Viewed from Beijing, the recent past of Sino-Indian relations have been somewhat disconcerting. In January of 2015 in New Delhi, President Obama and Prime Minister Modi signed on a “Joint Strategic Vision for Asia Pacific and the Indian Ocean” that now has the two sides discussing basing protocols and joint naval patrols.

Later, the Indian Prime Minister visited China and publicly called out Beijing “to reconsider its approach on some of the issues that hold us back from realising the full potential of our partnership,” bluntly pinning the blame for the state of Sino-Indian relations on China.

In recent months, the trend became more disturbing. First, New Delhi demanded that Beijing end its hold on declaring Masood Azhar a global terrorist. Then, it insistently urged China to support its application for full membership to the Nuclear Suppliers Group. And all this accompanied by a high-decibel media campaign. The ultimate poke-in-the-eye was the international conference, subsequently called off, involving a cross-section of Chinese dissidents, convened in, of all places, Dharamshala, the seat of the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan government-in-exile.

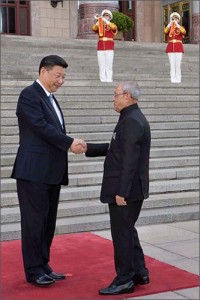

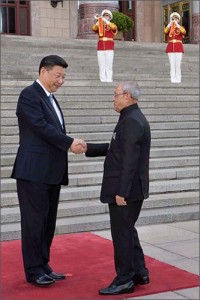

It is not surprising, then, that the < style="color: #000000;">primary objective of President Pranab Mukherjee’s four day visit to China last week was to calm the roiled atmosphere and reassure Beijing that New Delhi not only values its relationship with China, but seeks to enhance them. In the parlance of modern international relations, this is called “strategic communications”, and it is something the seasoned Mukherjee excels in. This was evident in the principal Chinese readout of the meetings in which Xi told Mukherjee that the two sides should “appropriately address our differences” and consolidate “political trust through high-level interactions.”

< style="color: #000000;">The key to Mukherjee’s visit were his several conversations < data-term="goog_667851290">on Thursday afternoon with the Chinese supremo Xi Jinping whose powers vie with those of the emperors of yore. It was just last month that Xi appeared in military fatigues and added the title of the Supreme Commander of the PLA to his existing ones as the general secretary of the Communist Party, head of state and chairman of the Central Military Commission.

Source: PTI

Source: PTI

Mukherjee is also the Supreme Commander of India’s military and head of state, but he is bound legally by the advice of his Council of Ministers. As President, Mukherjee does not get involved in the specific issues or negotiations; he’s been there and done it as a minister. But the man who has held every important portfolio in the government, except that of Prime Minister, is a vast trove of experience and is the closest thing to an elder statesman in our system. And so in his own words to the students and faculty at Peking University, his “enhanced political communication” with his Chinese counterparts sought to minimise the differences and maximise the developmental opportunities of the Sino-Indian relationship.

Not all issues can be taken up frontally in diplomacy. Some meet a straight bat, others are cut through the slips or swept through to fine leg or simply blocked; shrewd diplomacy means you don’t slog the ball to the boundary. So, some of the more tangled issues were discussed directly by Foreign Secretary Jaishankar in his call-on the Foreign Minister Wang Yi. In line with this, there was nothing in official readouts on the aborted conference of Chinese dissidents in Dharamshala or the Indian posture on the South China Seas issue.

In the official readout, the old perennial, the border dispute, was treated with the routine promise of fair and equitable resolution. But, the key was the reiteration by both sides in the official talks of their decision to keep a firm hold on their respective militaries and prevent border confrontations such as those that occurred in Depsang in 2013 and Chumur in 2014.

Mukherjee did not pitch his Masood Azhar ball straight; he spun it by seeking Chinese support in the context of the bilateral and global cooperation between the two countries in the fight against terrorism. And so, the Chinese agreed that terrorism was indeed a global menace and expressed their willingness to “enhance cooperation, including in the UN.” What happens when it comes up next before the ISIS-Al Qaeda sanctions committee in the UN is a matter of detail.

On the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) issue where China can blackball the Indian application of membership, Mukhejee did not kowtow. Instead, he sought Chinese cooperation in the context of India and China’s developmental partnership and climate change. India faced an acute energy shortage and nuclear energy had a key role in Indian plans. But this required a “predictable environment” in which civil nuclear trade could take place and so, New Delhi expected Beijing to play a “positive and facilitative role.”

The tone and tenor of the visit was intended to convey a sense of self-confidence and maturity of the two Asian giants in handling their difficult relationship. It was meant to signal their ability to deal directly with each other on difficult issues and thereby denying space to third parties for any gain. Beyond that, it was meant to show that the two huge neighbours were aware of their responsibility to play a stabilising role in a world which is in turmoil.

Our ties with China involve four c’s — competition, cooperation, conflict and containment. We need to become more competitive and cooperative and less inclined to conflict or containment strategies against each other. India has a great deal to gain from strong ties with China and a lot to lose otherwise. We need to carefully strategise ways and means of tapping Chinese investments and linking up to their supply chains to promote our manufacturing ambitions. At the same time, we need to be able to deter China from doing things against our interests.

This commentary originally appeared in The Times of India.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source: PTI

Source: PTI PREV

PREV