman and Clayton Thomas, “Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security and U.S. Policy”, Congressional Research Service, p. 2, 13 December 2017.

[xxvii] Peshawar Accord, 24 April 24 1992.

[xxviii] Shah M. Tarzi, “Afghanistan in 1992: A Hobbesian State of Nature,” Asian Survey 33, No. 2, p. 168.

[xxix] “Afghan Peace Accord”, S/25435, United Nations Security Council, 19 March 1993.

[xxx] Mohammed Ehsan Zia, “An Analysis of Peacebuilding Approaches in Afghanistan”, Asia Society.

[xxxi] “Afghanistan Country Assessment”, Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, United Kingdom, October 2002.

[xxxii] Larry P. Goodson, Afghanistan’s Endless War: State Failure, Regional Politics and the Rise of the Taliban (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2001), p. 78.

[xxxiii] “Taliban Foes Set to Seize Northern Afghan Stronghold”, The New York Times, 12 June 1997.

[xxxiv] Larry P. Goodson, Afghanistan’s Endless War: State Failure, Regional Politics and the Rise of the Taliban (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2001), p. 78-79.

[xxxv] Ibid., p. 79.

[xxxvi] “The Bombings the World Forgot”, Foreign Policy, 21 September 2018.

[xxxvii] “The US War in Afghanistan: 1999-2018”, Council on Foreign Relations.

[xxxviii] Dick Camp, Boots on the Ground: A Fight to Liberate Afghanistan From Al-Qaeda and the Taliban (Zenith Press), p. 3.

[xxxix] Ibid.

[xl] Ibid.

[xli] Daisaku Higashi, Challenges of Constructing Legitimacy in Peacebuilding: Afghanistan, Iraq, Sierra Leone, and East Timor (New York: Routledge, 2017).

[xlii] Ibid.

[xliii] Ibid.

[xliv] Ibid.

[xlv] Neamat Nojumi, American State-Building in Afghanistan and its Regional Consequences: Achieving Democratic Stability and Balancing China’s Influence (Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016), p. 92-93.

[xlvi] “The US War in Afghanistan: 1999-2018”, Council on Foreign Relations.

[xlvii] “Obama’s Address on the War in Afghanistan”, The New York Times, 1 December 2009.

[xlviii] “The US War in Afghanistan: 1999-2018”, Council on Foreign Relations.

[xlix] “Peace Talks with the Taliban,” The New York Times, 4 October 2012, https://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/05/opinion/peace-talks-with-the-taliban.html.

[l] Omar Samad, “Afghanistan’s Track II rally,” Foreign Policy, 28 June 2012, https://foreignpolicy.com/2012/06/28/afghanistans-track-ii-rally/.

[li] Jonathan Landay, “Afghan President says Trump war plan has better chance than Obama’s”, Reuters, 20 September 2017.

[lii] Ayesha Tanzeem, “US Increases Push for Negotiated Settlement in Afghanistan”, Voice of America, 4 July 2018.

[liii] Anatol Lieven, “It’s Time to Trust the Taliban”, Foreign Policy, 31 January 2019.

[liv] Colin P. Clark and Christopher Paul, “From Stalemate to Settlement: Lessons for Afghanistan from Historical Insurgencies That Have Been Resolved Through Negotiations,” RAND Corporation (Washington, DC: RAND Corporation, 2014).

[lv] Mutually destructive stalemate refers to a stalemate in which both sides are suffering but neither side has enough of an advantage to escalate toward victory.

[lvi] “Quarterly Report to the United States Congress”, Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, p. 69, 30 January 2019.

[lvii] Bill Roggio, “Analysis: US Military Downplays District Control as Taliban Gains Ground in Afghanistan”, FDD’s Long War Journal, 31 January 2019.

[lviii] Ibid.

[lix] Asfandyar Mir, “Afghanistan’s Road to Peace Won’t Be an Easy One”, The Washington Post, 30 March 2018.

[lx] Hamid Shalizi and James Mackenzie, “Afghanistan’s Ghani offers talks with Taliban ‘without preconditions’”, Reuters, 28 February 2018.

[lxi] Ibid.

[lxii] Shereena Qazi, “Afghanistan: Taliban resume fighting as ceasefire ends”, Al Jazeera, 18 June 2018.

[lxiii] Colin P. Clark and Christopher Paul, “From Stalemate to Settlement: Lessons for Afghanistan from Historical Insurgencies That Have Been Resolved Through Negotiations,” RAND Corporation (Washington, DC: RAND Corporation, 2014), p.4.

[lxiv] Ibid., p. 41.

[lxv] Ibid., p. 42.

[lxvi] Neamat Nojumi, American State-Building in Afghanistan and its Regional Consequences: Achieving Democratic Stability and Balancing China’s Influence (Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016), p. 214.

[lxvii] Vanda Felbab-Brown, “Why Pakistan supports terrorist groups, and why the US finds it so hard to induce change”, Brookings, 5 January 2018.

[lxviii] Justin Rowlatt, “Russia ‘arming the Afghan Taliban’, says US”, BBC News, 23 March 2018.

[lxix] Mujib Mashal, “U.S. and Taliban Agree in Principle to Peace Framework, Envoy Says”, The New York Times, 28 January 2019.

[lxx] Ibid.

[lxxi] Adam Taylor, “U.S.-Taliban talks hint at change in Afghanistan. Here’s why”, The Washington Post, 28 January 2019.

[lxxii] Kimberly Amadeo, “Afghanistan War: Cost, Timeline, Economic Impact”, The Balance, 2 January 2019.

[lxxiii] Andrew Higgins and Mujib Mashal, “Taliban Peace Talks in Moscow End With Hope the U.S. Exits, If Not Too Quickly“, The New York Times, 6 February 2019.

[lxxiv] “U.S. Negotiator: Afghan Peace Possible Before July Elections”, Voice of America, 8 February 2019.

[lxxv] Andrew Higgins and Mujib Mashal, “Taliban Peace Talks in Moscow End With Hope the U.S. Exits, If Not Too Quickly”, The New York Times, 6 February 2019.

[lxxvi] Mujib Mashal, “To Slow U.S. Exit, Afghan Leader Offers Trump A Cost Reduction”, The New York Times, 30 January 2019.

[lxxvii] Ibid.

[lxxviii] Anne Stenerson, “Three Myths Holding Back Afghan Peace Talks”, The Global Observatory, 10 March 2017.

[lxxix] Ibid.

[lxxx] “The Taliban Biography: The Structure and Leadership of the Taliban 1996-2002”, The National Security Archive, 13 November 2009.

[lxxxi] Mariam Safi, “Talking to Moderate Taliban”, Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies, December 2007, p. 1.

[lxxxii] “Reconciliation with the Taliban: Fracturing the Insurgency”, Institute for the Study of War, 13 June 2012.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Shubhangi Pandey was a Junior Fellow with the Strategic Studies Programme at Observer Research Foundation. Her research focuses on Afghanistan particularly exploring internal political dynamics ...

Read More +