-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Sohini Bose, Ed., “The Dynamics of Vaccine Diplomacy in India’s Neighbourhood,” ORF Special Report No. 145, June 2021, Observer Research Foundation.

Introduction

In early 2021, India—driven by its ‘Neighbourhood First’ policy[1] and in its understanding of its role as the ‘net security provider’ of the region—[2] began providing COVID-19 vaccines on a priority basis to its immediate neighbours.[a] Between January and April, India either sold or granted a total of 19,542,000 vaccine doses to countries in the region,[3] until it stopped further exports in late April when it became clear that the second wave of the pandemic was going to be far more severe than the first one in 2020. Today, at the time of writing this report, a significant volume of vaccines purchased from India by some of these near-neighbours remains undelivered. Moreover, the promise of the Quad countries[b] “to expand and accelerate production [of vaccines] in India” for the Indo-Pacific[4] remains unfulfilled. India’s neighbours have thus been compelled to find alternative sources for their vaccine requirements. Seeing an opportunity to exert their soft power while helping mitigate a humanitarian crisis, China and Russia are filling the gaps.

This special report examines the dynamics of vaccine diplomacy in India’s neighbourhood. In five sections, the report explores the state of the countries’ vaccine rollout, the gaps in supply that either China or Russia is bridging as India halted vaccine supply, and the implications of such efforts on the bigger geostrategic picture across India’s near-neighbourhood.

In her essay on Bangladesh—often referred to as India’s “closest alliance” in the neighbourhood,[5] Sohini Bose highlights the diplomatic challenges it faces in balancing the strategic underpinnings of the vaccine assistance it receives. Sohini Nayak focuses on the Himalayan countries in India’s northern neighbourhood, especially Nepal and its desperate search for vaccines, and Bhutan’s composure as it prepares to provide assistance to India. In the third piece, on India’s Southeast Asian neighbours, Sreeparna Banerjee illustrates the domestic turmoil in Myanmar and the challenges facing Thailand’s government as the country suffers vaccine shortages, and China’s assistance to both countries. Bringing perspectives of the island nations in India’s southern neighbourhood, Vinitha Revi discusses how Sri Lanka and Maldives are faring in their quest for alternative sources of vaccines. Lastly, pondering the situation in India’s western front, Saaransh Mishra explores how the dearth of vaccines in Afghanistan gives interested powers an opportunity to gain a foothold in the country; he outlines the strategic stance of Pakistan, as the only country in India’s near-neighbourhood to not have been a recipient of India’s vaccine outreach.

[a] This report uses the word ‘neighbourhood’ or ‘region’ to refer to these countries: Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, Myanmar, Thailand, Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

[b] The Quad is a grouping of India, the US, Australia and Japan, aimed at maintaining a rules-based order, and a free, open and inclusive Indo-Pacific, as a force for ‘global good’.

[1] Government of India, “Question No.3692 Neighbourhood First Policy,” Media Center, Ministry of External Affairs, July 25, 2019.

[2]David Brewster, “India: Regional net security provider,” Media Center, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, November 05, 2013.

[3]Government of India, “Vaccine Supply,” Ministry of External Affairs, May 29, 2021.

[4] Joe Biden, Narendra Modi, Scott Morrison and Yoshihide Suga, “Our four nations are committed to a free, open, secure and prosperous Indo-Pacific region,” The Washington Post, March 13, 2021.

[5] Subir Bhaumik, “Made for each other: Bangladesh is evolving into India’s best friend in the neighbourhood,” The Times of India, March 18, 2021.

Bangladesh: Navigating Diplomacy Challenges in Search for Vaccines

Sohini Bose

On 26 April 2021, Bangladesh sealed its borders with India to contain the spread of the B.1.617.2 variant of the B.1.617 strain of the novel coronavirus, first identified in Maharashtra and among the reasons experts say the country plunged into a massive second wave of the pandemic beginning in April.[1] Despite precautions, including successive nation-wide lockdowns, Bangladesh is recording 1,646 new cases on an average every day in the seven days prior to the writing of this piece.[2] In desperate need for vaccines, Bangladesh has turned to a number of countries for assistance.

Only some months earlier, in October 2020, the Sheikh Hasina government had declined China’s offer of its CoronaVac vaccine, doubting its efficacy and because the purchase would have involved a clause on sharing the cost of clinical trials.[3] Bangladesh turned to India, which accounts for 60 percent of global vaccine production[4] and is known as Bangladesh’s “all-weather ally”.[5] The two countries share civilisational links, and the Joint Statement issued during the visit of the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to Bangladesh in March 2021, describes this partnership of half a century as a “model of bilateral ties for the entire region.”[6] For India, Bangladesh is a focal point in its ‘Neighbourhood First’ policy.[7] However, India’s reason to respond with alacrity to Bangladesh’s request for vaccines is about not only this, but also the Indian government’s desire to improve the country’s image in the eyes of the Bangladeshi people.

In the past few years, public opinion about India in Bangladesh has suffered following the former’s adoption of policies that have ramifications to the Islamic community in India.[8] The central government’s revocation of the special status of Jammu and Kashmir in August 2019, and the accompanying decisions to detain political leaders and restrict communication, were hugely unpopular in Muslim-majority Bangladesh.[9] In January 2020, India adopted the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) which grants Indian citizenship to persecuted non-Muslims from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh, and the National Register of Citizens was set to be implemented to identify illegal Bangladeshi migrants living in Assam. These triggered protests from many forums in Bangladesh.[10] Another setback has been the long-drawn failure to sign the Teesta River water agreement, which if finalised would clarify the sharing of this essential waterway that straddles India and Bangladesh.[11] To be sure, the Hasina government remains keen to maintain favourable ties with India.

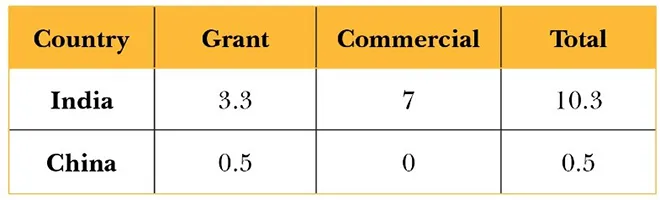

Vaccine diplomacy offered India the opportunity to not only strengthen its relations with the Bangladesh government but also to win back the goodwill of its people. It is therefore no surprise that Bangladesh was the first country to receive vaccines from India, under its ‘Vaccine Maitri’ initiative. In January 2021, India gifted Bangladesh some 3.3 million Covishield vaccine doses manufactured by the Serum Institute of India (SII) in Pune. This was followed by a dispatch of another 7 million vaccine doses, this time purchased by Bangladesh, and also from SII. At the time of writing, India has supplied 10.3 million vaccine doses to Bangladesh—the highest volume amongst the 93 countries which have so far received vaccines from India.[12]

However, the outbreak of the second wave of the pandemic in India and the resultant decision to halt all vaccine exports created circumstances little anticipated by either country. As the promised consignment of 5 million doses from the total of 30 million it had purchased[13] remained undelivered,[a],[14] Bangladesh’s anxious search for alternative sources led it to China. Beijing has been increasingly working on cultivating closer ties with Dhaka to secure its foothold in the Indian Ocean Region and leverage its flagship Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).[15] Capitalising on the urgency, Chinese vaccine manufacturer Sinopharm gifted 500,000 doses to Bangladesh on 12 May 2021. The assistance follows China’s ambassador to Bangladesh, Li Jimming’s warning to Bangladesh that bilateral ties would be damaged if it joined the Quad alliance,[b],[16] which it deems to be an anti-Beijing “club” and in which India is a member.[17] Earlier, in April, China’s Minister of Defense Wei Fenghe visited Bangladesh and called for enhanced military cooperation to prevent external powers from setting up a “military alliance in South Asia.”[18]

Table 1: Vaccines received by Bangladesh from India and China (in million doses)

[caption id="attachment_87986" align="aligncenter" width="660"] Sources: Government and media reports.[19][/caption]

Sources: Government and media reports.[19][/caption]

Such statements carry a coercive undertone to vaccine diplomacy in Bangladesh and corresponds with India’s apprehensions that China is trying to make inroads into its neighbourhood to counter its pre-eminence.[20] As a small developing country situated in close proximity to these two Asian powers, Bangladesh has long aimed to maintain meaningful partnerships with both while safeguarding its sovereignty. The remarks from China’s envoy thus provoked a strong response from the Bangladeshi Foreign Minister, who reasserted the country’s sovereignty to make independent decisions about its foreign policy.[21] Nonetheless, Bangladesh plans to purchase 40 to 50 million vaccine doses more from China, along with proposing to co-produce, if the latter agrees.[22]

Bangladesh is aware, though, that it needs to diversify its sources of vaccines. The country has thus approved the emergency use of Russia’s Sputnik V by end-April and four million doses were scheduled to arrive in May.[23] At the time of writing, however, the vaccines are yet to be received. The US, the UK and Canada have already been contacted to secure some 3.5 million doses of the Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine as emergency shipments.[24] As of 5 June 2021, only 2.6 percent of Bangladesh’s entire population have been fully vaccinated and only 3.6 percent have received their first dose.[25]

The present situation in Bangladesh is a test of the government’s diplomacy skills. On one hand, it is honouring its bilateral ties with India, providing assistance of 10,000 vials of Remdesivir injections, 30,000 PPE kits, and 2,672 boxes of medicines.[26] At the same time, Bangladesh has an undeniable dependence on China—its largest trading partner,[27] and now its sole provider of COVID-19 vaccines. In order to sustain its bilateral ties with both India and China, while also safeguarding its sovereignty, Bangladesh should keep the reins of vaccine diplomacy in its own hands. Managed well, it will help in alleviating its present crisis; gone wrong, it will entangle Bangladesh in power politics.

[a] There has been no official response from India in this regard.

[b]The Quad is a loose-knit strategic network of four democracies; India, USA, Australia and Japan aimed at maintaining a rules-based order, and a free, open and inclusive Indo-Pacific, as a force for ‘global good’.

[1] Saikiran Kannan, “Of SARS and SAARC: Fear of Covid mutant looms over South Asia,” India Today, June 02, 2021.

[2] “Bangladesh,” Covid 19 Tracker Reuters, June 5, 2021.

[3] Shishir Gupta, “Dhaka turned to India for vaccine after China wanted Bangladesh to share clinical trials' cost,” Hindustan Times, January 24, 2021.

[4] Srividhya, Sanya Datt and Ankita Sharma, “India: Pharmacy to the World,” Invest India, July 31, 2020.

[5] Himanshu Sharma, “The all-weather Indo-Bangladesh friendship,” New Delhi Times, February 01, 2021.

[6]Government of India, “Joint Statement issued on the occasion of the visit of Prime Minister of India to Bangladesh,” Media Center, Ministry of External Affairs, March 27, 2021.

[7] Government of India, “Question No.3692 Neighbourhood First Policy,” Media Center, Ministry of External Affairs, July 25, 2019.

[8] “As Bangladesh’s relations with India weaken, ties with China strengthen,” The Economist, September 17, 2020.

[9] Kazl Abedur Rahman, “India-Bangladesh Relations: The China Factor,” International Policy Digest, September 17, 2020.

[10] “Bangladeshi forum rallies in protest of Indian NRC-CAA,” The Dhaka Tribune, December 20, 2019.

[11] Archana Chaudhary and Arun Devnath, “India seeks to mend Bangladesh ties with coronavirus vaccine diplomacy,” Business Standard, December 17, 2020.

[12]Government of India, “Vaccine Supply,” Ministry of External Affairs, May 29, 2021.

[13] “Bangladesh eyes Sputnik vaccine to overcome supply shortage from India,” Hindustan Times, April 20, 2021.

[14]Government of India, “Joint Statement issued on the occasion of the visit of Prime Minister of India to Bangladesh,” op. cit.

[15] Kazl Abedur Rahman, op. cit.

[16]For more information on Quad see, Sumitha Narayanan Kutty and Rajesh Basrur, “The Quad: What It Is – And What It Is Not,” The Diplomat, March 24, 2021.

[17]“Bangladesh receives 5,00,000 doses of Chinese COVID-19 vaccine as gift,” The Hindu, May 12, 2021.

[18]“Bangladesh, China agree to increase military cooperation,” Xinhuanet, April 27, 2021.

[19]For India see Government of India, “Vaccine Supply,” op. cit. For China see, “Bangladesh receives 5,00,000 doses of Chinese COVID-19 vaccine as gift,” op.cit.

[20] Smruti S. Pattanaik, “The Geopolitics of Power Configuration in South Asia: Understanding Chinese Defence Minister’s Visit to Bangladesh and Sri Lanka,” IDSA, June 02, 2021.

[21] Ananth Krishnan, “Bangladesh rebuffs China on Quad warning,” The Hindu, May 12, 2021.

[22]“Bangladesh receives 5,00,000 doses of Chinese COVID-19 vaccine as gift,” The Hindu, May 12, 2021.

[23]“Bangladesh approves Russia's Sputnik V Covid-19 vaccine for emergency use,” Hindustan Times, April 28, 2021.

[24]SM Najmus Sakib, “Bangladesh says COVID-19 vaccines to run out in 1 week,” AA, May 23, 2021.

[25]“Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations,” Our World in Data, May 29, 2021.

[26]“Partnerships of Hope: Bangladesh contributes to supporting India to fight Covid-19,” Invest India, May 21, 2021.

[27] Joyeeta Bhattacharjee, “Bangladesh: Zero-tariff imports, a diplomatic victory for China,” Observer Research Foundation, July 09, 2020.

Nepal and Bhutan: Mountains of Challenges in the Himalayan States

Sohini Nayak

The Himalayan countries of Nepal and Bhutan have not been spared the cruel COVID-19 pandemic, with cases surging since the end of March 2021. Grappling with a sharp rise in infections and deaths, both countries’ already-fragile health infrastructures are overwhelmed: there is a lack of comprehensive medical facilities, hospitals are filled to capacity, and critical medical supplies are absent.[1] To be sure, Bhutan is still able to manage, better than Nepal. The Ministry of Health and Population of Nepal issued a statement in April 2021 acknowledging the gravity of the situation in the country, and announcing a lockdown as well as restrictions on gatherings. According to data from the World Health Organization (WHO), there was an 88.6-percent increase in new cases in the country between the short period of 5 to 11 April—the peak of the second wave.[2] By May, the situation has only marginally improved. Between 17 to 23 May, 77 percent of all new cases across Nepal were recorded from only three provinces: Bagmati, Lumbini, and Biratnagar. There was a 3-percent overall decline in the country’s new cases in May. The test positivity rate also dropped, but still remained high at 39 percent, in comparison to the other south Asian countries.[3]

In the Kingdom of Bhutan, between April and May 2021, there was a 66.2-percent increase in daily cases, primarily in Phuentsholing that borders India, as well as in Samdrup Jongkhar and Trashigang districts.[4] At the time of writing this report, there were only 1,620 confirmed cases across the country, eight new cases, and one death.[5] Most of the dzongkhag (districts) have been under complete lockdown, with constant screenings or tests being conducted by a COVID-19 task force, the recent ones being held in Dawaling and Yangphelthang. [6]

Both Nepal and Bhutan have managed to commence their vaccination drives promptly. It is here that the overarching presence of India for these two countries may be assessed through the former’s ‘Vaccine Maitri’ initiative.

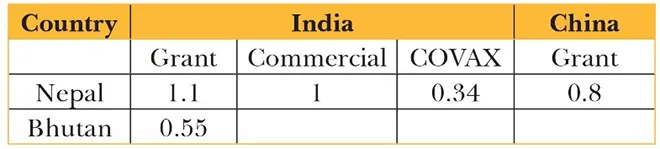

India emerged as a first responder to the COVID-19 crisis in its immediate neighbourhood, through its diplomatic outreach with vaccines. The first consignment was delivered to Bhutan in January 2021, with 0.55 million doses on a grant basis, from the Serum Institute of India in Pune.[7] Similarly, 1.1 million doses were granted to Nepal, in addition to which the country purchased 1 million doses from the institute and also received 0.34 million doses under COVAX[a] in March 2021.[8]

As India began suffering the impact of the massive second wave, many countries stepped up to give aid. Bhutan, for example, sent 40 metric tonnes of liquid oxygen from its new plant at Samdrup Jongkhar.[9] It was time for Bhutan to reciprocate India’s help, as the situation in the country became more manageable. Today Bhutan is on its way to vaccinate almost 90 percent of its eligible adult population of more than 530,000. The country procured around 5,900 Pfizer vaccine doses and other essential equipment for the drive from the Asian Development Bank and UNICEF. This is apart from the Indian vaccines.[10]

Nepal, for its part, could not extend any assistance to India as it was itself suffering massively, even as China has supplied 800,000 doses of Sinopharm vaccine as aid.[11] Nepal’s urgent need is to rollout the vaccine to the 1.3-million population of people above 65 years of age.[12]

China’s involvement in Nepal’s vaccine requirements, and India’s absence, has critical strategic connotations for the region. For the past year, India and Nepal’s relationship has been fraught, following the row over the political map of the Kalapani region.[13] India would have utilised its vaccine diplomacy to counter any tendency on Nepal’s part to tilt closer to China to meet its requirements. It was also an appropriate time for India, through genuine help and aid, to shed off its image of “superiority” in the region vis-a-vis the smaller neighbours, which has not always been accepted in good faith.[14] This was also a chance for India to counter the negative sentiments that had been generated among the Nepalese during the crisis brought about by the blockade of 2015. Indeed, Nepal is now leaning to China amidst cascading domestic challenges of the upcoming elections and a desperate need to roll out covid-related requirements to its population.[b]

Table 1: Supply of vaccines to Nepal and Bhutan from India and China (in million)

[caption id="attachment_87987" align="aligncenter" width="660"] Sources: Government and media reports[15][/caption]

Sources: Government and media reports[15][/caption]

India is hoping to be able to supply vaccines to Nepal and Bhutan in the coming days, as the Serum Institute has decided to establish manufacturing units abroad. It has also promised an output of 100 million doses by July 2021.[16] Till then, the future of India’s Himalayan neighbourhood remains uncertain.

[a] COVAX aims to ensure all countries have access to a safe, effective vaccine.

[b] There has been no comprehensive statement, opinion or response released by India on this shift.

[1]“Racing to Respond to the COVID-19 Crisis in S6outh Asia,” UNICEF South Asia.

[2]Regional Office for Southeast Region, World Health Organization COVID-19 Weekly Situation Report, Week No. 14, 05 April to 11 April 2021, (16 April 2021).

[3]Regional Office for Southeast Region, World Health Organization COVID-19 Weekly Situation Report, Week No. 20, 17 May- 23 May 2021, (28 May 2021).

[4]Regional Office for Southeast Region,World Health Organization COVID-19 Weekly Situation Report, No. 20

[5]“Bhutan,” World Health Organization Health Emergency Dashboard.

[6]Department of Information and Media, Royal Government of Bhutan, May 2021.

[7]COVID-19 Updates, “Vaccine Supply”, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India.

[8]COVID-19 Updates, “Vaccine Supply”, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India.

[9] “Bhutan to provide liquid oxygen to India to help combat COVID-19,” Press Trust of India, 28 April 2021.

[10]Rebecca Armitage and Lucia Stein, “Bhutan went from no jabs to being a world leader in COVID-19 vaccine rollout in three weeks. Here's how they did it,” ABC News, 19 April 2021.

[11]Penny MacRae, “In a repeat of India's devastating surge, Covid-19 is ravaging Nepal,” The Telegraph, 31 May 2021.

[12]Sonia Awale, “Aid pours into Nepal, but where be vaccines?” Nepali Times, 22 May 2021.

[13]Sohini Nayak, “India and Nepal’s Kalapani border dispute: An Explainer,” ORF Issue Brief, No. 356, Observer Research Foundation.

[14]“Vaccine Diplomacy: India’s winning for, now,” Deccan Herald, 26 January 2021.

[15] For India’s aid see, “Vaccine Supply”, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India.

For China’s aid see Penny MacRae, “In a repeat of India's devastating surge, Covid-19 is ravaging Nepal,” The Telegraph, 31 May 2021.

[16] “Serum Institute CEO plans to start Covid-19 vaccine production abroad,” Hindustan Times, 1 May 2021.

Myanmar and Thailand: China Steps Up its Vaccine Diplomacy

Sreeparna Banerjee

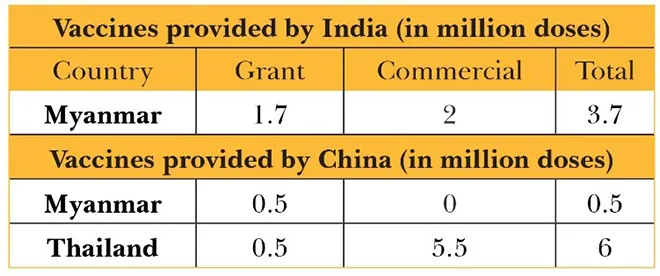

Myanmar, strategically significant for India as a bridge to Southeast Asia and a gateway to India’s North Eastern Region, received its first consignment of COVID-19 vaccines from India consisting of 1.7 million doses on 22 January 2021. Consequently, it signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the Serum Institute of India in Pune and ordered 30 million doses of Covishield vaccines,[1] a portion of which were dispatched on 11 February.[2] Following India’s initial rollout, the National League for Democracy (NLD)-led government of Myanmar started its nationwide COVID-19 vaccination drive on 27 January, with healthcare staff and volunteer medical workers being the first to receive shots of the donated AstraZeneca vaccines.

However, the February 2021 military coup disrupted the trajectory of the government’s pandemic response. Two days after the military takeover, on 3 February, healthcare workers and civil servants across the country launched a national Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) and refused to work under the military regime.[3] The following weeks saw the country’s doctors and nurses joining the CDM.[4]

In retaliation, the junta launched various violent attacks on healthcare workers. Three-month data covering the period 11 February to 11 May shows that there have been more than 170 incidents of assaults on health professionals. Ambulances have also been vandalised, and hospitals have been either raided, bombed, or occupied by military troops.[5] In the two months of April and May, arrest warrants were issued for around 400 doctors for their alleged participation in the CDM.[6]

Such incidents have impacted both the testing capacity and vaccination drive. The day before the coup, Myanmar had logged just over 140,000 cases and 3,131 deaths.[7] The number of total infections as of 2 June, stands at 143,751, with the death toll at 3,217.[8] According to the ruling junta, the number of people being tested daily for the virus has dropped to about 2,000 compared to nearly 25,000 before the coup.[9] While the junta has urged people to get vaccinated, the arrests and attacks on health professionals have naturally limited the number of those who can administer the vaccine. As of 23 April, more than 1.5 million people had received the first dose, but only 300,000 had received both doses.[10] Many people, including healthcare workers, are in hiding for fear of being arrested. As many were unable to take their second dose, 1.6 million vaccine doses ended up being wasted.

When India started suffering heavily from the second wave of COVID-19, many countries extended assistance in the form of medical supplies, equipment, therapeutic drugs, and other essentials. Myanmar, due to its own domestic political situation, has been unable to respond. At the same time, China has stepped in to give Myanmar assistance in vaccines. There is public resentment against China, however, as it has been key to the shielding of Myanmar against reprimand before the United Nations Security Council (UNSC); anti-coup sections of the Myanmar population are skeptical of the China-made vaccines donated in May.[11]

India’s other Southeast Asian neighbour, Thailand, is also under pressure. Dissatisfaction with the military-backed government's vaccine strategy has been building for months.[12] While the government managed to tackle the pandemic properly in 2020, this year the spike in numbers and the inability to secure adequate vaccine doses has hit the nation hard. At the time of writing this report, about 3.3 percent of the country’s roughly 69 million people have received at least one dose of vaccine.[13] The government has secured just 7 million vaccine doses in total but is in need of more. The public disapproves of the government’s decision to not join COVAX, which is subscribed to by the rest of ASEAN countries and almost every nation across the world. Thailand is putting its bet instead on a direct tie-up between AstraZeneca and Siam Bioscience, supplemented by China's Sinovac.[14] Moreover, media reports indicate that India had offered to sell to Thailand over 2 million doses of its AstraZeneca-licensed vaccine in January, but the Thai government refused the offer.[15]

To be sure, Thailand was among the countries that sent relief aid to India as the second wave hit the country.[16] The assistance is not unexpected, as India figures in Thailand’s ‘Look West’ policy and is regarded as a rising market.[17]

China, too, figures in Thailand’s vaccine strategy. China has donated 500,000 vaccine doses, a portion of which will be used to inoculate some 150,000 Chinese nationals based in Thailand.[18] The Thai government has also appealed to Russia and the United States for help; both have agreed and will be sending the vaccines soon.[19]

A group of Thailand-based American organisations is also leading an appeal to the US government to deliver vaccines to tens of thousands of Americans based in Thailand. The American government is yet to respond to the proposal.[20]

Table 1: Vaccines provided by India (in million doses)

[caption id="attachment_87988" align="aligncenter" width="660"] Sources: Government and media reports.[21][/caption]

Sources: Government and media reports.[21][/caption]

According to some analysts, China’s reliability as a vaccine supplier could increase its geopolitical clout in these nations.[22] China is the second-largest source of foreign investment and top trade partner for both Myanmar and Thailand.[23] Following the coup in Myanmar, China has acted as a guardian in the UNSC, blocking any attempt to subject the junta to international reprimand. Saying it wishes to respect Myanmar's sovereignty and the will of its people, China would like to play a constructive role in easing the tensions in Myanmar.[24] Whether its vaccine diplomacy can achieve this remains to be seen.

[1]“Myanmar orders 30 million coronavirus vaccines from India”, WION, January 2021.

[2] “Vaccine Supply”, Vaccine Maitri, COVID 19, Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi, May 29, 2021.

[3] “Citizens launch civil disobedience campaign on second day of Myanmar coup”, Business Standard, February 4, 2021.

[4] Karan Manral, “Myanmar protests: Doctors join 'civil disobedience' movement against coup”, Hindustan Times, March 22, 2021.

[5] “Violence Against Health Care in Myanmar”, Physicians for Human Rights, May 25, 2021; Helen Regan, “Myanmar military occupies hospitals and universities ahead of mass strike”, CNN, March 8, 2021.

[6] PHYSICIANS FOR HUMAN RIGHTS, May 25, 2021

[7]Zsombor Peter, “Aid Groups Fear COVID Third Wave in Post-Coup Myanmar”, VOA, April 9, 2021.

[8] “Myanmar Country”, Worldometer, June 2, 2021.

[9] VOA, April 9, 2021,

[10] “China Donates 500,000 COVID-19 Vaccines to Myanmar Junta”, The Irrawaddy, May 3, 2021.

[11] THE IRRAWADDY, May 3, 2021,

[12]Emmy Sasipornkarn, “COVID: Thailand's slow vaccine rollout sparks anger”, DW, May 20, 2021.

[13]ChalidaEkvittayavechnukul and Patrick Quinn, “Thailand Reports Record Virus Cases; Delays Bangkok Easing”, The Diplomat, June 1, 2021.

[14] DW, May 20, 2021,

[15]Cod Satrusayang, “Thai government confirms it received Indian vaccine offer last year in December”, Thai Enquirer, January 30, 2021.

[16]Srishti Jha, “Thailand Sends 100s Of Lifesaving Medical Aid To India Amid COVID Second Wave”, Republic World, May 8, 2021.

[17]Constantino Xavier, “Bridging the Bay of Bengal: Toward a Stronger BIMSTEC,” Carnegie India, February 22, 2018.

[18] “Coronavirus: 150,000 Chinese in Thailand start getting vaccinated; Singapore airport cluster likely linked to infected travelers”, The Coronavirus Pandemic, May 21, 2021.

[19] “FACT SHEET: Biden-Harris Administration Unveils Strategy for Global Vaccine Sharing, Announcing Allocation Plan for the First 25 Million Doses to be Shared Globally”, Press Release, The White House, June 3, 2021; Apinya Wipatayotin, “Sputnik V to launch here”, The Bangkok Post, April 23, 2021.

[20]Warangkana Chomchuen, “Overseas and Overlooked, Americans in Thailand Seek Vaccines”, VOA, May 10, 2021.

[21]Myanmar India data from MINISTRY OF EXTERNAL AFFAIRS, May 29,2021, Myanmar China data from THE IRRAWADDY, May 3, 2021,; Thailand data from Fu Ting and Patrick Quinn, “China, in global campaign, vaccinates its people in Thailand”, AP, May 20, 2021.

[22] “The world turns to China for Covid-19 vaccines after India, US stumble”, The Straits Times, May 7, 2021.

[23]RakhahariChatterji, “China’s Relationship with ASEAN: An Explainer”, Observer Research Foundation, April 15, 2021.

[24] “China says willing to engage with all parties to ease Myanmar situation”, Reuters, March 7, 2021.

Sri Lanka and Maldives: Island Nations Look to China and Russia for Vaccines

Vinitha Revi

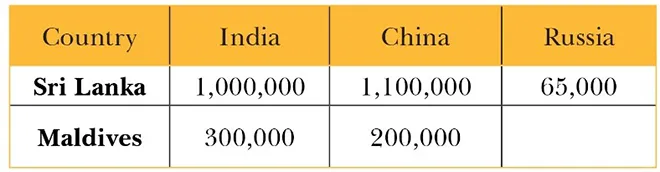

Sri Lanka and Maldives began their vaccination drives early this year utilising donations from India. This led to a great deal of pro-India rhetoric, with presidents of both countries taking to Twitter to thank India for its generosity.[1] Sri Lankan Minister of Plantations and government spokesperson, Ramesh Pathirana, in February 2021 even suggested that his country was likely to have only India’s Covishield AstraZeneca[a] for the second phase of the vaccination campaign as the Chinese and Russian vaccines were not ready yet.[2] However, things have changed since the beginning of May 2021 as the health situation in India took a turn for the worse. With a massive rise in cases and deaths across India, there has been a clear shift in the government’s vaccine diplomacy—i.e., a decided focus on dealing first with domestic demand. This has had an unintended yet critical impact on countries that had relied on India’s vaccines, including its island neighbours, Sri Lanka and Maldives. Both countries, following India’s donations in January, placed direct orders with the Serum Institute of India (SII) for the AstraZeneca-Covishield vaccine.

On 25 May 2021, the Colombo Gazette reported[3] that the Sri Lankan government does not believe that SII will be capable of delivering the remaining orders for the Covishield vaccine; Minister Pathirana said that SII was yet to deliver an earlier order of 600,000 doses. He pointed out that when Sri Lanka placed its order for the vaccine, India was not yet battling a serious second wave. Pathirana said the government would be needing to look at alternatives to address the shortage; they are considering different options including mixing vaccine brands—if such strategy is approved by the World Health Organization (WHO).[4] Negotiations are also underway to purchase from manufacturers of AstraZeneca vaccine in other countries, as well as directly from countries where there is an excess of AstraZeneca doses. The existing supply of AstraZeneca in Sri Lanka is being used as a second dose for those who have already received their first shot; frontline workers are being given priority.[5]

President Gotabaya Rajapaksa has said that he will ensure that the maximum number among its 21.8-million population will get vaccinated as soon as possible.[6] He has instructed officials to expedite both import procedures and the vaccine rollout.

To fill the shortage caused by the non-delivery of AstraZeneca-Covishield, Sri Lanka is looking to source vaccines from China and Russia. The country has ordered 185,000 doses of Sputnik V from Russia,[7] with the first consignment of 15,000 doses coming on 4 May 2021[8] and 50,000 more doses to have been delivered on 27 May 2021.[9] Meanwhile, from China, Sri Lanka has so far received two batches of Sinopharm vaccines as donations. At a handover event, China’s ambassador to Sri Lanka, Qi Zhenhong, mentioned his government’s plans to deliver another 2 million vaccine doses.[10] The State and Acting Deputy Health Minister Channa Jayasumana said that following discussions held between the two countries, the Sri Lankan government intends to commence the local production of China’s Sinovac vaccine.[11]

Table 1: Vaccines Supplied to Sri Lanka and Maldives (excluding doses supplied through COVAX)

[caption id="attachment_87989" align="aligncenter" width="660"] Sources: Government and media reports[12][/caption]

Sources: Government and media reports[12][/caption]

Maldives has been experiencing an alarming surge in cases since the beginning of May 2021 despite having vaccinated nearly 60 percent of its population of 57,426. According to updates from the Health Protection Agency, 165,181 people have had two doses of vaccines, and 309,444 have had one dose.[13] Maldives was initially using China’s Sinopharm and India’s Covishield, and later approved the emergency use of Pfizer on 15 March 2021, and of Sputnik V on 12 May 2021.[14] During a phone call on 27 May, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov gave assurances to his Maldivian counterpart, Abdulla Shahid, that his government was committed to expedite the supply of vaccines to Maldives.[15]

Maldives officially commenced its vaccine rollout on 1 February 2021, after receiving a donation of 100,000 doses of Covishield from India on 20 January 2021. An additional donation of 100,000 doses were delivered on 20 February 2021. A third consignment of 100,000 doses were supplied under the Vaccine Purchase Agreement signed on 29 March 2021 between the Maldives’s Ministry of Health and SII.[16]

Maldivian news outlets in late May reported President Ibrahim Mohamed Solih’s announcement that his government had decided to order vaccines from Russia as they were unsure of when the AstraZeneca vaccine from India would be delivered.[17] President Solih also said that Maldives was in discussions with a number of other nations for vaccine supply. The government has signed an agreement with AstraZeneca’s Singaporean company to secure an additional 700,000 doses, but the shipment has been delayed.[18]

Both Sri Lanka and Maldives have been extremely sympathetic to India’s spiralling health crisis, and their government officials have often explained the situation to their own publics. To be sure, however, the situation in India has created challenges for their vaccine rollouts. These are historically unparalleled times in which both India and its island neighbours find themselves dealing with urgent challenges. In times of crises, all countries, whether big or small, are likely to look inward. It remains to be seen how these specific decisions made by individual countries will impact the changing dynamics of international relations in the future. As India’s neighbours turn to China, Russia, and other countries to address the shortage in vaccines caused by the health crisis in India, it will be particularly important to watch how these decisions will impact on China’s already growing influence in South Asia.

[a] Covishield is the Made-in-India Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine being manufactured by the Serum Institute of India (SII), Pune.

[1]President Ibrahim Solih, @ibusolih “A short while ago, a flight from India with a 100,000 doses of the CoviShield vaccine arrived in the Maldives, renewing our hopes for a resolution to the Covid 19 crisis soon. Our heartfelt thanks to PM @narendramodi government and people of India for this most generous gift,” Twitter, 20 Jan 2021.

President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, @GotabayaR, “Received 500,000 #COVID—19 vaccines provided by #peopleofindia at #BIA today". Thank you! PM Shri @narendramodi & #peopleofindia for the generosity shown towards #PeopleofSriLanka at this time in need.

[2]“Sri Lanka orders 13.5 million AstraZeneca doses, likely to drop Chinese COVID19 vaccines,” The Hindu, February 23, 2021.

[3]“Sri Lanka looking at alternatives as no hope on Serum,” Colombo Gazette, May 25, 2021.

[4]“Mix and Match to be considered if WHO approves,” Colombo Gazette, May 4, 2021.

[5]“Sri Lanka looking at alternatives as no hope on Serum,” Colombo Gazette, May 25, 2021.

[6]President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, @GotabayaR, Twitter, May 26 2021.

[7]Easwaran Rutnam, ‘Sri Lanka to receive another 185,000 doses of Sputnik V’ Colombo Gazette, May 18, 2021.

[8]“Sri Lanka to begin using the Sputnik V vaccine from tomorrow,” Colombo Gazette, May 5, 2021.

[9]“50,000 doses of the Sputnik V vaccine arrive in Sri Lanka,” Colombo Gazette, May 27, 2021.

[10]“Second stock of Sinopharm vaccines to be added to vaccination drive from today” Press Release, Government of Sri Lanka, May 26, 2021.

[11] “Second stock of Sinopharm vaccines to be added to vaccination drive from today,” Government of Sri Lanka, May 26, 2021.

[12] For India’s aid to Sri Lanka and Maldives see, Government of India, “Vaccine Supply,” Ministry of External Affairs, May 29, 2021.

For China’s aid to Sri Lanka see, “Sri Lanka receives 600,000 doses of China's Sinopharm vaccine: Official,” The Hindu, March 31, 2021, and “Sri Lanka gets 2nd vaccine donation from China,” The Times of India, May 26, 2021.

For China’s aid to Maldives see, Government of Maldives, “China donates 200,000 doses of Sinopharm vaccine to the Maldives,” Ministry of External Affairs, March 25, 2021.

For Russia’s aid to Sri Lanka see, “Sri Lanka to begin using the Sputnik V vaccine from tomorrow,” Colombo Gazette, May 5, 2021, and “50,000 doses of the Sputnik V vaccine arrive in Sri Lanka,” Colombo Gazette, May 27, 2021.

[13]Health Protection Agency, @HPA_MV, Twitter Update, May 29, 2021.

[14]Ministry of Health, Government of Maldives, “Approval of Sputnik V” & “Approval to Use Pfizer”.

[15]Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Government of Maldives.

[16]High Commission of India, Male, Government of India.

[17] Ahmedulla Abdul Hadi, “Maldives to source 200,000 Sputnik V vaccine doses from Russia” SunOnline, May 25, 2021.

[18]Aishath Hanaan Hussain Rasheed, Pres. Solih maintains Covid-19 management has not failed, promises subsidies to citizens alongside stronger restrictions, Raajjee, May 26, 2021.

Pakistan and Afghanistan: Defining Equations in the Time of COVID-19

Saaransh Mishra

As India commenced its “vaccine diplomacy”[1] in January 2021, the country supplied substantial doses of vaccines to countries in its neighbourhood.[2] Not surprisingly, India’s immediate western neighbour, Pakistan, with 0.9 million cases and 21,000 deaths so far was missing from the list of recipients. In March, the Indian Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) by way of explanation, said that they have not received any requests for vaccines from Pakistan.[3]

India and Pakistan’s historically fraught relations have come under greater pressures in recent times, owing to terrorist attacks,[a] surgical strikes,[b] and the Indian government’s revocation of Jammu & Kashmir’s special status.[c] Consequently, bilateral trade has been adversely affected, although the supply of “life-saving” medicines were exempt.[4] Pakistan has also been able to secure 45 million India-made vaccines through the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI) for which it signed an agreement in September 2020.[5] Notably, India invited Pakistani diplomats in February 2021 to get inoculated, as part of the government’s outreach to the foreign diplomatic community in Delhi.[6] Apart from this, there has been no direct offer by India, and neither has Pakistan asked for any assistance. Pakistan has mostly relied on its trusted ally, China, for vaccines.

India halted the exports of vaccines in March as it got hit hard by the second wave of the pandemic. This decision has had an impact on various countries.[7] Pakistan, although not directly dependent on India, also suffered a setback as it was highly dependent on COVAX. The goal of COVAX is to supply Pakistan with enough doses to vaccinate 20 percent of its population;[8] three-fourths of its entire supply of vaccines were expected to be manufactured in India. Pakistan is thus having to re-engineer its entire vaccine strategy.[9] Such rethinking has involved China, from where Pakistan has purchased 1 million doses of Sinopharm, and 60,000 doses of CanSino vaccines in mid-March.[10]

To be sure, Pakistan offered to send relief materials to India during the initial onslaught of the second wave.[11] In the same statement, however, Foreign Spokesperson Zahid Hafeez Chaudhary called on India to release all the Kashmiri prisoners as a humanitarian gesture amidst the pandemic.[12] This conditional offer only reveals Pakistan’s intent to utilise India’s COVID-19 crisis to push its own agenda.

India’s vaccine diplomacy could have helped mend longstanding strained relations and counter Chinese influence in Pakistan. However, India’s unwillingness to engage with Pakistan, as the latter’s offer bears undercurrents of the contentious Kashmir issue, is testimony to fraying bilateral ties.

Apart from China, Russia had also sent Pakistan 50,000 doses of Sputnik V vaccines by 7 April and is due to send 150,000 more doses soon.[13] While Russia-Pakistan ties are more nascent, Russia could possibly be coming to Pakistan’s aid given the latter’s strong influence in Afghanistan. Russia has stakes in Afghanistan, primarily, concerns about drug-trafficking, as well as the presence of the Islamic State and the resultant threats to its Central Asian allies.[14] Russia and Pakistan are the closest they have ever been, with the possibility of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s first visit to Islamabad later this year or in early 2022.

India has been one of Afghanistan’s most trusted development partners since the end of Taliban rule in 2001.[15] India has interests in Afghanistan pertaining to the Central Asian energy markets and broader connectivity projects.[16] Therefore, Afghanistan was predictably one of the foremost beneficiaries of India’s vaccine diplomacy in the near-neighbourhood. At the time of writing this report, Afghanistan had 74,000 COVID-19 cases and 3,000 deaths; the real numbers, however, could be higher, owing to massive underreporting in the war-torn country. India has supplied 968,000 vaccine doses to Afghanistan in two phases so far—500,000 in February and 468,000 in March via Covax.[17] India has also supplied Afghanistan with hydroxychloroquine and paracetamol tablets and 5,000 tonnes of wheat as aid,[18] for which the government has expressed gratitude.[19] For its part, the country has expressed solidarity with India in its battle against the second wave of COVID-19.[20]

The sudden halt of vaccine exports from India has compelled Afghanistan to look to China and Russia as alternative donors. In March, China pledged 400,000 doses of Sinopharm,[21] and there had also been discussions about a possible handover of a batch of Sputnik-V vaccines;[22] neither of these have arrived in Afghanistan. Will China and Russia in fact deliver on their promise, and fill the vaccine gap in Afghanistan? If they do, will it sideline India?[23]

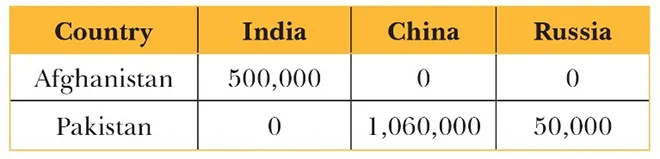

Table 1: Vaccines Supplied so far to Afghanistan and Pakistan (excluding doses supplied through COVAX)

[caption id="attachment_87990" align="aligncenter" width="660"] Source: Government and Media reports.[24][/caption]

Source: Government and Media reports.[24][/caption]

Vaccine diplomacy in Afghanistan is crucial for India: it could strengthen its involvement—so far, peripheral—in the peace process.[25] In March, the US Secretary of State officially included India in the ‘process’ through a plan for the future of Afghanistan that outlined the crucial role of regional actors including India.[26] The inclusion could possibly lead to an enhanced role for India in Afghanistan, post-US withdrawal; this, paired with India’s prompt vaccine supply as well as the Afghan Foreign Minister’s recent three-day visit to Delhi in March 2021, where he emphasised on not only collaboration to overcome COVID-19, but precisely the need for a greater Indian role in the peace process.[27]

The challenge is that Pakistan still stands as a huge roadblock given its closeness with the Taliban,[28] which continues to wield influence in Afghanistan.[29] Pakistan, backed by China and Russia both of which have interests in Afghanistan, could cause India to be further sidelined in Afghanistan. Therefore, as vaccine diplomacy determines the fate of strategic equations in India’s western neighbourhood, the halt of India’s vaccine outreach and the resultant scope for opportune involvement of other global powers, could bring serious implications for the region.

[a] The attacks being referred to here are the Uri Attack on 18 September 2016 and the Pulwama attack on 14 February 2019. Both the attacks were perpetrated by the Jaish-e-Mohammad that is based in Pakistan.

[b] In response to the Uri terror attacks in 2016, India conducted “surgical strikes” against militant launch pads across the Line of Control in Pakistani-administered Kashmir. India also conducted the Balakot airstrikes in 2019, in response to the Pulwama attack.

[c] On August 5, 2019, the Government of India amended Article 370 of the Indian Constitution which led to the bifurcation of the erstwhile state of Jammu & Kashmir into two Union Territories, namely UT of Jammu and UT of Ladakh.

[1] Sai Balasubhramanian, “Vaccine Diplomacy: A New Frontier in International Relations”, Forbes, February 24, 2021.

[2] “Pakistan to receive 45 million ‘Made in India’ Covid-19 vaccines under Gavi alliance”, Business Today, March 10, 2021.

[3] “No request received for coronavirus vaccines: MEA spokesperson”, The Economic Times, January 22, 2021.

[4] Shubhajit Roy, “India to supply COVID-19 vaccines to Pakistan”, The Indian Express, March 10, 2021.

[5] “Pakistan to receive 45 million ‘Made in India’ Covid-19 Vaccines under Gavi alliance”.

[6] “India invites Pakistani Diplomats for COVID-19 Vaccination, Pak to take call”, India.com, February 02, 2021.

[7] Jeffrey Gettleman, Emily Schmall and Mujib Mashal, “India cuts back on vaccine export as Infections Surge at Home”, The New York Times, March 25, 2021.

[8] “Pakistan receives first consignment of COVID-19 vaccines via Covax facility”, World Health Organization (Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean), May 8, 2021.

[9]“Pakistan receives first consignment of COVID-19 vaccines via Covax facility”.

[10] “Pakistan buys 1 million COVID vaccines doses from China”, The Economic Times, March 24, 2021.

[11] “Pakistan reiterates its offer to provide relief materials to India to help fight Covid-19”, The Times of India, April 29, 2021.

[12] “Pakistan reiterates its offer to provide relief materials to India to help fight Covid-19”.

[13]Sidhant Sibal, “Russia offers vaccine to Pakistan from production lines I India, other countries”, Dna India, April 7, 2021.

[14]Abubakar Siddique, “Explainer: What does Russia want in Afghanistan”, RadioFree Europe Radio Liberty, June 29, 2020.

[15] Sohini Bose, “Bridging the Healthcare gap in Afghanistan: A primer on India’s role”, Observer Research Foundation, April 16, 2020.

[16] Harsh V. Pant and Shubhangi Pandey, “How India came around to talking to the Taliban”, Observer Research Foundation, September 26, 2020.

[17] “Vaccine Supply”, Ministry of External Affairs.

[18] “Afghan Prez Ghani thanks India for supplying HCQ, wheat amid Covid-19 pandemic”, Hindustan Times, April 20, 2021.

[19] “Afghanistan receives first batch of Covid-19 vaccine from India”, The Print, February 07, 2021.

[20] “Afghanistan President extends support to India amid Covid-19 surge”, ANI, April 25, 2021.

[21] “China ‘to provide 400,000 COVID vaccine doses’ to Afghanistan”, Al Jazeera, March 1, 2021.

[22] “Afghanistan ready to consider purchase of Russia’s Sputnik V vaccine- ambassador”, Tass, May 29, 2021.

[23]Harsh V. Pant and Kriti M. Shah, “India joins the Afghan Peace Negotiations”, Foreign Policy, March 25, 2021.

[24]For aid from India see, “Vaccine Supply”, Ministry of External Affairs (Government of India).

For China’s aid to Pakistan see, “Pakistan buys 1 million covid vaccine doses from China,” Healthwordl.com, March 24, 2021.

For Russia’s aid to Pakistan see, Sidhant Sibal, “Russia offers vaccines to Pakistan from production lines in India, other countries,” April 7, 2021.

[25] Pant and Shah, “India joins the Afghan Peace Negotiations”.

[26] Pant and Shah, “India joins the Afghan Peace Negotiations”.

[27]Rezaul H. Laskar, “Looking at greater role for India in peace process, says Afghan foreign minister”, Hindustan Times, March 24, 2021.

[28]Ajish P. Joy, “Why India should talk to the Taliban”, The Week, March 15, 2020.

[29]Saaransh Mishra, “Can China, Pakistan and India cooperate in Afghanistan”, Observer Research Foundation, May 24, 2021.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Sohini Bose is an Associate Fellow at Observer Research Foundation (ORF), Kolkata with the Strategic Studies Programme. Her area of research is India’s eastern maritime ...

Read More +