-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

While one can sense the positive sentiments across the market, albeit tentative, there is nothing to suggest that the end of the pandemic is near — or that oil supply will remain shut-in.

The COVID-19 pandemic has already created ruckus across the globe by putting an unprecedented restriction on movement and bringing the global economy to a standstill. Coupled with this, an unsettled resolve to balance the oil market that resulted in an unsolicited oil price war among OPEC+ countries has created downward pressure on oil demand in the market, which was already swamped with crude oil.

Even a late attempt to rescue the market by the OPEC+ along with G20 countries, by signing a historic new OPEC deal on 12 April, failed to gauge the markets as it did not commensurate with pandemic-induced falling demand. On 20 April, when West Texas Intermediate (WTI) futures contract for May ended in negative territory, it stunned the oil market, moving deeper into contango.

However, the recent rally of WTI futures for the June contract has sprung a further surprise on growing signs of a rebound in oil demand, though evidence favoring this optimism suggests otherwise. June futures, which expired on 19 May, showed no sign of repeating historic plunge of May futures on 20 April, after it settled at $32.50 a barrel, which was even higher than the front-month July contract recorded at $31.96, marking a shift from contango to backwardation.

Earlier, to offset catastrophically low oil prices, the Declaration of Cooperation at the 9th and 10th (Extraordinary) OPEC and Non-OPEC Ministerial meetings was held on 9-10 and 12 April 2020 to sign a new OPEC+ deal along with G20 countries. Accordingly, crude oil production cuts were agreed upon by 9.7 million barrels per day (mb/d) for May and June 2020; by 7.7 mb/d from 1 July 2020 to 31 December 2020; and by 5.8 mb/d from 1 January 2021 to 30 April 2022.

While it was amply clear that the new OPEC+ agreement would not offer immediate respite in balancing the oil markets, it was also unthinkable for several analysts that production of few more barrels by the US and Saudi Arabia till the time deal becomes effective in May would ever test oil storage and pipelines capacity in Cushing, Oklahoma on April 20, when WTI futures went negative.

Up to 10 April 2020, the US was already producing large amounts of crude at 12.3 mb/d, making it the largest producer in the world after Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia on the other hand, more than doubled its oil shipment to the US from 366,000 barrels per day (bp/d) in February to 829,540 bp/d in March, without gauging the storage capacity at Cushing. This prompted US oil benchmark to shed $55.9, or over 305%, to settle at -$37.63 a barrel on the New York Mercantile Exchange on 20 April.

The reasons why WTI futures recorded a historical low into the negative territory were simply due to the production and export of oil without being mindful of the limited storage space at Cushing, Oklahoma. This prompted producers to pay their customers to help them get rid of the oil they have pumped.

It may be noted that, the WTI contract is physically set up and in case buyers and sellers do not close their position before expiry, they must make or accept delivery of crude that takes place in Cushing, Oklahoma. At the expiry, the value of futures reflects the value of crude in that place and time, which itself is influenced by the logistics of that place. Cushing, Oklahoma, which is the delivery location for the NYMEX benchmark Light Sweet Crude Oil futures contract, is home to 90 million barrels of storage capacity across 15 storage terminals and home to a network of two dozen pipelines. Cushing’s working capacity, accounting for 76 million barrels against its maximum capacity of 80 million barrels, were all booked on 20 April, prompting crude to end in negative territory.

Thus, with on-land sites already booked and floating storage reaching a record high of 160 million barrels, a 100% jump over the week preceding that day, amidst refineries unwilling to refine crude into petroleum products due to lockdown, the WTI May future had nowhere to go but in negative territory to touch -$40.32 a barrel, before closing at -$37.63 a barrel on 20 April.

Even as the furious rise of US benchmark from a negative terrain to over $32 a barrel in a month signals some money rushing back to oil, this swift turnaround from super-contango to backwardness suggests WTI is running on fumes.

Though planned production cuts under new arrangements would be viewed positively by oil markets, the difficulty for Saudi Arabia to find storage for its oil and hence curtailing its oil production further, coupled with easing of the lockdown in countries beyond China, would work in favour of oil market sentiments.

However, such ease in lockdown does not make the oil and gas industry readily available to resume activities across the value chain. As Rystad Energy’s VP of Oilfield Services, Matthew Fitzsimmons stated, “When the virus and the quarantine measures have been eased and it is safe to get back to work, it doesn’t mean the same work can be done with the same intensity because the weather windows could be missed and that can push maintenance even to the next year.”

According to International Energy Agency’s (IEA) May report, oil market outlook has improved from its previous month, which its director, Fatih Birol, termed as ‘Black April’. Two basic reasons cited by the May report for recovery are the easing of lockdown measures and steep production declines in non-OPEC countries that corresponds to the commitment made by the new OPEC+ agreement. According to the report, the month of May could see a considerable drop in the confinement of people from a recent peak of 4 billion to about 2.8 billion worldwide, signifying limited reopening of the business, albeit a modest one, with limited mobility. Hence, IEA has raised its previous month’s forecast of oil demand in 2Q20 from 9.3 mbd to -8.6 mbd.

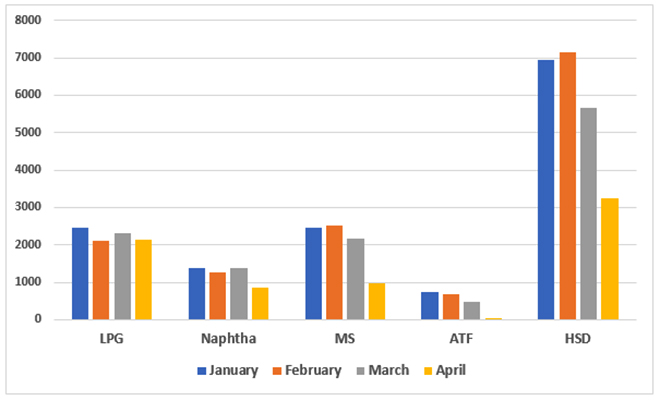

In India, for instance, lockdown shall continue to remain in force up to 31 May, with some ease of restriction in non-containment zones, with the inter-state and intra-state movement of passenger vehicles and busses with mutual consent of the States/Union Territories involved. This offers an opportunity for India to improve its petroleum consumption, particularly, petrol and diesel, from the levels of April 2020 (figure).

Figure: Consumption of select petroleum products in ’000 metric tonnes (Jan-April 2020)

Source: Petroleum Planning and Analysis Cell

Source: Petroleum Planning and Analysis CellAnother factor that helped reversed the WTI benchmark was the first drawdown of US crude oil inventories since mid-January by a modest 745 million barrels over the week, while that at Cushing, the WTI delivery hub, it fell a little over 3 million barrels. The fall in gasoline (or petrol) inventories by 3.51 million barrels, with a concurrent increase in its demand by 734 mbd, signaling one more sign of initial recovery.

China, where the future of oil rests is also witnessing oil demand and getting back to the pre-virus crisis level at about 13 mbd, almost reaching the levels of 13.4 mbd in May 2019. Recently, China became the first oil-consuming country during the pandemic to cooperate with OPEC in contributing to the rebalancing of the oil markets based on international market rules.

While the above evidence suggests some initial hopes for a revival of the oil markets post-cautious easing of the lockdown, with the resumption of limited economic activities in a controlled atmosphere, the risks of increased cases in COVID-19 need to be factored in. Besides, a new outbreak, which has again emerged in China in the northern provinces of Jilin and Heilongjiang is creating more uncertainties due to virus mutation, thereby hindering control efforts and delaying the recovery of patients.

On the flip side, the early recovery of the WTI oil benchmark would test the compliance of oil producers in the Permian Basin, which are ready to start production. This could be a disaster due to the spread of the virus, prompting a lockdown and triggering the second fall in oil prices. Besides, any further oil shipments from Saudi Arabia to the US could once again challenge the limited storage capacity in Cushing Oklahoma.

Thus, while one can sense the positive sentiments across the market, albeit tentative, there is nothing to suggest that the end of the pandemic is near, or that oil supply will remain shut-in. So, treading cautiously with gearing up for the second wave of pandemic without risking the livelihood and bringing the global economy out of intensive care, albeit at its own pace, would remain a challenge for the oil and gas sector in months to come. This itself is pre-conditioned on the pandemic if it is on a way to some sort of resolution, which currently is not the case.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Manish Vaid is a Junior Fellow at ORF. His research focuses on energy issues, geopolitics, crossborder energy and regional trade (including FTAs), climate change, migration, ...

Read More +