-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

European efforts to find a footing in China present opportunities for India.

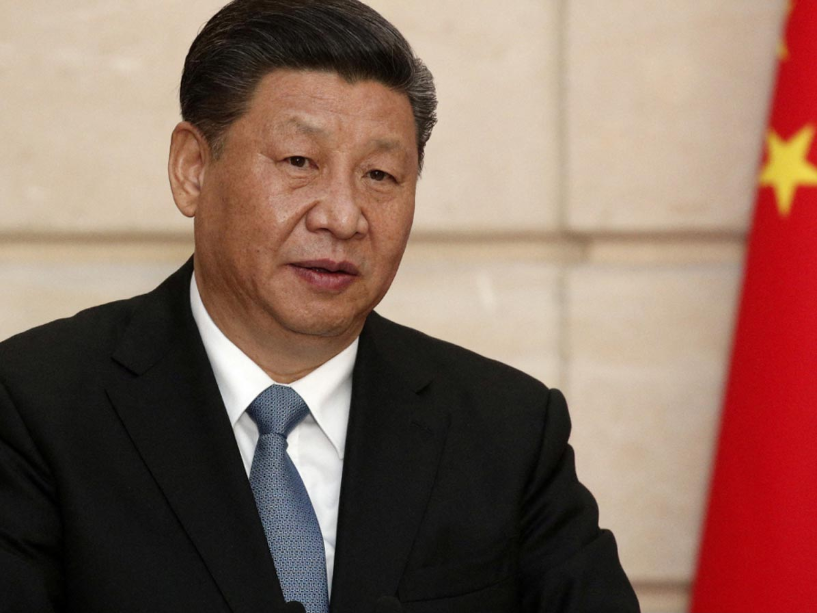

On May 5, Chinese president Xi Jinping arrived in France for a five-day Europe tour. Xi’s first trip to Europe in five years looks markedly different from his last one in 2019, when multi-billion-dollar deals were signed and Italy became the only G7 nation to join China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). In 2024, the European Union’s (EU) perception of China stands dramatically altered against a backdrop of rising trade tensions and concerns over Beijing’s “no limits” partnership with Moscow.

Xi’s first stop was France, which has time and again advocated for European strategic autonomy, often interpreted as scripting a third way between the US-China rivalry. Last year, President Emmanuel Macron ruffled feathers with his controversial comments on Taiwan, and more recently, during his speech at the Sorbonne, he urged Europe not to become a vassal of the US — music to Xi’s ears.

European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen’s presence in Paris was an attempt to present a united European front. Under her hardened approach, the EU has launched anti-subsidy probes into China’s electric vehicle (EV) sector and investigations into China’s procurement of medical devices. Just before Xi’s arrival in Europe, the Commission launched fresh crackdowns on TikTok and fashion retailer Shein. With allegations of overcapacity, unfair competition, and a ballooning trade deficit that stood at €400 billion in 2022, EU-China trade tensions are at their peak, underpinned by political tensions revolving around Chinese espionage activities, and exports of dual-use components aiding Russia’s war effort against Ukraine.

Even while Macron supports the EU’s “de-risking” approach and anti-subsidies probes, Paris, keen to attract Chinese investment in its own EV sector, has emphasised Europe’s need to rebalance trade ties with China. For Xi, Paris’ malleability, combined with its significant influence in the EU, is leverage to dilute the EU’s toughened China position.

Even while Macron supports the EU’s “de-risking” approach and anti-subsidies probes, Paris, keen to attract Chinese investment in its own EV sector, has emphasised Europe’s need to rebalance trade ties with China.

In contrast to France, where China’s wider relationship with Europe was the focus, the next two stops on Xi’s tour were Serbia and Hungary, both pro-China forces in Europe, where Beijing’s ties with Moscow are no barrier to cooperation.

In Hungary, often referred to as China’s Trojan horse in the EU, Chinese investments, such as the €7.3 billion to construct an EV battery plant near Debrecen, have made Hungary the largest recipient of Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in the Central and Eastern European region. In 2023, Hungary received FDI worth €13 billion, out of which €7.6 billion came from China, and the country also hosts Huawei’s largest external supply centre. Ramping up ties with Hungary is important as Budapest gears up to take over the EU Council’s rotating presidency in July. As the Union’s serial disruptor, Budapest has often blocked critical EU statements on China relating to its actions in the South China Sea and Hong Kong. Capitalising on Hungary’s disenchantment with Brussels, an EU member state unequivocally in its favour is in China’s interest.

Xi’s stopover in EU candidate country Serbia was smartly timed to coincide with the 25th anniversary of the 1999 NATO bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade — an opportunity to highlight US-led NATO’s disruptive global impact. With 29 new agreements signed, the visit had the intended effect of deepening China-Serbia bilateral cooperation. Italy’s BRI exit has increased the strategic importance of the Western Balkans as a route to access EU markets. Chinese investment data posits €10.3 billion flowed into Serbia from 2009-2021, with bilateral trade increasing from $450 million in 2012 to $4 billion in 2023.

Implications for India

Xi’s Europe tour has highlighted Beijing’s standard gimmick of playing divide and rule in Europe. With op-eds featured in prominent Serbian and Hungarian media, Xi’s charm offensive may have worked to double down on China’s relationships with these two nations. Yet his efforts at damage control and stabilising relations with the wider continent may not have been as successful.

Instead, his obvious attempts to drive a wedge between EU member states and exploit their divisions is likely to cast darker shadows. For Beijing, a possible Trump return in the White House presents a rationale to woo Europe in anticipation of weakening transatlantic ties. Yet, China’s unwillingness to assuage the EU’s core concerns relating to trade and using its leverage on Russia constructively has done little to alter the continent’s hawkish stance. Instead, all Macron received was Xi’s promise to not impose pre-emptive retaliatory tariffs on French cognac. So long as EU member states continue to prioritise their bilateral relations with China, the EU’s China policy will remain strained.

China’s unwillingness to assuage the EU’s core concerns relating to trade and using its leverage on Russia constructively has done little to alter the continent’s hawkish stance.

European efforts to find a footing in China present opportunities for India, whose own ties with Europe have strengthened in recent times, not in the least due to the China factor that has lured India and the West into a strategic embrace. Economic pressures to de-risk and diversify from China have encouraged the continent to sharpen its gaze towards more “like-minded” partners like India to reshape supply chains. However, to emerge as a credible destination for the West’s China+1 strategy, a more conducive Indian business environment is needed. Positive steps such as Make in India, movement up the ease of doing business ladder, and widespread digitisation are already being taken.

Europe is undergoing momentous shifts in its economic, security, and foreign policies, combined with a recalibration of traditional ties with China, Russia and the US, and a steady gaze at the Indo-Pacific. As India navigates its own international chessboard, it would be useful to pay active attention and play its cards accordingly. This may include ramping up its economic engagement with Europe, but also undertaking a more constructive role in bringing Russia and Ukraine to the table to negotiate an end to a war, whose outcome is unlikely to be decided on the battlefield. As Europe closely scrutinises Vladimir Putin’s upcoming visit to Beijing, the last factor could tip the balance in India’s favour, given the centrality of the war in Europe’s calculus and Russia’s status as Europe’s primary threat.

This commentary originaly appeared in Financial Express.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Professor Harsh V. Pant is Vice President – Studies and Foreign Policy at Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi. He is a Professor of International Relations ...

Read More +

Shairee Malhotra is Associate Fellow, Europe with ORF’s Strategic Studies Programme. Her areas of work include Indian foreign policy with a focus on EU-India relations, ...

Read More +