-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Om Bhandari, “Safeguarding Food Self-Sufficiency in the Time of COVID-19: Lessons from Bhutan,” ORF Issue Brief No. 429, December 2020, Observer Research Foundation.

Introduction

Global trade was already facing disruptions before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, owing to weakened growth and heightened US-China tensions; agriculture commodities were being disproportionately affected.i Consequently, the provision of adequate food and the prevention and management of COVID-19 have become priorities for countries battling the pandemic; this is true as well for the countries of BIMSTEC, or the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation. This forced a rebalancing of agribusiness activities, and the new agriculture and food value chains that have emerged will likely remain in place as the pandemic recedes. As countries became wary of exporting food items, the market has had little choice but to adapt by substituting, complementing and replacing products, and increasing prices.

Bhutan has a population of about 750,000 (two-thirds of whom live in rural areas), a growth rate of 1.2 percent, and a per capita income of US$3,423 (nominal).iiTo a notable extent, the country has succeeded in eliminating abject poverty.iii The overall unemployment rate of 3.1 percent fails to capture the challenge that among college-educated youth, prior to COVID-19, joblessness was at a high 67 percent.iv This figure could likely have only risen amidst the pandemic.

Although 98 percent of Bhutanese households are food-secure, 88 percent of children between six to 23 months are not being given the minimum acceptable diet.v Given that there is no widespread hunger in Bhutan, the government can focus efforts on boosting nutrition. Improved nutrition, especially among children and the elderly, requires serious attention from policymakers. The country’s experience in the food and agriculture sector during COVID-19 provides some insights on how this can be achieved.

Box 1: Agriculture in Bhutan

|

Productivity Bhutan’s economy is dependent on the agriculture, livestock and forest sectors, which provide livelihoods for about 57 percent of the population.vi The contribution of these sectors to the GDP has been increasing in absolute terms year-on-year but the overall contribution has been declining, from 45.1 percent in 1981 to 13 percent in 2017.vii |

Adaptation Farmers face various challenges, such as shortage of irrigation water, lack of agricultural workers, marginal land holdings, high transportation costs for inputs and marketing, and remote and scattered location of rural households. The impact of climate change has manifested in the form of floods, windstorms, erratic rainfall, new pests and diseases, increasing human-wildlife conflicts, and higher incidence of forest fires. |

|

Institutions Subsistence farming is an integral part of the Bhutanese economy, though efforts and programmes targeted towards semi-commercialisation are undertaken through farmers’ groups and primary cooperatives development. Farming is mostly at a small scale and dominated by rain-fed dry land and wetland farming. It depends on the monsoon rain, which accounts for 60 to 90 percent of annual precipitation. An additional activity for farmers is livestock rearing. |

Mitigation Recognising the potential impacts of climate change on agriculture, the government has encouraged Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA) to achieve food security under a changing climate and increased demand. However, farmers’ awareness of CSA and the associated opportunities and challenges is weak; the availability of CSA technologies is limited; and farmers do not have safety nets or alternative sources of livelihoods if investment activities fail. |

Source: World Bank, Climate Smart Agriculture Country Profile – Bhutanviii

LESSONS FROM BHUTAN

Bhutan has several entry points with India at border towns in West Bengal and Assam. Cordial bilateral ties and access to these markets have allowed the development of value chains in Bhutan’s fertile southern plains, far different from those in the mountainous interior and remote parts of the country. Essentially, one-third of Bhutan’s population have had easier access to a greater variety of food and vegetables at reasonable prices. Some interior regions of Bhutan have been dependent on India for food that have longer shelf lives, even though they could be grown within Bhutan.

As the COVID-19 pandemic spread rapidly, the import and export of food items was interrupted, and the availability of commodities disrupted due to higher transport costs, hoarding, inflationix and, in some cases, disposal of food along different parts of the supply chain.x Many parts of the food supply chains shifted entirely while others were shortened. Nevertheless, this provided an opportunity to rebalance and meet local needs through local production. The government, with assistance from development partners, has made efforts towards (i) achieving greater food self-sufficiency;xi (ii) improving logistical efficiency,xii partly aided by digital technology, which was not widely used in food supply chains prior to the pandemic;xiii (iii) import substitution;xiv and (iv) engaging qualified people in agriculture and food chains.xv The pandemic has encouraged Bhutan to import only those food items that cannot be produced or substituted internally.

BIMSTEC, of which Bhutan is a member, has regarded issues of food self-sufficiency and efficiency of food supply chains as among its priority agenda for several years. Following Bhutan’s lead, the other member countries can also look to replace food imports with local products, or procure these from their nearest BIMSTEC neighbour. Typically, the trade of agricultural produce does not fully account for impacts on self-sufficiency in the exporter country and hard currency needs of the importer nation, nor does it leverage e-technologies. This appears to be changing.

An important aspect in changing food supply chains in the BIMSTEC countries is the significant movement of people from urban to rural areas, and there is unlikely to be a rapid return of migrant workers. The impact of the May 2020 Amphan cyclone and the locust infestation in some BIMSTEC countries have also tested the resilience of the food supply chains.

Similar shifts may be seen in the supply chain of other sectors if the pandemic does not recede in the near future, but the change may not be as pronounced as in the food supply chain because they may be less critical or have a longer shelf life.

Between August and September 2020, Bhutan imposed a nearly month-long countrywide lockdown to reduce the spread of COVID-19 by restricting the movement of people. During this time, citizens were provided with one gigabyte of data free of charge to be able to use online services for the delivery of essential items.xvi Retailers allowed to operate were also able to connect with producers, other wholesalers and transporters to continue the supply of goods. Social media was used so that confined local zones could share information on infections and in contact tracing.

Even after the lockdown ended, the communication channels remained, aiding the reduced movement of people. Retailers were able to procure food items that people needed, even if they did not usually sell these products. At the same time, there was available information on products and goods that were being sold at the nearby stores, and they could be ordered online. This shows that improved access to information and technology in times of crises can boost access to food.

As food supply chains shift from being driven by demand instead of supply, Bhutan has initiated an exercise to map the sources of food to the nearest consumption centrexvii in a bid to encourage a quicker normalisation of food flow. This will also highlight the sector’s infrastructure needs, such as cold storage and warehousing, and may improve the efficiency of agricultural land use. But the country must also ensure nutrition and food diversity are considered.

Consumer demands can drive innovation aided by digital platforms. For instance, in the future, the consumer may want access to the fields where food is grown to monitor the progress. In Bhutan, as in other countries, people began to experiment in growing their own food. To serve this trend, the agricultural ministry launched the e-RNR Crop Advisory app, which currently hosts information on four crops (tomato, chilli, cabbage and cauliflower), from nursery management to harvesting.xviii

Access to safe and sustainable produce will be a focus as the BIMSTEC countries develop. But all member countries must be willing to achieve this goal. Collaboration and data sharing is of paramount importance. This will encourage diversification in agribusiness at the producer level, and help farmers, middlemen and businesses build resilience against future shocks. Bhutan is considering allowing private investments in state-owned agribusiness entities to improve efficiency especially in the agriculture sector.xix

At the same time, the push to use e-technologies and demand-driven food supply has given rise to several issues in Bhutan. First, rising prices and declining purchasing power has resulted in people consuming less nutritious food. This, in turn, has translated to increased malnutrition amongst children. School feeding programmes in remote areas provide nutritious and fortified food, which poor families may not be able to afford. Second, food handlers—transporters, traders, machine repairers, maintenance service providers and mobile food vendors—are more exposed to COVID-19 given the interactions with more people. Third, organic farming and the promotion of high-value crops have been deprioritised. Markets for such food items have been disrupted due to the breakdown in logistics and as the middle class’s reduced inclination to spend on such products. Finally, there has been an increased use of plastic bags as part of safety efforts in handling food and vegetables during the pandemic.

In the past, Bhutan has seen instances where formal food trade arrangements needed updating. For instances, it was found that potatoes were not on the export list submitted by Bhutan. As a result, the export of potatoes from Bhutan came to an abrupt halt as India increased vigilance and inspection of goods moving across the border due to COVID-19. Bhutanese farmers sought the government’s intervention to export a larger harvest of potatoes, resulting in some delays as authorities worked to resolve the bureaucratic obstacle.xx

The “mal” in “malnutrition” also refers to overnutrition. Indeed, Bhutan is seeing a growing burden of non-communicable diseases related to overnutrition. The Bhutanese consume rice in all meals, and there was rush to stock up on the grain when the pandemic hit. Bhutan imports half of its annual rice requirements.xxi Nutritionally, this consumption is not healthy, and is a contributing factor to the rising incidence of diabetes in the country.xxii

Box 2: Overview of Bhutan’s food and nutrition situation

The lack of data on food and nutrition in Bhutan makes it difficult to offer a comprehensive overview of the national situation. Nevertheless, it is established that Bhutan experiences a malnutrition burden among its under-five population. The national prevalence of under-five stunting is 21 percent, and the prevalence of under-five wasting is 4 percent. In children aged six to 59 months, over 44 percent were found to be anaemic, as were 35.6 percent of women of reproductive age.

Almost 40 percent of the Bhutanese population has at least one non-communicable disease (NCD), such as hypertension, diabetes, high cholesterol, alcohol-liver disease or tobacco-related diseases. NCDs are a major public health concern accounting for an estimated 62 percent of the country’s disease burden. According to health officials, deaths from NCDs increased from 53 percent in 2011 to 69 percent in 2018. Among them, 53 percent died before 70 years.

Sources: South Asia Monitor (2020)xxiii, Ministry of Health (2015)xxiv

Led by Prime Minister Lotay Tshering, a medical doctor, the government launched a campaign—Healthy DrukYul (healthy Bhutan)—to encourage a change in food habits from the traditional food of largely fat, salt and carbohydrates to a more vegetable and fibre-based diet. Physical exercise was encouraged; for three hours each day during the lockdown, people were allowed to step outside their homes in the locality. The campaign has emphasised the importance of better nutrition in fighting COVID-19 and other diseases. It also encouraged people to start kitchen gardens and buy local food items, avoid food waste, and share with those who cannot afford it.

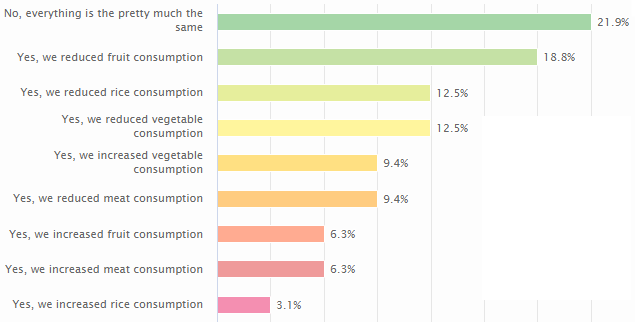

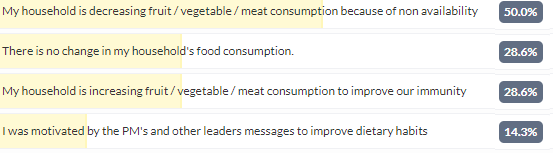

Given rising prices and non-availability of vegetables and fruits, many Bhutanese could not adopt nutritious diets. Forty random respondents participated in a poll conducted by the author in mid-October 2020, seeking insights on altered food habits during the pandemic.1

Figure 1: Responses to the question: “Has there been a general change in food habits in your family since the pandemic?”

Figure 2: Responses to the question: “If there has been a change in food consumption, why did it happen?

Although studies say that changing diets can reverse the damage caused by the food system to human health and the environment,xxv bringing about this change is no easy task. For instance, Bhutan grows maize, wheat and quinoa but these grains are not part of the regular diet and concerted efforts must be made to drive their consumption. The Healthy DrukYul campaign suggests local vegetables be used as a substitute for rice. Avoiding a second serving of rice alone will save the country US$40 million or 2 percent of GDP.xxvi The increased consumption of vegetables will serve another purpose as well; during the pandemic, a substantial volume of cabbage meant for exports was left over, which could have been consumed by the Bhutanese.

The banks will find it hard to maintain open credit lines to all players in the food supply chain if the pandemic continues for long. Other sources of cash must be tapped. The National Cottage and Small Industry Development Bank launched an investment scheme for farmers and the youth, with a loan ceiling of approximately US$6,500, which farmers can pay back after their harvest.xxvii Under the scheme, the agricultural ministry will also provide technical assistance to farmers, if needed. In another plan, by using funds from the National Resilience Fund, a six-month interest waiver followed by a 50-percent interest waiver for a further six months until March 2021 has been provided.xxviii In addition, a deferment of most loans has worked out with financial institutions. These initiatives have helped maintain confidence in the Bhutanese economy. About 63 percent of the respondents to the author’s poll agreed that the provision of low-interest, collateral-free loans was a good measure to assist farmers even though such interventions may heavily distort the market.

Physical isolation, financial hardships and the fear of job loss has had wide impacts, especially on the youth. Bhutan—which in 2010 banned the sale of tobacco and its consumption in public, and only allowed the import of controlled amounts of tobacco products on payment of hefty taxes—lifted the ban due to the pandemic.xxix Despite the health risks posed by tobacco, the government recognised that the illegal trade of tobacco products posed a greater threat of increased COVID-19 infections, opting instead to control its sale through state-owned outlets. About 63 percent of the respondents to the author’s poll agreed that this measure was more helpful than harmful.

Many politicians tend to disguise weaknesses to maintain public confidence, but this can create more problems in the future. The Bhutanese government was quick to inform the public of systemic weaknesses, and delineate areas where the country erred in ensuring food security.xxx Bhutan’s food marketing and distribution network was ill-prepared to meet the challenges of the pandemic; its preservation and post-harvest management systems were weak, for instance. Nevertheless, the country encouraged preparations for the winter months, when local vegetable production is low. A contingency plan and standard operating procedures were prepared on “how to import and export local produces, ensure internal distribution and on what the [agricultural] Ministry should do and what local government should do”.xxxi

The government proactively tackled other issues as well after openly acknowledging them. It tasked Food Corporation Bhutan to import all produce and distribute these to private vendors to ensure a continuous supply of vegetables.xxxii At the same time, the Bhutan Agriculture and Food Regulatory Authority signed a memorandum of understanding with the Export Inspection Council of India to facilitate the import and ensure the safety of foods of animal origin. These steps have led to optimism among the Bhutanese; 88 percent of the respondents in the author’s survey viewed as positive the involvement in agriculture of those displaced from other sectors.

CONCLUSION

Bhutan has fared comparatively better than many other countries in tackling the COVID-19 pandemic. The government’s national resilience fund totalling over US$400 million have been beneficial,xxxiii financial support for farmers and producers was prioritised, and the consumer protection and other agencies actively controlled the prices of essential items to avoid a strain on the public.xxxiv There is general optimism that food supply will improve after the pandemic; 56 percent of respondents in the author’s poll were positive of a quick shift in food supply as a result of the pandemic, and 81 percent said that food quality and nutrition will improve as the pandemic ebbs.

Despite being a relatively small country, Bhutan’s experiences in ensuring food security during the pandemic has many lessons for other countries, especially its fellow BIMSTEC members. This perhaps starts with mobilising a fund and supporting areas that best address the most critical issues. In the case of Bhutan, it was to prevent widespread outbreak of the disease, followed by ensuring adequate health and food services. This was followed by helping maintain people’s livelihoods as best as possible. The benefits of the deferment of principal and interest payments, cascaded to common people such as tenants, suppliers and employees of private businesses. The Build Bhutan Project, for example, was quick to employ displaced workers, returned migrants and others to projects where labour was necessary, where expatriate workers left, and in agricultural activities. An impetus towards greater use of digital technologies and more commercialisation of agriculture could be effected. In the process, leaders communicated regularly, both internally and externally, which helped solicit cooperation from its citizens and development partners. Similar measures can be altered or scaled up to serve the interests of countries through focused leadership that encourages people to cooperate and support policy initiatives.

About the Author

Om Bhandari is Bhutan’s head of the International Finance Corporation, a member of the World Bank Group. He works to bring about private-sector solutions to developmental gaps.

Endnotes

i David Frabotta, “Bigger than COVID-19: Three things affecting global agriculture”, AgriBusiness Global, November 17, 2020, https://www.agribusinessglobal.com/markets/bigger-than-covid-19-three-things-affecting-global-agriculture/.

ii Statistical Yearbook of Bhutan 2020, National Statistics Bureau of Bhutan, October 2020, V, 351, http://www.nsb.gov.bt/publication/files/SYB2020.pdf.

iii Bhutan Multidimensional Poverty Index, 2017, National Statistics Bureau of Bhutan, 2017, IX.

iv Tshering Dorji, “Lack of quality jobs despite heavy investment in education, says World Bank”, Kuensel, February 18, 2019, https://kuenselonline.com/lack-of-quality-jobs-despite-heavy-investment-in-education-says-world-bank/.

v Sonam Pelden, “UN Family ‘scaling up’ on Nutrition”, UNICEF Bhutan, May 11, 2020, https://www.unicef.org/rosa/press-releases/un-family-scaling-nutrition.

vi CIAT, World Bank, “Climate-Smart Agriculture in Bhutan. CSA Country Profiles for Asia Series. International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT)”, The World Bank. Washington, D.C., 2017, https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/sites/default/files/2019-06/CSA-in-Bhutan.pdf.

vii Choki Wangmo, “Working in Agriculture is Being Poor: WB”, Kuensel, February 7, 2020, https://kuenselonline.com/working-in-agriculture-is-being-poor-wb/.

viii CIAT, World Bank, “Climate-Smart Agriculture in Bhutan. CSA Country Profiles for Asia Series.”

ix Abhinya Chetri, “OCP: 170 complaints recorded in three weeks”, TheBhutanese, March 28, 2020, https://thebhutanese.bt/ocp-170-complaints-recorded-in-3-weeks/.

x Phub Dem, “Rotting cabbage and troubled farmers; Heavy rains damage vegetables in Dagana” Kuensel, July 18, 2020, https://kuenselonline.com/rotting-cabbage-and-troubled-farmers/.

xi “State of the Nation, Fourth Session The Third Parliament of Bhutan”, Royal Government of Bhutan, December 12, 2020, https://www.nab.gov.bt/assets/uploads/images/news/2020/State_of_the_Nation_2020.pdf.

xii WFP Bhutan Country Brief. WFP, August 2020, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/WFP-0000119085.pdf.

xiii “E-RNR Crop Advisory: A one stop platform for farming”, Ministry of Agriculture and Forests, Royal Government of Bhutan, November 4, 2020, http://www.moaf.gov.bt/e-rnr-crop-advisory-a-one-stop-platform-for-farming/.

xiv Karma Yuden, “MoAF Minister says vegetable imports to be regulated for import substitution”, TheBhutanese, September 19, 2020, https://thebhutanese.bt/moaf-minister-says-vegetable-imports-to-be-regulated-for-import-substitution/.

xvTenzin Lhamo, “Agriculture-Among The Most Viable Alternative Livelihood Options Amidst Coronavirus”, Business Bhutan, May 28, 2020, https://www.businessbhutan.bt/2020/05/28/agriculture-among-the-most-viable-alternative-livelihood-options-amidst-coronavirus/.

xvi“One-time free data and talk time from BTL and Tashicell”, Bhutan Infocomm and Media Authority, August 17, 2020, https://www.bicma.gov.bt/bicmanew/?p=5167.

xvii Yangyel Lhaden, “Bringing the market closer to farmers”, Kuensel, June 22, 2020, https://kuenselonline.com/bringing-the-market-closer-to-farmers/.

xviii Ministry of Agriculture and Forests, Royal Government of Bhutan,“ E-RNR Crop Advisory: A one stop platform for farming”

xix Tenzin Lamsang, “MoEA recommends allowing Bhutanese to invest abroad and MoF recommends divesting 30% shares of SOEs to the public”, TheBhutanese, November 14, 2020, https://thebhutanese.bt/moea-recommends-allowing-bhutanese-to-invest-abroad-and-mof-recommends-divesting-30-shares-of-soes-to-the-the-public/.

xx. “Potato and four other cash crops listed in the export list”, Bhutan Broadcasting Service, October 17, 2020, http://www.bbs.bt/news/?p=137620.

xxi “Agricultural Trade in Bhutan: Patterns, trends, and economic impact”, Ministry of Agriculture and Forests, August 2010, http://ebrary.ifpri.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/129183/filename/129394.pdf.

xxiiSonam Pem, “STEPS survey finds close to 90% Bhutanese not consuming enough fruits and veggies”, Bhutan Broadcasting Service, October 19, 2020, http://www.bbs.bt/news/?p=137695.

xxiii “Challenges for Bhutan’s health services”, South Asia Monitor, June 12,2020, https://southasiamonitor.org/bhutan/challenges-bhutans-health-services.

xxiv “National Nutrition Survey (NNS)”, Department of Public Health, Ministry of Health, 2015, http://maternalnutritionsouthasia.com/wp-content/uploads/Bhutan-NNS-2015.pdf.

xxv Loken. B. et.al., “Bending the Curve: The Restorative Power of Planet-Based Diets”, World Wide Fund for Nature. WWF Gland, Switzerland, 2020, https://c402277.ssl.cf1.rackcdn.com/publications/1387/files/original/Bending_the_Curve__The_Restorative_Power_of_Planet-Based_Diets_FULL_REPORT_FINAL.pdf.pdf?1602178156.

xxvi. “Bhutan PM initiates Healthy Drukyul campaign”, South Asia Monitor, July 31, 2020, https://southasiamonitor.org/bhutan/bhutan-pm-initiates-healthy-drukyul-campaign.

xxvii Choki Wangmo, “Investment scheme to benefit farmers”, Kuensel, October 7, 2020, https://kuenselonline.com/investment-scheme-to-benefit-farmers/.

xxviii Royal Government ofBhutan, “State of the Nation, Fourth Session The Third Parliament of Bhutan.”

xxix Phuntsho Wangdi, Nidup Gyeltshen, “Bhutan lifts tobacco ban to block COVID spillover from India”, Nikkei Asia, August 25, 2020, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Bhutan-lifts-tobacco-ban-to-block-COVID-spillover-from-India.

xxxTshering Dhendup, “Govt. assures there will be no ban on import of vegetable and fruits”, Bhutan Broadcasting Corporation, March 28, 2020, http://www.bbs.bt/news/?p=130320 “Delivering the essentials”, TheBhutanese, August 15, 2020. https://thebhutanese.bt/delivering-the-essentials/.

xxxi Karma Yuden, “Very poor marketing, distribution and post harvest management: Agriculture Minister”, December 9, 2020, https://thebhutanese.bt/very-poor-marketing-distribution-and-post-harvest-management-agriculture-minister/.

xxxii Choki Wangmo, “Govt. stocking essential items to last six months”, Kuensel, April 25, 2020, https://kuenselonline.com/govt-stocking-essential-items-to-last-six-months/.

xxxiii Royal Government ofBhutan, “State of the Nation, Fourth Session The Third Parliament of Bhutan.”

xxxiv Abhinya Chetri, “OCP: 170 complaints recorded in three weeks.”

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Om Bhandari is Bhutans head of the International Finance Corporation a member of the World Bank Group. He works to bring about private-sector solutions to ...

Read More +