-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Sunaina Kumar, “The Skilling Imperative in India: The Bridge Between Women and Work,” ORF Issue Brief No. 529, March 2022, Observer Research Foundation.

Introduction

Over the past decades, Indian women have been dropping out or being pushed out of the workforce at an alarming rate. This, amidst economic growth, urbanisation, a steady increase in women’s literacy, and an overall decline in fertility rates.

Data from the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) (2019-20) shows female labour force participation at 22.8 percent, compared to a far higher 56.8 percent for men.[1] The survey was conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic, which since 2020 has caused the further shrinking of the country’s female workforce. Data from PLFS for the quarter of January-March 2021 shows that women’s presence in the workforce dropped to 16.9 percent following the first year of the pandemic, while for men it remained largely the same.[2]

The pandemic has made it clear that India would need to bring its missing women to the workforce. Skilling has been touted as a solution. Indeed, skilling is aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) related to decent work and gender equality. In 2015 the Union government launched the National Skill Development Mission, which in its policy document emphasises that women constitute half the demographic dividend and skilling could be the key to increasing their participation in the country’s labour force.

To be sure, there is no single policy measure that can address the complex issue of women’s participation in the workforce. However, skilling can provide women with occupational choices and expand their work opportunities. Studies have shown that skilling has a proven impact on workforce participation.[3] Women in India who have attended skills training programmes, whether formal or informal, are more likely to be in the workforce, regardless of educational levels.

This brief gathers evidence to analyse the participation of women in skills training programmes. It examines the biases that lead to skilling women in jobs based on traditional societal constructions about what constitutes “women’s work”. As skilling programmes struggle to recruit and retain women in training courses and in employment,[4] the brief notes how skilling must be gender-sensitive and aware of the restrictive social norms for women. Skilling needs to keep pace with the transformations of the digital age and the future of work—factors which have only deepened the gendered digital divide. Public-private partnerships present a way forward to overcoming the skilling conundrum.

An Informal Female Workforce and the Challenge of Skilling

India has an acute shortage of skilled workers. From 2009, when the National Policy on Skill Development was formulated, there has been concerted support for policy-backed skill development initiatives. In recent years, there has been greater recognition of the need for skilling, and the Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship (MSDE) has launched several programmes. The aim of these initiatives is to prepare a highly-skilled workforce to address the needs of a burgeoning working-age population.

In 2015, the National Policy for Skill Development set a target to skill 402.87 million adults by 2022.[5] The challenge is daunting — after all, only 4.69 percent[6] of India’s total workforce have undergone any formal skills training. Other countries have far higher proportions of their populations undergoing skills training: 68 percent in the UK; 75 percent in Germany; 52 percent in the US; 80 percent in Japan; and 96 percent in South Korea.[7]

In India, the skilling of women is a far greater challenge than skilling men owing to the nature of women’s work. Most women in India are employed in low-skill and low-paying work, with neither social protection nor job security. Their economic contribution is all but made invisible. Globally, the informal economy employs more men (63 percent) than women (58.1 percent).[8] In India, however, a higher percentage of women workers are part of the informal economy compared to men — 94 percent of women workers are in the informal sectors, working as daily-wage agricultural labourers, at construction sites, as self-employed micro-entrepreneurs, or engaged in home-based work. Gender discrimination is more severe in the informal sector than in the formal sector, with women informal workers receiving less than half the male wage rate.[9]

India is trapped in a vicious cycle when it comes to skilling its informal workforce, according to a 2018 report[10] by the National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER). Greater informality leads to lower incentives to acquire new skills, while employers prefer machinery over labour when faced with inadequately skilled workers. Thus, few new jobs are created, driving India’s workforce further into informality. In the case of the female workforce, pervading informality is added to other challenges that keep them from participating in work – such as the burdens of family and caregiving, restrictive social norms, and limitations on mobility.

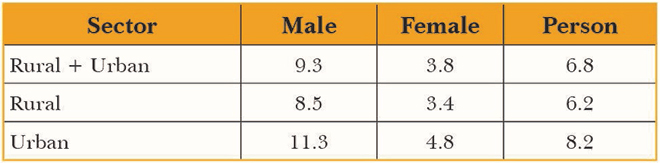

The inescapable gender gap shows up in skills training. According to Labour Bureau data from 2013-14,[11] only 3.8 percent of India’s adult women had ever received vocational training at that time, compared to 9.3 percent of men. Of these women who did receive vocational training, 39 percent did not join the labour force following training.

Table 1. Distribution of Persons 15 Years and Above Who Received Vocational Training (2013-14, in %)

Women’s Participation in Skills Training Programmes

To bridge the gap in skilling, various provisions have been made for women in skilling programmes. For instance, 30 percent of seats in Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs) are reserved for women. There are 15,042 such ITIs across the country. There are also a few exclusive National Skill Training Institutes for Women, which offer trainings under two schemes: the Craftsmen Training Scheme (CTS) and the Craft Instructors’ Training Scheme (CITS). Eleven such institutes have been set up and eight more are in the pipeline.

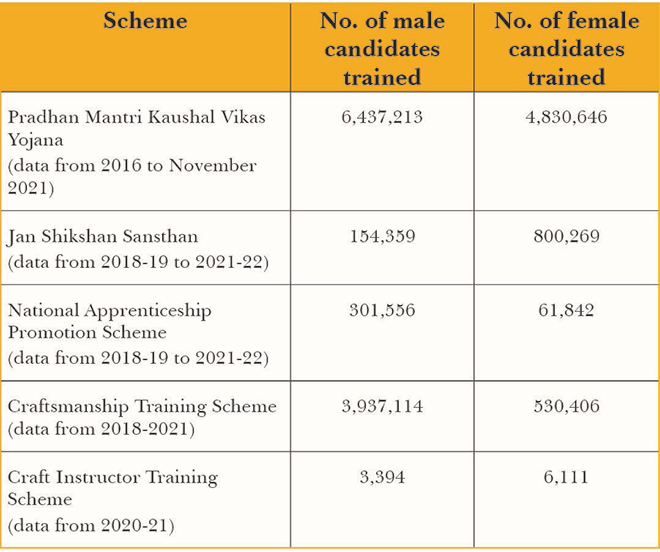

The flagship programme of MDSE—the Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PMKVY) which offers short-term skills training—pays close attention to the gender mainstreaming of skills. Close to 50 percent of candidates under PMKVY are women. The PMKVY is in its third phase and has trained 4,830,646 women as of November 2021. In 2021, the government commissioned a tracer study to look at the employment outcomes of women candidates who completed short-term skills training programmes under PMKVY. The results were yet to be released at the time of writing this brief.

The Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Grameen Kaushal Yojana (DDU-GKY), a placement-linked skills development programme for rural youth implemented by the Ministry of Rural Development, provides for a 33-percent reservation for women. DDU-GKY has trained 1,128,301 candidates so far, and about half the beneficiaries of the programme have been placed in jobs after obtaining their certification.[12]

Meanwhile, the Skills Acquisition and Knowledge Awareness for Livelihood Promotion (SANKALP) scheme, implemented by MSDE in collaboration with the World Bank, has targets to increase the participation of women in short-term vocational training. It is a supporting programme to skill training schemes like PMKVY. For its part, the Support to Training and Employment Programme for Women (STEP), launched in 1986 and implemented by the Ministry of Women and Child Development, is the oldest skilling scheme in India. It trains women to become self-employed or entrepreneurs. The scheme has become largely ineffective, though, with its budget remaining underutilised. In 2013-14, STEP’s budget was INR 180 million, of which around INR 70 million was used. By 2017-18, though its allocation was raised to INR 400 million, less than INR 25 million was utilised. The beneficiaries reduced from 31,478 to 4,200 in the same period.[13]

The National Apprenticeship Promotion Scheme (NAPS), launched in 2016, follows the apprenticeship model for skilling and placement. It links courses under PMKVY and DDU-GKY with apprenticeship training to prepare candidates for the job market. The scheme had a placement record of 44 percent, according to a 2018 Standing Committee Report on Labour. An evaluation by consulting firm Quantum Hub in 2020, however, noted that NAPS does not make any special provisions for female apprentices, such as safety at the workplace, or providing them gender-friendly infrastructure.[14]

The Jan Shikshan Sansthan, an old scheme under the Ministry of Human Resources Development,[15] has since been revived under the MSDE. It focuses on skilling non-literate and school dropouts, especially women.

Table 2. Women’s Participation in Skills Training Programmes

The Biases in Skilling Programmes for Women

Skills training programmes in India have historically been based on traditional gender roles and notions of women’s work, mostly restricted to household-related tasks and caregiving.[17] Though policies like ‘Skill India’ acknowledge the need for non-traditional occupations for women, they go little beyond rhetoric and the absorption of women into other sectors remains low. Courses for women under PMKVY, for instance, have concentrated on areas like apparel, beauty, wellness, and healthcare—this keeps women out of more remunerative sectors.

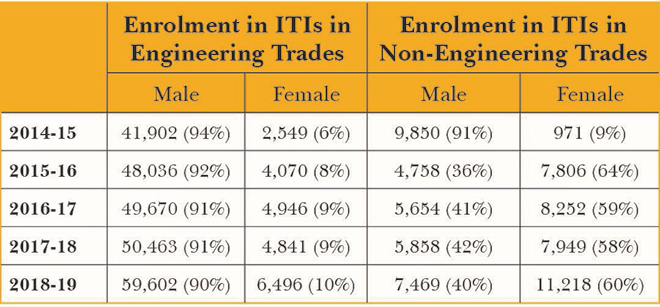

The National Skill Training Institutes for women offer only 21 courses, while the general ITIs, where men predominate, offer 153. Even among the 21, there is a preponderance of courses in occupations that are either outdated or patently stereotypical for women, such as secretarial practice, cosmetology, fashion design, or interior design. In the general ITIs, female enrolment is still low, though it has grown from 6 percent in 2014 to 21 percent in 2018[18].

A study of female participation in skills training—which gathered data between 2014 and 2018—found that enrolment of women in ITIs was concentrated in occupations such as dressmaking, computer operating, or surface ornamentation (part of fashion designing); less than 5 percent was enrolled in engineering-related courses.[19] Only 37 percent of female enrolments between 2014 and 2018 were in the priority sectors identified by the MSDE—i.e., those expected to generate the maximum jobs in the future. There were hardly any women taking courses in sectors such as construction and real estate, transportation and logistics, electronics, IT hardware, the auto industry, or the pharma industry.

The study asked the respondents why they chose the subjects they did. Their answers repeatedly brought up the perception around “trades considered suitable for females by society and family.” Even the dropout rate for females, at an average of 23 percent across ITIs, has been a matter of concern. Gender bias norms around work, mobility, information, and access to networks have affected the uptake of the programmes. Women cited multiple challenges they faced while undertaking vocational training: travelling to the remote locations of ITIs; absence of adequate, functional toilets at the institutes; lack of counselling and orientation for course selection; difficulties in dealing with course work alongside family responsibilities; and the perception of ITIs as male-dominated, with many more male instructors than female.

Table 3. Enrolment Across Engineering and Non-Engineering Trades, by Gender (2014-18)

This lack of diversity in skills training reflects the gender segregation of the job market. According to a 2018 study that looked at the National Sample Survey Office data from 1993-94 to 2011-12, gender representation in occupations in middle-skill segments has not changed markedly, despite a substantial presence of women workers in them.[21] Relatively little fresh employment has been created within high-skilled occupations, while there have been large, absolute increases in employment in unskilled occupations.

The government and private industry have revealed their limitations in overcoming gender disparities in skilling. However, a number of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have, to some extent, filled the gap. They train women in jobs that help break stereotypes, thus giving them access to livelihoods that have been traditionally male-dominated, enabling them to earn more than in the jobs traditionally assigned to them (such as domestic service and caregiving).[22] Studies have shown that women are keen on accessing non-traditional opportunities, and are confident of their capabilities.[23]

There are a few successful initiatives by NGOs in training women for non-traditional jobs and connecting them to the job market. They include Azad Foundation’s Women on Wheels, where women are trained in professional driving; the Self Employed Women’s Association’s (SEWA) Karmika School for Construction Workers in Gujarat; the Archana Women’s Centre in Kerala which trains women in masonry, carpentry, electrical work and plumbing; and the Barefoot College International’s Enriche Programme in Rajasthan which trains women in digital literacy, STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) subjects and sustainable livelihoods like solar technology.

How Family Pressures and Reluctance to Migrate Inhibit Women

Programmes under ‘Skill India’, launched in 2015, have fallen short of expected outcomes. One of the reasons is paucity of funds. The budgetary allocation for skilling has remained modest, with a large sum directed towards PMKVY, leaving little for the other schemes. PMKVY received INR 2,613.24 crore in this year’s budget out of the INR 2,999 crore allocated for MSDE.[24] Despite receiving the maximum budgetary allocation, PMKVY has a poor placement record; moreover, many candidates are placed in poor quality jobs in the informal sector. Out of 348,000 candidates trained under PMKVY in 2020-21, only 16,321 were placed in jobs, according to the 2022 Economic Survey.[25]

The data does not indicate the placement rate for women separately, but evaluations suggest they would have been very few. Programmes under Skill India struggle to recruit women, place them in jobs, and retain them in those jobs after they have been placed.[26] A study by the International Growth Centre tracked female participants in Odisha who had completed training under DDU-GKY.[27] It identified two crucial factors that inhibit women from taking up and keeping jobs. Both these issues are dictated by social norms: The most widely reported reason was that their families did not give them permission. (In the case of men, jobs were mostly turned down because of dissatisfaction with the compensation offered.) Subsequently too, women who dropped out did so mainly due to family pressure, while men quit due to job-related discontent.

A bottom-up approach to skilling could lead to better results. Such a strategy involves using local self-help group leaders to identify women workers with supportive families, and providing these women with relevant information to encourage them to take up skilling.

Women also reported a reluctance to migrate. While female trainees were less likely both to receive job offers and accept them, the chances of them doing so was even lower if the jobs required them to move out of their place of residence. Families of female trainees expressed concern for the women’s safety when they were offered jobs outside their district or state. The demand for skilled workers is concentrated in cities, and men comprise over 80 percent of migrant workers in India. Providing migration support to women could improve skilling and employment outcomes.

Digitisation and Automation: Women Could Be Left Out of the Future of Work

India’s skilling programmes are struggling to keep up with the demands of a changing and dynamic employment market. The pandemic and the “new normal” have speeded up the adoption of digital technology, transformed the world of work, and upended the demands of the market. Skilling needs to cope with the transformations of the digital age.

In the new normal, there is a risk of women with limited or no access being excluded even further. The pandemic has amplified the gendered digital divide.[28] Indian women are 15 percent less likely than men to own a mobile phone, and 33 percent less likely to use mobile internet services. In 2020, only 25 percent of the total adult female population in India owned a smartphone, versus 41 percent of adult men. The divide is much worse for women in the rural regions. Gender norms dictate women’s use of a mobile phone within households, thus widening the already gendered digital divide.

Whether agriculture, services, or industry, all sectors of the economy are embracing automation in varying degrees. It is estimated that up to 12 million women in India could risk losing their jobs to automation by 2030.[29] While men, too, are at risk, women face a graver threat, given already existing barriers.

The annual India Skills Report, which analyses skill distribution and hiring patterns in the country, has emphasised re-engineering skilling for the digital age as the most important employability trend for 2022 and beyond.[30] The shift to the digital age is reflected in the hiring patterns among sectors. In 2018, banking, financial services and insurance (BFSI), and retail, were the top two sectors for hiring; in 2022, the top-tiered are internet businesses, software, hardware and IT, and pharma, along with BFSI. The report uses an aptitude test to measure employability, which indicated that women in India were more employable (51.44 percent) than men (45.97 percent). Yet fewer among them were hired. The report notes that women are a vast resource pool for industries and predicts that their presence in the workforce will improve, spurred by economic changes and positive hiring intent.

Public-private partnerships could be the way forward for inclusive digital skilling, especially for women. There are a few programmes already underway. Microsoft and the National Skill Development Corporation (NSDC), in a public-private partnership, train more than 100,000 underserved women in digital skills.[31] Among them, 20,000 women are from regions with the lowest female labour force participation rates.

SAP India and Microsoft have also launched a joint skilling programme, TechSaksham,[32] for 62,000 female students from underserved communities, to train them for technology-related careers. The programme has partnered with the All India Council for Technical Education’s (AICTE) Training and Learning Academy-(ATAL) and the collegiate education departments of states to support professional development of faculty at participating institutes. In the first year, the initiative will train 1,500 teachers, and each of them will be equipped to support over 40-50 students a year, in turn impacting 60,000 to 75,000 students. These programmes have taken off in the last two years, despite the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic—this shows both the extent of the challenge and the potential for participatory transition.

Conclusion

For skilling to be effective for women in India, its training design has to be gender-sensitive. Skilling must be made bottom-up and sustainable. It cannot be viewed in isolation from the gendered realities of the labour market and prevailing social norms. Policies have to be gender-responsive to address the issues of recruitment and retention of women. They must be linked to awareness measures, to market needs, and coupled with post-placement support and welfare amenities.[33]

Childcare is a leading barrier that prevents women from participating in skills training, according to the World Bank.[34] Childcare provisions can improve women’s participation in skilling programmes, along with safe transportation that addresses their mobility limitations. Skilling must integrate women into sectors that are dominated by men, which can help improve their incomes.

There is also a need to integrate life skills, such as communication ability, decision-making capacity and self-confidence, into skilling programmes. Although life skills are essential for both men and women, in a country like India, women who acquire foundational and technical skills, often flounder when it comes to having confidence in decision-making. SEWA has been an early adopter of models of skilling that help girls and women grow into independent, well-rounded, confident leaders.

Given the opportunity, many more women in India could join the workforce. An effective policy environment and support from the private sector can tackle the crisis.

Endnotes

[1] Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS), National Statistical Office, July 2019-June 2020.

[2] Quarterly Bulletin, Periodic Labour Force Survey, January-March 2021.

[3] Erin K. Fletcher, Rohini Pande, and Charity Troyer Moore, Women and Work in India: Descriptive Evidence and a Review of Potential Policies, Centre of International Development at Harvard Univeristy, December 2017.

[4] Charity Troyer Moore, Soledad Prillaman, “Making Skill India Work for Women,” April 26, 2019, Initiative for What Works to Advance Women and Girls in the Economy.

[5] National Policy for Skill Development and Entrepreneurship, Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship, 2015.

[6] Extrapolated based on formal skilling data for working-age population from NSSO (68th Round) 2011-12, Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship, National Policy for Skill Development and Entrepreneurship, 2015.

[7] Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship, National Policy for Skill Development and Entrepreneurship, 2015.

[8] Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A Statistical Picture, International Labour Office, 2018.

[9] Surbhi Singh, Srikanth Ravishanker and Sneha Pillai, Women and Work: How India Fared in 2020, The Quantum Hub, Initiative for What Works to Advance Women and Girls in the Economy, January 2021.

[10] Bornali Bhandari, Pallavi Choudhuri, Mousumi Bhattacharjee, Tulika Bhattacharya, Soumya Bhadury, Girish Bahal, Saurabh Bandyopadhyay, Ajaya Kumar Sahu, Praveen Rawat, Mridula Duggal, Rohini Sanyal, Jahnavi Prabhakar, Skilling India: No Time to Lose, October 2018.

[11] Ministry of Labour and Employment, Labour Bureau, Chandigarh, Education, Skill Development and Labour Force Volume III, 2013-14.

[12] Deen Dayal Upadhayaya Grameen Kaushal Yojana, Ministry of Rural Development.

[13]The Quantum Hub, “Women’s Economic Empowerment in India, Policy Landscape on Skill Development”, January 2020.

[14]The Quantum Hub, “Women’s Economic Empowerment in India, Policy Landscape on Skill Development”

[15] In 2020, it reverted to its old name, ‘Ministry of Education’.

[16] Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship, December 2021.

[17]Poulomi Pal, Sharmishtha Nanda, Srishty Anand, Sneha Sharma, and Subhalakshmi Nandi, Vikalp: Policy Report on Skilling and Non-Traditional Livelihoods, International Centre for Research on Women, 2020.

[18] Ernst & Young, Gender Study to Identify Constraints on Female Participation in Skill Training and Labour Market in India, 2019.

[19] Gender Study to Identify Constraints on Female Participation in Skill Training and Labour Market in India, 2019

[20] Sourced from Ernst & Young, Gender Study, 2019.

[21] Bidisha Mondal, Jayati Ghosh, Shiney Chakraborty and Sona Mitra, Women Workers in India, Centre for Sustainable Employment, Azim Premji University, March 2018.

[22] Krishna Menon, Rukmini Sen and Amrita Gupta, Making NTL Work for the Marginalised, Azad Foundation, 2019.

[23] Sujata Gothoskar, An Exploratory Review of Skills-Building Initiatives in India and Their Relation To Women’s and Girl’s Empowerment, December 2016.

[24] Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship.

[25] Prashant K Nanda, Skills Mission Underperforms on Training Placement Goals, August 4, 2021, Mint.

[26] Rohini Pande, “Get the Policies Right First: How to get India’s Women Into the Workforce,” March 17, 2017, Business Standard.

[27] Soledad Artiz Prillaman, Rohini Pande, and Charity Troyer Moore, How can Skill India Improve Outcomes for Female Trainees, International Growth Centre, February 2018.

[28] Mitali Nikore, Ishita Uppadhayay, “India’s Gendered Digital Divide: How the Absence of Digital Access is Leaving Women Behind,” August 22, 2021.

[29] Anu Madgavkar, James Manyika, Mekala Krishnan, Kweilin Ellingrud, Lareina Yee, Jonathan Woetzel, Michael Chui, Vivian Hunt and Sruti Balakrishnan, The Future of Women at Work: Transitions in the Age of Automation, McKinsey Global Institute, June 2019.

[30] India Skills Report, Re-engineering Education and Skilling, Building for the Future of Work, 2022.

[31] “NSDC, Microsoft to train 1 lakh underserved Indian women in digital skills,” The Indian Express, October 30, 2020.

[33] Rohit Kumar, Renjini Rajagopalan, Akshay Agarwal and Vanya Gupta, Women’s Economic Empowerment in India, Initiative for What Works to Advance Women and Girls in the Economy, March 2020.

[34] Kathleen Beegle, Eliana Rubiano-Matulevich, “Five Ways to Make Skills Training Work for Women”, September 22, 2020

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Sunaina Kumar is a Senior Fellow at ORF and Executive Director at Think20 India Secretariat. At ORF, she works with the Centre for New Economic ...

Read More +