Introduction

The South Asian Association of Regional Cooperation (SAARC) has come under serious scrutiny in the last few years. Even after three decades of its existence, SAARC’s performance has been less than satisfactory, and its role in strengthening regional cooperation is being questioned. At the 18th SAARC summit in Kathmandu in 2014, initiatives such as the SAARC–Motor Vehicle Agreement (MVA)—crucial for harnessing regional connectivity across South Asia—could be not signed due to Pakistan’s dithering. SAARC faced another setback after the 19th summit scheduled to be held in Pakistan in 2016 was suspended for an indefinite period, as member countries declined to participate, pointing to what they said was the absence of a conducive regional environment.

Recently, the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) has gained more favour as the preferred platform for regional cooperation in South Asia. After India hosted a mini-summit during the BRICS meeting in Goa in 2016, support for BIMSTEC gained further momentum. By comparing BIMSTEC and SAARC, this brief explores the efficacy of BIMSTEC as a platform for regional cooperation in the South Asian context. The brief also highlights the problems in both organisations and the corrective measures required to strengthen them.

The Failures of SAARC

SAARC has eight member countries: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. While the organisation was intended to enhance regional cooperation in South Asia, from its very inception, member countries treated it with suspicion and mistrust.

SAARC was first envisioned in the late 1970s by Gen. Ziaur Rahman, the military dictator of Bangladesh. Initially, India was apprehensive about SAARC because it perceived the grouping to be an attempt by its smaller neighbours to unite against it. The Cold War politics of the time, too, contributed to India’s anxiety.[1] India had a close relationship with the Soviet Union, and it considered Ziaur Rahman to be aligned with the West. It was, therefore, suspicious that SAARC could be an American mechanism to counter Soviet influence in the region. It feared that the association might lead to Asia’s own Cold War, creating a pro-Soviet–anti-Soviet rift. This would have played against India’s interest since it had close strategic ties with the Soviet Union.[2]

Eventually, India agreed to join SAARC due to the interest expressed by the neighbouring countries. The first SAARC meeting took place in Dhaka in 1985, and there have been 18 summits till date. However, the organisation has not had a smooth run. In the 30 years of its history, annual SAARC summits have been postponed 11 times for political reasons, either bilateral or internal.[3]

SAARC is aimed at promoting the welfare of the people; accelerating economic growth, social progress and culture development; and strengthening collective self-reliance. The organisation also seeks to contribute to mutual trust and understanding among the member countries.[4] Other objectives include strengthening cooperation with other developing countries, and cooperating with international and regional organisations with similar aims and purposes.[5]

While SAARC has established itself as a regional forum, it has failed to attain its objectives. Numerous agreements have been signed and institutional mechanisms established under SAARC, but they have not been adequately implemented.[6] The South Asia Free Trade Agreement (SAFTA) is often highlighted as a prominent outcome of SAARC, but that, too, is yet to be implemented. Despite SAFTA coming into effect as early as 2006, the intra-regional trade continues to be at a meagre five percent.[7]

In the many failures of SAARC, lack of trust among the member countries has been the most significant factor between India and Pakistan. In recent times, Pakistan’s non-cooperation has stalled some major initiatives under SAARC.[8] For example, despite India’s keen interest in cooperating and strengthening intra-regional connectivity by backing the SAARC–MVA during the 18th summit of SAARC, the agreement was stalled following Pakistan’s reluctance. Similarly, the SAARC satellite project that India proposed was abandoned following objection from Pakistan in 2016.[9]

SAARC has also faced obstacles in the area of security cooperation. A major hindrance in this regard has been the lack of consensus on threat perceptions, since member countries disagree on the idea of threats.[10] For instance, while cross-border terrorism emanating from Pakistan is a major concern for India, Pakistan has failed to address these concerns.

Other significant reasons for SAARC’s failures include the following:

- The asymmetry between India and other member countries in terms of geography, economy, military strength and influence in the global arena make the smaller countries apprehensive. They perceive India as “Big Brother” and fear that it might use the SAARC to pursue hegemony in the region. The smaller neighbouring countries, therefore, have been reluctant to implement various agreements under SAARC.

- SAARC does not have any arrangement for resolving disputes or mediating conflicts. Disputes among the member countries often hamper consensus building, thus slowing down the decision-making process. SAARC’s inability in this regard has been detrimental to its growth.

- Given SAARC’s failures, member countries have turned to bilateralism, which in turn has adversely affected the organisation. Bilateralism is an easier option since it calls for dealings between only two countries, whereas SAARC—at a regional level—requires one country to deal with seven countries.[11] Thus, bilateralism decreases the countries’ dependence on SAARC to achieve their objectives, making them less interested in pursuing initiatives at a regional level.

- SAARC faces a shortage of resources, and countries have been reluctant to increase their contributions.

To make SAARC more effective, the organisation must be reformed and member countries must reach a consensus regarding the changes required. However, considering the differences that exist among the members, particularly between India and Pakistan, such a consensus will be difficult to reach. Until the member countries resolve their issues, the future of SAARC remains uncertain.

In recent years, BIMSTEC has gained popularity among South Asian countries as a platform for regional cooperation. It connects the littoral countries of the Bay of Bengal and the Himalayan ecologies. One of the reasons for BIMSTEC’s popularity is that the member countries have generally cordial relationships, something patently missing among the SAARC countries.

However, some observers of regional affairs in South Asia question the legitimacy of BIMSTEC as an alternative to SAARC.[12] Their scepticism arises from BIMSTEC’s less-than-impressive record in terms of tangible achievements, despite having existed since 1997.

The Need for Regional Cooperation

Before delving into the workings of BIMSTEC, one must understand the need for regional cooperation in South Asia in the first place. Trends in global affairs suggest growing resistance towards regional cooperation, once considered a preferred means for propelling economic prosperity among participating countries. Events such as the Brexit[13] and the US’ scrapping of the Trans-Pacific Partnership in 2017[14] reflect the global mood. However, contrary to global patterns, South Asian countries have shown an increased interest in regional cooperation. Setting up of the BBIN (Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal) subregional cooperation in the aftermath of the Kathmandu Summit of 2014 is a case in point.[15]

The South Asian region covers roughly three percent of the world’s total land area and is home to around 21 percent of the population.[16] The region has a diverse socioeconomic setup, including major economic powers such as India as well as a large number of poor people who live on less than a dollar per day. It also has a large young demographic, in search of employment.

South Asia is spread over a large land area between the mighty Himalayas in the north and Indian Ocean in the south. Among the countries in the region, only the island nations of Sri Lanka and Maldives are separated by waters; the rest are connected by land. Before 1947, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh were one integral nation, and the countries in the region have close sociocultural linguistic linkages. The countries, therefore, are closely tied in their sociopolitical state as they face similar threats and challenges. For example, most of the countries in the region have to deal with terrorism. To face such challenges, the South Asian countries must cooperate. The European and ASEAN experience is testimony to the contribution of regional cooperation in the economic growth of the countries.

BIMSTEC as Vehicle for Regional Cooperation

BIMSTEC includes the countries of the Bay of Bengal region: five countries from South Asia and two from ASEAN. The organisation is a bridge between South Asia and South East Asia. It includes all the major countries of South Asia, except Maldives, Afghanistan and Pakistan. Given this composition, BIMSTEC has emerged as a natural platform to test regional cooperation in the South Asian region.

Originally, BIMSTEC was called BIST-EC, i.e., Bangladesh, India, Sri Lanka and Thailand Economic Cooperation.[17] When Myanmar joined the cooperation, the organisation was renamed Bangladesh, India, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Thailand Economic Cooperation (BIMST-EC).[18] Following the inclusion of Nepal and Bhutan, the organisation was named BIMSTEC, i.e. Bangladesh, India, Sri Lanka and Thailand Economic Cooperation.[19]

BIMSTEC’s primary focus is on economic and technical cooperation among the countries of South Asia and South East Asia. So far, 14 sectors have been identified for enhancing regional cooperation among the member countries. Each sector has a lead country responsible for it. Table 1 lists the sectors and the lead country for each.

Table 1: BIMSTEC Sectors and Lead Countries

| Sectors |

Lead Countries |

|

1. Trade and Investment/Sub-sector

2. Technology/Sub-sector

3. Energy/Sub-sector

4. Transportation & Communication/Sub-sector

5. Tourism/Sub-sector

6. Fisheries/Sub-sector

7. Agriculture/Sub-sector

8. Cultural Cooperation/Sub-sector

9. Environment and Disaster Management/Sub-sector

10. Public Health/Sub-sector

11. People-to-People Contact/Sub-sector

12. Poverty Alleviation/Sub-sector

13. Counter-Terrorism and Transnational Crime/Sub-sector

14. Climate Change

|

Bangladesh

Sri Lanka

Myanmar

India

India

Thailand

Myanmar

Bhutan

India

Thailand

Thailand

Nepal

India

Bangladesh

|

Source: BIMSTEC Mechanism, www.bimstec.org.

BIMSTEC’s major strength comes from the fact that it includes two influential regional powers: Thailand and India. This adds to the comfort of smaller neighbours by reducing the fear of dominance by one big power.

BIMSTEC emerged out of the necessities of the member countries. India was motivated to join BIMSTEC as it wanted to enhance its connectivity with ASEAN countries: a major component of its Look East Policy, now rechristened ‘Act East’ policy. For Thailand, BIMSTEC helps achieve the country’s Look West Policy. BIMSTEC also helps smaller countries such as Bangladesh, Nepal and Bhutan to develop connectivity with ASEAN countries, the hub of major economic activities globally.

As a trade bloc, BIMSTEC provides many opportunities. The region has countries with the fastest-growing economies in the world. The combined GDP in the region is around US$2 trillion and will likely grow further. Trade among the BIMSTEC member countries reached six percent in just a decade, while in SAARC, it has remained around five percent since its inception. Compared to SAARC, BIMSTEC has greater trade potential as well. Among the member countries, Myanmar’s intra-BIMSTEC trade is around 36.14 percent of its total trade. Nepal and Sri Lanka’s share of intra-regional trade is around 59.13 percent and 18.42 percent, respectively. For Bangladesh, the intra-BIMSTEC trade share is 11.55 percent, while for India and Thailand, it is around three percent.[20]

Table 2: Growth and Standards of Living in BIMSTEC (US$ and %)

|

GDP Growth (%) |

GDP (US$ billions) |

Per capita GDP (US$) |

| India |

7.6 |

2250.987 |

1718.687 |

| Bangladesh |

6.9 |

226.76 |

1403.086 |

| Bhutan |

6.028 |

2.085 |

2635.086 |

| Myanmar |

8.072 |

68.277 |

1306.649 |

| Thailand |

3.234 |

390.592 |

5662.305 |

| Sri Lanka |

5 |

82.239 |

3869.778 |

| Nepal |

0.561 |

21.154 |

733.665 |

Source: International Monetary Fund and Chandra Mohan, “BIMSTEC: An idea whose time has come?” ORF Special Report, 9 November 2016.

Despite the many successes of BIMSTEC, however, some concerns remain. One is the infrequency of the BIMSTEC summits, the highest decision-making body of the organisation. In its 20 years of existence, the BIMSTEC summit has taken place only thrice. The first BIMSTEC summit was in Bangkok, Thailand in 2004. The second and third summits were held in New Delhi, India in 2008 and Nay Pi Taw, Myanmar in 2014. The fourth BIMSTEC summit, which was supposed to be held in Nepal in 2017, has been postponed. This calls into question the seriousness of the member countries. Moreover, the delay in the adoption of the Free Trade Agreement (FTA), a framework that was agreed upon in 2004, fuels doubts about BIMSTEC’s efficacy.

A landmark achievement for BIMSTEC was the establishment of a permanent secretariat in Dhaka. However, the secretariat faces a severe resource crunch, both in terms of money and manpower, which has adversely affected its performance.[21]

Observers of BIMSTEC consider the lack of leadership as the major drawback. In the past few years, this concern has been addressed as India has shown increased interest in the grouping. India’s initiatives have resulted in some important developments, including the setting up of the BIMSTEC Energy Centre in Bengaluru and the BIMSTEC Business Council, a forum for business organisations to promote regional trade. Various committees have been formed to oversee developments in various sectors, e.g. the BIMSTEC Transport Connectivity Working Group, which held its inception meeting in Bangkok in 2016.[22] The meeting finalised the terms of reference for the group, reviewed the development of the projects, and identified priority projects for strengthening cooperation among member states. A meeting of the national security advisers of all the member countries was held in Delhi in March 2017.[23] In August 2017, foreign ministers of all the countries met in Kathmandu, a crucial milestone as it makes for the second-highest decision-making body under the BIMSTEC framework.

Table 3: Meetings of BIMSTEC Foreign Ministers

|

· 1st Ministerial Meeting: 6 June 1997, Bangkok, Thailand

· Special Ministerial Meeting: 22 December 1997, Bangkok, Thailand

· 2nd Ministerial Meeting: 19 December 1998, Dhaka, Bangladesh

· 3rd Ministerial Meeting: 6 July 2000, New Delhi, India

· 4th Ministerial Meeting: 21 December 2001, Yangon, Myanmar

· 5th Ministerial Meeting: 20 December 2002, Colombo, Sri Lanka

· 6th Ministerial Meeting: 8 February 2004, Phuket, Thailand

· 7th Ministerial Meeting: 30 July 2004, Bangkok, Thailand

· 8th Ministerial Meeting: 18–19 December 2005, Dhaka, Bangladesh

· 9th Ministerial Meeting: 9 August 2006, New Delhi, India

· 10th Ministerial Meeting: 29 August 2008, New Delhi, India

· 11th Ministerial Meeting: 12 November 2008, New Delhi, India

· 12th Ministerial Meeting: 11 December 2009, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar

· 13th Ministerial Meeting: 22 January 2011, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar

· 14th Ministerial Meeting: 3 March 2014, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar

· 15th Ministerial Meeting: 11 August 2017, Kathmandu, Nepal

|

Source: BIMSTEC Mechanism, www.bimstec.org.

The developments so far under BIMSTEC have been encouraging. To maintain the momentum and to strengthen BIMSTEC as a sustainable platform for regional cooperation, the following steps must be considered:

- Consistency in the frequency of the summits to ensure regularity in decision-making;

- Improving the capacity of the secretariat, both in terms of manpower and funding;

- Ensuring tangible results/benefits, which will add to the motivation of the countries to concentrate on BIMSTEC (projects in the areas of tourism, digital connectivity, energy connectivity and humanitarian assistance in disaster relief should be considered); and

- Empowering BIMSTEC to be a platform for dispute resolution among member countries.[24] This will require debates and discussions among the BIMSTEC countries to reach consensus.

BIMSTEC offers many opportunities to its member countries. For India, it aids in its Look East Policy and South–South cooperation efforts. The development of the Northeastern region, by opening up to Bangladesh and Myanmar, is another incentive. For Thailand, BIMSTEC helps in its Look West policy. Under the BIMSTEC framework, smaller nations, too, can benefit from the markets in India and Thailand.

BIMSTEC provides the Bay of Bengal nations an opportunity to work together to create a common space for peace and development. Given the fairly amicable relationship among member states of BIMSTEC, implementing the suggestions listed above to increase BIMSTEC’s performance is an achievable goal as long as the countries exhibit enough political will and mutual respect.

Conclusion

The two organisations—SAARC and BIMSTEC—focus on geographically overlapping regions. However, this does not make them equal alternatives. SAARC is a purely regional organisation, whereas BIMSTEC is interregional and connects both South Asia and ASEAN. Insofar as their regions of interest overlap, SAARC and BIMSTEC complement each other in terms of functions and goals. BIMSTEC provides SAARC countries a unique opportunity to connect with ASEAN. Since the SAARC summit has only been postponed, not cancelled, the possibility of revival remains. The success of BIMSTEC does not render SAARC pointless; it only adds a new chapter in regional cooperation in South Asia.

ANNEXURE

- BIMSTEC vs SAARC: At a Glance

|

SAARC

|

BIMSTEC

|

|

1. A regional organisation looking into South Asia

2. Established in 1985; a product of the Cold War era

3. Member countries suffer for mistrust and suspicion

4. Suffers from regional politics

5. Asymmetric power balance

6. Intra-regional trade only 5 percent

|

1. Interregional organisation connecting South Asia and South East Asia.

2. Established in 1997 in the post-Cold War.

3. Members maintain reasonably friendly relations

4. Core objective is the improvement of economic cooperation among countries

5. Balancing of power with the presence of Thailand and India on the bloc

6. Intra-regional trade has increased around 6 percent in a decade

|

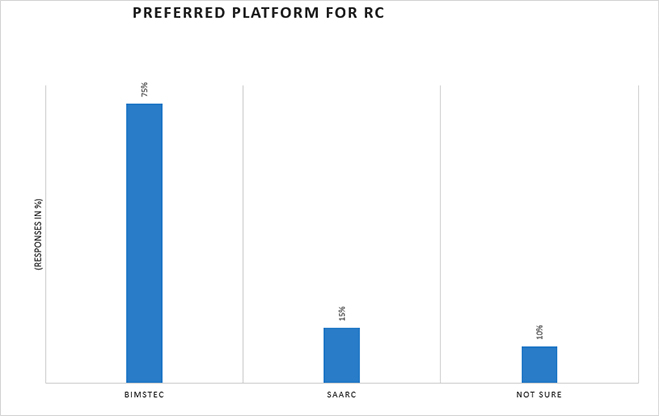

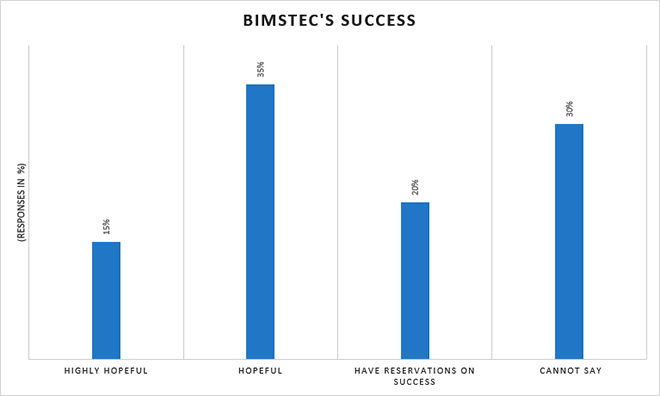

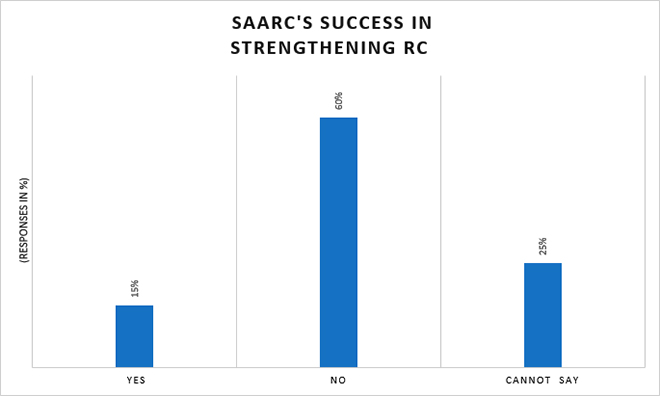

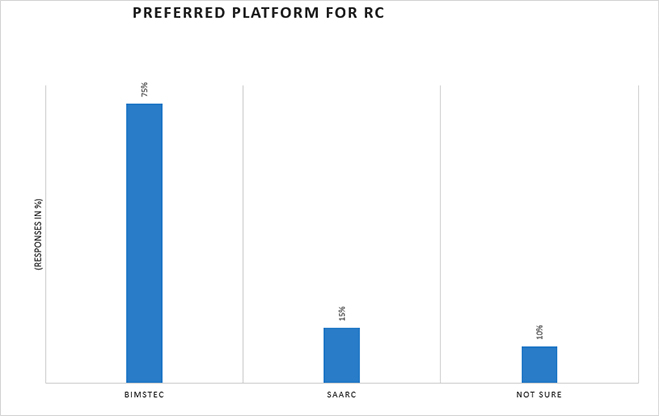

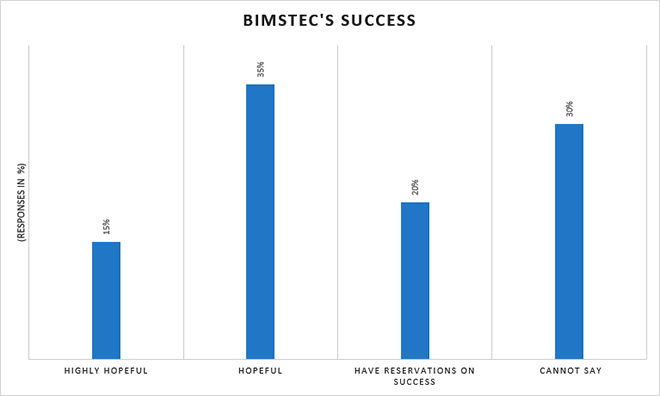

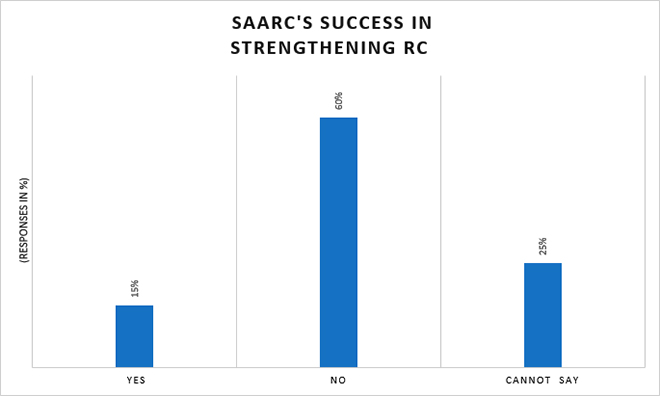

- BIMSTEC vs SAARC: Perception Survey of Stakeholders

The author conducted a brief perception survey of the stakeholders on the theme of the paper: BIMSTEC versus SAARC. Twenty stakeholders were interviewed—academics, former diplomats, journalists—as part of the survey. The respondents are from India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan and Sri Lanka.

The survey outcome is given below:

- What is your preferred platform for regional cooperation (RC): SAARC or BIMSTEC?

a) BIMSTEC: 15 stakeholders; 75 percent

b) SAARC: 3 stakeholders; 15 percent

c) Not Sure: 2 stakeholders; 10 percent

- What are your views on the potential success of BIMSTEC?

a) Highly hopeful: 3 stakeholders; 15 percent

b) Hopeful: 7 stakeholders; 35 percent

c) Have reservations: 4 stakeholders; 20 percent

d) Cannot say: 6 stakeholders; 30 percent

- Has SAARC been successful in strengthening RC?

a) Yes: 3 stakeholders; 15 percent

b) No: 12 stakeholders; 60 percent

c) Cannot say: 5 stakeholders; 25 percent

Endnotes

[1] Padmaja Murthy, “Relevance of SAARC” IDSA-india.in, accessed 18 October 2017.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Manzoor Ahmed, “SAARC Summit 1985-2016: The Cancellation Phenomenon,” IPRI Journal XVII (Winter 2017): 43–71.

[4] Article 1 Objective d: “…to contribute to mutual trust, understanding and appreciation of one another’s problems,” Charter of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation.

[5] Charter of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation, http://www.saarc-sec.org/SAARC-Charter/5/, accessed 19 October 2017.

[6] Major agreements and conventions under SAARC:

- Agreement on Avoidance of Double Taxation and Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters

- Agreement on Establishing the SAARC Seed Bank

- SAARC Convention on Narcotic Rugs and Psychotropic Substances

- Declaration on the Admission of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan into SAARC

- SAARC Agreement on Rapid Response to Natural Disasters

- Agreement on SAARC Preferential Trading Arrangement (SAPTA)

- Agreement on Establishing the SAARC Food Bank

- Agreement on Implementation of Regional Standards

- SAARC Convention on Regional Arrangements for the Promotion of Child Welfare in South Asia

- Agreement for Establishment of South Asian University

- SAARC Convention on Preventing and Combating Trafficking In Women and Children for Prostitution

- SAARC Convention on Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters

- SAARC Social Charter

- Protocol of Accession of Islamic Republic of Afghanistan to SAFTA

- SAARC Plan of Action on Poverty Alleviation

- Charter of the SAARC Development Fund

- SAARC CHARTER and Provisional Rules of Procedure

- Additional Protocol to the SAARC Regional Convention on Suppression of Terrorism

- Agreement on the Establishment of South Asian Regional Standards Organisation

- Memorandum of Understanding on the Establishment of the Secretariat

- Agreement on South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA)

- SAARC Convention on Cooperation on Environment

- Agreement on Establishing the SAARC Food Security Reserve

- SAARC Agreement on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Customs Matters

- SAARC Agreement on Trade in Services

- SAARC Regional Convention on Suppression of Terrorism

- Agreement for Establishment of SAARC Arbitration Council

- SAARC Agreement on Multilateral Arrangement on Recognition of Conformity Assessment

Digital Library, SAARC, http://saarc-sec.org/digital_library.

[7] “The Potential of Intra-regional Trade for South Asia,” The World Bank, 24 May 2016.

[8] Niharika Mandhana, “Is the India-Pakistan Rivalry Spoiling SAARC?” The World Street Journal, 26 November 2014.

[9] Jayanth Jacob, “How SAARC satellite project fell prey to India-Pakistan rivalry,” Hindustan Times, 23 March 2016.

[10] Zahid Shahab Ahmed, Regionalism and Regional Security in South Asia (London and New York: Routledge, 2016), 183.

[11] Raghav Thapar, “SAARC: Ineffective in Promoting Economic Cooperation in South Asia,” Stanford Journal of International Relations 7, no. 1 (Winter 2006).

[12] Views expressed by some foreign-policy analyst in Bangladesh and India on the efficacy of BIMSTEC as an alternative to SAARC during interviews with the author.

[13] The people of Britain voted for a British exit, or Brexit, from the EU in a historic referendum on 23 June 2016. “What is Brexit and what is going to happen now that Britain has voted to LEAVE the EU?” Daily Express, 5 November 2017.

[14] Peter Baker, “Trump Abandons Trans-Pacific Partnership, Obama’s Signature Trade Deal,” The New York, Times, 23 January 2017.

[15] Amit Kumar, “BBIN: Sub-Regionalism in the SAARC,” View Point Indian Council of World Affairs, 5 March 2015.

[16] Aparna Sharma and Chetna K. Rathore, “BIMSTEC and BCIM Initiatives and their Importance for India,” Discussion Paper, Cuts International, November 2015.

[17] BIMSTEC Overview, http://bimstec.org, accessed 7 November 2017.

[18] Myanmar was included on 22 December 1997, during a special Ministerial Meeting in Bangkok; Ibid.

[19] Nepal and Bhutan were admitted at the 6th Ministerial Meeting in February 2004, Thailand; Ibid.

[20] Ram Kumar Jha and Saurabh Kumar, “BIMSTEC abetter regional cooperation option than SAARC?” South Asia Monitor, 13 January 2015.

[21] Views expressed by speakers in a conference on BIMSTEC at ORF, New Delhi on 6 December 2017.

[22] MEA Annual Report, 2016–17, Government of India.

[23] First meeting of the BIMSTEC National Security Chiefs, Ministry of External Affairs Press Release, 21 March 2017.

[24] During the author’s interview with a few foreign-policy analysts—both in India and in Bangladesh—it was suggested that to strengthen the cooperation further, there is a need for preparedness to deal with disputes among the member countries. For instance, the exodus of Rohingyas from Myanmar to Bangladesh led to conflict between the two countries. The organisation must to equip itself to deal with such situations.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV