The COVID-19 pandemic caused widespread disruptions to public transport systems around the world, as ridership fell to historic lows due to the severe restrictions imposed on travel to curb the spread of the virus. To relieve the economic stress precipitated by the transportation curbs, a staggered movement of goods, services and people was allowed. A public transportation network is considered resilient if it is able to transfer people to work and for their livelihoods and deliver services despite challenges and disruptions, whether it is something as predictable as inclement weather, or an unprecedented, global health crisis such as COVID-19.

The Global Public Transport Report 2020, compiled by the transit app and data business Moovit and released in January 2021, found that 70 percent of their respondents were wary of going back to pre-pandemic degree of public transport use. To return to using public transport, participants expressed a desire not only for more buses on the road to lessen the chances of vehicles being uncomfortably crowded, but also for easier access to data on how packed these vehicles are at different times. For example, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority developed a real-time crowding application during the initial year of the pandemic to help riders plan their trips by guiding them on how crowded the vehicles might get.

This shows that the use of public transport does not have to be reduced during times of crises, nor are people averse to using it as long as they have the information required.

A modal shift to private transport over fears of contracting the virus will aggravate poor air quality. Furthermore, those who cannot afford a shift to private transport and who rely on cheaper public transport options will be adversely affected—cutting off public transport will gravely impact the livelihoods of large sections of the population.

Although the pandemic has revealed the stresses to livelihoods, the economy and the environment when transport access is withdrawn, there are long-standing and persistent issues that impact its use, especially by women. A Thomson Reuters Foundation survey of 1,000 women in five global cities found that 52 percent of women reported that safety is their main concern while using public transport. In India, Safetipin’s report on women’s mobility in the cities of Bhopal, Gwalior and Jodhpur, found that 82 percent of the women regard overcrowding as the main reason they felt unsafe in public vehicles. Transport planning must consider that women’s concerns include both safety from the spread of diseases and safety from harassment.

Therefore, it is crucial to have safe and affordable public transport to achieve inclusive growth and bounce back to pre-pandemic normalcy. While restricting the number of people allowed to travel will limit the spread of the infection, these limitations will only exacerbate the existing shortage of multimodal public transport connections. According to a report for the National Centre for Biotechnology Information, cities like Mumbai already experienced a 20-percent shortage of public transport during evening peak hours prior to the pandemic, a figure that is expected to reach 25 percent when physical distancing measures are imposed.10 A report also shows that although India will need about 666,667 buses for its 25 million daily commuters, it currently only has around 25,000 in operation.11

Assessing the Impact of Safety Concerns on Women’s Mobility Choices

While the conversations on creating multimodal transport networks, modal splits and modal shifts will continue,12 this report is particularly interested in assessing the impact of Indian women’s safety concerns on their mobility choices. ‘Safety’ in this context means being protected from gender-based harassment, rather than safety from a virus. It refers to a woman’s level of comfort, ease and perception of risk during all stages of the journey and security from “intentional criminal or anti-social acts, including harassment, burglary, vandalism, while engaged in the journey.”

Women are less likely to participate in the workforce when their threat perception is high. As a substantial number of women use public transport to travel to work, insecurity and lack of safety in the mode of travel also curbs workforce participation.

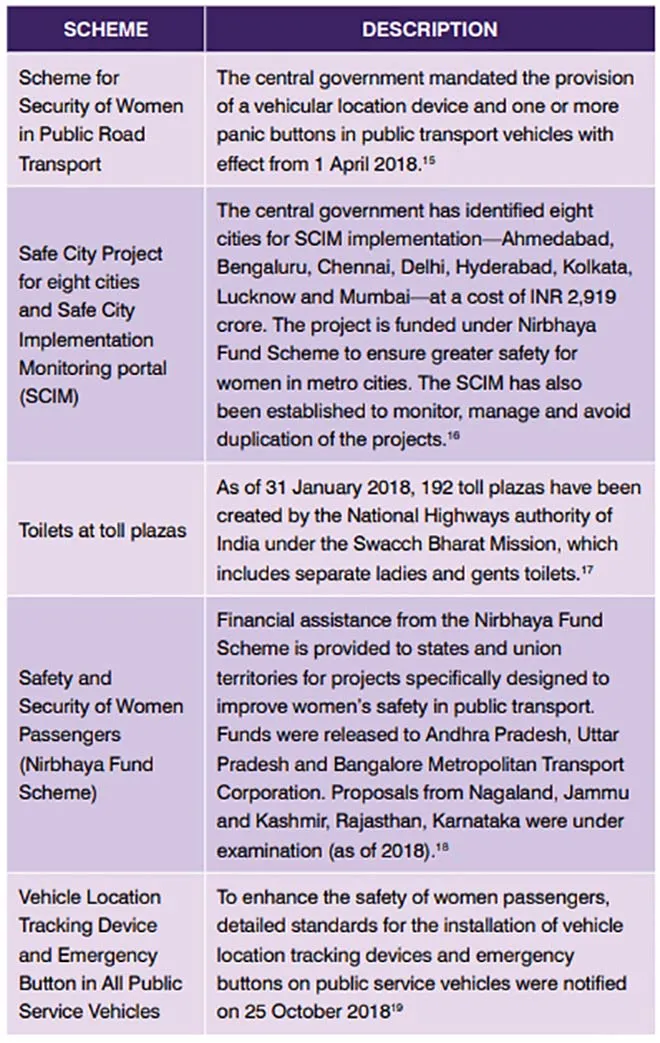

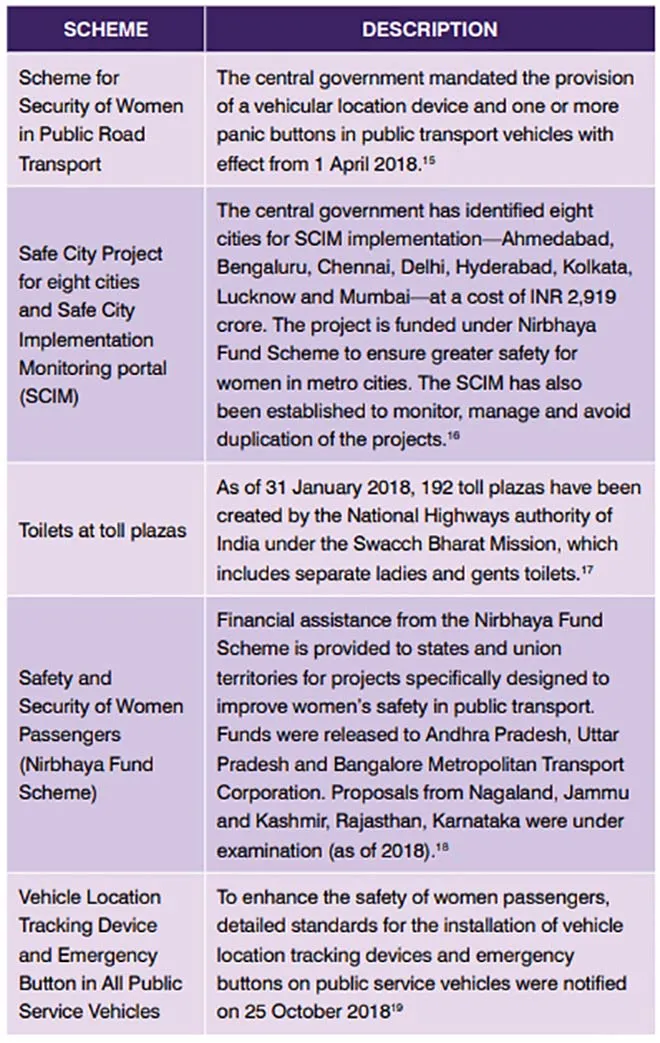

India has several national and state schemes attempting to create better and safer transport facilities for women (see Table 1)

The various measures on public transport need to integrate more gender elements. For example, the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT) strives to ensure that pollution is reduced by the increased use of public transport or by creating facilities for non-motorised transport (such as walking and cycling). It envisions urban transport to include ferry vessels for inland waterways (excluding ports/bay infrastructure) and buses, bus rapid transit system, footpaths/walkways, sidewalks, foot overbridges and facilities for non-motorised transport and multi-level parking. It also has a component on developing green spaces and parks with child-friendly facilities. However, apart from identifying women as beneficiaries, there is no particular focus on a gender-sensitive or participatory approach.

The Smart Cities Mission views efficient mobility and public transport and safety of women, children and the elderly as important components of the core infrastructure element of development. The policy aims to create walkable localities, reduce congestion, air pollution, and resource depletion, boost the local economy, and promote social interactions and security. It also aims to promote transit-oriented development, last-mile-para-transport connectivity, smart parking, intelligent traffic management, non-vehicle streets/zones, energy-efficient street lighting, and ensuring the safety of citizens (particularly women, children and the elderly). However, data on ways in which the security and safety for women can be enhanced is lacking. The present study aims to fill such gap about what women want and need to feel safe, depending on their types and preferences of transport.

The National Urban Policy Framework (NUPF) outlines an integrated and coherent framework towards the future of urban planning in India,24 with ten principles applied to ten functional areas of urban space and management:

1. Cities are structures of human capital

2. Cities require a sense of place

3. Cities are not static plans, but evolving ecosystems;

4. Cities are built for density

5. Public Spaces encourage social interactions;

6. Multimodal public transport system is the backbone

7. Environmental sustainability is key

8. Cities should grow to be financially self-reliant

9. Cities require clear unified leadership

10. Cities as engines of growth

The NUPF recognises that urban development is a state subject and that states need to develop their own urban policies and implementation plans based on this framework. States, therefore, need to integrate gender-sensitive planning into their frameworks.

Several cities have implemented schemes to increase safety in public transport (see Table 2).

The Rationale for a Survey and Report

India has introduced various policies to increase women’s safety while using public transport, but they are yet to be implemented efficiently. Safety concerns have an impact on a woman’s mobility preferences and choices. The purpose of the survey by the Observer Research Foundation (ORF) and Youth Ki Awaaz is to gauge the extent of this impact. Over ten months prior to and during the first year of the pandemic (December 2019 to September 2020), 4,262 women across 140 Indian cities were surveyed on their use of public transport, preferences of mode of transport, and safety concerns that impact these preferences. The findings were disaggregated by age, income, employment status, student status, residential status, and also the top 15 most populated metros versus other cities (based on Census 2011 data, as seen in Annex B).

An effort to decrease the number of people in vehicles to initiate social distancing leads to an increase in the number of people waiting at public transport platforms, resulting in congestion and risks to safety. Factors like congestion have been considered in the survey questions, and the results illustrate that policymakers must account for this in post-pandemic transport planning decision-making. Although several cities and states have incorporated measures to increase women’s safety during commuting, the survey results show that most women continue to feel the need to feel safer. This report describes the ways whereby Indian cities can achieve this.

Read the full report here.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV