-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Regions which are seamlessly connected for commerce tend to remain together. Like Xi, Modi views infrastructure as a “glue”. For Xi, it is a glue to foster Chinese hegemony over its near abroad. For Modi, it is a “glue” to bind the nation.

Prime Minister Modi and scores of democratically elected leaders, must envy Xi Jinping the President and “uncrowned emperor” of China. The serried rows of compliant and attentive members of the People’s Congress, seated, as if pinned, to identical red upholstery; displaying endless patience through Xi’s three and a half hour over-long, speech, without once dozing off or interrupting with a “point of order”. All this must seem like a dream to our leaders, used as they are, to rambunctious legislatures, more eager to speak — often all together — than to listen.

Clearly, China has something to be chuffed about. Its model of socialism with “Chinese characteristics” cut away the romantic nonsense of socialist collectivism and recognises that private enterprise and (less strongly) markets, create wealth, rather than good intentioned, tight, public-sector management. By combining private enterprise with a strong government and political stability, the Chinese model borrows the best from different ideologies. China gets an A for creating national wealth and for distributing it — poverty was down to just 2% in 2014 versus 21.2% in India (per World Bank definition $1.9 PPP (2011) per person per day).

But the jury is out on whether an authoritarian state can nurture citizen centric growth. How long can the iron hand of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) continue to rule China absolutely? Will the Chinese middle class not replicate the autonomy and democracy movement of Hong Kong? These are current concerns. This much is evident, from the new Xi doctrine, spelt out on 18 October in Beijing, which espouses that the CCP must provide for the “happiness” of citizens; remain closely in touch with their aspirations and monitor citizens perceptions better.

China’s tiny, neighbour, Bhutan could teach China a lesson or two on whether “happiness” mixes well with absolutism. King Jigme Singye Wangchuck voluntarily abdicated in 2006, in the hope, that this would help Bhutan evolve into a modern, egalitarian, democratic country, whilst retaining its trade mark of happiness. The Bhutan constitutional monarchy is revered, like the British monarchy, which is widely respected and admired.

The Chinese quest for a prosperous, satisfied and happy populace living under the hegemony and parental control of the CCP, is self-defeating. The spirit of liberty and competition is not divisible. A market-led economy cannot be sustained under monopolised political power. Where markets rule, they drive the political process. Where the state rules it drives business. Innovation does not thrive in ecosystems, where the freedom of thought is absent. China is much admired as the factory of the world. But it has grown because worker rights do not exist, access to legal rights is limited and public interest is expected to mirror the CCPs interest.

Unlike China, India is determinedly heterogenous and multiparty. It lends itself to decentralised, democratic governance. It is tempting to infer, therefore, that India illustrates the value of democracy even in a poor, developing country. The recent Pew survey showed that 85% of Indians trust the government, even though, 40% of the population is vulnerable to poverty; governments have been negligent in providing public services and human development indicators are worse than in sub-Saharan Africa. But, disturbingly, the very same Pew Survey also shows that 55% of citizens are comfortable with a more autocratic, “strong” government.

This swing towards authoritarian governments is not isolated to India. It is an international trend in reaction to the economic limitations of the open economy, liberal, democratic model for development, particularly with respect to containing growing inequality. It is not surprising, therefore, that President Xi Jinping should advise developing countries to look closely at the Chinese model, which comes with dollops of loan assistance, as an alternative to the more standard western model of development, advocated by the multilateral financial institutions.

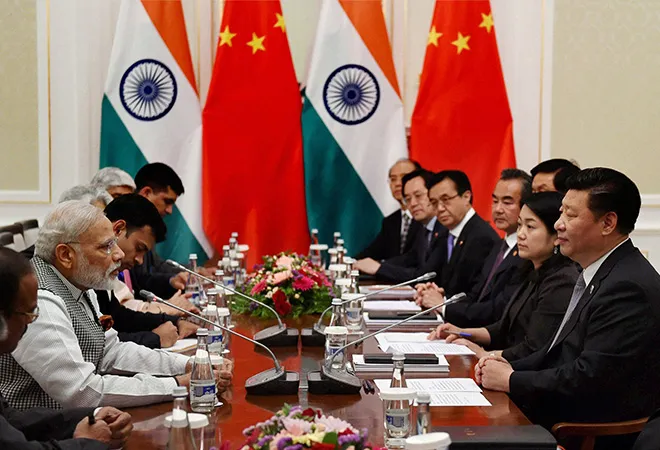

Prime Minister Modi was not just sharing dhoklas with President Xi in Ahmedabad way back in September 2014. There seems to have been a meeting of minds there. Like Modi’s vision of modernity, rooted in tradition, the Xi doctrine, also evokes the five thousand old civilisation of China. Both leaders focus heavily on external and domestic threats to security. Both advocate much stronger oversight of the media, the internet and educational institutions, to regulate disruptive dissent. Like Xi, Prime Minister Modi has used the first three years to implement structural reforms. His high decibel war on corruption is expected to minimise the financial “fire power” of the mafia; bridle political opposition and improve public sector outcomes. Implementation of the long-delayed Goods and Services tax (GST) shall, like Bollywood, bind us more tightly and provide incentives to integrate further. Regions which are seamlessly connected for commerce tend to remain together. Like Xi, Modi views infrastructure as a “glue”. For Xi, it is a glue to foster Chinese hegemony over its near abroad. For Modi, it is a “glue” to bind the nation.

The Xi doctrine seeks to realise the “China Dream” — a vision of a prosperous, environmentally clean country at the center of the world, contributing positively to mankind, by 2049 — the centenary of the founding of the Republic of China. There will be much to learn from China. But there are two immediate take-aways. First, that it is futile to copy the political systems of other countries mindlessly. Second, that even authoritarian governments need to listen to the people.

Indira Gandhi, turned away from absolutism and towards democracy, in 1977, by choosing to call for elections. This ended the two-year old national emergency. She gained personally and politically from this astute move. But it took an entire decade, till 1991, for the democratic apparatus to be used effectively, in public interest. We have not looked back since. India’s political architecture is finely tuned to the risk averse nature of its citizens. It charts the middle path to progress and shuns extreme options. China will do well to study this option closely, as it seeks pathways, for transforming from being a single minded, ruthlessly efficient, economic, power-house to a house, fostering happy Chinese.

This commentary originally appeared in The Times of India.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Sanjeev S. Ahluwalia has core skills in institutional analysis, energy and economic regulation and public financial management backed by eight years of project management experience ...

Read More +