-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

This article is part of the series The COVID-19 Vaccine Challenge: Contextual and Country Analysis.

This article is part of the series The COVID-19 Vaccine Challenge: Contextual and Country Analysis.

In mid-July 2021, hospitals in the Java-Bali region—Indonesia’s most populous island-region—struggled with a surge in COVID-19 patients that had started following the Eid-ul-Fitr holidays in May, amid devastating news of makeshift cemeteries. Cases exceeded 56,000 and 1,000 deaths per day, a record daily high since the beginning of the pandemic in March 2020. During the week of 12 July, 32 of Indonesia’s 34 provinces reported an increase in cases while 17 experienced an increase of 50 percent or more. The Delta variant was reported in 21 provinces. Many feared that the health system would collapse unless stringent measures were urgently implemented. The end of July brought tentative signs of a drop in new cases, but it remained to be seen whether the downward trend would persist.

This situation stood in stark contrast to the cautious optimism that had prevailed in Indonesia just prior to the May holiday period. COVID-19 cases had hovered around 5,000 per day since March; economic activity was rebounding, albeit at a slow pace. Much of the optimism hinged on the rollout of the national COVID-19 vaccination campaign, launched in January 2021, making Indonesia a frontrunner amongst low- and middle- income countries in securing vaccines for its population and deciding to provide them free of charge. Public expectations were high. When asked what the Indonesian government could do more to strengthen its COVID-19 response, 57 and 48 percent of respondents to an online survey in November 2020 had ranked rollout of the COVID-19 vaccination programme amongst the top three priority actions for the central and provincial governments respectively. Thirty eight percent had expected the vaccination to be made available to them before the end of 2020; another 39 percent before June 2021.

Much of the optimism hinged on the rollout of the national COVID-19 vaccination campaign, launched in January 2021, making Indonesia a frontrunner amongst low- and middle- income countries in securing vaccines for its population and deciding to provide them free of charge.

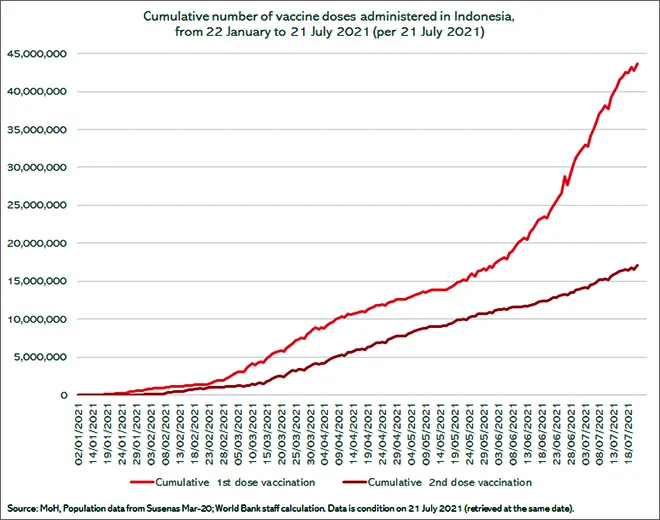

The vaccination rollout did not keep pace with these expectations. As of 26 July 2021, 8.7 percent of the population (18.1 million people) had been fully vaccinated. Meanwhile, 44.7 million people had received the first dose (figure 1). Initially, the slow rollout was linked to inadequate supply, a constraint that has been gradually lifting, and rollout picked up as the target population expanded from priority groups to all aged over 12 years. As of 23 July, Indonesia had received 151 million doses.

Figure 1

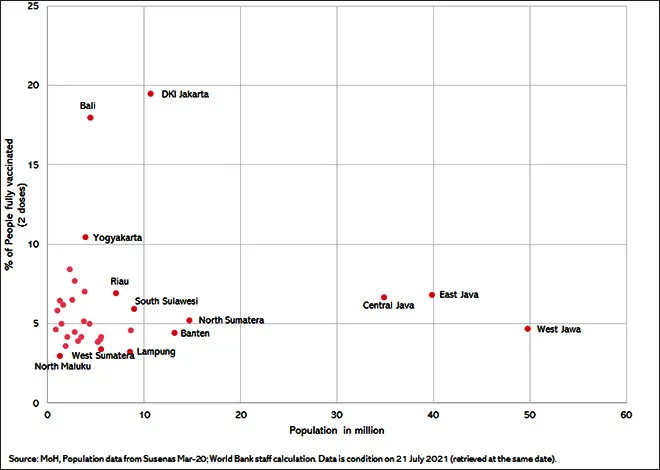

With the vaccine inventory growing, public attention has been shifting from concerns about adequacy to the need for improvement of logistics to speed up deployment. Vaccinations recently reached an encouraging high of one million a day, although daily numbers fluctuate significantly and rates varied widely across the country. This reflected in part the strategy to prioritise more densely populated urban areas with high infection rates, and in part the challenges of delivering services across the world’s largest archipelago (figure 2).

Figure 2

Supply constraints continued to be reported. Within provinces, some locations reported shortages due to high demand and queuing at health centres while others were unable to meet targets, leading some to link the slow uptake to vaccine hesitancy and the need for a stronger communication strategy. However, while experiences from across the world would suggest that vaccine hesitancy may become an increasingly important barrier as rollout progresses, initial estimates showed that hesitancy in Indonesia was relatively low, with nearly 80 percent of Indonesians willing to be vaccinated in March 2021. 70 percent of those who refused or were unsure cited concerns about side effects, safety, and effectiveness as the main reasons for their hesitance.

While experiences from across the world would suggest that vaccine hesitancy may become an increasingly important barrier as rollout progresses, initial estimates showed that hesitancy in Indonesia was relatively low, with nearly 80 percent of Indonesians willing to be vaccinated in March 2021.

However, this low hesitance, though encouraging, may change. Reports of misinformation that may cause Indonesians to lose confidence in the vaccine have been appearing in local media. It has been hypothesised that the low uptake among the elderly—a group prioritised since the launch of the campaign—may stem from vaccine hesitancy, in addition to difficulty accessing health centres and ineligibility due to chronic conditions (e.g., high-blood pressure). Reports of fully vaccinated individuals contracting COVID-19, including deaths amongst health workers and doctors, described concerns about the effectiveness of the Chinese vaccine, CoronaVac, the most widely used vaccine, in protecting against the Delta variant. At the same time, media reports that presented publicly available data in a more comprehensive manner documented the large differences in incidence of serious illness and death between the vaccinated and unvaccinated.

It is imperative that monitoring hesitancy and implementing efforts to curb it remain one of the government’s top priorities in the coming months as vaccination rollout progresses. Experience from high-income countries shows that information-related causes of hesitancy—including poor access to accurate information, misinformation, disinformation, rumours, and conspiracy theories, in particular through social media; and lack of effective public health messages—can all play an important role in impeding acceptance, in addition to `structural’ factors. In the US, for example, vaccination rates plateaued at 50 percent of the population despite the vaccine’s widespread availability and started to pick up recently only after COVID-19 became a “pandemic of the unvaccinated”.

Action is being taken around the world, using social media in particular, to manage what the World Health Organisation has termed an “infodemic” unfolding with the COVID-19 pandemic: An overabundance of information—some accurate, some not—that spreads alongside a disease outbreak. These efforts range from powerful social media messages in the UK to Bollywood celebrities in India promoting themselves when getting vaccinated in order to boost public confidence in the vaccine.

Past research in Indonesia suggests that celebrity endorsements on social media may influence beliefs about vaccination and knowledge of immunisation-seeking behaviour within social networks, and that online literacy programming can reduce belief in false news.

Indonesia has used social media influencers to promote confidence in the vaccine. This approach is promising but needs to be carefully designed as part of a comprehensive communication strategy and tested for effectiveness in changing behaviour before a broader rollout. Indeed, the reach of social media is extensive: Of the half of all Indonesian adults connected to the internet, 85 percent use social media platforms like WhatsApp, Facebook and Instagram, primarily for seeking and sharing news and information. Past research in Indonesia suggests that celebrity endorsements on social media may influence beliefs about vaccination and knowledge of immunisation-seeking behaviour within social networks, and that online literacy programming can reduce belief in false news. A global study that included Indonesia suggests that accurate information about descriptive norms (i.e., how many people in a country are willing to get vaccinated) can substantially increase an individual’s intentions to accept a vaccine.

With the country unwilling to enter a full lockdown, Indonesia’s only way out of the pandemic is a swift rollout of its COVID-19 vaccination programme, securing adequate supply of vaccines and improving the efficiency of the distribution process, combined with a continued emphasis on testing, tracing, and prevention measures and social distancing. As such, monitoring of public sentiment towards locally available COVID-19 vaccines will remain critical in coming months, and could be used to inform the design of customised communication strategies from trusted sources such as community representatives, healthcare providers, and local authorities. Such monitoring could also inform community engagement efforts involving champions, faith leaders, healthcare workers and others to raise knowledge and awareness about vaccinations, including socialisation of emerging (local) evidence on the positive impacts of vaccination. Health authorities should test how social media could be leveraged as a tool for aggressively promoting COVID-19 prevention measures and vaccination, in addition to its use in monitoring vaccine hesitance.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Ade Febriady is a consultant at the World Banks Indonesia Poverty and Equity Team. Currently he is working on Indonesia High-Frequency (HiFy) Household Survey on ...

Read More +

Rabia Ali is a senior economist with the World Bank's East Asia and Pacific Poverty and Equity team based in Jakarta Indonesia. Currently she is ...

Read More +

Ririn Salwa Purnamasari is a Senior Economist with the World Bank's East Asia and Pacific Poverty and Equity team working on Indonesia and Malaysia.

Read More +