In 2000, advanced economies accounted for 48 percent of global coal consumption while China and India together accounted for 35 percent. Natural gas began displacing coal in the EU (European Union) and in the 1980s and in the USA in the 2000s. Coal demand has increased in Asia in general and India and China in particular since the 2000s. The International Energy Agency (IEA) expects China and India to account for more than 70 percent of global coal consumption by 2026. India has set a target to increase coal production to 1 billion tonnes (BT) by 2030. Coal demand is expected to increase to 1,192-1,325 Million Tonnes (MT) by 2030. In 2022, India’s coal consumption accounted for 14 percent of global demand, second after China, which accounted for 54 percent of global coal consumption. The IEA expected China’s coal demand to peak in 2023 while Sinopec, a state-owned Chinese oil company has forecast China’s coal consumption to peak in 2025. The Ministry of Coal (MoC), Government of India, expects coal demand in India to peak in 2030-35. The growth of coal production is showing signs of decline. If this trend continues India may hit peak coal in the early 2030s as forecasted.

Domestic Coal Production

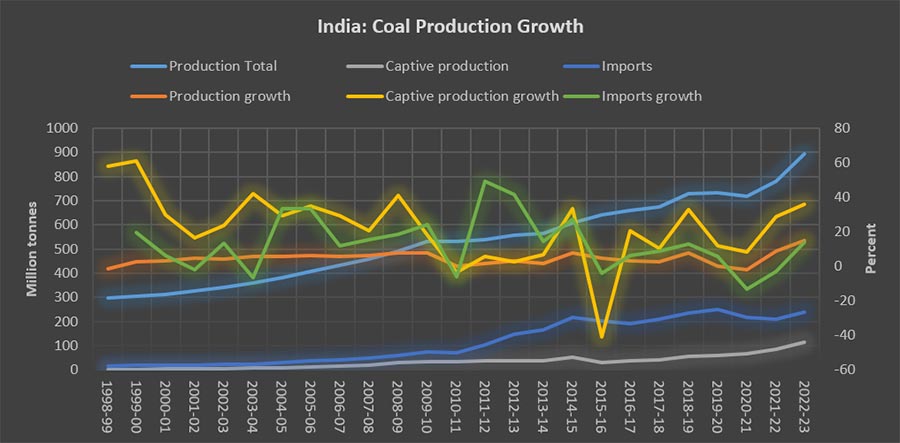

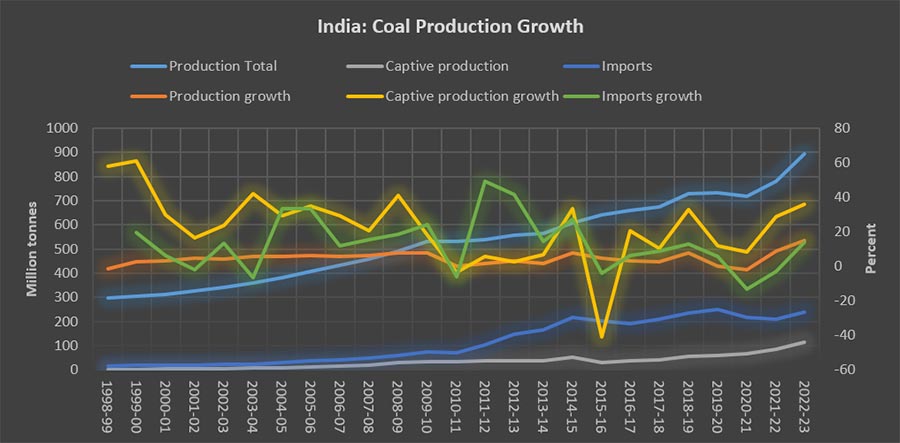

In the last 25 years (since 1998-99), domestic coal production (coking and non-coking) grew by an annual average of 4.5 percent.[1] In the decade ending in March 2013, coal production grew by about 5 percent, and in the decade ending in March 2023, domestic coal production grew by 4.8 percent. The slowdown in production in the decade ending in March 2023 is not difficult to explain. Captive coal blocks allocated to the private sector in the previous decade were cancelled and auctioned to the private sector in the following decade (beginning in 2014) with the expectation that the captive and commercial production from mines auctioned to the private sector will contribute substantially to domestic production. However, after the cancellation of coal block allocations in 2015-16 captive coal production by the private sector decreased by an annual average of over 41 percent. In 2016-17, domestic coal production slowed down to 2.9 percent from 4.9 percent the previous year and remained low at 2.7 percent the following year (2017-18). The demonetisation of currency notes announced in 2016 could have also contributed to the slowdown in coal production, as activities in the informal economy were curtailed. In 2019-20, the pandemic slowed down coal production growth to an annualised 0.3 percent. In the peak pandemic year of 2020-21 coal production decreased by an annual average of 2 percent. Since 2021-22, coal production growth has revived. In 2021-22, coal production increased by 8.6 percent and by 14.8 percent in 2022-23.

Captive Coal Production

Captive coal production in the late 90s demonstrated exponential growth until the early 2010s. From 1998-99 to 2008-09, coal production from captive mines allocated to the private sector grew by an annual average of over 30 percent. From 2002-03 to 2012-13, coal production from auctioned mines grew by an annual average of about 20.9 percent and in 2012-13 to 2022-23, it grew by an annual average of about 12 percent. In 2022-23, coal production from mines auctioned to the private sector grew by an annualised rate of 36 percent. It is likely that coal production from auctioned mines continue to grow at double-digit rates in the current decade.

Imports

When the economy was partially opened up in the 1990s, demand for power accelerated, and coal was put under open general licence (OGL) in 1993 which initiated thermal coal imports. Until the mid-2000s, the volume of coking coal imports exceeded the volume of thermal coal imports. This changed in 2005-06 when India imported 21.70 MT of thermal coal compared to 16.89 MT of coking coal. It was attributed to consumer (thermal power generators) preference for coal quality. Thermal coal imports accelerated with the construction of imported coal-based coastal power plants. Between 1998-99 and 2022-23, coking coal imports increased from about 10.02 MT to 56.05 MT, more than a fourfold increase, while the import of non-coking (thermal) coal experienced a twentyfold increase in the same period. Total coal imports in the decade 2002-03 to 2012-13 increased by an annual average of over 20 percent while it increased only by an annual average of about 5 percent in the decade 2012-13 to 2022-23. In the decade ending in March 2023 import of coking coal increased by an annual average of over 10 percent while the import of non-coking coal increased by an annualised rate of over 26 percent. In the decade ending in March 2023, the annual average growth rate of coking coal imports was over 3 percent while growth of imports of non-coking coal was over 5 percent.

Key Takeaways

Coal production (both coking and non-coking coal) in the decade before March 2013 and in the decade after 2013 reveals the impact of the shift in policy. One key policy change between the two decades was the replacement of the system of allocating coal blocks to the private sector with the system of auctioning coal blocks to the private sector. The government also set clear targets for domestic coal production. In 2019, the Minister for Coal announced that Coal India Limited (CIL) should produce 1 BT of coal by 2023-24. The target is yet to be achieved. However domestic coal production grew at a much faster rate in the decade prior to the change in policy than after the policy change. This is particularly true in the case of production by the private sector as noted earlier. Import of coal (coking and non-coking) also demonstrated a faster growth rate in the decade prior to March 2013 than in the decade after March 2013. One of the explanations could be that coal production was more responsive to economic fundamentals of supply and demand than to policy shifts. Economic growth in the decade after March 2013 was slower than that in the decade before March 2013. Growth in coal production was negative after demonetisation in 2016 and during the pandemic in 2019-20 to 2021-22. Another possible explanation is the shift towards renewables that is slowing down demand for coal. If that is indeed the case one could say that the energy transition is making slow but steady progress and India may be well on its way to hitting the target for peak coal in the 2030s.

Source: Coal Directories 2004-2021, Coal Controllers Office, Ministry of Coal

Lydia Powell is a Distinguished Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation.

Akhilesh Sati is a Program Manager at the Observer Research Foundation.

Vinod Kumar Tomar is a Assistant Manager at the Observer Research Foundation.

[1] Coal directories published by the Coal Controllers Office (CCO) are no longer available on the website of the CCO. The reports were downloaded and saved earlier.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV