Introduction

Since the Soviet era, Russia has consistently experienced a high demand for labour. As its median age nears 40 (as of 2022),[1] Russia must increasingly contend with an ageing population and the resultant shortage of workers. In 2023, Russia reported a shortage of 4.8 million workers.[2] To address this issue, Russia relies heavily on migrant labour, particularly from the former Soviet republics, such as the Kyrgyz Republic, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan. In 2020, Russia had the world's fourth-largest migrant population, totalling 11.6 million.[3]

Labour migration in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS)[a] countries strongly correlates to their GDP per capita incomes. Labour migrants from Eastern Europe or the energy-rich Caucasian nations do not have a considerable role in Russia’s migrant labour market; most of Russia’s migrant workers are from the remittance-dependent Central Asian countries.[4] According to the 2020 CIS Statistics Committee, the wage rate in the Russian Federation is two times higher than in Uzbekistan and 3.5 times higher than in the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan; migrant workers from these countries earn between US$500 to US$800 a month in Russia.[5] These countries have a demographic dividend but have fewer job opportunities and offer low wages. As such, Russia became the preferred destination for migrants from Central Asia. However, the COVID-19 pandemic impacted migrant workers in Russia. For instance, lockdowns forced workers to return to their home countries due to a lack of jobs in the early stages of the pandemic. Although labour migration to Russia improved in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic, the war with Ukraine has now presented another challenge for migrant workers. Tougher working conditions determined by stringent laws governing migrant workers, the devaluation of the Ruble, which has impacted the value of remittances, apprehensions about working in the newly occupied territories, and coercion by Russian law enforcement agencies to sign military contracts are some of the issues migrant labourers must contend with while working in Russia.

In non-democratic migration regimes like Russia, informal power structures and extra-legal negotiations shape migration governance processes.[6] However, there is a gap in understanding the impact of the government’s immigration policies. As such, this paper assesses labour migration into Russia and the changing trends in the country’s foreign labour market. It also seeks to understand how the Ukraine conflict and other structural changes have impacted labour migration to Russia and how migrant workers have responded.

Survey of Russia’s Labour Market

Around 10 million people (predominately ethnic Russians) returned to Russia after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the 1990s. These migrants were either the victims of forced migrations during the Soviet era (1930-1952)[b] or were working in the Soviet republics, which became sovereign states post the dissolution.[7] There was a rapid growth in labour migration into Russia in the 2000s as its economy grew and the post-Soviet economies declined. Another reason for large-scale migration is Russia's visa-free border regime with the CIS countries. Over time, Russia became a crucial migration hub, but the political elite and society were unprepared to deal with the growing number of immigrants.

In 2002, Russia introduced its first migrant labour law (The Law on the Legal Status of Foreign Citizens in the Russian Federation) to regulate the flow of immigrants. The law introduced ethnic and cultural conditions that migrant workers had to fulfil to secure a residence permit and citizenship.[8] Since 2002, the country has introduced cumbersome measures such as migration cards, quotas for residence permits, visa-related procedures,[c] and registration at the place of residence and work. The law was amended in 2006, simplifying the legalisation process for immigrants, giving migrant workers the choice to either apply for a work permit (which would enable them to switch employers) or secure a work permit through the employer. The Federal Migration Service (FMS) determined the number of work permits to be issued based on the labour demand. The number of documented migrants increased from 570,000 in 2006 to 2.4 million in 2008. Half of these permits were issued to workers from Tajikistan, the Kyrgyz Republic, and Uzbekistan.[9]

In the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, the flow of migrants declined to about 20 percent; the FMS reduced the quotas from six million in 2007 to 3.8 million in 2008.[10] As the Russian economy rebounded, the quotas were increased, but there was a year-on-year decline in the number of quotas issued. This was primarily due to bureaucratic hurdles, such as excluding small business owners and entrepreneurs. The patent (out-of-quota work permit system) was introduced to incorporate smaller-scale employers, followed by adding a chapter on the employment of foreign citizens in the Russian labour code in 2014. In 2015, work permits were replaced with patents, which became the sole document necessary for foreign labourers to work in Russia. The same year, Russia abolished its 90-day exit rule, which required workers from the CIS countries to exit Russia after 90 days before re-entering. Notably, although the number of patents issued declined, the number of migrants from the CIS countries increased. In 2021, 2.2 million patents were issued to labourers; in 2022, it was closer to two million.[11] During the first three months of 2023, 1.4 million patents were issued.[12] However, the number of migrants in Russia was much higher (see Table 1). As undocumented migration grew, the number of restrictions and amendments to the labour laws also increased.

While Russia has between nine million and 11 million migrants, the actual number is likely closer to 18 million when also accounting for illegal immigrants.[13] This is because of Russia's visa-free regime with most CIS countries and the cumbersome patent registration process, which results in most workers entering Russia and working illegally. As of 2023, Russia has over 10 million foreign workers,[14] with most located in cities such as Moscow, Novosibirsk, Krasnodar, St. Petersburg, Tyumen, and Yekaterinburg.

Table 1: Number of migrant workers in the Russian Federation registered at the place of stay (2019-2021)

|

Number of Migrants registered at the place of stay |

Number of Migrants registered at the place of stay for the purpose of work |

|

2019 |

2020 |

2021 (January-June) |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 (January-June) |

| Total |

18,951,004 |

9,340,798 |

4,972,497 |

5,478,249 |

2,358,827 |

3,654,462 |

| From Central Asian Countries |

9,504,176 |

6,409,267 |

3,538,920 |

3,881,448 |

1,772,962 |

2,971,637 |

| Percentage Share of Central Asian Countries |

50.1 |

68.6 |

71.2 |

70.9 |

75.2 |

81.2 |

| Uzbekistan |

4,739,789 |

3,404,660 |

1,841,595 |

2,107,302 |

1,011,028 |

1,685,166 |

| Tajikistan |

2,652,867 |

1,829,270 |

1,017,505 |

1,179,423 |

507,255 |

828,125 |

| Kyrgyz Republic |

1,039,374 |

722,880 |

456,085 |

453,702 |

190,312 |

384,833 |

| Kazakhstan |

692,840 |

368,619 |

199,584 |

136,208 |

60,461 |

70,199 |

| Turkmenistan |

121,848 |

83,838 |

24,151 |

4,813 |

3,906 |

3,314 |

Source: International Organisation for Migration [15]

The growth in the Russian economy saw the rapid expansion of the service sector; the percentage of women workers participating in domestic work and the service sector surged from 41 percent in 1995 to 62 percent in 2015.[16] Women migrant workers generally arrive in Russia alongside their spouses, who are also workers. In 2019, most of the women migrants to Russia were from Ukraine (28 percent), Kazakhstan (13.7 percent), Uzbekistan (12.2 percent), Tajikistan (12.1 percent), Armenia (7.9 percent), and the Kyrgyz Republic (7.8 percent).[17]

Labour regulation regime

Although people from the CIS countries can enter Russia without a visa, they need a work permit (or patent) to work there. Given the rise of illegal migration, Russia has tightened its labour-related regulations in recent years. For instance, between 2012 and 2015, the country adopted 50 laws to reduce undocumented migrations,[18] enforced through criminal and administrative penalties. In 2013, entry bans were introduced, restricting the re-entry of anyone found to be an illegal migrant for three to 10 years.

Since 2015, migrant workers have had 30 days to obtain a patent. An individual would have to undergo an exam ascertaining language fluency and awareness of Russian law and culture, get medical insurance, and pay the first month’s taxes, along with a monthly fee for the patent; this amounts to a one-time fee of around 30,000 rubles (US$350),[19] which may be exorbitantly high for most migrants. The rules even mention that workers have to live in the place of residence given, and restrictions have been set on the number of people who can live in a space. Such tedious and bureaucratic laws are introduced to disincentivise unskilled migration into Russia.

Over the years, the FMS has been granted significant powers; it is a law enforcement body with extrajudicial powers to curb illegal migration.

One reason Russia’s migration regime is so tightly regulated is perhaps the rising anti-migrant sentiments in local society. For instance, one survey found that two-thirds of Russians wanted politicians to curb migration. The intense migration to Europe triggered by the Syrian refugee crisis has further exacerbated negative attitudes towards migrants.[d],[20] As such, the Kremlin elite are not tolerant of non-Russian labour.[21]

Impact of Ruble devaluation

In the first devaluation of the Ruble caused by the imposition of sanctions following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, the official migrant labour force in Russia declined from 3 million to 1.8 million in 2015.[22] Migration from Tajikistan and Uzbekistan to Russia declined by 22.2 percent and 15.6 percent, respectively, in 2015.[23] The situation stabilised as more patents were granted to workers. However, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the Russian central bank imposed capital control laws and raised the interest rate from 9.5 percent to 20 percent[24] to stop capital flight and stabilise the Ruble. Further, Russian firms were barred from transferring foreign money overseas and faced a six-month cap on amounts withdrawn from Russian banks. Russian firms receiving payments in foreign currencies had to convert 80 percent of those earnings into Rubles. As a result, the Russian economy could withstand shocks from Western sanctions in the first year of the invasion.[25]

However, devaluation began to take shape in 2023. In August 2023, the exchange rate for US$1 crossed 100 Rubles; the rise in military spending, collapse in export revenues due to sanctions, and escalation of capital outflows resulted in a substantial Ruble devaluation. Since 2023, the Ruble’s exchange rate against the Kyrgyzstani Som fell by 22 percent, 18 percent against the Uzbekistani Som, and 25 percent against the Armenian Dram and the Kazakh Tenge. This sort of devaluation makes migration to Russia less desirable. This has impacted the remittances to many of the main migrant-providing countries. For instance, remittances account for over 32 percent of Tajikistan’s GDP (2023)[26] but the decline in remittances saw the GDP growth rate decelerate from 8 percent in 2022 to 6.5 percent in 2023. In Uzbekistan, the contribution of remittances to GDP has declined from 21 percent in 2022 to 18 percent in 2023. In the Kyrgyz Republic, the volume of remittances decreased by 14 percent, from US$2.94 billion in 2022 to US$2.51 billion in 2023.[27] On the other hand, Kazakhstan’s GDP is not highly dependent on remittances from Russia; in fact, the country is experiencing a growth in Russian migrants.[28]

Impact of the pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic was another stressor for migrant workers in Russia. The volume of transfers through payment systems to former Soviet countries at the height of the pandemic in April 2020 was 1.7 times lower than in April 2021.[29]

An overcentralised state decentralised pandemic management, giving regional governors the authority to determine when to impose lockdowns. This resulted in different regions having different laws on managing the pandemic, impacting migrant workers significantly. For instance, if a patent were issued to a worker in Moscow, it would only be valid for that city. If the worker found a better job in St. Petersburg, they would have to spend another US$400 and restart the process. Therefore, during the pandemic, many workers were forced to work illegally, and the police did not intervene because of the huge demand for labour.[30] The closing of borders and cancellations of flights resulted in migrant workers being stuck in Russia. Over one million workers from Uzbekistan, 500,000 from Tajikistan, and 350,000 from the Kyrgyz Republic were among the 4.2 million workers stuck in Russia during the pandemic.[31]

Key Challenges for Migrant Labourers in Russia

Apart from the legal challenges, migrant labourers in Russia face some internal challenges, which, over time, will add to the economic stresses and can disincentivise workers from seeking or sustaining employment in Russia.

Legal and Social Issues

A critical challenge many migrant labourers must confront is excessive policing in Russian cities. The police often hold inspections at metro stations or shared living spaces to check the validity of patents. Many migrant workers live in cramped apartments, sharing the space with others even though the registration permits only two people to live in a single space. These are grounds for deportation. Additionally, if their patent has expired or does not fulfil the preconditions, they could receive an entry ban (five to 10 years) upon deportation. Furthermore, many younger migrant workers are not fluent in the Russian language, which could create an issue in securing good jobs and dealing with police and other officers. As a result, they may need to use pośrednik (intermediary) to find employment.[32]

Amendments to migrant-related rules and rigid law enforcement is a significant hurdle for migrant workers. As such, becoming ‘legal’ or ‘illegal’ may depend on contextual factors[33] (such as the time, space, and circumstances of encounters with the law). To circumvent such state coercion, the workers turn to their local (village or country) networks in Russia,[34] resulting in a reliance on a ‘shadow economy’. Migrants have a trust deficit in the legal system and often rely on informal and illegal channels. When entry bans are issued, migrant workers rely more on their networks and intermediaries than the courts. Migrants pay a bribe to the registratsiyachi (a residence registration intermediary) to temporarily suspend their entry bans, during which they can legally re-enter Russia and obtain a new patent. After the ban is reinstated, the worker remains untraceable by the police and FMS. Migrants also rely on various extralegal documentation schemes run by immigration officials, police, border control officials, lawyers, activists, and immigration consultancy firms.[35]

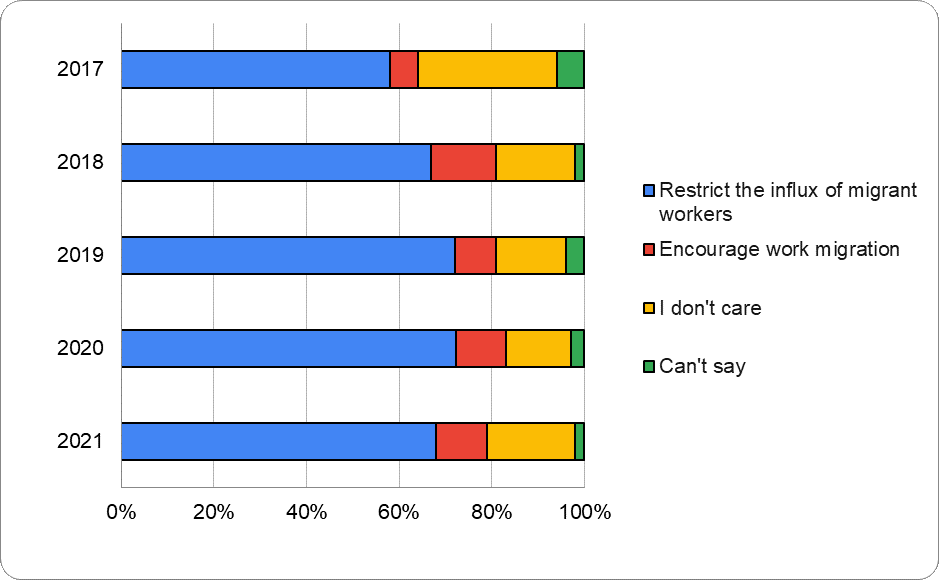

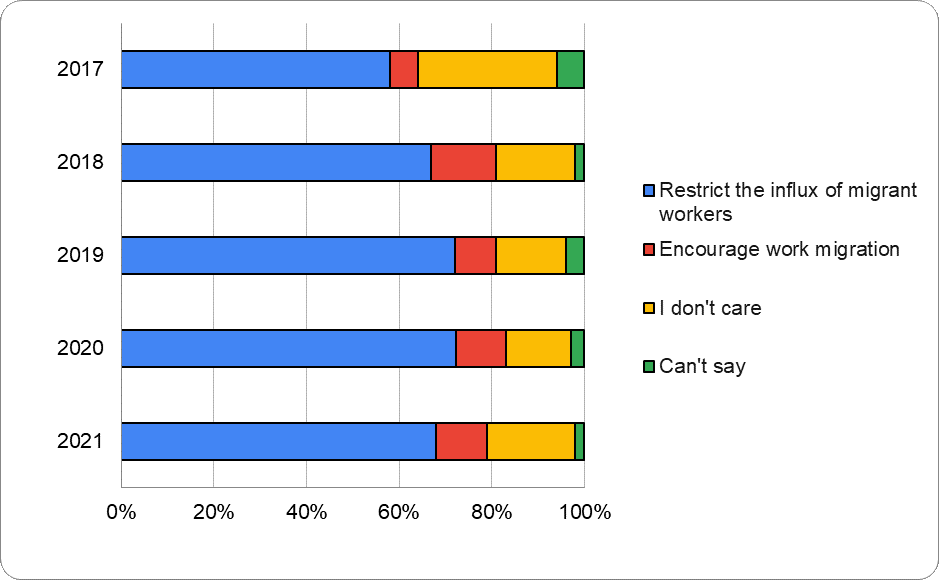

Xenophobia is also on the rise in Russian society and politics. Migrant workers are depicted as gasterbaitery (a German word for guest workers, used with a negative connotation in Russia to mean illegal). Migrants are assumed to be eager to commit crimes, and such racist narratives are disseminated by the media, stoking anti-migrant sentiments. For instance, a 2020 poll found that 73 percent of Russians had an unwelcoming attitude towards migrants (see Figure 3).[36] Russian President Vladimir Putin has also stated that the country should adopt a ‘selective approach’ to immigration policies, welcoming only those who are aware of Russian culture and speak the language (this would mean only migrants from Slavic nations, such as Belarus, Moldova, or Ukraine, or those with a Slavic heritage).[37]

Figure 3 Opinion on Potential Policies Related to Migrant Workers

Note: The graph represents responses to the question: “What Policy do you think the Russian government should follow concerning migrant workers?”

Source: Levada Centre[38]

Women migrant workers face additional discrimination based on their gender and ethnicity. Women are often employed in the lowest-paying jobs in the service and hospitality sectors, with little job security. They also face the risk of sexual coercion and violence. In a pan-Russia survey of 442 migrant women workers, 100 percent of those working in the entertainment industry and 20 percent in the retail sector said they had been forced to provide sexual services.[39]

In recent months, many migrant workers who were apprehended by law enforcement officers have been coerced by the FMS and police into signing military contracts to work as helpers in the Russian army with the promise of gaining Russian citizenship. Many workers fear that signing these contracts will result in being deployed to fight in Ukraine. Some migrants attempt to flee the country after acquiring Russian citizenship during the two-week grant period given to new citizens before joining the military.[40] In such cases, their citizenship can be revoked.[41] Apart from warfighting, signing military contracts could mean working in Russian-occupied regions in Ukraine as porters and on infrastructure development projects.[42]

Labour Migration Trends Since 2022

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 did not result in an immediate decline in the number of migrant workers in the country, which can be attributed to the social and economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, with many workers seeking to replace lost incomes from the pandemic years (especially since the Ruble had not devalued due to the intervention of the Bank of Russia). However, labour migration declined in the first half of 2023 by 40 percent compared to the first half of 2022 amid the Ruble devaluation.[43] Ukrainian labour migration has naturally declined since the conflict began. In Moldova, a significant chunk of migrants are choosing to learn the German language and to work in Germany rather than in Russia.[44] The number of workers from Kazakhstan, Georgia, and Azerbaijan has also declined because of the high degree of economic growth, employment, and education standards in those countries.[45] At the same time, the number of migrants from Uzbekistan,[47] Tajikistan,[48] and the Kyrgyz Republic[49] continues to increase. Given Russia’s rigid migration regime and the devaluation of the Ruble, workers are looking to other countries for employment. This trend will persist if the Russian economy remains volatile and anti-migrant sentiments persist stance persists.

For instance, Uzbekistan has cooperated on labour migration with Türkiye, the UK, and the Baltic states. Türkiye is becoming a lucrative destination for Central Asian female migrants, who are employed in the hospitality and services sector and earn substantially more than male Central Asian migrants.[50] Despite comparatively lower wages than in Russia, the migrant-friendly immigration regime and the liberal labour laws make Türkiye a lucrative destination. Uzbekistan has also held discussions with Goldcliff Stark, an international labour law firm based in Germany, to provide labour assistance by employing Uzbek workers.[51] The EU's 2019 Action Strategy for Central Asia aims to boost migration cooperation, shifting focus from security to expanding labour migration beyond Russia. This move aligns with broader strategies to reduce Russia's influence by limiting its access to Central Asian labour.[52] Uzbekistan has also signed similar agreements with Israel and Saudi Arabia. The Kyrgyz government has also signed an agreement with the South Korean Human Resource Development Service to create 5,000 job openings for Kyrgyz citizens in South Korean companies.[53]

Additionally, Kazakhstan is emerging as a new potential destination for migrant workers. The average wage in Kazakhstan is US$720 per month, which is set to rise in the coming years.[54] Astana attracts labour migrants from the Kyrgyz Republic,[55] Uzbekistan,[56] Tajikistan,[57] and Russia; about 10 percent of the 724,534 International migrants in Kazakhstan are from Russia, as of the first quarter of 2023.[58]

Central Asian governments are cautious when dealing with Russia. They do not want to outrightly discourage immigration to Russia as they do not have adequate employment opportunities for their workers (this is especially true in countries that are highly dependent on Russia for their remittances). As such, many have discouraged their citizens from accepting Russian citizenship and fighting in Ukraine,[59] but to a limited degree.

Another noticeable trend is that migrant labourers opt not to work in Russia’s colder regions and northern cities (this could explain the labour shortage during the winter months[60]). Some regions (such as Nizhny Novgorod, Tula, Samara, Novosibirsk, and Ekaterinburg) have seen a higher demand for labour since the start of the war as they have many defence industries.[61] With defence industries expanding, the Russian government is trying to incentivise labour migration because of labour shortages. Workers from the civilian sector have shifted to the defence industries to satisfy the increased labour demand there, resulting in a labour shortage in the civilian sectors (such as manufacturing and the agro-industrial complex).[62]

The Ukraine conflict and sanctions on Russia have resulted in an increased number of Russians working for the federal government. The Republics of Buratiya, Altai Krai, Altai, Chechnya, and Dagestan have seen the fastest income growth for low-income groups,[63] primarily because individuals from these groups are now employed by the Russian armed forces, with substantial funds disbursed to the families of the wounded and deceased. This indicates that the economy is highly dependent on the State, and the State, in turn, is dependent on the revenue generated from Russian energy.[64] While this is sustainable for the local population, it disincentivises migrant labourers from working in Russia as the remittance value will shrink.

Notably, Central Asian countries are seeking to structurally reform their economies and move away from traditional growth-based strategies of commodity and labour exports to generate economic growth. In pursuit of such strategies, these countries would have a massive demand for labour. Consequently, in 2023, Uzbekistan implemented state employment programmes to encourage youth employment and reduce the outflow of labour.[65] The Kyrgyz Republic has adopted similar programmes.[66]

Although Russian society is most conducive to those with a high fluency in the Russian language, there is a significant volume of skilled migration from non-CIS countries. Most skilled professions are outside the realm of the patent requirement and are covered by work permits. In 2021, 15.7 percent and 31.5 percent of the total work permits were granted to Vietnamese and Chinese citizens, respectively.[67] Although there has been some decline in labour migration from non-CIS countries, the trend of skilled migration from these countries continues.[68]

The number of Indian migrants to Russia has also increased, with some firms hiring unskilled workers (such as packers, container assemblers, and production line operators).[69] However, it is difficult to ascertain the exact number of such workers as many enter Russia illegally on a tourist visa and do not have the language proficiency required to acquire a patent. There have been some reports that Indian workers were coerced into signing military contracts with the Russian army and fighting in the Ukraine war.[70] Subsequently, the Indian government issued a warning to Indian citizens to avoid signing military contracts and began pursuing the early discharge of the Indians working in the Russian army.

Conclusion

Migrant labour is a critical asset for Russia. Since 2022, the birth rate has declined by 3.2 percent. Additionally, the population declined by 17.2 percent in 2023 as compared to 2022 levels.[71] Russia’s median age is 40, and trends indicate the average age will rise—not fall—in the future. As such, migration is a panacea for the country’s declining population problem; a 2023 poll indicated that 47 percent of Russians now favour migration (the survey did not reveal any preferred nationality).[72] To encourage migrant labourers to come to the country and spread awareness about labour laws, Russia aims to develop a digital platform containing learning materials to assist foreign citizens in learning the Russian language and adapting to the Russian way of life.[73] The government has also eased the norms for work permits to encourage high-skilled workers to migrate to Russia, but there are still no changes to the patent system.[74]

In the short term, labour migration to Russia may increase due to the high wages offered in military-intensive industries. In the long term, if the conflict with Ukraine persists, the value of the remittances will decline. Additionally, extensive legal and bureaucratic hurdles arising from a reluctance to allow migrants into the country to avoid the ‘hybridisation’ of Russian society will make securing jobs and living in Russia more difficult for migrant workers. Nevertheless, the demand for labour will remain high, and how Russia navigates meeting this need even as it seeks to protect its culture will be noteworthy.

The author thanks Vaishali Jaipal, ORF Research Intern, for assisting with preparing the final graphs.

Endnotes

[a] The CIS was formed after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, and focuses on political, economic, environmental, humanitarian, cultural, and other important issues among the former Soviet Republics. Its nine full members are Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

[b] In the immediate aftermath of the end of the Soviet Union, over 25 million Russians lived in the newly formed countries. Several social and ethnic groups were deported to the Caucasian and Central Asian Republics between 1930 and 1952. Although many relocated after Stalin’s death, numerous Russians lived in these republics.

[c] Under the visa-free regime, migrant workers had to leave Russia after 90 days but could sometimes not re-enter for a stipulated period of time.

[d] Increased migration by Muslim refugees to Europe saw a rise in anti-immigrant sentiments, including in Russia. As Europe becomes more multicultural because of migration, Russia has focused on protecting its Slavic heritage and traditions, and is averse to accept migrants who do not understand the Russian way of life.

[1] Federal State Statistical Service (Rosstat): Demographic Yearbook of Russia 2023, Moscow, Russian Federation, 2023, https://rosstat.gov.ru/folder/210/document/13207

[2] “Russia short of around 4.8 million workers in 2023” Reuters, December 24, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russia-short-around-48-million-workers-2023-crunch-persist-izvestia-2023-12-24/

[3] IOM “Migration data platform for Evidence-Based Regional Development- Russian Federation,” https://seeecadata.iom.int/msite/seeecadata/country/russian-federation,” IOM UN Migration.

[4] Rustamjon Urinboyev and Sherzod Eraliev, The Political Economy of Non-Western Migration Regimes: Central Asian migrants in Russia and Turkey (Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2022), pp.5

[5] Daria Nikitskaya, “The salaries of Guest Workers in Russia have been revealed: we caught up with the Russians,” Moscovskiy Komsomolets, December 12, 2021, https://www.mk.ru/economics/2021/12/14/raskryty-zarplaty-gastarbayterov-v-rossii-dognali-rossiyan.html

[6] Rustamjon Urinboyev and Shezod Eraliev, The Political Economy of Non-Western Migration Regimes: Central Asian migrants in Russia and Turkey

[7] Hilary Pilkington and Moya Flynn, “A Diaspora in Diaspora? Russian Returnees Confront the Homeland”. Refuge: Canada’s Journal on Refugees, 23(2), 55-67, (2006) https://doi.org/10.25071/1920-7336.21355

[8] Russian Federation, The Ministry of Foreign Affairs: “Federal Law Concerning the Legal Status of Foreign Citizens in the Russian Federation,” Moscow, 2002, https://mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/fundamental_documents/1586163/

[9] Zhanna Zayonchkovskaya and Elena Tyuryukanova (eds) Migration and Demographic Crisis in Russia (migratsiia i demograficheskii krizis v Rossii). INP RAS (2010)

[10] Mikhail Denisenko and Evgeniia Chernia, “Migration of Labor and Migrant Incomes in Russia,” Problems of Economic Transition, 59(11-12), 896-908, (2018)

[11] Federal State Statistical Service, Russian Statistical Yearbook 2023, Moscow, Russian Federation, 2023,

[12] Federal State Statistical Service: Information on Migration Situation in the Russian Federation, Moscow, Russian Federation, 2022

[13] Caress Schenk, “Counting Migrants in Russia: The Human Dimension of Administrative Data Production,” International Migration Review, (2023)

[14] “Putin said that there are about 10 million labour migrants in Russia,” TASS, December 14, 2023, https://tass.ru/obschestvo/19539345

[15] Sergey Ryazantsev, Aygul Sadvoksova, and Jamilia Jeenbaeva, “Study of Labour Migration Dynamics Dynamics in the Central Asia – Russian Migration Corridor Consolidated Report,” Moscow, International Organisation for Migration, 2021, https://russia.iom.int/resources/study-labour-migration-dynamics-central-asia-russian-federation-migration-corridor-consolidated-report-2021

[16] International Labour Organization, Women at work, trends 2016, International Labour Office, Geneva, 2016, https://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv:72419

[17]Veronika Romanenko and Olga Borodkina, “Female Immigration in Russia: Social Risks and Prevention,” Jounal of Human Affairs, 29(2), 174-187, (2019), https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/humaff-2019-0014/html?lang=en#j_humaff-2019-0014_ref_024

[18] Mikhail Denisenko, “Migration to Russia and the Current Economic Crisis,” Migration and Ukraine Crisis, 129, (2017)

[19] Sherzod Eraliev and Rustamjon Urinboyev, Precarious Times for Central Asian Migrants in Russia

[20] Ilya Budraitskis, Denys Gorbach, “Dreams of Europe: refugees and xenophobia in Russia and Ukraine,” open Democracy, February 10, 2017, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/odr/dreams-of-europe-refugees-and-xenophobia-in-russia-and-ukra/

[21] David Priestland, “Exploiting xenophobia is bad politics for Putin,” Financial Times, November 18, 2013, https://www.ft.com/content/20dbed28-4c80-11e3-923d-00144feabdc0

[22] Caress Schenk “Post-Soviet Labour Migrants in Russia Face New Questions amid War in Ukraine,” Migration Policy Institute, 7 February, 2023, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/labor-migrants-russia-ukraine-war-central-asia

[23] Sherzod Eraliev and Rustamjon Urinboyev, “Precarious Times for Central Asian Migrants in Russia,” current history, vol. 119, (819), pp 258-263 (2020), http://hdl.handle.net/10138/321040 10.1525/curh.2020.119.819.258

[24] Rajoli Siddharth Jayprakash, “Riding the storm: Russia’s economic landscape since the Ukraine conflict,” Observer Research Foundation, February 28, 2024, https://www.orfonline.org/research/riding-the-storm-russias-economic-landscape-since-the-ukraine-conflict

[25] Alexandra Prokopenko, “Is the Kremlin Overconfident About Russia’s Economic Stability,” April 10, 2024, https://carnegieendowment.org/2024/04/10/is-kremlin-overconfident-about-russia-s-economic-stability-pub-92174#_edn12

[26] Aurthur Arutyunov, “The ripples of the Ruble how the collapse of the currency could impact its neighbours and cause a damaging decline in labour migrations, Meduza, August 31st 2023, https://meduza.io/en/feature/2023/08/31/the-ripples-of-the-ruble

[27] “Remittances to Kyrgyzstan from the Russian Federation in 2023 decreased by 14%,” Interfax, 16 February, 2024,

https://www.interfax.ru/world/946470

[28] Joanna Lillis, “Kazakhstan: New migration rules to hit Russians fleeing the draft,” Eurasianet, January 17, 2023, https://eurasianet.org/kazakhstan-new-migration-rules-to-hit-russians-fleeing-the-draft

[29] Mikhail Denisenko and Vladimir Mukomel, “Labour Migration in Russia During the Coronavirus Pandemic,” Демографическое обозрение, 7(5), 42-62, (2020)

[30] Rustamjon Urinboyev and Shezod Eraliev, The Political Economy of Non-Western Migration Regimes: Central Asian migrants in Russia and Turkey

[31] Sherzod Eraliev and Rustamjon Urinboyev, Precarious Times for Central Asian Migrants in Russia

[32] Madeleine Reeves, “Diplomat, Landlord, Con-artist, Thief: Housing Brokers and the Mediation of Risk in Migrant Moscow,” The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology, 34(2), 93-109, (2016)

[33] Caress Schenk, “Producing state capacity through corruption: the case of immigration control in Russia,” Post-Soviet Affairs, 37(4), 303-317, (2021)

[34] Madelene Reeves, “Living from the Nerves: Deportability, Indeterminacy, and the ‘Feel of Law’ in Migrant Moscow,” Social Analysis 59(4), 119-136, (2015)

[35] Rustamjon Urinboyev, Migration and hybrid political regimes: Navigating the legal landscape in Russia, University of California Press, (2020)

[36] “Xenophobia is Still on the Rise in Russia-poll,” Moscow Times, September 18, 2019, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2019/09/18/xenophobia-is-still-on-the-rise-in-russia-poll-a67326

[37] Sherzod Eraliev and Rustamjon Urinboyev, Precarious Times for Central Asian Migrants in Russia

[38] “Xenophobia and Migrants,” Levada Centre, January 28, 2022, https://www.levada.ru/en/2022/01/28/xenophobia-and-migrants/

[39] Veronika Romanenko and Olga Borodkina, “Female Immigration in Russia: Social Risks and Prevention”

[40] “Migrants Reportedly Being Forced To Sign Contracts with Defense Ministry To Obtain Russian Citizenship,” Radio Free Europe, August 28, 2023, https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-central-asia-migrants-military-recruitment-ukraine/32567862.html

[41] “In Russia, a law on termination of citizenship for discrediting the army came into force,” TASS, October 26, 2023, https://tass.ru/obschestvo/19117249

[42] Jake Cordell, “Falling Ruble Dents Russia’s image Among Central Asian Migrant Workers,” Moscow Times,

September 13, 2023, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2023/09/13/falling-ruble-dents-russias-image-among-central-asian-migrant-workers-a82418

[43] Iryna Ivakhnyuk, “Labour Migration to Russia: A view through the Prism of Political, Economic and Demographic Trends,” Russia international Affairs Council, November 17, 2023, https://russiancouncil.ru/analytics-and-comments/analytics/trudovaya-migratsiya-v-rossiyu-vzglyad-cherez-prizmu-politicheskikh-ekonomicheskikh-i-demografichesk/

[44] Tatiana Tabac and Olga Gagauz, “Migration from Moldova: Trajectories and Implications for the Country of Origin,” in Migration from the Newly Independent States, 25 after the collapse of the USSR, ed. Mikhail Denisenko et al, Springer, (2020)

[45] Caress Schenk, “Post-Soviet Labour Migrants in Russia Face New Questions amid War in Ukraine”

[46] “EEC: Labour Migration between Belarus and Russia has returned to pre-Covid levels,” Belata, March 10, 2023, https://www.belta.by/society/view/eek-trudovaja-migratsija-mezhdu-belarusjju-i-rossiej-vernulas-na-dokovidnyj-uroven-554640-2023/

[47] “Influx of labour migrants from Uzbekistan to Russia increased by 35.1% over the last year,” KUN.UZ, https://kun.uz/en/news/2023/02/20/influx-of-labor-migrants-from-uzbekistan-to-russia-increased-by-351-over-last-year

[48] “Migration from Tajikistan to Russia is growing rapidly despite the war,” Central Asian Bureau for Analytical Reporting, May 22, 2023, https://cabar.asia/ru/migratsiya-iz-tadzhikistana-v-rossiyu-bystro-rastet-nesmotrya-na-vojnu

[49] Daniyar Karimov, “The number of labour migrants from Kyrgyzstan has increased in Russia,” Rossiyskaya Gazeta, March 22, 2023, https://rg.ru/2023/03/22/chislo-trudovyh-migrantov-iz-kyrgyzstana-v-rossii-vyroslo.html

[50] Rustamjon Urinboyev and Shezod Eraliev, The Political Economy of Non-Western Migration Regimes: Central Asian migrants in Russia and Turkey

[51] Rustam Temirov, “Eschewing Russia, Uzbek migrants seek new labour markets in Europe,” Caranvanserai, June 17, 2023, https://central.asia-news.com/en_GB/articles/cnmi_ca/features/2023/07/17/feature-01

[52] Ivakhyuk “Labour Migration to Russia: A view through the Prism of Political, Economic, and Demographic Trends”

[53] Yan Matusevich, “From Samarkand to Seoul: Central Asia migrants in South Korea,” Eurasianet, May 17, 2019, https://eurasianet.org/from-samarkand-to-seoul-central-asian-migrants-in-south-korea.

[54] International Organization for Migration, “Overview of the Migration Situation in Kazakhstan,” UN migration, 2022, https://reliefweb.int/report/kazakhstan/overview-migration-situation-kazakhstan-quarterly-report-january-march-2023

[55] “Aiman Nakispekova, “Central Asia Responds to Shifting Migration Dynamics,” The Astana Times, 19 April, 2024, https://astanatimes.com/2024/04/central-asia-responds-to-shifting-migration-dynamics/

[56] “Kazakhstan Replaces Russia As Destination For Uzbek Migrants,” Times of Central Asia, March 25, 2024, https://timesca.com/kazakhstan-replaces-russia-as-destination-for-uzbek-migrants/

[57] “Tajikistan: Migrant labourers seeking alternatives to Russia,” Eurasianet, June 8, 2023, https://eurasianet.org/tajikistan-migrant-laborers-seeking-alternatives-to-russia

[58] “International Organization for Migration, “Kazakhstan-International Migrant Workers Survey-Round 2,” UN migration, 2023, https://dtm.iom.int/datasets/kazakhstan-international-migrant-workers-survey-round-2

[59] Colleen Wood and Sher Khashimov. “Central Asians in Russia Pressured to Join Moscow’s Fight in Ukraine,” The Moscow Times, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2022/03/17/central-asians-in-russia-pressured-to-join-moscows-fight-in-ukraine-a76957

[60] Temur Umarov, Fellow, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, WhatsApp message to the author, 05-01-2024

[61] Alexandra Prokopenko, “Putin’s Unsustainable Spending Spree: How the War in Ukraine Will overheat the Russian Economy,” Foreign Affairs, January 8, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/russian-federation/putins-unsustainable-spending-spree

[62] Anastasia Manuilova, “India will help us: companies are looking for employees in distant countries,” Kommersant, Jaunary 2, 2024, https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/6480459

[63] Alexandra Prokopenko, “Putin’s Unsustainable Spending Spree: How the War in Ukraine Will overheat the Russian Economy.”

[64] Alexandra Prokopenko, “Is the Kremlin Overconfident About Russia’s Economic Stability,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, April 10, 2024, https://carnegieendowment.org/2024/04/10/is-kremlin-overconfident-about-russia-s-economic-stability-pub-92174#_edn12

[65] Kakoeva Nadezhda Anatolyevna, “Eurasian migration system, current trends and development prospects,” Russia International Affairs Council, 2023, https://russiancouncil.ru/papers/Conference-Report-EurasianMigration.pdf

[66] “16.7 thousand unemployed citizens were employed in Kyrgyzstan in 2023,” KABAR, February 2, 2024, https://en.kabar.kg/news/16.7-thsd-unemployed-citizens-were-employed-in-kyrgyzstan-in-2023/

[67] Federal State Statistical Service (Rosstat): Russian Statistical Yearbook 2022

[68] Federal State Statistical Service (Rosstat): Russian Statistical Yearbook 2022

[69] Manuilova, “India will help us: companies are looking for employees in distant countries”

[70] Srinivas Janyala and Bashaarat Masood, “Job hunt, Youtube channel, false promises- how Indian youths landed on Russia-Ukraine war frontlines,” The Indian Express, March 6, 2024, https://indianexpress.com/article/long-reads/job-hunt-youtube-false-promises-indian-youths-russia-ukraine-war-frontlines-9195920/

[71] ”Putin sets task to achieve steady rise in births in Russia within next six years,” TASS, Feburary 29, 2024, https://tass.com/society/1753719

[72] “Immigrants in Russia: Pro et Contra,” VTSIOM, August 14th, 2023, https://wciom.com/press-release/immigrants-in-russia-pro-et-contra

[73] “Mikhail Mishustin chairs strategic session on migration policy,” The Russian Government, October 24, 2023, http://government.ru/en/news/49873/

[74] Caress Schenk, “Post-Soviet Labour Migrants in Russia Face New Questions amid War in Ukraine”

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV