Introduction

A free trade agreement allows for duty-free trade within a specified area, and members set their own tariffs on imports from non-members.[1] The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) adopts a broader notion that includes non-tariff barriers as well, defining a free trade area as “a grouping of countries within which tariffs and non-tariff trade barriers between the members are generally abolished but with no common trade policy toward non-members.”[2] Countries in geographical proximity often enter into preferential trade agreements that allow member countries outside the boundaries of sovereign nations both market access and non-discriminatory treatment, among other facilities.

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), for example, is a free trade area between the United States (US), Mexico, and Canada; the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Free Trade Area is an arrangement between the ten ASEAN member states;[3] the South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA) is the free trade arrangement of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC); and the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is an agreement between 54 out of 55 African Union members.[4]

This paper focuses on the AfCFTA. It outlines the benefits of the AfCFTA and weighs such potential against the challenges. It then discusses how India can harness the potential of the agreement.

Africa’s Trade Integration: Gradual, Fragmented

The African continent first engaged in trade integration after independence, with the establishment of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in 1963 comprising 32 countries. The cornerstone of this attempt at integration was promoting understanding and cooperation among the member states. In the initial years, the purpose of the integration was largely political. Over a few decades, commercial and economic interests gained prominence, with the aim of nurturing self-reliance for the African continent. To further the commercial integration in the continent, in 2002, the African Union[5] replaced the OAU.

Today the African Union is the largest regional grouping in the world with 55 member states.[6] Among its goals is to promote free trade within Africa, and in 2012, it decided to establish a free trade area. This resulted in the adoption and signing of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) in 2018. Regarded as a flagship project of the larger agenda called the Africa’s Development Framework Agenda 2063,[7] the AfCTA is a preferential arrangement that includes a Free Trade Agreement and a Protocol for Free Movement of Persons. It entered into force in May 2019 and trade under AfCFTA began on 1 January 2021. As of 7 July 2021, 37 countries have ratified the AfCFTA.[8] The scope of AfCFTA covers tariff reduction, removal of non-tariff barriers, and the promotion of the free movement of people and services. It is one of the world’s largest free trade areas with a market economy of nearly 1.2 billion people.[9]

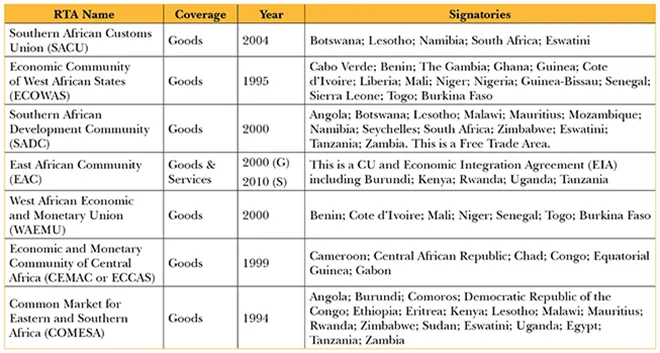

This is the first trade agreement covering nearly the entire continent. Prior to this, however, there have been several regional/zonal groupings within Africa and agreements between certain countries, organised in the form of Customs Union, with common external tariff. For instance, the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), which is a customs union, came into force in 1994 and has a current membership of 21 African nations. This was followed by the formation of the Economic Community of Western African States (ECOWAS), also a customs union, which came into force in 1995. There are similar unions between countries in Southern Africa, Eastern Africa, and Central Africa (See Table 1). Therefore, the different zones in Africa are already integrated through preferential agreements. The AFCFTA builds on these regional cooperation agreements, with the aim of creating a single market for the African continent and thereby, reaching a higher level of integration for movement of both people and capital.

Table 1: Free Trade Arrangements within Africa

Source: Compiled by author from the World Trade Organization’s database of Regional Trade Agreements.[x] This list excludes Community of Sahel-Saharan states, as the group is not notified in the WTO.

The process of Africa’s own integration has been slow and rather delayed. At the same time, however, a number of large African nations have existing preferential arrangements with countries outside the continent, particularly the erstwhile colonisers. A few African countries, for example, have preferential arrangements with the member states of the European Union (EU). The trend is more prominent in the case of larger African economies,[a] such as Nigeria, Egypt, South Africa, Algeria, and Morocco. There are also countries that have integration arrangements with the United States (US), and India.

AfCFTA’s Trade and Investment Potential

There is no dearth of evidence of the benefits that a free trade area can bring to its participating economies.[11] In the case of Africa, one of the objectives of the free trade area is to enhance intra-Africa trade and boost its position in the global market.[12] The share of intra-Africa exports as a percentage of Africa’s total exports is only 17 percent, which is much lower than other regions. In comparison, internal trade within North America is at 31 percent; Asia, 59 percent; and Europe, 69 percent.[13]

Owing to colonial history, the nature of the countries’ resource endowments and the state of their infrastructure, the African market is currently more outward-oriented. This paper argues that with the creation of a free trade area, African enterprises will gain access to an expanded consumer base and diverse resources within Africa. According to estimates by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Africa’s export potential is around USD21.9 billion.[14] AfCFTA could boost intra-African trade by about 33 percent and cut the continent’s trade deficit by 51 percent. This can be achieved through trade diversification, creation of value chains, and increased opportunities for foreign trade and investments.

Further hindering the growth of intra-African trade is a historical single-commodity focus that has resulted in internally disconnected economies.[15] To be sure, most African countries have a strong natural resource base. However, the nature of these resources and their endowments vary—this creates opportunities for export diversification as well as creation of value chains. Some countries such as Nigeria, Algeria and Egypt, for instance, are well-endowed with petroleum, natural gas, and iron ore; meanwhile, Morocco is rich in phosphate; Ethiopia, for its part, has hydropower, natural gas, gold and copper; Lesotho has precious stones; and Cote d’Ivoire has palm oil and coffee. Diversification can help the countries derive the benefits of regionalism.

The reduction of inter-Africa tariffs, or their elimination altogether, can lead the way to a unified market. This in turn is likely to aid product diversification and transition from a single commodity/raw material exporter to a transition to value-added products.[16] This will facilitate Africa’s integration in global value chains and help the countries diversify their exports to include manufactured goods, processed food, chemical- and energy-intensive manufactured products, among others.[17]

This is not to say that the African continent is monolithic. Indeed, there are regional inequalities when it comes to intra-Africa trade: it is the highest in SADC (84.9-percent share in Africa’s total trade), and the lowest in ECCAS (17.7 percent).[18] There are various factors that drive these differences in the levels of intra-regional exports, among them: degrees of complementarities in production structure; different levels of industrialisation and economic development; political-economy issues; and level of export diversification.[19] This also affects the establishment of regional value chains and Africa’s integration in global value chains (GVCs).

At present, trade within regional value chains is low in Africa and most of the trade is with countries outside the region.[20] With these trade partners outside the continent, African countries largely export primary goods. Further, there is growing disparity across Africa as its participation in GVCs is largely driven by North and Southern African countries, occupying a 78-percent share in the continent’s total value chain trade.[21] The integration is largely with European and Asian countries. With a reduction in internal tariffs, AfCFTA can facilitate internal sourcing within Africa and the establishment of manufacturing. This will help in the creation of production linkages and in upscaling the manufacturing capacity, for integrating African enterprises with the GVCs. Moreover, at present, much of Africa’s participation in GVCs is by means of forward integration—i.e., it provides the inputs for another country’s exports.[22] The value-added component remains limited.

The elimination of internal tariff will facilitate movement of raw materials and natural resources across Africa.[23] It is worth mentioning that trade agreements follow either a ‘positive list’ or a ‘negative list’ approach for scheduling commitments. Existing studies highlight that the AfCFTA provides for an ‘exclusion list’ – drawn along the lines of a negative-list approach.[b] Further, the schedule will be subject to an anti-concentration clause wherein the members cannot include an entire product or service section in the negative list.[24] This will ensure that a sector is not completely kept out of trade negotiations. In that sense, therefore, AfCFTA favours the liberalisation of trade.

Apart from trade diversification and developing value chains, there are other potential benefits from AfCTA. The agreement could enable the establishment and growth of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) within Africa, especially by aiding the availability of inputs and raw materials at low cost.

This will be highly relevant, as SMEs account for almost 80 percent of employment in Africa, providing many jobs amidst high unemployment rates. Data from the World Bank shows that the average unemployment rate in Africa is more than 10 percent.[25] To be sure, there is wide variation: in some countries such as South Africa, for example, the recorded unemployment rate was 28 percent in 2017;[26] in Djibouti it was 40 percent in the same year; in Sudan, nearly 20 percent; and in Nigeria, it was 16.5 percent. Other countries had lower unemployment rates: Egypt had 7.8 percent, Mauritius, 6.6 percent, according to 2019 data; meanwhile, from 2017 data, Seychelles had 3 percent; Guinea, 2.7 percent; Madagascar, 1.8 percent; and Niger, 0.3 percent.

Limited access to finance and resources, as well as lack of interest in entrepreneurship and poor education, are some of the factors responsible for high unemployment rates in some parts of the continent.[27] One of the cornerstones of the AfCFTA is to promote mobility of people within Africa, especially where there are greater labour market flexibilities and job opportunities.

All this is not to say that the AfCTA will benefit all member economies equally. Various studies have found that there is vast income disparity within Africa; a free-trade agreement can, therefore, potentially exert unequal pressure on relatively weaker market economies.[28] According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO),[29] the average Gini index[c] for sub-Saharan Africa is one of the world’s highest. A majority of the wealth is concentrated in the mining and oil-producing countries such as South Africa, Egypt, Nigeria, Morocco, and Kenya.[30] In such a scenario, analysts argue, while agreements such as AfCFTA may be economically viable and beneficial for some countries such as Egypt and Morocco,[31] greater benefits can be harnessed by exploring opportunities in the smaller economies. Interestingly, some of the least-developed countries in Africa enjoy certain benefits under the provision on Special and Differential Treatment (SDT) of the WTO. Given the advantages, these countries may attract greater investments that can contribute to their development.

Studies highlight the potential of the free trade area to attract more foreign investments into Africa, in turn boosting domestic industries.[32] While the current investments are largely directed towards extractive industries, growth prospects in the domestic market may attract investments in other sectors including agriculture, food processing, and services. It could promote the growth of manufacturing and create employment opportunities within Africa.[33] It is also argued that this may result in improved wages and larger benefits for women and unskilled workers.[34] A number of Indian companies have invested in the African market and it is believed that with the trade unification of Africa through the AfCFTA, India’s investments in the continent may increase further.

There is, however, need for caution as this also creates a risk of free-riding on the benefits of AfCFTA by third-parties, especially because the rules of origin in AfCFTA are different from those in certain regional agreements. Due to the prior trade agreements and presence of benefits due to SDT, some African countries may be preferred over others for establishing trade relations. For instance, COMESA applies a 35 percent value addition, while SADC has product specific rules of origin.[35] There may also be issues with the implementation of technical measures to check the imposition of non-tariff barriers to trade due to the size of the continent and economic disparity between the African countries.

Africa and India: Shared Histories, Diversified Trade and Investment

India has historical ties with Africa that pre-date the Independence period.[36] After Independence, India began to establish commercial relations with countries in Africa. One of India’s first preferential agreements with African countries was signed in 1974 with Senegal. It was a limited agreement covering goods, requiring parties to accord most-favoured-nations (MFN) treatment to each other. No binding tariff commitments were made at the time.

This was followed in the 1980s by a series of trade agreements, which became a key component of India’s then emerging international trade policy focused on facilitating greater economic cooperation among developing countries. Trade agreements were signed with Ghana (1981), Uganda (1981), Zimbabwe (1981), Angola (1986), and Zaire (now Congo, 1988). Most of these agreements were constitutional in nature, without any specific tariff commitments. They only required the contracting parties to accord MFN treatment to each other in the absence of any specific tariff commitments. In some cases, such as under the agreement with Senegal, a specific list of goods for promotion of trade was specified. However, none of these agreements were subsequently notified under the WTO.

More recently, India has concluded a preferential agreement with Mauritius, which covers goods, services and investments, among others. India is also negotiating the India-SACU Preferential Trade Agreement and the India-COMESA Preferential Trade Agreement. In addition to this, as a signatory to the Global System of Trade Preferences (GSTP) among developing countries, India accords tariff preference to the member countries, including those from Africa. India also launched the duty-free scheme for least developed countries (LDCs) in August 2008, which was later revised in 2014. Accordingly, import duties were removed for nearly 98 percent of the tariff lines. African LDCs can also avail these benefits.[37]

Bilateral Trade

In terms of bilateral trade, the African Union is one of India’s largest trading partners after the United States (US), China, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). With a share of 8.52 percent in world trade, India’s total trade with Africa in 2019 was valued at USD 68.33 billion. India has a negative trade balance with Africa, implying a dominance of imports over exports. In 2019, India’s trade deficit with Africa was valued at USD 9.1 billion, which accounted for nearly 6 percent of India’s total trade deficit in the case of trade in goods.

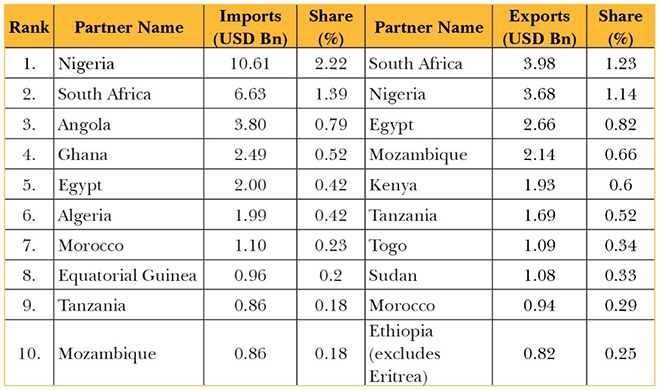

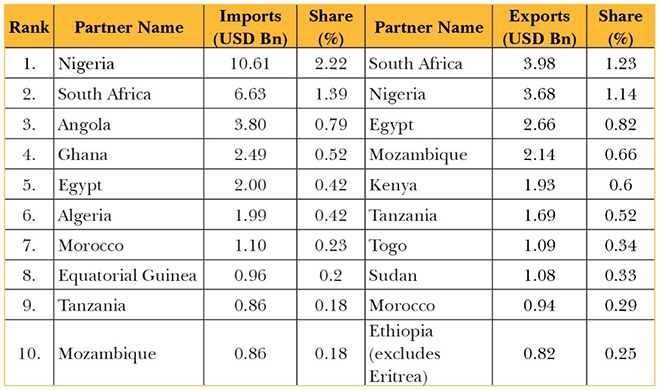

Within the African Union, India’s top trading partner is Nigeria (20.91 percent).[38] (See Table 2) Ten countries account for nearly 60 percent of India’s total trade with Africa. Of them, India enjoys a positive trade balance with Egypt and Mozambique; India has a deficit with all the others.

Table 2: India’s Top 10 Trade Partners in Africa and their Share in World Trade (2019)

Source: Compiled by author from the World Integrated Trade Solutions (WITS) database of the World Bank.[39]

In 2019, India’s total exports to the African Union amounted to USD 29.59 billion and imports were valued at USD 38.74 billion. A majority of India’s imports from the African Union originate from Nigeria (27.39 percent), followed by South Africa (17.12 percent), Angola (9.81 percent), Ghana (6.44 percent), and Egypt (5.17 percent). Meanwhile, India’s exports are directed towards South Africa (13.46 percent), Nigeria (12.43 percent), Egypt (8.98 percent), Mozambique (7.22 percent), and Kenya (6.53 percent).

In terms of the key items of trade – in 2019, nearly 61 percent of India’s imports from the African Union comprise of fuels, largely crude oil from Nigeria, Angola and Algeria; this is followed by precious stones and glass (~20 percent) from Ghana, South Africa and Botswana. There are other items of imports such as vegetables, metals and minerals that originate from various African countries including Benin, Sudan, Zambia, South Africa, Morocco and Cote d’Ivoire.

There is more diversity in India’s exports to Africa. In 2019, about 20 percent of the total exports comprised of fuels – including non-crude petroleum oil to Mozambique, Togo, Tanzania, Kenya and South Africa, among others; chemicals (18.50 percent) including pharmaceutical products to Nigeria, Egypt and Kenya; machines and electricals (12.59 percent) to Nigeria, South Africa and Egypt.

Thus, while much of the trade is with Nigeria and South Africa, India has trade linkages with other smaller African countries. Over the recent decades, India’s trade with Africa has become more diverse.[40] There has been a shift in India’s export basket to the continent, from textile yarns to petroleum products, pharmaceutical products, chemicals and manufactured products. At the same time, India’s import basket, though dominated by primary products and natural resources, is still diverse given the wide natural resource base in Africa.

Direct Investments

In the five years between 2015 and 2020, India received foreign direct investments (FDI) worth approximately USD 62.8 billion[41] from Africa; during the same period, Indian investments in Africa amount to around USD 20.1 billion.[42] India’s bilateral investments with Africa are atypical, as in most cases the investments can be linked to India’s existing bilateral agreements with African countries.

A majority of the inflow of investments from Africa to India originate from one country—i.e., Mauritius. It is the single-largest investor in India with a share of 28 percent in India’s total cumulative FDI inflows during April 2000-March 2021.[43] Within Africa, as of May 2021, almost 99 percent of the total FDI originated from Mauritius. This can be explained by the fact that the country is a tax haven, and a majority of the investments are round-tripped to India. The Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement (DTAA) between India and Mauritius allows Indian companies to avail the lower tax rates in Mauritius.[44]

Excluding Mauritius, over the last five years (2015-2020), India received investments from South Africa, Seychelles, Mozambique, and Uganda. Telecommunications services, cement manufacturing, financial leasing, power generation, air transportation activities, and advertising services, among others, are some of the key sectors in which India has received FDI from Africa. If investments from Mauritius are excluded, some of the key areas of investment include healthcare services (largely from South Africa), manufacturing of pharmaceutical products (Seychelles, Mozambique and South Africa) and financial services (South Africa).

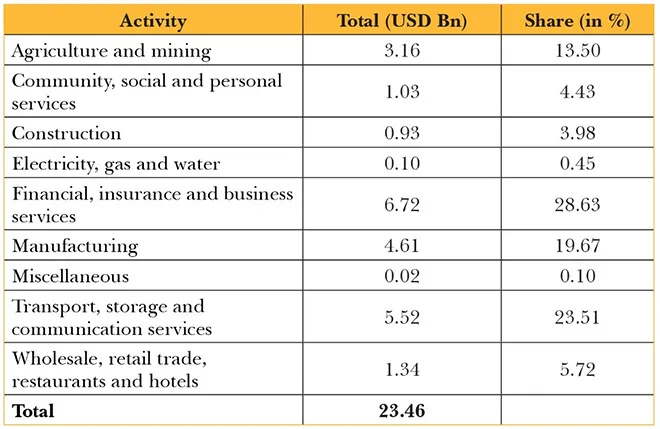

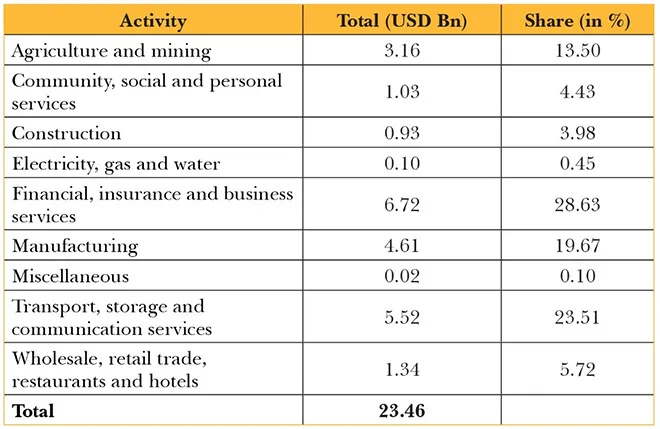

In terms of India’s outward investments to Africa, between January 2015 to May 2021, a total of USD 23.3 billion has been invested from India to Africa. A majority of these investments are made in Mauritius (84 percent) followed by Mozambique (11 percent) and South Africa (1 percent). In Mauritius, a majority of these investments are made in financial services, followed by transport, storage and communication services. In Mozambique, a majority of the investment is directed towards mining and in South Africa, they are directed to financial services. (See Table 3)

Table 3: India’s Investments in Africa (Jan 2015-May 2021, By Sector)

Source: Compiled by author from Reserve Bank of India (RBI) database.

Overall, financial services, telecommunications services, and mining are among the largest recipients of FDI from India to Africa. Some of the large investors from India with overseas investments in Africa are ONGC Videsh Limited, Bharti Airtel Limited, Vedanta Limited, Shapoorji Pallonji Infrastructure Capital Company Private Limited, GMR Infrastructure Limited, and Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Limited.

Therefore, a majority of the investments from India to Africa are in the services sector – and within this, most can be attributed to the bilateral tax treaty between the two markets. Nonetheless, there are some complementarities with India’s bilateral trade trends, particularly in the case of resource-seeking investments in the mining and chemical industries. These trade and investments links can be strengthened under the AfCFTA.

Moreover, the above discussion highlights that India’s trade and investment interests in Africa are fairly diversified. The AfCFTA is thus likely to create opportunities for India with Africa by integrating it with global value chains, and within Africa by fostering trade linkages with different countries of the continent.

Challenges to Integration and Opportunities for India

There are challenges to both, integration within Africa as well as India’s integration with the continent. While inter-Africa tariff reduction may encourage inter-regional trade, certain key enablers are missing. The following paragraphs highlight some of these challenges and the opportunities that lie ahead for India.

Broadly, there are three crucial challenges: infrastructural bottlenecks; language and cultural challenges; and access to finance.

The infrastructural issues include lack of physical and digital infrastructure. The transportation infrastructure connecting African countries is weak and it is largely outward-oriented,[45] primarily towards the erstwhile colonies. The road connectivity networks are also fragmented and are inherited from the colonial period. According to the OECD, compared to other developing countries where the rate of road access is around 5 percent, Africa has a rate of 34 percent. [46] Other connectivity networks such as railways are non-existent in the region. Across the different African zones/unions, in many cases, there are no direct flights and internal air transport accounts for only 2-4 percent of the global air services market. To travel within Africa, often one has to travel through other continents to save time.[47] For instance, Mali and Burkina Faso share a long border but there are no direct flights from Bamako to Ouagadougou. Due to poor connectivity, intra-Africa transportation costs are higher by up to 100 percent. African nations rank among the lowest performers in the World Bank’s Logistics Performance Index.[48]

The success of the AfCFTA will depend largely on connectivity amongst the African countries, especially between the capital cities. There is a need for an inward focus on transportation development that should be conceived beyond international connectivity and transportation corridors.[49] One component of the African Union Agenda 2063 is the establishment of a Single African Air Transport Market (SAATM), which is aimed at transforming air connectivity within the continent. The Trans-Africa Rail Network is part of the Agenda 2063, however, the implementation is slow and results are yet to be seen. In the past, some of the large connectivity projects such as the Trans-African Highway Projects have failed to deliver, due to several reasons including lags in implementation.

There is also the challenge of limited market knowledge, as well as language, cultural and political barriers. Compounding these difficulties are information asymmetry, and the high transaction cost of doing business. One significant challenge is related to the cultural and ethnic diversities in Africa, which to a great extent is due to colonial history. Countries in Africa were occupied by different economic powers from Europe, including Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, and Spain. In most countries the official languages are different; in some countries English is not spoken at all; and across many countries there is no common language. This is a massive challenge both to African integration and India’s integration with Africa, as a unified market. While many African countries have ratified the Protocol on Free Movement of Persons, unless the language barrier is eliminated, the integration will remain merely on paper.

The third crucial challenge is limited access to finance. In the last few years, Africa’s trade finance has contracted by nearly 10 percent; due to the AfCFTA, the financial requirements have increased.[50] Moreover, due to a lack of foreign exchange liquidity in the local banks, trade finance requests of customers are often rejected.

It is also important to acknowledge competition. There has been a rise in Chinese investments in the infrastructure development in Africa since the turn of the new millennium. According to Sergio & Magrinya,[51] between 2001 and 2005, China’s development aid to Sub-Saharan Africa quadrupled. Between 2011 and 2013, China’s average lending commitment to African infrastructure projects was USD13.9 billion. In the subsequent year, nearly 15 percent of the total financial commitment for infrastructure development (including Africa’s own national budgets), was contributed by Africa. According to another estimate,[52] between 2000 and 2019, Chinese financiers signed 1,141 loan commitments worth USD153 billion with African governments and their state-owned enterprises. A majority of these are targeted towards infrastructure development including transportation and power. Chinese construction firms are also participating increasingly in construction and infrastructure development projects financed by fund banks. To that effect, the success of India leveraging AfCFTA may depend on the success of Chinese plans under its flagship Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). At present, Chinese companies also dominate the digital infrastructure sector, with a single Chinese company building over 50 percent of 3G networks and 70 percent of 4G networks in Africa.[53]

India has made some headway in developing transportation infrastructure in Africa through infrastructure financing and undertaking joint initiatives. There are existing initiatives such as the Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA), which is a partnership between the AUC, New Partnership for Africa’s Development Planning and Coordination Agency (NPCA), and the African Development Bank (AfDB). To fill the gaps, there is scope for private sector involvement through public-private-partnerships. Further, given the size and scale of infrastructure projects, India can also invest in project development and management services in the country to ensure successful implementation.

As regards international connectivity, over 90 percent of African trade is conducted by sea.[54] East African countries including the Seychelles and Madagascar are identified by the Indian Ministry of Ports, Shipping and Waterways (MoPSW) for the commencement of ferry services through inland waterways under the Sagarmala project. Other initiatives are underway. The Asia-Africa Growth Corridor is an economic cooperation agreement between India, Japan and Africa and was launched by the Indian government in 2017 with the vision of linking select Indian ports with those in Africa with the help of Japanese investments.[55] However, little progress has been made on the plan.

While many Indian telecommunication companies have invested in Africa, an area where India can collaborate with Africa is in the application of information and communication technologies. In the past few years, India has itself benefited from such application in areas such as agriculture, national identification, medical services, and more recently, in the field of education. Digital infrastructure can also be used to bridge the gap in the education sector, particularly given the diversity in Africa. In September 2020, for instance, India’s online learning platform—Digital Infrastructure for Knowledge Sharing (DIKSHA) – established by the Ministry of Education, was launched in Africa. A more structured approach has to be adopted by establishing formal inter-governmental cooperation programmes and getting private companies on-board. These could be prioritised as short-term opportunities in the market.

This also presents an area of opportunity for Indian businesses. So far, India’s investments in education services in Africa are limited. Some Indian companies such as Jain Global Education Services, JSS Education Foundation Limited, and Manipal Global Education Services Private Limited have made investments in Mauritius. More market-seeking investments are required in this sector, especially in establishing language training institutes in other African countries as this will also foster closer ties between the two markets. India can also partner with Africa in skills development, human resource management programmes, and entrepreneurship.

The private sector faces several challenges in the African continent and most companies operate without expanding their base to more than one or two African nations. There are ongoing initiatives to enhance trade partnerships between Africa and other countries including India. For instance, the United Kingdom’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) in partnership with the International Trade Centre (ITC) launched the Supporting India’s Trade Preferences for Africa’ (SITA) programme in 2014. One of the priorities under the programme is creating business linkages by sharing information, with the aim of greater trade diversification. There is a need to create public-sector and civil society institutions such as the India-Africa Trade Council that facilitate information and improve transparency.

From an Indian perspective, a number of ongoing projects in Africa are being financed through the line-of-credit, buyer’s credit and finance for joint ventures offered by the Export Import (EXIM) bank. The EXIM bank works closely with the AfDB group, supplementing the Government of India’s ‘Focus Africa’ Programme. Despite having large investments in the financial services sector in Africa, there are very few Indian banks present in Africa through bank branches. At present, most Indian banks have branches in Kenya (five branches), Mauritius (nine), Seychelles (one), and South Africa (five), while most banks have subsidiaries and representative offices.[56] Thus, the penetration of Indian banks in Africa is currently low.

Going forward, there is a need for greater financial sectors linkages between the two regions. In the long run, priorities under the Focus Africa programme of the Indian Government could be aligned with Africa’s Agenda 2063, clearly defining the short-, medium- and long-term priorities for the Indian Government to partner with Africa. This could then be used to mobilise development assistance towards implementation of the various initiatives under AUC Agenda 2063, which can also be complemented by private investments and blended finance.

Conclusion

The African Continental Free Trade Area is the result of an emerging ambition within the continent to become more self-reliant. Intra-Africa trade is low, and within regions, the inequalities are stark.

The AfCFTA can address these irregularities through the elimination of internal tariffs, among other things, thereby facilitating movement of raw materials and natural resources across Africa. This presents immense opportunities for countries with trade and investment linkages with Africa. India, for one, shares historical ties with Africa and the African Union is a large trade and investment partner for the country. However, much of this trade is concentrated with only a few African nations and investments are largely made to take advantage of the double-taxation agreements and are concentrated in the services sector.

This paper has outlined three key challenges that need to be addressed to harness the potential benefits of AfCFTA: One, infrastructure bottlenecks, specifically connectivity within Africa. There is need for better physical and digital connectivity between African countries and so far, India’s investments in this sector are low. Two, addressing language and cultural barriers that translate to limited market information. This is important in order for Indian companies to be able to look beyond English-speaking African nations. Three, access to finance through better financial sector penetration, complemented by private investments and blended finance.

India has a significant role to play in overcoming these challenges. It requires collaboration between the public and the private sectors in both India and Africa. Given the opportunities that the AfCFTA is likely to create for India, there is an inherent need for the country to accord priority to AfCFTA in its foreign policy map.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV