-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

By 2030, only 77 percent are expected to have clean cooking fuel, leaving 1.9 billion with traditional sources of fuels

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), clean fuels and technologies are those that attain the fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and carbon monoxide (CO) levels recommended in the WHO global air quality guidelines (2021). Fuel and technology combinations are classified as clean if they achieve either the annual average air quality guideline level (AQG, 5 µg/m3 [micrograms per cubic meter]) or the interim target- 1 level (IT1, 35 µg/m3) for PM2.5; and either the 24-hour average air quality guideline level (AQG, 4 mg/m3) or the interim target-1 level (IT-1, 7 mg/m3) for CO. Under this definition, the WHO categorises solar, electric, biogas, natural gas, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), and alcohol fuels including ethanol as clean cooking fuels for PM and CO household emissions.

The report on tracking Sustainable Development Goal 7 (SDG 7), improving access to clean cooking fuels) notes that in 2021, 71 percent of the global population had access to clean cooking fuels and technologies. This means that about 2.3 billion people still use polluting fuels and technologies for most of their cooking. Even by 2030, which is the target year for attaining SDG goals, only 77 percent of the global population is expected to have access to clean cooking fuels, leaving 1.9 billion people to the mercy of solid fuels (biomass, wood, charcoal, crop, and animal waste) and kerosene.

The key driver behind the improvement in access to modern cooking fuels in Asia, particularly India is subsidised access to gaseous fuels, particularly LPG.

Not surprisingly, most of those who do not have access to modern cooking fuels are in the world’s poor and developing countries in Africa and Asia. While countries in Asia, particularly India, have substantially improved access to cooking fuels since the 2000s, the trend in Africa is one of stagnation or an increase in the number of people without access to cooking fuels. The key driver behind the improvement in access to modern cooking fuels in Asia, particularly India is subsidised access to gaseous fuels, particularly LPG.

Household wealth and socio-economic status (primarily higher education) are known drivers of access to and adoption of clean cooking fuels. For example, developed countries in Western Europe and North America have per person GDP (gross domestic product) above US$20,000 and 100 percent of their households have access to clean cooking fuels. Some developed countries, such as India, have followed a different approach to providing access to clean cooking fuels. Rather than having millions of households wait for incomes and socio-economic status to rise to a level that makes clean cooking fuels accessible and affordable, access to clean cooking fuels, such as LPG, is subsidised through policy. As a result, India has increased access to LPG to about 60 percent of households notwithstanding the fact that its per person GDP is just US$ 2410 in 2022 (current US$). In Côte d’Ivoire, West Africa, the share of households with access to clean cooking fuels is just 32 percent, though its GDP per person is comparable to that of India. Policy interventions explain the divergence in access to clean cooking fuels between the two countries.

Some developed countries, such as India, have followed a different approach to providing access to clean cooking fuels.

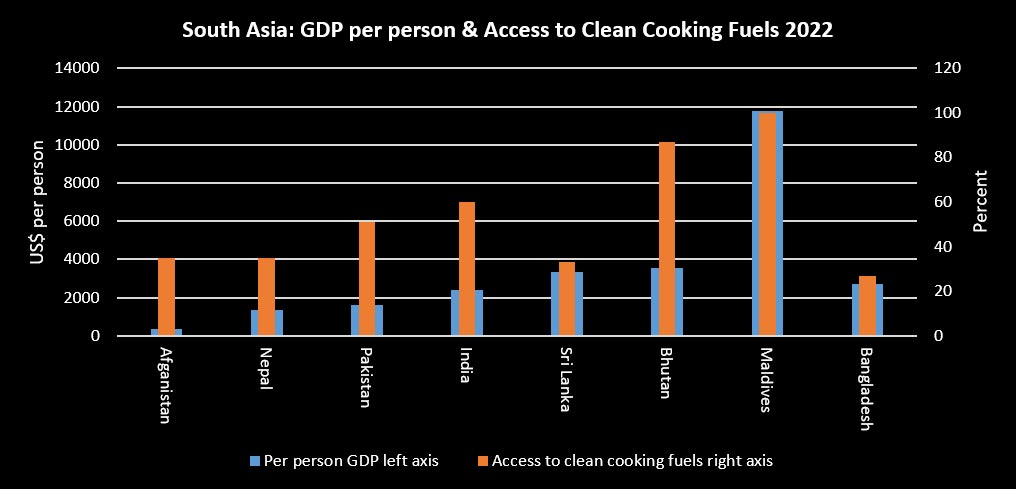

The divergence in the share of households with access to clean cooking fuels and per person GDP in South Asia provides a clear illustration of how policy can make up for the shortcomings of the market in providing equitable access to energy. Among South Asian countries, Maldives had the highest per person GDP of US$ 11,780 (current US$) in 2022 and 100 percent access to clean cooking fuels. Bhutan which had a per person GDP of US$ 3560, the second largest in South Asia, covered 87 percent of households with access to clean cooking fuels. However, Sri Lanka that had a comparable GDP of US$ 3354 covered only 33 percent households with access to clean cooking fuels. Sri Lanka’s per person GDP was nearly 10 times the per person GDP of Afghanistan, and yet Afghanistan had a higher share of households with access to clean cooking fuels at 35 percent. Bangladesh surpassed India’s per person GDP in 2020 and in 2022, Bangladesh’s per person GDP was US$ 2688, higher than that of India which was US$ 2410. However, Bangladesh had the lowest share of households with access to clean cooking fuels among South Asian countries at 27 percent while India’s share of households with access to LPG and piped natural gas was close to 60 percent. The wide difference in the share of households with access to clean cooking fuels among South Asian countries may be explained not only by household wealth but also by policy interventions.

Interventions in improving access to clean cooking fuels in India initially began at the state level when the LPG shortage eased in the late 1990s. Several southern state governments launched dedicated programmes for the distribution of subsidised or free LPG connections to households ‘below poverty line’ (BPL). This model was successful in galvanising political support for governments dispensing LPG programmes at the state level and was adopted by the centre in the form of the Rajiv Gandhi Gramin LPG Vitran (RGGLV) scheme in 2009. RGGLV more than doubled LPG dealers in rural areas and contributed to increasing LPG access in rural areas. Later in 2014 this programme was relaunched with some modifications as the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana programme that provided subsidised access to LPG. While the political pay out of the LPG access programmes that target private voters cannot be denied, they also substantially improve the welfare of poor households.

Subsidising LPG access is controversial. The liberal economic school categorically states that energy subsidies particularly fossil fuel subsidies (including LPG even though it is a clean fuel) have a net negative effect: they artificially lower fossil fuel prices, leading to market distortions that have environmental, economic and social consequences; they increase energy consumption and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, strain government budgets, divert funding that could otherwise be spent on social priorities such as healthcare or education and reduce the profitability of alternative energy sources.

Several southern state governments launched dedicated programmes for the distribution of subsidised or free LPG connections to households ‘below poverty line’ (BPL).

However, there is a less studied welfare argument for subsiding access to clean cooking fuels. The benefits of access justify some form of subsidy. For cooking, the poor often pay more for wood or other biomass-based fuels than they would for LPG, once the end-use efficiencies of the fuels are taken into account. Subsidizing access assists the poor in lowering their expenditures on energy for cooking, making finances available for other essentials like food and medicine and in avoiding all the problems of indoor air pollution.

The LPG subsidy in India, assessed by their relative efficacy, welfare benefits and cost-effectiveness is not necessarily net negative. In terms of efficacy, the subsidy reaches those for whom it is intended, the poor, through the direct benefit transfer model minimising errors of inclusion and exclusion. The welfare gains in providing energy access for cooking (increase of female literacy and engagement in productive activity, improvement in health particularly respiratory health of women and children in a household) are often much higher than the long-term costs involved in providing the subsidy. The subsidy is structured in such a way that it encourages provision of service at least cost as LPG does not involve elaborate infrastructure such as pipelines or transmission lines. This is one aspect that makes LPG subsidies more cost-effective in remote rural areas than gas pipelines or electricity distribution infrastructure (and service provision). Cost-effectiveness means that the subsidy achieves social goals at the lowest programme cost while providing incentives to LPG distributers to serve poor and rural populations.

The subsidy is structured in such a way that it encourages provision of service at least cost as LPG does not involve elaborate infrastructure such as pipelines or transmission lines.

Dependence on the invisible hand of the market for distribution of goods and services results in economic efficiency at the cost of equity. The visible hand of policy provides access to clean cooking fuels without having poor households wait for decades for economic benefits of the market logic to trickle through to them. The line of causality between economic growth and energy consumption runs both ways. This means that welfare benefits that accrue to poor households on account of higher energy consumption contribute to economic growth (education and employment of women). Energy subsidies and energy poverty are linked, and energy subsidies improve social well-being by mediating effects of energy poverty. What is required is not elimination of subsidy but innovation in energy subsidy for combating energy poverty and ensuring clean, sustainable, and affordable energy for all in line with the aims of the SDG7.

Source: World Bank

Lydia Powell is a Distinguished Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation.

Akhilesh Sati is a Program Manager at the Observer Research Foundation.

Vinod Kumar Tomar is a Assistant Manager at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Ms Powell has been with the ORF Centre for Resources Management for over eight years working on policy issues in Energy and Climate Change. Her ...

Read More +

Akhilesh Sati is a Programme Manager working under ORFs Energy Initiative for more than fifteen years. With Statistics as academic background his core area of ...

Read More +

Vinod Kumar, Assistant Manager, Energy and Climate Change Content Development of the Energy News Monitor Energy and Climate Change. Member of the Energy News Monitor production ...

Read More +