Two and a half years ago, the West African nation of Guinea made the headlines when its people took to the streets to celebrate the overthrow of President Alpha Condé on 5 September 2021. President Condé was an autocrat who had been ruling the country since 2010. The fall of Condé captivated interests across the continent, unnerving other despotic leaders of the region and ultimately paving the way for military takeovers in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger.

The fall of three democratically elected but unpopular leaders of Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger within a mere two and half years and the coming of the Junta governments underscores the long-held beliefs about the region’s political culture. Although there have been multiple coups in West Africa in the past, the region was relatively calm for nearly 20 years. Nonetheless, the abrupt upsurge in coups across the continent—which includes ones in Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, and Niger—raises concerns about the disintegration of a region, otherwise relatively well integrated.

The fall of Condé captivated interests across the continent, unnerving other despotic leaders of the region and ultimately paving the way for military takeovers in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger.

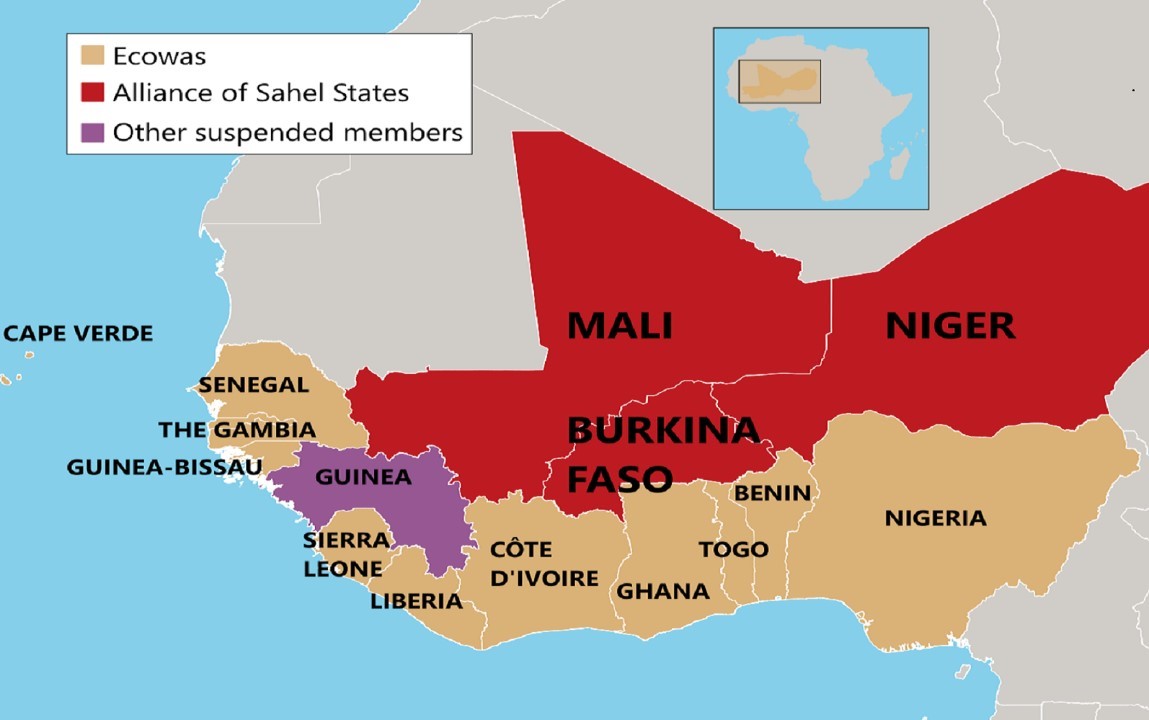

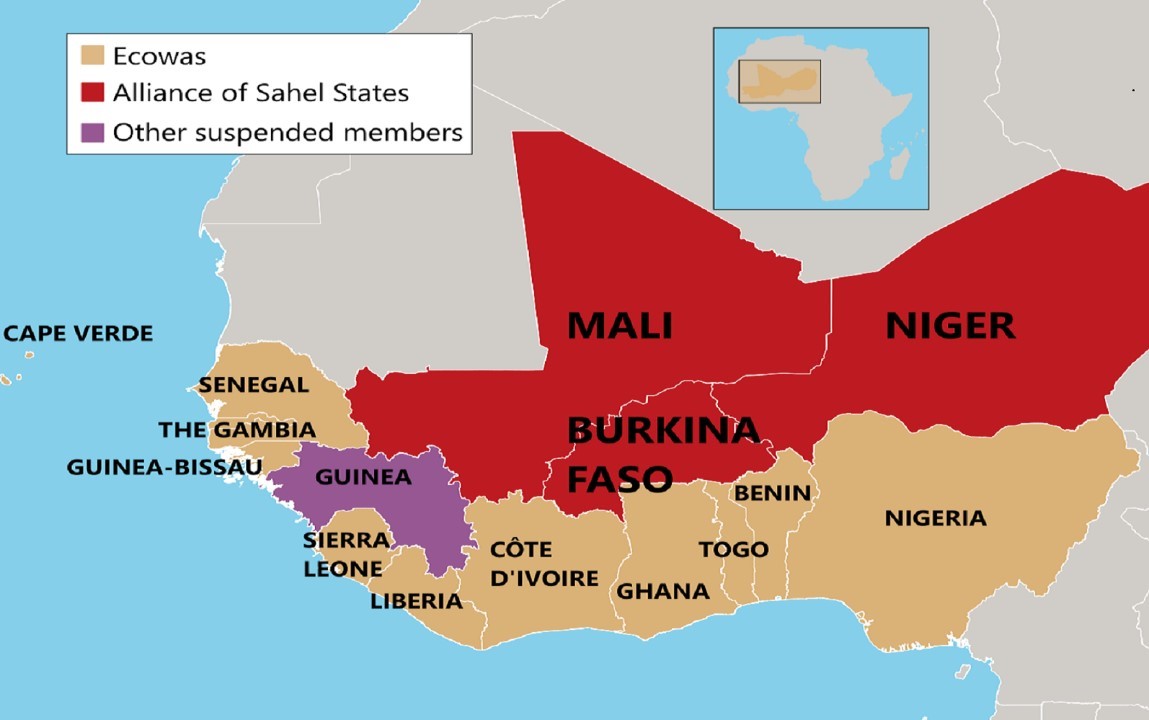

Furthermore, in September 2023, these three nations decided to leave their 15-member regional economic block, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), and establish the Alliance of Sahel States, also known as L’Alliance des États du Sahel (AES). The Alliance of Sahel States agreed in this mutual defence treaty to defend each other if any of them were attacked. The agreement also stipulates that the three countries cooperate to prevent any armed uprisings.

In international politics, drawing parallels has its own risks. Nonetheless, given the current state of affairs in Guinea, it is hard to ignore the similarities between Guinea’s development and that of the AES countries. Indeed, there’s a good chance Guinea, cornered by military threats and sanctions, may turn to the Junta coalition for protection. Further, as none of the three countries have direct access to the sea, having maritime access only strengthens Guinea’s acceptability in the grouping.

Image: Alliance of Sahel States and Guinea

Developments in Guinea

The West African nation of Guinea is well-endowed with natural resources. Guinea produces over 22 percent of the world’s bauxite, making it the second-largest producer worldwide. The nation also produces iron ore, diamonds, and gold. Guinea supplies 55 percent of China’s bauxite imports, making it the country’s largest supplier of the mineral. Yet, years of instability stemming have left Guinea one of the world’s poorest countries. Guinea had already witnessed two military coups before Condé was elected as the first democratic leader of the country in 2010. During the reign of both of the earlier Junta leaders Lansana Conté and Moussa Dadis Camara, in 1984 and 2008, respectively, drug trafficking and corruption of state finances were rampant.

As a matter of fact, following his two constitutionally permitted terms in office, President Condé was widely criticised because of widespread allegations of drug trafficking and misappropriation of public funds. Nevertheless, he went ahead with the constitutional amendment to enable him to seek the presidency more than twice. Therefore, when the military led by Colonel Mamady Doumbouya of Guinea’s Special Forces overthrew Condé’s government, the people of Guinea were quite gung-ho about the solid prospects for a robust and prosperous democracy.

Guinea supplies 55 percent of China’s bauxite imports, making it the country’s largest supplier of the mineral.

Predictably, during the post-coup announcements, Colonel Doumbouya aroused genuine patriotism. Following his ascension to power, Doumbouya claimed the coup served the interests of the Guinean people by toppling a president who was fixated on maintaining control at all costs. He also pledged a national consultation to facilitate a peaceful and inclusive transition. Additionally, he renamed his Junta the National Committee of Rally and Development (NCRD), sparking rumours that he was trying to pass himself off as a civilian candidate.

It would be unfair to claim that Doumbouya’s administration has accomplished nothing in its two-and-a-half years in office. A court was established to address the financial and economic offences that took place under Condé’s government. Many of Condé’s allies, who were being charged with corruption and embezzlement, were detained. It also made it easier for the trial of those responsible for the 28th September 2009 massacre at Conakry Stadium, which the United Nations (UN) designated as a crime against humanity. Additionally, Doumbouya also launched the construction of tangible infrastructure projects and national consultations.

But after two and a half years, optimism regarding democracy had faded to despair. In 2022, the Junta prohibited all protests and detained numerous Opposition figures, members of civil society, and journalists. There have been numerous restrictions on internet access. To make things worse, the transitional administration, which had been in power since July 2022, was disbanded by the Junta in February 2024. In addition, the Junta ordered an account freeze for all the transitional government members. Their travel documents were confiscated, and their service vehicles, bodyguards, and assistants were removed without any explanation. Although the public’s reaction to this dissolution is still unknown, it doesn’t appear to be a step in the right direction toward the democratic election that many Guineans were hoping for.

The Junta prohibited all protests and detained numerous Opposition figures, members of civil society, and journalists. There have been numerous restrictions on internet access.

The broader implications of events in Guinea

The Guinean situation offers crucial insights for international policymakers to comprehend why Guinea’s democratic experiment failed and what kinds of domestic and foreign assistance could help the country resume its transition to democracy. The current events in Guinea resemble Mali, a country beset by political instability after the military government’s inability to fulfil its obligations for a smooth handover to civilian authority. The Junta chose to postpone the presidential election and left the ECOWAS just one month before elections under the Transitional Sovereign Council were scheduled.

Unlike the three AES countries, Guinea seemed to be in capable hands. However, this new development may cause many to rethink and this could possibly lead to civil unrest. While political reform and eventual democratic transition are touted as the main goals of all coup leaders, historical evidence indicates that the military is not a reliable ally in the process of bringing about democracy. On the other hand, military intervention might potentially result in a democracy that stagnates, pushing the nation to revert to dictatorship.

The Junta chose to postpone the presidential election and left the ECOWAS just one month before elections under the Transitional Sovereign Council were scheduled.

Guinea is currently experiencing a severe economic crisis with nearly half the country’s population living in extreme poverty. Intertwined with the economic crisis, a fast-declining social order has actually smoothened Doumbouya’s power grab. Many experts attribute Africa’s subpar democratic and economic conditions to neocolonialism. This narrative would certainly benefit non-Western emerging nations like Iran, China, and Russia. Clearly, Russia would benefit the most from these developments. The Wagner Group, now rebranded as Africa Corps, and the Alliance of Sahel States, which Russia has already endorsed, could help Moscow establish its dominance over the region. Given that Russia and Guinea have historically had strong relationships, this could encourage and expedite Guinea’s decision to join the team AES.

The Gulf of Guinea accounts for over 35 percent of global petroleum reserves. The region is already engulfed in widespread pirate activities. Guinea’s joining the AES will increase further lawlessness in the region. From here, only two feasible options seem to be available to international actors: apply harsh economic sanctions, engage in military action or a combination of both. Yet, either of these measures could push the Junta to join the Alliance of Sahel States. There may be another course of action, a third choice: dialogue. Guinea’s transition to a democratic government framework will hinge on the effectiveness and sustainability of fostering true inclusivity through dialogues.

Samir Bhattacharya is an Associate Fellow with the Strategic Studies Programme at the Observer Research Foundation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV