-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

PDF Download

PDF Download

Ovee Karwa, Rishab Jain, and Sahil Deo, “Mapping the Literature on Development Assistance in Health: A Bibliometric Analysis,” ORF Occasional Paper No. 434, April 2024, Observer Research Foundation.

Introduction

Economic development is closely associated with good health, well-being, and education. Various concepts and indices, such as multidimensional poverty and the human development index, have been formulated to encompass social, political, and economic metrics to measure poverty and well-being. A critical aspect of human development is health and well-being. Health systems worldwide are combating unique disease burdens as per their contexts. While lower-middle- and low-income countries have made significant strides in tackling communicable diseases and maternal and child mortality, some countries continue to face a dual burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases.

Governments, international agencies, philanthropies, and private enterprises fund specific countries and health focus areas for better global and regional public health outcomes. For instance, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) includes health as part of its official development assistance (ODA; government aid that is specifically targeted towards the economic development and the welfare of developing countries). ODA spans many development sectors and is channelled through branches of the United Nations and other multilateral institutions. Development assistance for health (DAH) focuses only on health and includes aid from governments, private organisations, and philanthropies such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF).

DAH has consistently increased over the last decade to help countries eradicate diseases and strengthen their health infrastructure. Donors can fund various state, civil society, and private initiatives in health globally, channelling this funding through the State or civil society organisations and institutions. Donor entities fund various focus areas, such as reproductive health, maternal and child health, non-communicable diseases, tuberculosis, malaria, HIV/AIDS, and disease eradication programmes. Global and national eradication plans for diseases such as leprosy and polio have also received funding and human resources from global civil society organisations, philanthropies, and governments. Health and medical research, administration, and governance are some other key areas of health assistance. In 2021, global DAH amounted to US$67 billion.[1]

DAH recipients are mainly low- and middle-income countries that often lack the resources to address ‘avoidable’ healthcare issues, such as combatting communicable diseases and strengthening health systems. Notably, in recent years, assistance has also been used to address the burden of non-communicable diseases and conditions endemic to high-income countries.

The substantial amount of funding directed towards health outcomes in recent decades has already had an impact—diseases such as polio and leprosy have been eradicated in many countries, and infant and maternal mortality has drastically reduced.[2],[3] However, there are also doubts about the efficacy of health aid funding and its political rationales and social implications. Indeed, critiques of the medico-centricity of health aid,[a] and the scale of aid given against the recipients’ needs and governance constraints have highlighted the political nature of health assistance.[4]

Knowledge creation is an important aspect of this political nature. Concerns have been raised about diversity in the geography and country income levels of scientific publishing in various areas of public health.[5],[6] Understanding the production and dissemination of research casts light upon the subjects of research, the rationale for choosing these subjects, what is written about them, and who writes the research. It also shows whether the literature on health assistance is representative of the recipients on whom it has the most impact. Exploring author affiliations emphasises critical components of who is being spoken about and by whom. This holds significance in academia, mainly because newer research often builds on existing literature on the topic, and researchers play an important role in informing the larger discourse on donors and recipient countries and organisations.[7]

Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced the interconnectedness and impact of one country's governance on another. In the context of the coronavirus and among more long-term concerns such as antimicrobial resistance, countries appear to have realised that decision-making processes and public health governance in one country have the potential to affect other countries directly. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) echo this interconnectedness by encouraging all countries to implement policy interventions to achieve health and well-being targets.

This paper focuses on the politics of knowledge creation in development assistance to explore the representativeness of related literature. It seeks to guide future research priorities by answering the following questions:

As such, the areas explored are current trends and knowledge gaps in academic publications on development assistance and aid in health, the relation of research to global health aid funding, emerging areas in research, the role of philanthropies, and disparities in research output across countries, themes, and regions.

Methodology of Study

This paper uses both qualitative and quantitative methods to analyse bibliometric data on DAH. By analysing publication trends over time, policymakers can better understand the evolving landscape of research and innovation, enabling them to prioritise areas for policy intervention and investment. Indicators such as citation counts, h-index,[b] and journal impact[c] are employed to assess the influence of research outputs. With these, policymakers can evaluate the effectiveness of research funding programmes, measure the reach and dissemination of research findings, and identify high-impact publications and researchers.

Bibliometric analysis also allows policymakers to benchmark the research performance of institutions, regions, and countries against international standards. It promotes transparency and reproducibility in research by encouraging open science practices and data sharing. Policymakers can incentivise researchers to make their publications, datasets, and methodologies openly accessible, facilitating collaborative research, data reuse, and meta-analyses that can inform evidence-based policymaking and promote accountability and trust in the scientific enterprise. It can illuminate the disparities and inequities in research participation, representation, and impact across demographic groups, geographic regions, and research domains. Bibliometric indicators can be used to monitor inclusiveness in research, identify barriers to participation and advancement, and develop targeted interventions to support underrepresented researchers and enhance research equity and diversity.

For this research, various commonly used database repositories for bibliometric analysis, such as PubMed, Google Scholar, Dimensions, JSTOR, Scopus, and CrossRef, were used to consolidate literature on DAH between 2000 and 2022. PubMed was chosen for reasons elaborated upon in the following subsection. Thereafter, the following search filters were used across the titles and abstracts of papers in the database to choose the relevant ones: ‘foreign aid,’ ‘international aid,’ ‘development aid,’ ‘international assistance,’ and ‘development assistance and health’. The results were carefully parsed to eliminate false positives as far as possible.

Each paper was then divided into themes. Advanced search queries were developed at the final stage to segregate papers into relevant themes and regions of study. The World Bank database was used to conduct a region-of-study analysis based on the title and keywords of papers. A manual thematic analysis of all the papers was performed to avoid errors or exclusions.

Each author’s country of affiliation was categorised according to the World Bank’s classification of countries by income level. A section on the 50 most cited papers was added to understand funding for research.

The recommendations and conclusions of another subset of papers focused on health policy, international policy, and governance were also studied. These were similarly segregated into various thematic divisions to provide a snapshot of the major policy concerns and actions in DAH. The study followed the bibliometric analysis procedure laid out in How to Conduct a Bibliometric Analysis: An Overview and Guidelines (2021).[8]

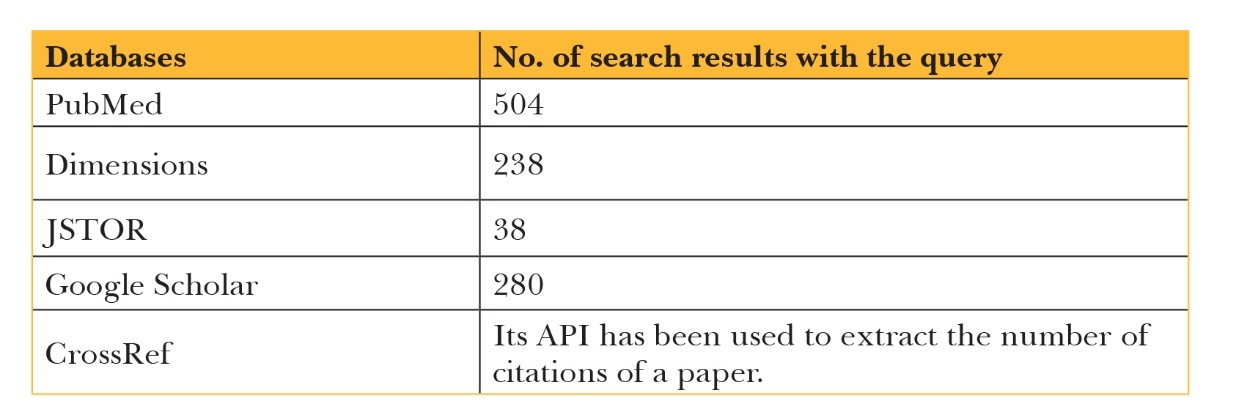

Researchers conducting bibliometric analyses use many databases, such as PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, Dimensions, JSTOR, and more. The choice usually depends on the area of analysis. Health and medicine-related research generally uses PubMed as it is a globally recognised and credible source. Even so, a preliminary overview of various databases was conducted to choose the one that would give the most relevant results. The findings were as follows:

Table 1: Databases and the Number of Search Results Based on the Same Query

Source: Authors’ own

Evidently, PubMed yielded the most results. In addition, the dataset obtained had the lowest rate of false positives, at around 3.1 percent. It also offered advanced search options where queries could be designed to yield the best dataset with minimal false positives so users could select the most relevant and accurate papers for their analysis, enhancing the quality of the results.

PubMed primarily focuses on biomedical literature, so it may not cover papers from other fields of study. This was combated by looking at Google Scholar and JSTOR as well, which yielded results from more social sciences and humanities-centric papers.

While PubMed does include papers in multiple languages, it is biased towards English-language publications. Non-English-language papers are commonly excluded from published systematic reviews. The high cost of professional translation services and associated time commitments are often cited as some of the barriers. This could limit the inclusivity of specific research conducted in non-English-speaking regions.

Each donor and recipient country could have more literature on the health focus areas and impact evaluation of funded projects, which may not be available on PubMed. This granular data is available on the official websites of government departments, philanthropic initiatives, NGOs, foundations, and bilateral and multilateral agencies. Since the research is limited to publicly accessible, global, health-related repositories available in English, the non-English-language data is excluded. As such, when it comes to thematic analysis of papers, some results, especially those in impact evaluation, may not represent the total literature in the field.

These were: "foreign aid" [Title/Abstract] OR "international aid" [Title/Abstract] OR "development aid" [Title/Abstract] OR "international assistance" [Title/Abstract] OR "development assistance" [Title/Abstract]) AND "health" [Title] AND “2000/01/01:2022/12/31” [Date - Publication].

From the final dataset of 504 data points, 15 duplicates were removed, leaving 489.

The DAH-Literature Paradox

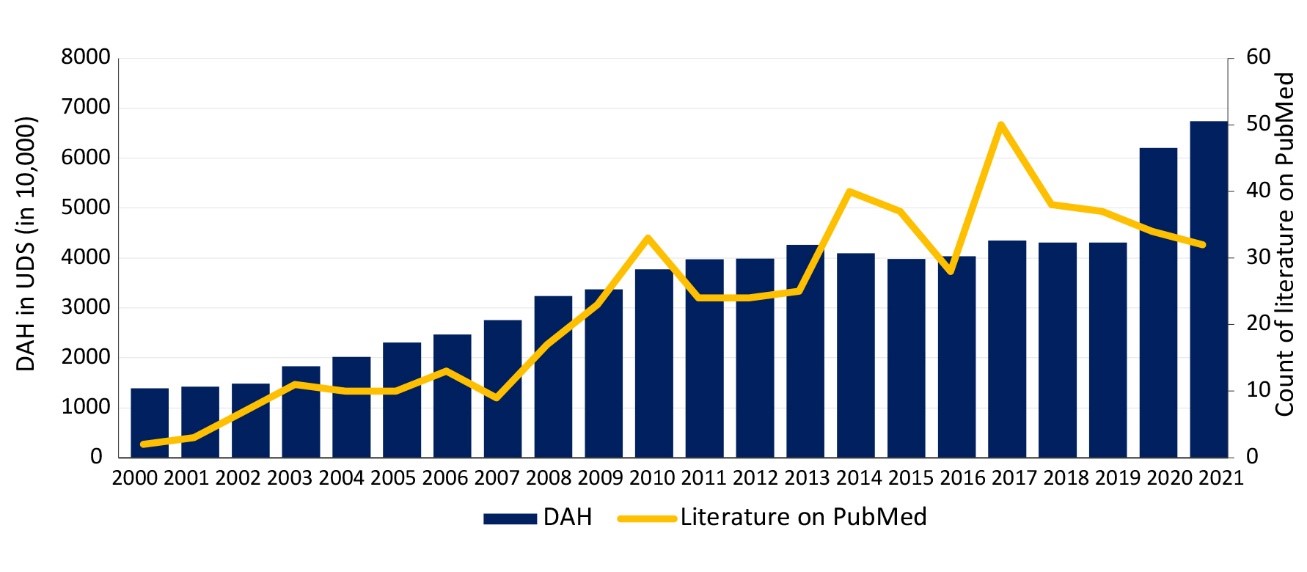

Of the 489 articles considered, 477 were in English, and the rest (12) were in Dutch, German, Japanese, Swedish, French, and Spanish. They include journal articles, historical articles, comparative studies, and media and news items. As can be seen in Figure 1, literature on both DAH and health aid (drawn from the prompt) saw a spurt from 2007. Annual health aid surged by over US$7 billion between 2007 and 2010, despite the 2008-09 global financial crisis.[9] One of the reasons for this increase was the higher returns and positive impacts that health funding had on welfare due to substantial improvements in health technologies during this period.[10] The spurt in the literature on health aid since 2007 could result from the gradual and consistent increase in DAH during that period. Another reason could be the growing recognition of global health as an area of study and the increasing emphasis on health equity and development goals since the 2000s.

Figure 1: DAH and Related Literature (2000-2021)

Source: Authors’ own, based on PubMed papers and IHME DAH (1990-2021)

However, after peaking in 2017, the volume of literature has steadily fallen, even though DAH remained constant for three years and has risen substantially since. This is surprising because research on health assistance should have spurted after 2018, given the COVID-19 pandemic and the large amounts of aid provided to address it globally. One possible reason could be that the pandemic shifted the focus towards understanding the immediate health and socioeconomic impacts of the virus and lockdowns. As a result, many researchers and institutions redirected their efforts and resources towards studying the novel coronavirus and its effects, leading to a relative decline in research output in many other health areas.

The literature drawn from PubMed was categorised under the following themes to understand current trends and knowledge gaps in academic publications on foreign health aid, as well as disparities in research output across countries, themes, and regions. Each paper was looked at for one to three of the following themes:

Funding pattern analysis (reveals which countries and entities get attention in the literature)

Health focus areas (reveal which papers explored the following diseases and other health areas, and compare it with the assistance received in those areas)

Commentaries on DAH (literature that assesses the impact of DAH on various health focus areas, countries, and regions, and that revolves around human rights and critical commentary on the politics of assistance)

In the literature on DAH, 81 of the 504 papers (or 16.5 percent) were about general funding trends. These papers sought to understand funding trends across specific time periods or in specific health focus areas. This research is helpful in understanding the changes in the flow of health assistance, the major stakeholders involved, and the channels of funding.

While some country-centric research on funding trends was also conducted, these have been considered in the following subsection.

Papers that focus on a specific country were divided into two groups: donors and recipients. The funding patterns and classifications of donors and recipients were derived from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) DAH database, and the World Bank country classifications by income level were used to categorise countries into low, lower-middle-, upper-middle-, and high-income countries. Country-specific research spans various themes: funding trends, health focus areas, political and human rights-based work, and policy recommendations.

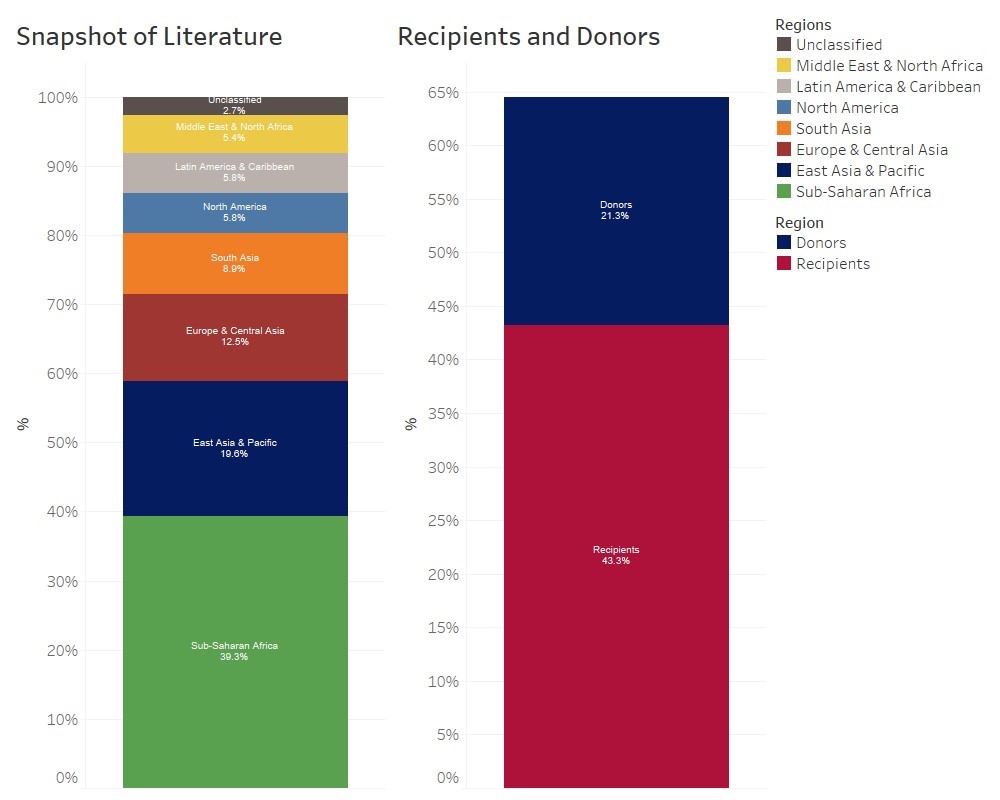

Figure 2: Snapshot of Literature on Regions of Study and Donors and Recipients

Source: Authors’ own, based on PubMed papers and IHME DAH (1990-2021)

About 43.3 percent of country-specific literature revolved around the recipients of DAH, mostly concentrating on their health systems and on the outcomes in health focus areas.

Research on assistance allocation has noted that disaster and conflict areas receive more DAH than others. This is especially true for certain types of assistance, such as humanitarian and mental health assistance.[11] Filtering for the words ‘emergency,’ ‘disaster,’ ‘conflict,’ ‘conflict-afflicted,’ ‘flood,’ ‘earthquake,’ ‘tsunami,’ and other natural disasters in the titles and keywords, it was found that 17 country-specific papers and two region-specific ones were about disasters and conflict areas. These constituted 13.9 percent of the recipient-centric papers, indicating that while disaster and conflict contexts do attract assistance in health, literature about these specific aspects does not constitute a large proportion of the literature on recipient countries.

Impact evaluation studies constituted 15.5 percent of the recipient-centric literature. This number is not representative of the volume of impact evaluation literature, which may be majorly housed with bilateral and multilateral agencies and the organisations that provide DAH.

Only 8.1 percent of the papers mentioned health policy, foreign policy, or governance among the recipient countries, and only two papers revolved around the fungibility of foreign aid and government expenditure in health.[d] This lack of focus on the intersection of health assistance and policy and governance is an important gap in the literature, considering the influence of donors and aid on health policy and existing research on the insufficient capacity of countries to absorb aid.[12],[13],[14]

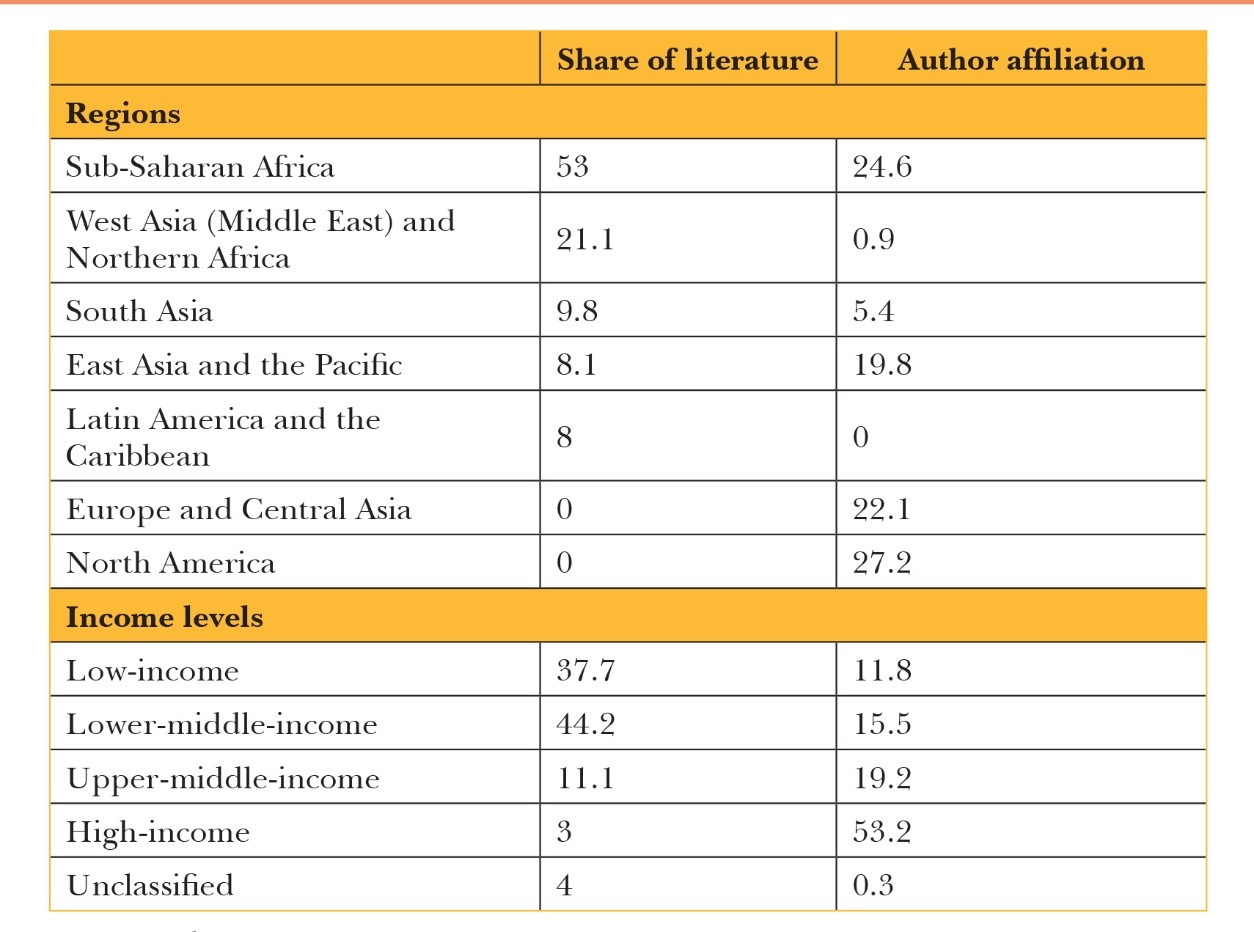

In terms of regions of study, more than half (53 percent) of the papers were about recipient countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, followed by South Asia (9.8 percent), and East Asia and the Pacific (8.1 percent). The focus in 44.2 percent of the papers was on lower-middle-income countries, followed by low-income countries, which constitute 37.7 percent of the recipient-centric literature.

Most of the recipient-centric literature focused on lower-middle and low-income countries. This has been juxtaposed with author affiliations by region and income levels, and the DAH received by the respective income categories and regions. Given that most of the papers in recipient-centric literature were about health systems and health focus areas, and some on health policy and governance, it is an important area to comment upon.

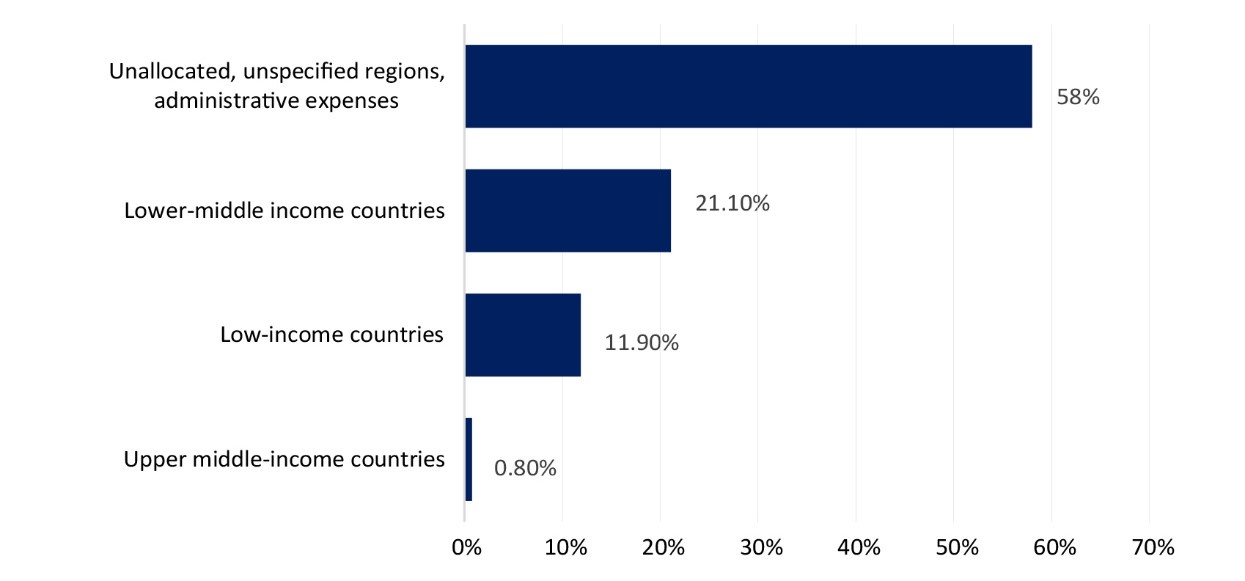

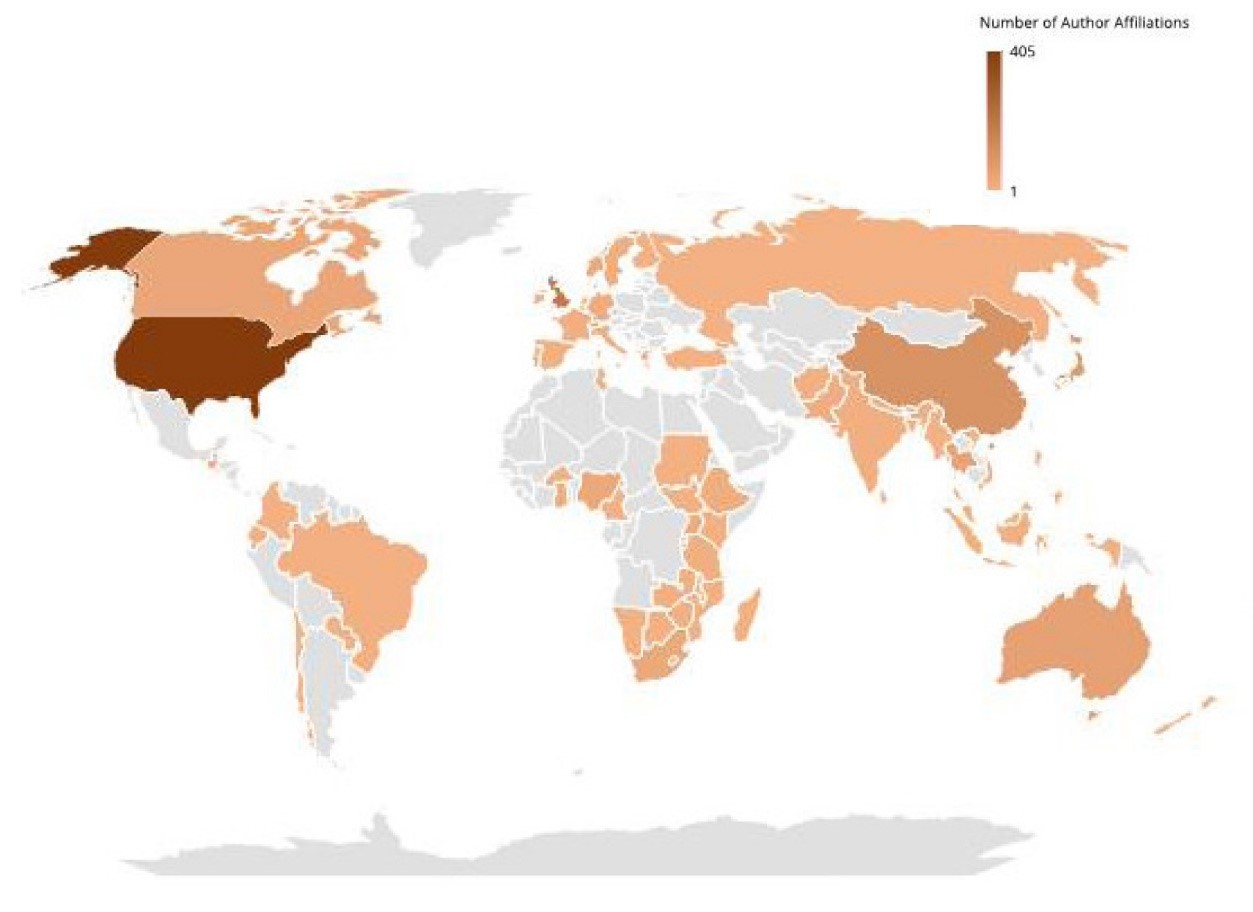

According to the IHME DAH (1990-2021) database, 58 percent of the total aid is spent on unallocated and unspecified regions and in administrative expenses. The rest goes majorly to lower-middle-income countries (21.1 percent), followed by low-income countries (11.9 percent), and upper-middle-income countries (0.8 percent). However, among the authors of literature on recipient countries, 53.2 percent came from high-income countries, followed by 19.2 percent from upper-middle-income countries. Authors affiliated with institutes and organisations from lower-middle- and low-income countries constituted merely 15.5 percent and 11.8 percent, respectively. Regionally, this distribution is as follows: 27.2 percent of the authors are affiliated with North America, 24.6 percent with Sub-Saharan Africa, 22.1 percent with Europe and Central Asia, 19.8 percent with East Asia and Pacific, and 0.1 percent with West Asia (Middle East) and Northern Africa. While the literature on South Asian countries constituted 9.8 percent of the recipient-centric literature, only 5.4 percent of the authors were affiliated with the region. There was no author from Latin America and the Caribbean, even though 8 percent of the literature was focused on the region.

Figure 3: Allocations of DAH (2000-2021)

Source: CPC Analytics, based on IHME DAH data

Figure 3 shows that, excluding the unallocated/unspecified and administrative expenses, the largest chunk of DAH has gone to lower-middle-income countries, followed by low-income countries. Most of the literature (see Table 2) is devoted to Sub-Saharan Africa (53 percent), West Asia (Middle East) and Northern Africa (21.1 percent), followed by South Asia (9.8 percent), and East Asia and the Pacific (8 percent). Authors affiliated with organisations and institutions predominantly in North America (27.2 percent), Sub-Saharan Africa (24.6 percent), Europe and Central Asia (22.1 percent), and East Asia and Pacific (19.8 percent) contributed to the literature. Notably, a minuscule percentage of authors (0.9 percent) were affiliated to the West Asia (Middle East) and Northern Africa region, and no author was affiliated to the Latin America and Caribbean region, despite it constituting 5 percent of the total DAH and 8 percent of the literature. While authors affiliated with Sub-Saharan Africa constituted about 25 percent of all the authors, a significant proportion of the literature about DAH was produced by authors affiliated with countries and regions that do not receive aid.

Table 2: Recipient-centric Research – Share of Literature and Author Affiliations (in %)

Source: Authors’ own

Of the country-specific literature, 33 percent focused on countries that are DAH donors. Articles examining countries such as China and India, which are both donors and recipients, were separated according to the context in which they were mentioned.

Most of the donor-country literature is about donors in East Asia and the Pacific (45 percent), followed by Europe and Central Asia (23.3 percent), and North America (20 percent). Further, it was found that 70 percent of the papers were about high-income donors and 23.3 percent about upper-middle-income donors. The most frequently discussed donors were China (23.3 percent of the total donor-centric literature), the US (15 percent), Japan (13.3 percent), and the UK (11.7 percent). Despite China contributing only 2.5 percent of the total DAH directly (from public sector funds and its national treasury), it gets significant attention in donor-centric research. Literature on China is focused on the rationale and politics of its aid towards African countries and its foreign policy.

Donor country-centric literature documents the trends of contribution, health focus areas of contribution, various perspectives of different stakeholders, and the associated sociopolitical and economic factors. Notably, few impact evaluation studies (8.3 percent) were found in donor-specific literature. Similarly, only two studies have explicitly focused on health or foreign policy, highlighting the gap in literature yet again.

Private organisations and foundations are some of the top DAH donors (constituting 18.8 percent of the total donorship in DAH between 2000 and 2021). Private donors have robust output- and impact-driven funding rationales, with some global foundations providing project-wise details of funding and impact on their websites. However, the literature focused on the role and contribution of private funders and NGOs, philanthropies, and foundations in DAH is scant. Most of what is available measures the funding patterns of these entities, with few impact evaluation studies and social commentaries on the politics of aid. The World Bank, BMGF, and other development bank-funded projects have their impact evaluation and project completion reports on their websites, but these are not a part of PubMed.

An in-depth analysis of papers thematically categorised under ‘NGO/Philanthropy’ was conducted to understand the academic literature in this area. Only 19 of them had the phrases ‘private businesses,’ ‘business(es),’ ‘civil society organisations,’ ‘philanthropies,’ ‘non-governmental organisations,’ ‘international NGOs,’ and ‘foundation’ in their titles or keywords. Some of the most used databases to understand private contributions are IHME DAH, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Global Health Expenditure Database, the WHO’s Global Health Observatory, the OECD Development Assessment Committee’s (DAC) reports, and the WHO’s National Health Accounts. Only three papers directly used the annual financial statements of the foundations they shortlisted.

Private and philanthropic donorship to countries, organisations and faith-based organisations is a nascent but important niche, given its steadily increasing contribution to DAH. Most of the academic research revolving around NGOs, philanthropies, and private businesses picked up only after 2017 and continues to be funded by one or two major funders, such as the BMGF or the US National Institute of Health (NIH). Most of the authors of these papers are associated with high-income countries. This again points to a large gap in the literature on health aid, with the point of view of low- and middle-income countries, the largest recipients of DAH, largely missing.

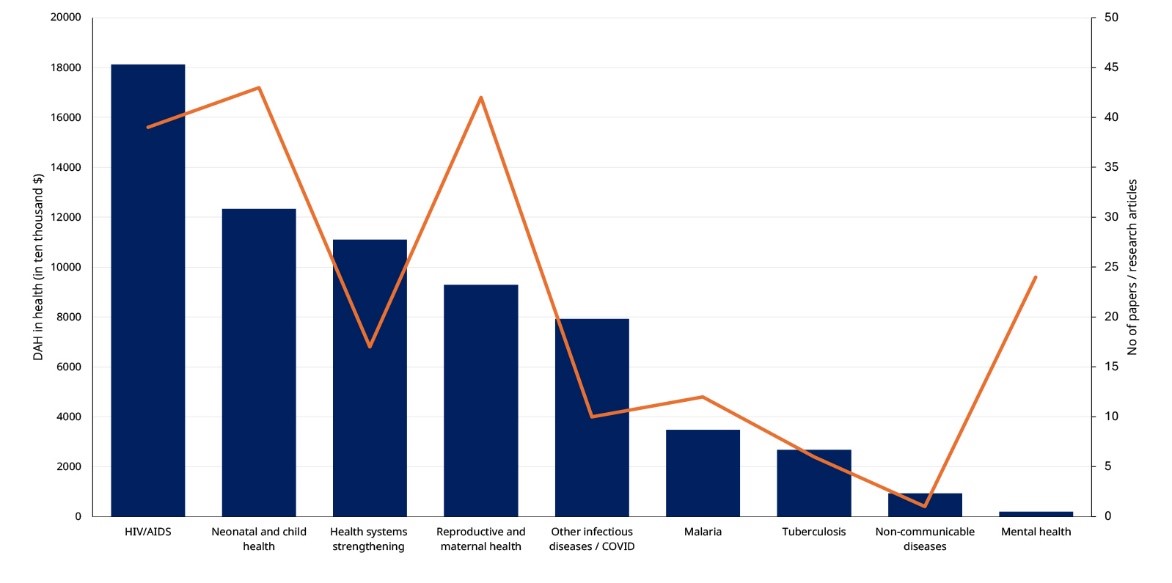

DAH is disbursed under various health focus areas, such as COVID-19 and other infectious diseases, non-communicable diseases, tuberculosis, and reproductive and maternal health. Figure 4 showcases the share of funding in these areas and the literature on them.

Figure 4: Funding in Health Focus Areas and Share of Literature (2000-2021)

Source: Authors’ own, based on PubMed papers and IHME DAH (1990-2021)

While the number of papers is small (the maximum is 43 for neonatal and child health), it helps understand the varying emphases on the different focuses of research. There is no correlation between the DAH for a particular health focus area and the literature on it. A large disparity is visible between the funding received and the focus of literature in mental health. There were only 24 papers found on the subject, while the DAH for mental health exceeded US$20 million over the period of study. More research is evidently needed to understand the impact of DAH in each of these focus areas.

Another important theme in the literature on health aid is the politics of assistance. While most papers comment on donor and recipient politics, or the rationale for funding, geopolitics, governance, and so on, some papers are devoted solely to these topics. To separate them, papers that had the words ‘advocacy,’ ‘human rights,’ ‘politics,’ ‘political economy,’ ‘power,’ ‘culture’ (and related words), ‘globalisation,’ ‘equity,’ ‘inequality,’ ‘ethics,’ ‘constitutionalism,’ and ‘neo-liberal’ in their titles, abstracts, or keywords were considered. A manual screening of all papers also helped identify those that included sociopolitical critiques but did not contain the words.

It was found that 9.6 percent of the papers have built a sociopolitical critique; 3 percent of them mentioned human rights (or health as a human right) along with advocacy in their titles; 2.2 percent built a critique on the rationale or politics of DAH funding; and 1.8 percent focused on universal health coverage. Overall, only 6.1 percent of the papers mentioned ‘health policy,’ ‘governance,’ or ‘foreign policy’ in their titles or keywords.

Most of the literature on sociopolitical analysis, the rationale for aid, and about human rights and advocacy came from authors affiliated with high-income countries (77.5 percent), followed by upper-middle-income countries (21 percent). The trends in terms of region were similar as well, with most authors affiliated with organisations or independent research from North America (30.4 percent), Europe and Central Asia (19.7 percent), and East Asia and the Pacific (18.1 percent).

A grant analysis for the top 50 cited papers in health aid was conducted by checking for funding information in PubMed and the official publishing site. Funding information for 25 of the 50 papers was available. Of these, 19 were funded by the BMGF, five by the NIH, and one by a philanthropic organisation. Only those funded by the BMGF had information on funding available for each paper.

Most authors were found to be affiliated with the US (30.6 percent) and the UK (14.9 percent), followed by China (7.5 percent), Japan (5.9 percent), and Australia (3.9 percent). Authors affiliated with institutions and organisations in high-income countries contributed 71.5 percent of the research, followed by upper-middle-income (15.7 percent), lower-middle-income (8.5 percent), and low-income countries (4.3 percent). This shows the stark difference in the site of the subject and production of knowledge.

Map 1: Author Affiliations by Countries

Source: CPC Analytics, based on PubMed data

Policy Recommendations

Papers relating to DAH often include policy recommendations for donors, recipients, and international aid organisations. These were extracted using the filters ‘health policy,’ ‘policy,’ ‘governance,’ ‘international relations,’ and ‘government’ in their abstracts, keywords, and main policy recommendations. These recommendations have been clubbed thematically:

One of the most frequent policy recommendations was the need to collect more evidence of and data on DAH fund flow.[15],[16],[17] Researchers noted that decision-makers were often confounded by the lack of reliable data mapping the flow of assistance and the key stakeholders involved. Data helps to assess whether assistance commitments are being followed through and provides evidence for or against the anecdotal claims of the negative effects of assistance.[18] Further, more data helps to set objective criteria in assessing and rewarding performance, which are currently lacking in sector-wise approaches. Structured and quantitative benchmarks are badly needed.[19] With a significant proportion of assistance being funded by philanthropies and private donors, and non-OECD countries, data tracking mechanisms, particularly for non-OECD and private donors, need improvement and integration into the common databases.[20]

The details of much of the funding through NGOs and international development institutions are often not available. There have been charges that some of this funding is a form of tax evasion, or legal but ethically questionable tax avoidance. Urging better financial disclosure can reduce such instances. Tax evasion can be ended by changing banking rules to prevent the transfer of wealth to opaque financial centres.[21] It has been suggested that even the WHO is not truly independent because of its dependence on extra-budgetary funding, and that there should be an independent institution or forum to monitor donors, either at the national and global level.[22]

Another issue raised by scholars is the lack of impact assessment mechanisms. Impact assessment studies are often conducted internally, and recipients are expected to comply with strict deliverables. Even so, lack of transparency and doubt about impact remains pervasive due to the lack of publicly available data. It has also been suggested that, for all assistance provided, there should be a rigorous cost-benefit analysis. Where such analysis is impossible, cost-effectiveness analysis should be done routinely, especially when evaluating interventions or service delivery changes.[23] Donors should provide financial and technical assistance to recipient countries to develop data tracking systems, facilitating effective coordination in budgeting and aid performance monitoring.[24]

DAH resource allocation often does not align with the recipient disease burdens.[25] It is also noted that allocations are more likely to be spent on combating immediate crises, and there is a need to refocus on longer-term sector-wide objectives instead of short-term programmes.[26]

Researchers have called for a wide range of metrics, including disease burden, to be used in allocation. Allocation frameworks should also consider national income, individual poverty, governance, and epidemiological surroundings for increased impact on health outcomes.[27] Notably, certain health behaviours and policy changes can reduce social inequality, but the wealthy tend to benefit more from health service provisions driven by DAH in some countries.[28] There are stark variations in countries getting assistance as well; for instance, the rapid expansion of health aid to control and prevent sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) in Africa has been accompanied by a stark imbalance in the volume of funds allocated to individual countries. Countries with a high burden of STDs but relatively low populations received less assistance compared to other countries.[29]

Lessons from a study in four developing countries (Bangladesh, Ecuador, Egypt, and Indonesia), where reductions in child mortality exceeded expectations given their economic circumstances, indicated that targeted health interventions, foreign aid, and technical assistance matter more than contextual factors such as economic development and governance in raising health standards. This contradicts the prevailing wisdom in mainstream literature on DAH that comprehensive health services need to be improved first for child mortality to be reduced.[30]

The primary recommendation to donors is that aid should be directed towards building capacities within recipient countries. Funnelling assistance through the government instead of NGOs is better. Conducting research itself has many positive outcomes, ranging from capacity-building for research to supporting local policymakers and enhancing the skills of healthcare professionals.[31],[32] To make donor aid effective, administrative costs should be regulated, outcome predictability should be improved, private sector capacity built further, and frameworks set up to measure additionality.[33]

Another recommendation is that developing economies should be granted greater trade treaty flexibilities until their domestic revenue sources allow for sustainable financing of public health, education, and social protection systems.[34] Short-term financing may create long-term financing gaps with consequential costs to public health systems. It is important to assess whether long-term gains offset financial costs imposed on broader public health systems.[35]

One study noted that development is achieved more efficiently if all aid is channelled through a single government department rather than split among several. Making a high-level functionary (preferably at the cabinet level) responsible—such as one that has leadership skills and a political profile and who engages with outside experts (including business interests)—will also help.[36] Another pointed out that, for instance, the US’s contribution to DAH in Sub-Saharan Africa was larger and better targeted than its non-health aid, and had resulted in improvements in state stability metrics across the region.[37] It was also suggested that donors should fund health innovation initiatives in the recipient countries, as locally relevant diagnostics, drugs, and devices present an opportunity to increase domestic capacity and a shift away from foreign aid dependency.[38]

One critical tip from the papers examined was that donors should continue health funding even if recipient organisations were to fail to deliver on targets because it was important to maintain long-term relationships based on trust and not undermine health sector performance by withdrawing aid.[39] It was also pointed out that properly targeted DAH helps to make groups and communities marginalised or overlooked in a country’s priorities more visible.[40],[41] However, in some cases, donor countries do not fund politically-contested health areas in their own jurisdictions. For instance, Norway has given little development support to the improvement of maternity services, avoided the issues of abortion and post-coital contraception, and passed up opportunities to support adolescent services. The revitalisation of the reproductive rights discourse in Norway could provide scope for policy discussions and decisions in relation to Norway’s development assistance.[42]

In recent years, DAH from new high-income countries, such as South Korea, and even developing countries, such as China, has increased steadily.[43] Several studies have discussed the reasons for this increase, while also identifying what the countries can do better. China, for instance, could enhance its donor status by participating more actively in the global health dialogue and carefully evaluating its health assistance investments.[44],[45] However, a challenge that new donors might face is in providing capacity-development services that require the donor to have a high level of capacity.[46]

Additionally, some donors find it especially difficult to continue working or adjust their existing mandates in regions that were previously peaceful but are now facing political unrest. To tackle this, some papers recommend that the donors’ representatives in countries should be granted more decision power to allow for more flexibility of funds in a coordinated way to alternative channels (for example, NGOs, local governments, district hospitals, and health centres). This can be especially useful when central government budget channels cannot be used.[47]

A major criticism of donor funding approaches is that they demand unsustainable quick-impact solutions to health system problems.[48] Often, assistance is given to countries through equipment and medication without a proper distribution infrastructure in place. A case study in Ukraine,[49] for instance, detailed the basic administrative considerations that any humanitarian organisation must consider before sending assistance, such as ensuring the recipient has the appropriate approvals and documentation to receive aid directly from the donor. Donors must ask for hospitals’ annual reports and other relevant documents, which provide a statistical summary of staffing levels, equipment usage, and patient types and would help better align donations. They should not assume that the hospital requires or can use all types of medical equipment and medical supplies. Relevant training must be provided, and locally manufactured equipment encouraged, ensuring that equipment servicing is not a burden. Donors should establish a follow-up protocol to ensure that donations reach their intended recipients.

In the late 2000s, there was a spurt in the literature about African countries grappling with a massive human resource crisis due to brain drain, especially of nurses, along with policy recommendations to prevent it. It was suggested that global health institutions should provide longer-term funding for additional human resources, ensuring sustainability and quality in the programmes they support. Retraining existing staff and long-term staff development were also integral components of this strategy.[50] Other strategies included improving the nursing educational system, providing financial assistance to student nurses, increasing enrolment in nursing schools, and advertising attractive recruitment packages for healthcare jobs.[51] It was also proposed that global health education initiatives should use blended learning models, especially in lower- and middle-income countries, to disseminate information on global health topics effectively.[52]

DAH has an important role in strengthening health systems in low-income countries.[53] In some impoverished African countries, for instance, foundational health programmes such as the provision of comprehensive community healthcare are not possible without foreign aid.[54] Additionally, external resource inflows targeting health have spurred economic progress in good policy environments in African countries, with some even consequently reducing their macroeconomic fiscal deficit in the 2000s.[55] Indeed, there is evidence that a greater emphasis on the health aid network leads to better child survival rates.[56],[57]

Government ministries in recipient countries play a pivotal role in setting health priorities; aid should align with these priorities while also contributing to capacity building. Several studies assessed in this report emphasised the importance of aid supporting the recipient country’s long-term objectives rather than dictating policies that may not align with local needs. One paper, for instance, underlined the importance of recipient countries understanding macroeconomic factors that may be beyond the control of a single ministry while planning DAH expenditure, such as the level of inflation and its impact, and the government’s (limited) ability to expand public spending, irrespective of aid availability.[58] At the same time, it noted there were also factors that were within the control of health authorities, such as the pace at which aid is spent and checking whether the spending exacerbates or mitigates local-capacity bottlenecks. It added that if aid relaxes bottlenecks (for instance, by training new health staff), its adverse macroeconomic effects are likely to be mitigated or even eliminated.[59]

The extent of a recipient country’s dependence on assistance also impacts the implementation of global health initiatives (GHIs).[e] For instance, in Angola, which is not entirely dependent on external funding, the national strategic programme is well-synchronised with GHI interventions, but this was not the case in Mozambique, which is heavily dependent on external aid.[60] In Ghana, the government responded to the proliferation of health-sector donors by promoting harmonisation and alignment. While this reduced the government’s transaction costs, it increased the donor’s coordination costs. Such harmonisation measures could prompt donors to revert to standalone projects for increased accountability, indicating the challenges of balancing coordination and flexibility.[61] In Uganda, on the other hand, the main hindrances to sound planning and implementation of DAH funded programmes were the country’s poor accountability framework, its ineffective supply chain of health commodities, its negative cultural beliefs, insufficient government funding for healthcare, insufficient alignment of development assistance with the National Development Plan, and non-compliance with the 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness.[f] Countering this requires a complete reassessment of the pharmaceutical chain to build a new framework of cooperation between the health and finance ministries, the district health teams, and the facilities available for effective distribution. The multiplicity of donor missions, the diverse set of policy settings, and inconsistent reporting that led to administrative resources being misused greatly increased the local district governments’ transaction costs, indicating a need for a template for coordination.[62]

Trust is also a crucial factor for the continued flow of DAH. Revelations of fraud, such as the 2013 Cashgate scandal in Malawi,[g] inevitably lead to mistrust among stakeholders, impacting the health system.[63],[64] Along with corruption, excessive government expenditure and poor governance indicators can also lead to donors withholding committed assistance.[65] One paper noted that low-income countries must coordinate among themselves through coalitions and global summits to better convey their requirements and strengthen best practices.[66]

Overall, the papers examined show that governments in both donor and recipient countries need to ensure that behavioural change analysis is always part of development initiatives, so that new bottlenecks forming at the grassroots level can be quickly identified and managed.

A significant proportion of DAH is funded through NGOs in recipient countries. As such, NGOs need to have robust mechanisms to monitor fund allocation and measure impact. In many countries, NGOs are particularly helpful in funding health areas that may be considered taboo, such as sexual and reproductive well-being,[67] and a crackdown on NGOs could have a crippling impact on community-based health services.[68]

Depending on global financial conditions, DAH can fluctuate considerably each year. Recipient country governments try to overcome this volatility by strategising ways to self-finance by raising taxes on hedonistic activities or on financial transactions, or by drawing in private financing through social impact bonds, a situation described as ‘reverse fungibility’.[69],[70] ,[71] However, this usually results in less flexible budget lines, and if the financial replacement is only partial, it may punish the entire health sector due to underinvestment in health priorities.[72]

Fluctuations in currency exchange rates also lead to volatility in DAH, impacting the predictability and effectiveness of health services in recipient countries.[73] Institutionalising reporting standards to eliminate confusion generated by different aggregates and data sources could be the first step to preventing erroneous claims about aid volatility in academia.[74] This resonates with the need for improved data. However, relying on analyses of commitments to critique volatility is not entirely appropriate since commitments are promises for the future. If disbursement is the only factor assessed, fluctuations do not appear as distressing.[75]

While some scholars have expressed concerns over the fungibility of government investment and foreign assistance, there is no comprehensive evidence of whether it was detrimental to a country’s development. The provision of regular aid in any sector makes the state withdraw its resources, leaving it vulnerable to assistance volatility.[76] Governments allocate foreign aid to specific health programmes, redirecting their own funds to other areas of the healthcare system. However, while the displacement of government spending by DAH might occur in some settings, the evidence of it happening is not robust and highly varied across countries. As such, policymaking should not solely rely on current evidence about aid displacement.[77]

DAH funding priorities have shifted over the years. While this is desirable depending upon each country's varied disease burden, tackling a disease comprehensively before redirecting priorities is also crucial to avoid unintended consequences and ensure sustained progress towards eliminating it.[78] Some diseases that lie outside the scope of specific vertical funding mechanisms get overlooked, which may have negative public health consequences.

In recent years, literature has emerged focusing on areas that need more DAH funding, such as mental health. To make DAH in mental health more robust, mental disorders should be included in governmental priorities of low- and middle-income countries, and domestic spending on them should incrementally increase. Some papers noted that countries with a high proportion of migrant-to-native populations are less likely to be concerned about mental health, but this was overcome. Prosperous countries are more likely to adopt a mental health policy, and those without such strategies must consider adopting focused policies on this front. Mental health needs also increase during humanitarian emergencies, and DAH should consider this aspect.[79]

Another emerging area is diseases that affect older populations. Ensuring DAH funding begins to focus on this will help adapt to changes in the disease burden over time effectively.[80]

Climate change is also significantly affecting public health but has thus far not been considered when DAH is allocated[81] Given the imperative of climate change, climate consciousness must play a key role in such allocation.

Conclusion

Research and knowledge creation in health aid are crucial for better-informed DAH. However, research output on DAH has declined since 2017. The urgency of rectifying this decline is heightened by unprecedented health emergencies and escalating conflicts worldwide.

By assessing published research over the 2000-2021 period, this paper has identified many research gaps and disparities. For example, a mere 4 percent of the papers are focused on NGOs, philanthropies, and private businesses, despite these entities accounting for almost 20 percent of DAH. Additionally, few papers concentrated on specific health focus areas (such as strengthening health systems and infectious and vector-borne diseases) despite a significant amount of funding being allocated to them. Notably, most of the research is generated by high-income countries; while there is substantial literature on DAH recipients, most of it comes from scholars in the donor countries. More contributions from the recipients of DAH would make future research more representative and improve health policymaking, both among recipient and donor countries.

Bibliometric analysis is a useful tool for literature review and collation of policy recommendations in the field of public policy. Sites of knowledge creation and differences between these sites can present skewed representations in research. Such studies can provide context about the political economy surrounding knowledge creation. They can flag gaps in research, such as the dearth of research on impact evaluation and growth of private organisations in DAH. Combined with other methods, such as text analysis, bibliometric analysis can also provide a snapshot of existing research themes, topics, and concerns, particularly in niche areas. These snapshots can provide preliminary insights into global research and can be fashioned to understand contextual gaps.

This study encountered some critical limitations. Firstly, not all DAH donors publish their impact evaluations in scientific journals, and some may not even conduct impact evaluation studies. This may be due to a variety of reasons, including inconsistent data and a lack of capacity to conduct such evaluations. Secondly, impact evaluation studies conducted by the donor and recipient countries and organisations may be confidential. Thirdly, publishing in scientific journals may not be affordable for researchers in lower-middle- or low-income countries since conducting research may be expensive or journals may not compensate for the research. While there are various research funding initiatives, they may not always be accessible to researchers from these countries.

This study has raised questions and avenues for further research. This includes assessing the cause for the decline in research output in the field of DAH since 2017, analysing lessons and learnings in aid effectiveness or aid appropriateness, and bibliometric analysis of a particular health area or one country’s experience (such as India’s development partnership model in DAH) for further insights.

Endnotes

[a] Prioritising medical needs, infrastructure, and healthcare services over focusing on other concerns, such as providing relief or capacity building.

[b] H-Index measures a research scholar’s productivity, based on the number of papers published and the number of times other researchers cited them.

[c] The importance or rank of a journal, based on calculating the times its articles are cited.

[d] These papers explicitly mentioned health or foreign policy and governance in their titles and meshes, but do not include the papers that may have related policy recommendations in their findings and conclusion.

[e] GHIs are humanitarian initiatives that raise and disburse additional funds for infectious diseases for immunisations and to strengthen health systems in recipient countries.

[f] The Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness outlines five fundamental principles for making aid more effective: ownership, alignment, harmonisation, results, and mutual accountability.

[g] The probe into the Cashgate scandal found that government employees in Malawi had manipulated the payment system to steal around US$32 million from the treasury in about six months.

1 Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), “Development Assistance for Health Database 1990-2021,” 2023.

2 T. Jacob John and Vipin M. Vashishtha, “Eradicating Poliomyelitis: India’s Journey from Hyperendemic to Polio-Free Status,” The Indian Journal of Medical Research 137, no. 5 (2013).

3 Edward A. Banchani and Liam Swiss, “The Impact of Foreign Aid on Maternal Mortality,” Politics and Governance 7, no. 1 (2019), https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v7i2.1835

4 Martin Gerdin et al., “Does Need Matter? Needs Assessments and Decision-Making Among Major Humanitarian Health Agencies,” Disasters 38, no. 3 (2014), https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12065

5 Michelle C. Dimitris, Matthew Gittings, and Nicholas B. King, “How Global is Global Health Research? A Large-Scale Analysis of Trends in Authorship,” BMJ Global Health 6, no. 1 (2021), https://gh.bmj.com/content/6/1/e003758

6 Athula Sumathipala et al., “Under-Representation of Developing Countries in the Research Literature: Ethical Issues Arising from a Survey of Five Leading Medical Journals,” BMC Medical Ethics 5, no. 1 (2004), https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6939-5-5

7 James Deane, “Media and Communication in Governance: It’s Time for a Rethink,” OECD, 2015.

[8] Naveen Donthu et al., “How to Conduct a Bibliometric Analysis: An Overview and Guidelines,” Journal of Business Research 133 (September 1, 2021): 285–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.070

9 Christopher J. L. Murray et al., Financing Global Health 2012: The End of the Golden Age?, Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2012.

10 Eran Bendavid and Jay Bhattacharya, “The Relationship of Health Aid to Population Health Improvements,” JAMA Internal Medicine 174, no. 6 (2014), 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.292

11 Valentina Iemmi, “Global Collective Action in Mental Health Financing: Allocation of Development Assistance for Mental Health in 142 Countries 2000-2015,” Social Science & Medicine 287 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114354

12 Laura E. Tesler and Ruth E. Malone, “Corporate Philanthropy, Lobbying, and Public Health Policy,” American Journal of Public Health 98, no. 12 (2008), 2123-33.

13 Roose Lambin and Rebecca Surender, “The Rise of Big Philanthropy in Global Social Policy: Implications for Policy Transfer and Analysis,” Journal of Social Policy 52, no. 3 (2023), https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279421000775

14 Kent Buse, “Keeping a Tight Grip on the Reins: Donor Control Over Aid Coordination and Management in Bangladesh,” Health Policy and Planning 14, no. 3 (1999).

15 David McCoy, Sudeep Chand, and Devi Sridhar, “Global Health Funding: How Much, Where it Comes from and Where it Goes,” Health Policy and Planning 24, no. 6 (2009), https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czp026

[16] Nisha Ravishankar et al., “Financing of Global Health: Tracking Development Assistance for Health from 1990 to 2007,” The Lancet 373, no. 9681 (2009), https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60881-3

17 Jessica Goldberg and Malcolm Bryant, “Country Ownership and Capacity Building: The Next Buzzwords in Health Systems Strengthening or a Truly New Approach to Development?” BMC Public Health 12, no. 1 (2012), https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-531

18 Ravishankar et al., “Financing of Global Health”

19 Valeria Oliveira Cruz and Barbara McPake, “The ‘Aid Contract’ and its Compensation Scheme: A Case Study of the Performance of the Ugandan Health Sector,” Social Science & Medicine 71, no. 7 (2010), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.06.036

20 McCoy, Chand, and Sridhar, “Global Health Funding”

21 Ronald Labonté, “The Global Financial Crisis and Health: Scaling Up Our Effort,” Canadian Journal of Public Health 100, no. 3 (2009), https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03405534

22 Devi Sridhar, “Seven Challenges in International Development Assistance for Health and Ways Forward,” Journal of Law Medicine & Ethics 38, no. 3 (2010), https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-720x.2010.00505.x

23 Rebecca Dodd et al., “Strengthening and Measuring Research Impact in Global Health: Lessons from Applying the FAIT Framework,” Health Research Policy and Systems 17, no. 1 (2019), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-019-0451-0

24 Lu Han, Mathias Koenig-Archibugi, and Tore Opsahl, “The Social Network of International Health Aid,” Social Science & Medicine 206 (2018), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.04.003

25 Olivier Sterck et al., “Allocation of Development Assistance for Health: Is the Predominance of National Income Justified?” Health Policy and Planning 33, no. 1 (2018), https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czw173

26 Elizabeth Stierman, Freddie Ssengooba, and Sara Bennett, “Aid Alignment: A Longer-Term Lens on Trends in Development Assistance for Health in Uganda,” Globalization and Health 9, no. 1 (2013), https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8603-9-7

[27] Sterck et al., “Allocation of Development Assistance for Health”

28 Tim B. Heaton et al., “Social Inequality and Children’s Health in Africa: A Cross-Sectional Study,” International Journal for Equity in Health 15, no. 92 (2016), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-016-0372-2

[29] Fumitaka Furuoka et al., “An Analysis of the Development Assistance for Health (DAH) Allocations for STD Control in Africa,” Health Economics Policy and Law 15, no. 4 (2019), https://doi.org/10.1017/s1744133119000197

[30] Thomas W. Croghan, Amanda Beatty, and Aviva Ron, “Routes to Better Health for Children in Four Developing Countries,” The Milbank Quarterly 84, no. 2 (2006), https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2006.00450.x

[31] Han, Koenig-Archibugi, and Opsahl, “The Social Network of International Health Aid”

[32] Radha Adhikari et al., “Foreign Aid, Cashgate and Trusting Relationships Amongst Stakeholders: Key Factors Contributing to (Mal)functioning of the Malawian Health System,” Health Policy and Planning 34, no. 3 (2019), https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czz021

[33] Nabyonga Orem Juliet , Ssengooba Freddie, and Sam Okuonzi, “Can Donor Aid for Health be Effective in a Poor Country? Assessment of Prerequisites for Aid Effectiveness in Uganda,” The Pan African Medical Journal, 3, no. 1 (2010), https://doi.org/10.4314/pamj.v3i1.52448

[34] Labonté, “The Global Financial Crisis and Health”

[35] Joseph L. Dieleman and Michael Hanlon, “Measuring the Displacement and Replacement of Government Health Expenditure,” Health Economics 23, no. 2 (2014), https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3016

[36] Eduardo Missoni et al., “Italy’s Contribution to Global Health: The Need for a Paradigm Shift,” Globalization and Health 10, no. 25 (2014), https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8603-10-25

[37] Vin Gupta et al., “Has Development Assistance for Health Facilitated the Rise of More Peaceful Societies in Sub-Saharan Africa?” Global Public Health 13, no. 12 (2018), https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2018.1449232

[38] Samer Al-Bader et al., “Science-Based Health Innovation in Sub-Saharan Africa,” BMC International Health and Human Rights 10, no. 1 (2010), https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-698x-10-s1-s1.

[39] Valeria Oliveira Cruz and Barbara McPake, “The ‘Aid Contract’ and its Compensation Scheme: A Case Study of the Performance of the Ugandan Health Sector,” Social Science & Medicine 71, no. 7 (2010), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.06.036

[40] Parveen Parmar et al., “Health and Human Rights in Eastern Myanmar after the Political Transition: A Population-Based Assessment Using Multistaged Household Cluster Sampling,” PLOS ONE 10, no. 5 (2015), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0121212

[41] Tamara Fetters et al., “Navigating the Crisis Landscape: Engaging the Ministry of Health and United Nations Agencies to Make Abortion Care Available to Rohingya Refugees,” Conflict and Health 14, no. 1 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-020-00298-6

[42] Berit Austveg and Johanne Sundby, “Norway at ICPD+10: International Assistance for Reproductive Health Does Not Reflect Domestic Policies,” Reproductive health matters 13, no. 25 (2005), https://doi.org/10.1016/s0968-8080(05)25169-8

[43] Suerie Moon and Oluwatosin Omole, “Development Assistance for Health: Critiques, Proposals, and Prospects for Change,” Health Economics Policy and Law 12, no. 2 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1017/s1744133116000463

[44] Shuang Lin et al., “China’s Health Assistance to Africa: Opportunism or Altruism?” Globalization and Health 12, no. 1 (2016), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-016-0217-1

[45] L. C. Goe and J. A. Linton, “Community-Based Public Health Interventions in North Korea: One Non-Governmental Organization’s Experience with Tuberculosis and Hepatitis B,” Public Health 119, no. 5 (2005), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2004.05.024

[46] Allison Baer Alley et al., “Republic of Korea’s Health Aid Governance: Perspectives from Partner Countries,” Journal of Korean Medical Science 30, no. 2 (2015), https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2015.30.s2.s149

[47] Irene A. Agyepong et al., “The Path to Longer and Healthier Lives for All Africans by 2030: The Lancet Commission on the Future of Health in Sub-Saharan Africa,” The Lancet 390 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)31509-x

[48] Rita Giacaman, Hanan F Abdul-Rahim, and Laura Wick, “Health Sector Reform in the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT): Targeting the Forest or the Trees?” Health Policy and Planning 18, no. 1 (2003), https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/18.1.59

[49] Renata Konrad, Kalyna Bezchlibnyk-Butler, and Marika Dubyk Wodoslawsky, “Allocation of Aid for Health Institutions in Ukraine: Implications from a Case Study of Chornobyl (Chernobyl) Area Hospitals,” International Journal of Health Services 39, no. 4 (2009), https://doi.org/10.2190/hs.39.4.b

[50] Johanna Hanefeld and Maurice Musheke, “What Impact Do Global Health Initiatives Have on Human Resources for Antiretroviral Treatment Roll-Out? A Qualitative Policy Analysis of Implementation Processes in Zambia,” Human Resources for Health 7, no. 1 (2009), https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-7-8

[51] Marie N. Fongwa, “International Health Care Perspectives: The Cameroon Example,” Journal of Transcultural Nursing 13, no. 4 (2002), https://doi.org/10.1177/104365902236708

[52] Rajeev J. Limaye et al., “Blended Learning on Family Planning Policy Requirements: Key Findings and Implications for Health Professionals,” BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health 44, no. 2 (2018), https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsrh-2017-101752

[53] Joseph L. Dieleman et al., “Future and Potential Spending on Health 2015–40: Development Assistance for Health and Government, Prepaid Private and Out-of-Pocket Health Spending in 184 Countries,” The Lancet 389, no. 10083 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)30873-5

[54] Caroline A. Taylor, Frances Griffiths, and Richard Lilford, “Affordability of Comprehensive Community Health Worker Programmes in Rural Sub-Saharan Africa,” BMJ Global Health 2, no. 3 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000391

[55] Vasudeva N. R. Murthy and Albert A. Okunade, “The Core Determinants of Health Expenditure in the African Context: Some Econometric Evidence for Policy,” Health Policy 91, no. 1 (2009), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.10.001

[56] Taylor, Griffiths, and Lilford, “Affordability of Comprehensive Community Health Worker Programmes in Rural Sub-Saharan Africa”

[57] Han, Koenig-Archibugi, and Opsahl, “The Social Network of International Health Aid”

[58] Gorik Ooms and Rachel Hammonds, “Global Constitutionalism, Responsibility to Protect and Extra-Territorial Obligations to Realize the Right to Health: Time to Overcome the Double Standard (Once Again),” International Journal for Equity in Health 13, no. 1 (2014), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-014-0068-4

[59] Ooms and Hammonds, “Global Constitutionalism, Responsibility to Protect and Extra-Territorial Obligations to Realize the Right to Health”

[60] Isabel Craveiro and Gilles Dussault, “The Impact of Global Health Initiatives on the Health System in Angola,” Global Public Health 11, no. 4 (2016), https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2015.1128957

[61] Sarah W. Pallas et al., “Responses to Donor Proliferation in Ghana’s Health Sector: A Qualitative Case Study,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 93, no. 1 (2015), https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.14.141614

[62] Cedric R. S. Nguefack, “Effectiveness of Official Development Assistance in the Health Sector in Africa: A Case Study of Uganda,” The International Quarterly of Community Health Education, 41, no. 3 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1177/0272684x20918045

[63] Adhikari et al., “Foreign Aid, Cashgate and Trusting Relationships Amongst Stakeholders”

[64] Lameck Masina, “Malawi: Donors Withhold Aid Over Cashgate Scandal,” Voice of America News, November 7, 2013, https://www.voanews.com/a/malawi-donors-withhold-aid-over-cashgate-scandal/1786120.html

[65] Modhurima Moitra et al., “Factors Associated with the Disbursements of Development Assistance for Health in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries 2002–2017,” BMJ Global Health 6, no. 4 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004858

[66] Dieleman and Hanlon, “Measuring the Displacement and Replacement of Government Health Expenditure”

[67] Sara Seims, “Improving the Impact of Sexual and Reproductive Health Development Assistance from the Like-minded European Donors,” Reproductive Health Matters 19, no. 38 (2011), https://doi.org/10.1016/s0968-8080(11)38578-3

[68] Dintle Molosiwa, Tyanai Masiya, and Godfrey Maringira, “Management of the Global Fund Aid Programme in Botswana: Challenges and Prospects for Health Services Delivery,” African Journal of AIDS Research 18, no. 2 (2019), https://doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2019.1605396

[69] Rima Shretta et al., “Tracking Development Assistance and Government Health Expenditures for 35 Malaria-Eliminating Countries: 1990–2017,” Malaria Journal 16, no. 1 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-017-1890-0

[70] Collins Chansa, Jesper Sundewall, and Numi Östlund, “Effect of Currency Exchange Rate Fluctuations on Aid Effectiveness in the Health Sector in Zambia,” Health Policy and Planning 33, no. 7 (2018), https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czy046

[71] Nathalie Van de Maele, David B. Evansa, and Tessa Tan-Torres, “Development Assistance for Health in Africa: Are Ee Telling the Right Story?” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 91, no. 7 (2013), 483–90. https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.12.115410

[72] Dieleman and Hanlon, “Measuring the Displacement and Replacement of Government Health Expenditure”

[73] Chansa, Sundewall, and Östlund, “Effect of Currency Exchange Rate Fluctuations on Aid Effectiveness in the Health Sector in Zambia”

[74] Van de Maele, Evansa, and Tan-Torres, “Development Assistance for Health in Africa”

[75] Dieleman and Hanlon, “Measuring the Displacement and Replacement of Government Health Expenditure”

[76] Melisa Martínez Álvarez et al., “Is Development Assistance for Health Fungible? Findings from a Mixed Methods Case Study in Tanzania,” Social Science & Medicine 159 (2016), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.05.006

[77] Rajaie Batniji and Eran Bendavid, “Does Development Assistance for Health Really Displace Government Health Spending? Reassessing the Evidence,” PLOS Medicine 9, no. 5 (2012), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001214

[78] Dieleman et al., “Future and Potential Spending on Health 2015–40”

[79] Iemmi, “Global Collective Action in Mental Health Financing”

[80] Vegard Skirbekk et al., “Vast Majority of Development Assistance for Health Funds Target Those Below Age Sixty,” Health Affairs 36, no. 5 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1370

[81] Florian Weiler, “Adaptation and Health: Are Countries with More Climate-sensitive Health Sectors More Likely to Receive Adaptation Aid?” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 8 (2019), https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16081353

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Ovee is a Research Associate at CPC Analytics. She has done her bachelor's in Literary and Cultural Studies and is interested in understanding power oppression ...

Read More +

Rishab Jain is a third-year undergraduate student at FLAME University. He specialises in Business Analytics and Economics. He is passionate about integrating statistics, machine learning, ...

Read More +

Non-resident fellow at ORF. Sahil Deo is also the co-founder of CPC Analytics, a policy consultancy firm in Pune and Berlin. His key areas of interest ...

Read More +