With 70 percent of the population with at least one dose and 60 percent of the population fully vaccinated, Massachusetts is one of the states leading the US in terms of vaccination rates. In fact, Massachusetts is only second to Vermont, a state with less than tenth of its population. Currently, anyone over the age of 12 is eligible for a vaccine, with no identification required. Massachusetts has been lauded for its high vaccination rates as a success story of an effective vaccination programme, but a closer look at the vaccination trends within the state reveal a more complicated picture.

Vaccine access and vaccine hesitancy both play a role in lagging vaccination rates, which are concentrated in economically vulnerable communities that were hardest hit by the pandemic.

Simply looking at vaccination rates at the state level provides an incomplete, reductionist picture of vaccine access in Massachusetts. Despite running one of the most successful state-level vaccination programmes and boasting the highest rates of vaccination in the country, vaccination rates remain divided along racial and socioeconomic lines. Vaccine access and vaccine hesitancy both play a role in lagging vaccination rates, which are concentrated in economically vulnerable communities that were hardest hit by the pandemic.

Correlating low infection risk and high vaccination rates

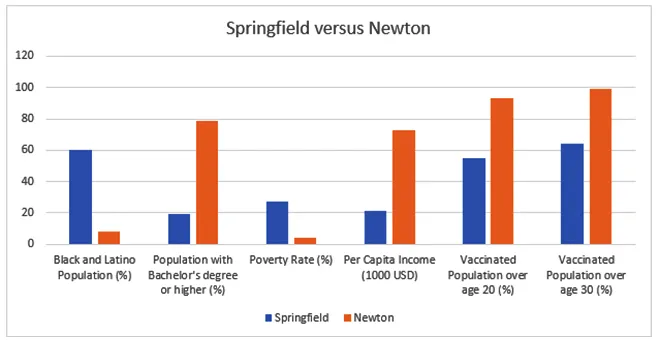

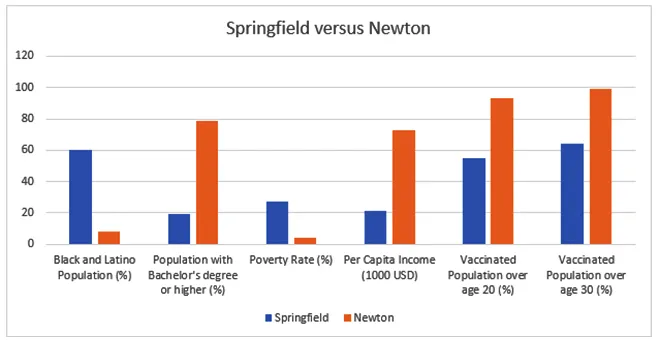

Table 1: Comparting population, education, poverty rate, income, and vaccinated population

Table 1: Comparting population, education, poverty rate, income, and vaccinated population

Take, for example, the cities of Newton and Springfield, as shown in Table 1. Newton is a majority white, affluent city on the outskirts of Boston that has vaccinated over 93 percent of people over the age of 20 and 99 percent of people over the age of 30. In contrast, Springfield, a town located in Western Massachusetts that is majority Black and Latino and ranks far lower than Newton in terms of income per capita, percentage of population with bachelor’s degrees or higher, and has a poverty rate of over six times that of Newton. Springfield has only vaccinated 55 percent of residents over 20 and 64 percent of residents over 30. These stark differences within Massachusetts highlight the disparities that education, income, and race play in equitable vaccine access and administration.

A study of vaccination to infection risk ratio in communities in Massachusetts found that communities with high socioeconomic vulnerability — such as Springfield — were more likely to be under vaccinated relative to their higher infection risk; where higher numbers of Black and Latino residents live in higher density, crowded housing, and work in essential sectors, leaving communities of colour more susceptible to outbreaks and positive cases. More affluent communities — like Newton — despite their low socioeconomic vulnerability and low infection risk, had significantly higher rates of vaccination. The under-delivery of vaccines to areas of higher socioeconomic vulnerability — which had larger proportions of Black and Latino populations — indicates a need to specifically target and monitor vaccine access for equitable vaccine distribution.

Vaccine access has been a multifaceted issue from the start of the rollout. Areas with higher concentrations of lower income residents and communities of colour already suffered from chronically lacking testing rates and with the start of the vaccination rollout, these communities were similarly distanced from the first possible ways of vaccination. The now-defunct seven Mass Vax sites were chosen with efficiency and high volume administration in mind and thus were placed in high capacity venues in large metro areas such as Fenway Baseball Park and Hynes Convention Centre. These Mass Vax sites failed to reach the communities of colour that were disproportionately impacted by the pandemic; the sites were physically distanced from the hardest hit communities. Individuals who could not reach the sites due to a lack of access or ability to afford transportation or could not afford to take time off work to travel to a vaccination centre. Additionally, there were several barriers to simply making an appointment; the process required internet access, health, language, and internet literacy to navigate the complex, multistep online sign-up process. Discomfort in vaccination spaces has also been a factor; undocumented immigrants and people of colour may be reluctant to step into vaccination centres with a large police presence.

The under-delivery of vaccines to areas of higher socioeconomic vulnerability — which had larger proportions of Black and Latino populations — indicates a need to specifically target and monitor vaccine access for equitable vaccine distribution.

Shifting focus to vulnerable groups

Although vaccine hesitancy remains an issue with misinformation regarding vaccine safety and a public distrust of the government in marginalised groups, the biggest issue as it stands is getting the vaccine to communities that cannot access it. Results show that concentrated local outreach with engagement involving key actors such as community members and leaders can help mitigate vaccine hesitancy. With around 60 percent of the population fully vaccinated and vaccination rates slowing down, the state government vaccine rollout has shifted resources to a more community-focused approach, with the shutdown of the seven Mass Vax sites and instead focusing on local centres and working with community partners.

Local grassroot campaigns have also popped up with the intent of addressing inequities in vaccine access. GOTVax, an organisation started by Boston area doctors, aims to get vaccines into the hardest hit neighbourhoods via tactics used to encourage voter registration during election years — phone banks, engaging with local leaders, and knocking on doors. The campaign has also recruited medical professionals and has partnered with the Boston Housing Authority (BHA) to vaccinate residents of low-income housing developments who may not be able to access vaccine clinics despite eligibility due to accessibility, such as the elderly and the disabled.

Local grassroot campaigns have also popped up with the intent of addressing inequities in vaccine access.

Recently, the state government has also launched a vaccine equity campaign aimed at vaccinating the 20 hardest hit communities, setting aside doses to go towards those communities. Community organisations can also now request a mobile clinic through the state vaccination website. However, active efforts to reach the communities that have been the most affected by the virus were not prioritised in the early days of vaccination as they perhaps should have been.

Addressing the issue of equitable vaccine access requires multifaceted approaches catered to the communities most disproportionality affected; so far, early state-led vaccination efforts failed to fully account for the structural racial and socioeconomic barriers in accessing vaccinations. Early vaccination rollouts were a testing ground for governments to find the most efficient method of administration and delivering vaccines and ended up prioritising volume and neglected to properly account for the marginalised who may not be able to access critical vaccines needed to protect themselves and their community. Vaccine equity in Massachusetts has been called the “best of the worst”; although doing better than other states in terms of equitable distribution, the rollout still needs systematic support of reaching hard hit and previously neglected communities. Without an active effort to make vaccine access equitable, vaccines may exacerbate pre-existing disparities caused by socioeconomic and racial inequalities and contribute to a looming public health issue.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV