Introduction

In May 2023, the University Grants Commission (UGC), a statutory body that oversees higher education in India, released draft guidelines to regulate the entry and operation of foreign higher educational institutions (FHEIs) in the country, an idea that stems from the 2020 National Education Policy (NEP) that seeks to reform education in India.[1] The UGC will set up a standing committee to scrutinise and approve applications by FHEIs interested in operating in India based on the following essential guidelines:

- FHEIs interested in operating in India must rank among the top 500 global universities. While the ranking method is not specified, it will likely be as per the Times Higher Education World University Ranking or QS World University Ranking.[a] The UGC will grant approvals for a 10-year period, which can be extended. The approved FHEIs must pay an annual fee (currently unspecified) to the UGC to operate in India.

- FHEIs can have their own selection criteria for Indian and international students. The fees should be “transparent and reasonable,” and the institute “may” offer need-based scholarships.

- FHEIs can recruit faculty and staff from India or abroad on any salary, provided their qualification is “at par” with the home campus faculty. If appointed, foreign faculty must stay at the Indian campus “for a reasonable period”.

- The quality of the education at the FHEIs must be “at par” with that at the home campus. However, the guidelines do not specify what this ‘quality’ entails.

- FHEIs cannot conduct online or open and distance learning programmes.

- The degrees and certifications granted at the FHEI campus must be equivalent to and recognised by the home campus.

- FHEIs should not promote programmes that encourage studying at the home campus.

The decision to allow FHEIs to operate in India appears to be driven by three factors. The first is to offer high-quality higher education to Indian students who are otherwise compelled to go abroad. Indian universities typically do not figure in global university rankings. As Indian youth increasingly aspire for high-quality higher education, they are forced to seek such options in foreign countries. In 2022, nearly 1 million Indian students moved to foreign countries to study.[2] Indian students pursuing education opportunities abroad results in a ‘brain drain’ for the country and substantial costs for students and their families through high fees and living expenses. As such, the draft UGC regulations appear to be seeking to arrest the significant outflow of capital and young people from India. Second, India is seeking to attract reputed FHEIs and build an ecosystem of high-quality teaching and research in the country. Third, India has only a handful of private universities that have the potential to become world-class universities. Allowing FHEIs to operate in India will increase competition and compel emerging private universities to build capacity and enhance quality. However, while several of the regulatory clauses in the draft guidelines engage with university student recruitment and fees, there is scarce reference to collaboration or research infrastructure.

Still, there is little clarity on whether reputed foreign universities are interested in setting up campuses in India and how these regulations will impact the country’s higher education sector. While the UGC regulations reflect a shift in the Indian government's mindset (a welcome sign), simply allowing FHEIs to operate in India is unlikely to address the concerns that ostensibly led to the guidelines being established. This paper attempts to address this by examining the establishment of FHEIs in China, South Korea, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Malaysia to arrive at learnings for India.

Assessing Global Experiences

Given the relatively small number of FHEIs worldwide, there is little research on the perceived benefits of and issues with establishing such institutions. Another possible reason is that research on universities’ expansion is typically to understand knowledge spillovers more than the university-specific attributes.[3] When considering establishing FHEIs, individual universities require more nuanced and contextual information focused on business strategies and risks, much of which remains unexplored.[4] FHEIs represent an advanced stage of the globalisation of higher education, are symbolic of a churn in the sector, and, as such, require a deeper look.[5]

FHEIs are a relatively recent phenomenon. There were only five FHEIs worldwide until 1970, rising to 82 by 2006 and 200 in 2011.[6] Indeed, FHEIs began to proliferate in the 2000s due to increased collaborations between countries, economic growth in developing countries, and improved means of communication.[7] Still, research remains limited. Between 2000 and 2017, only 173 publications engaged with the idea of and issues related to FHEIs, with 113 journal articles (or 65 percent of the total output).[8] Most of these studies focused on managerial and academic staff issues and educational hubs, leaving a considerable gap in developing a comprehensive understanding of FHEIs.

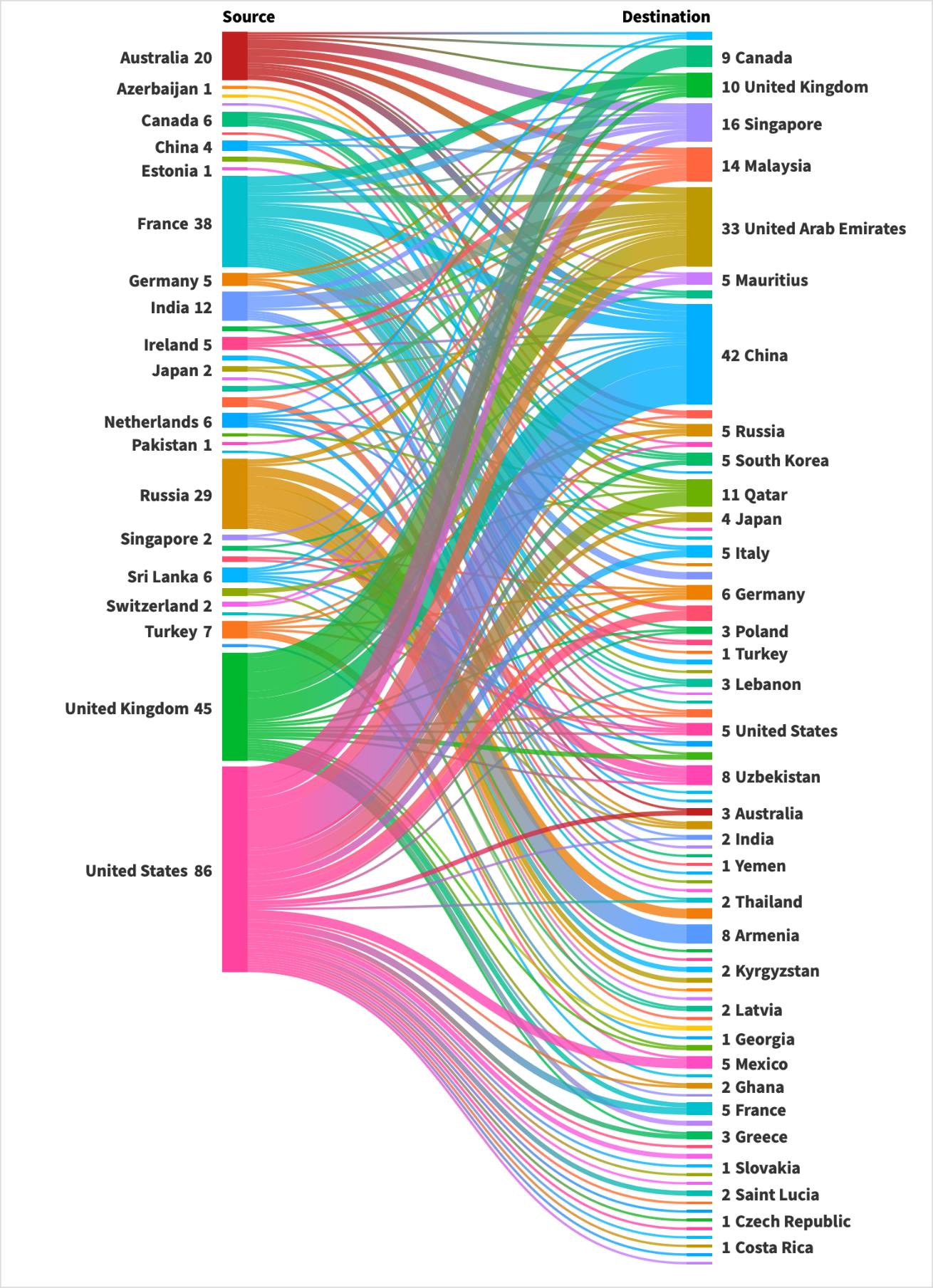

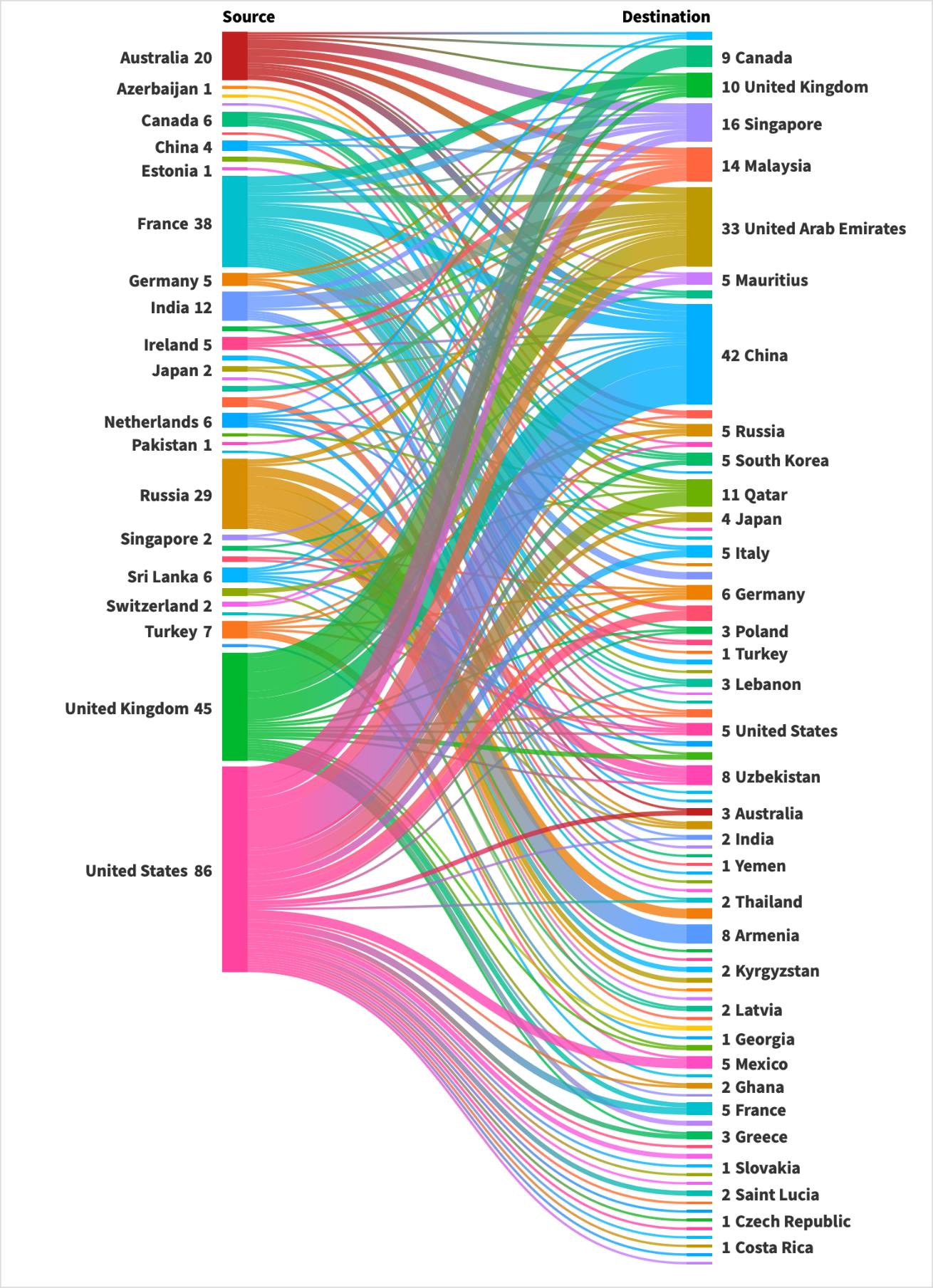

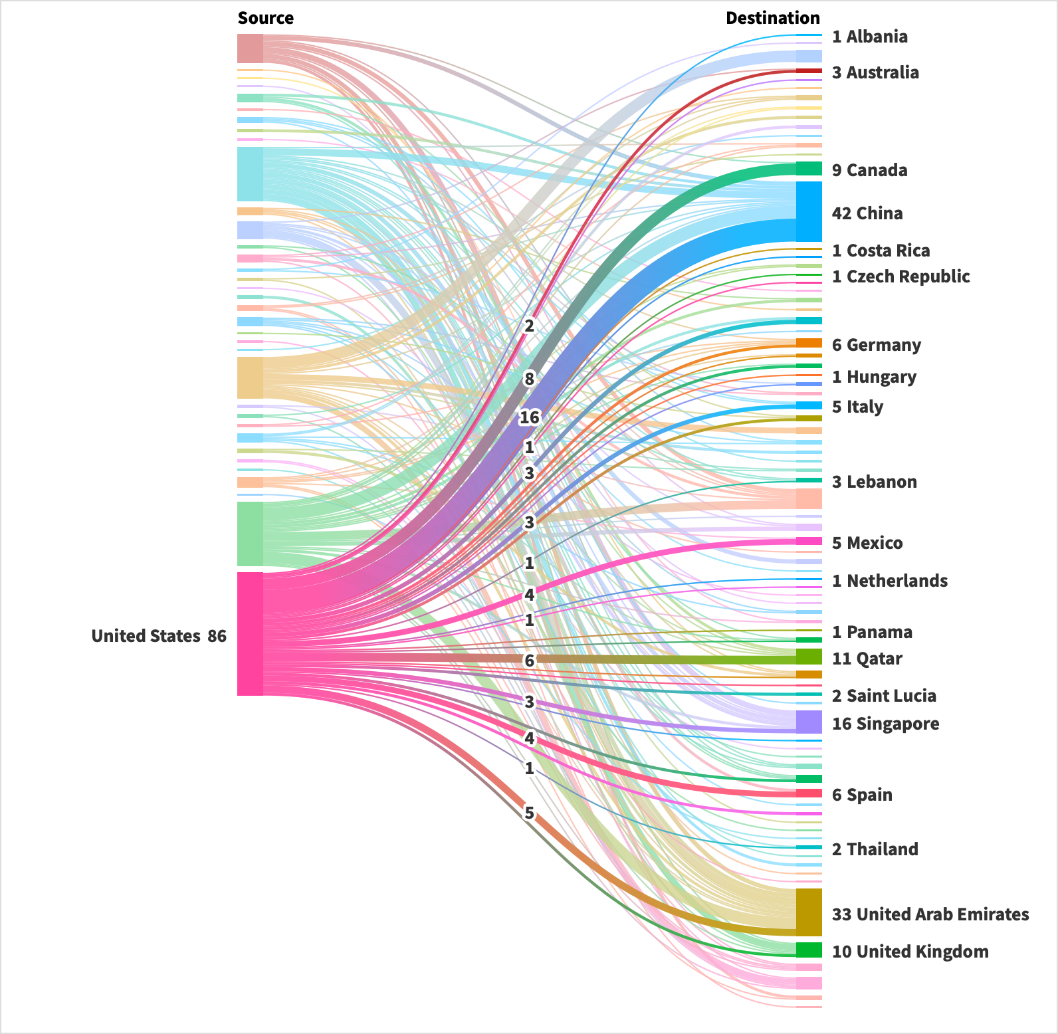

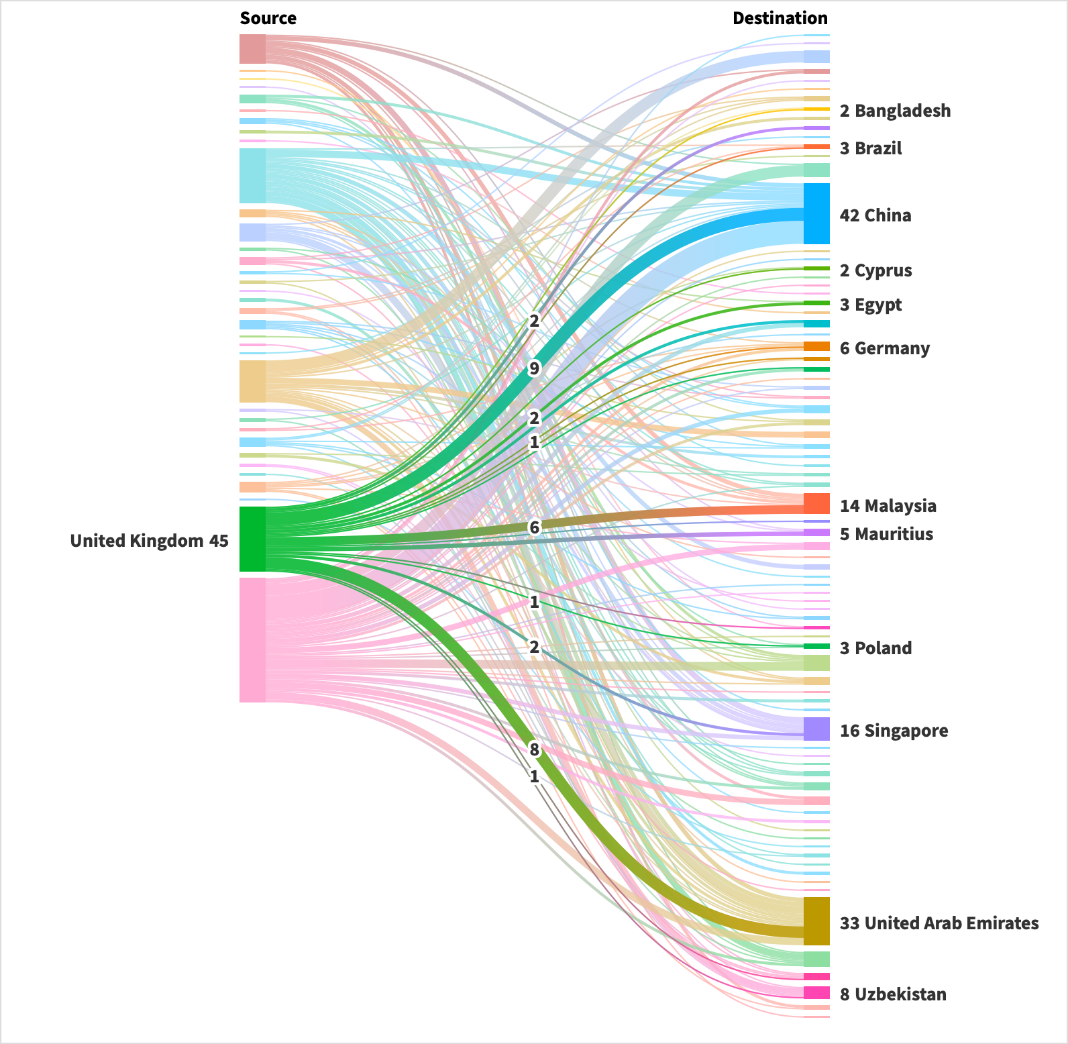

As of March 2023, there are 333 FHEIs worldwide, with the US the largest ‘exporter’ of universities (accounting for 25 percent of such institutes), followed by the UK, France, and Russia (with between 11 percent and 14 percent). The biggest ‘importers’ are China (14 percent) and the UAE (9 percent), followed by Singapore, Malaysia, and Qatar (between 3 percent and 5 percent).[9] There is a higher concentration of ‘exporters’ than ‘importers’, signifying that FHEIs originate in a few countries even though they are thinly spread across many (Figures 1 and 2 demonstrate this flow in Sankey diagrams).

Figure 1: ‘Export’ and ‘import’ of universities globally

Source: Authors’ calculations using the C-BERT database.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the C-BERT database.

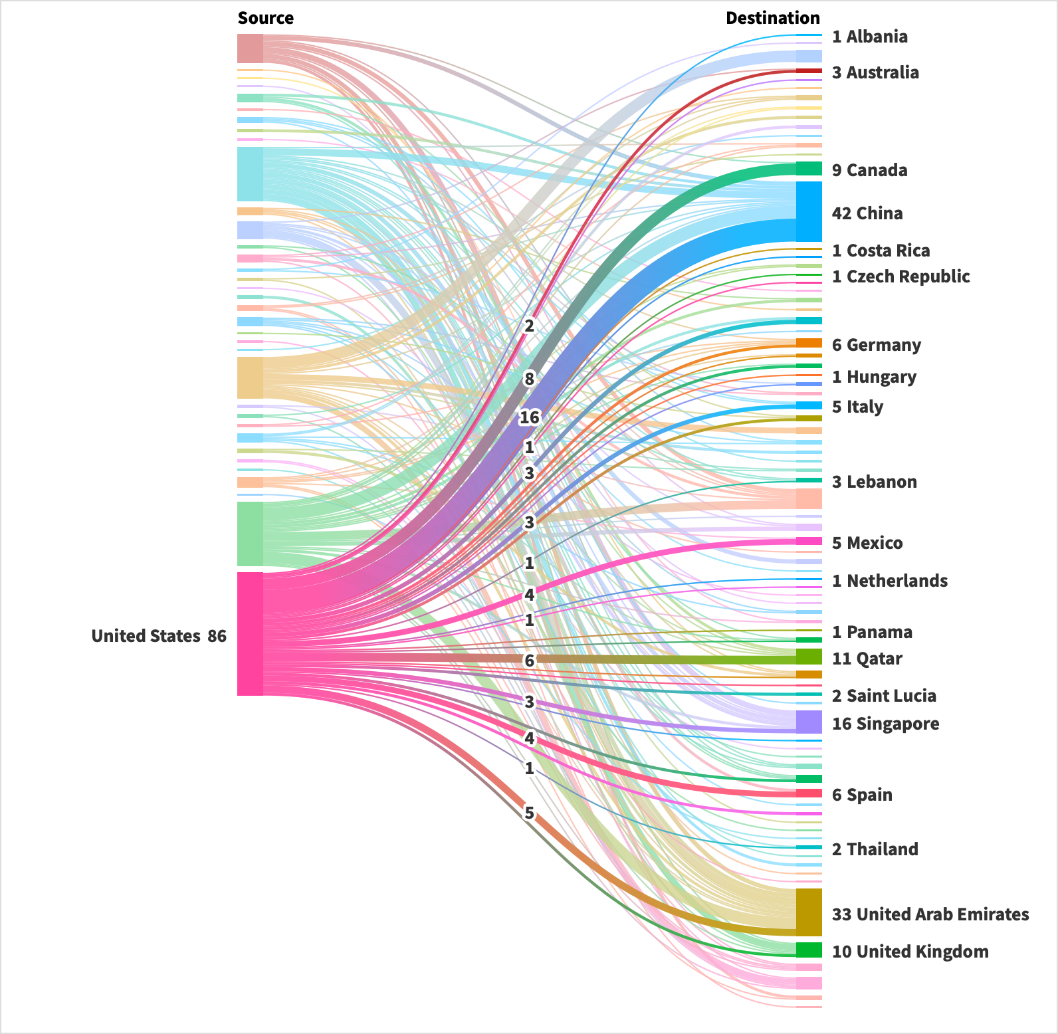

Figure 2 a: Flow of Higher Education Institutions from the US

Note: decomposed from Figure 1

Note: decomposed from Figure 1

Source: Authors’ calculations using the C-BERT database.

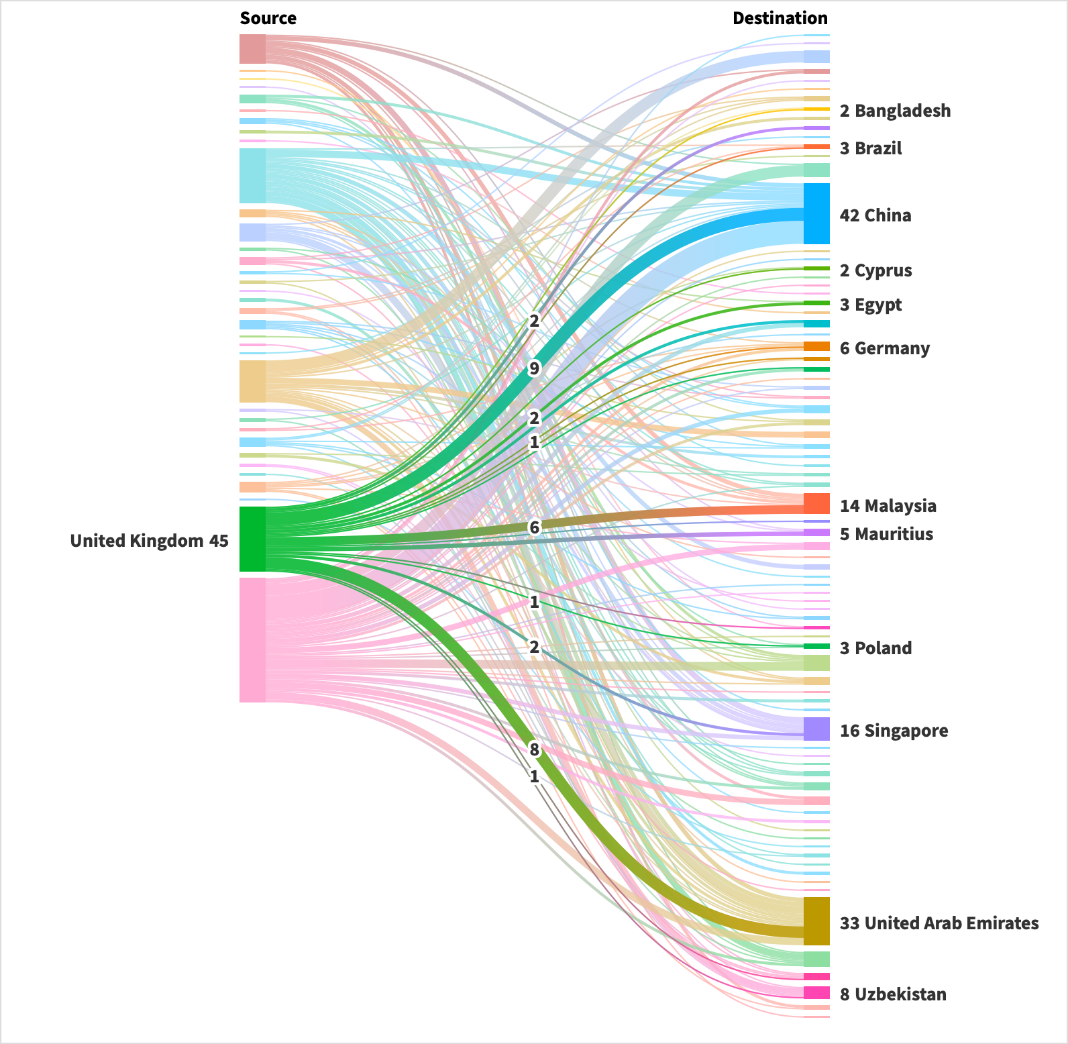

Figure 2 b: Flow of Higher Education Institutions from the UK

Note: decomposed from Figure 1

Note: decomposed from Figure 1

Source: Authors’ calculations using the C-BERT database.

The experiences of importing countries could provide some insights for India as it begins to allow FHEIs into its education sector. This paper presents a case study-based analysis of China and the UAE (the two largest host countries), South Korea (since it has a renowned rigorous education system), and Malaysia (which follows behind major players like China and the UAE in terms of imports). The paper assesses the structure, size, location, and fees of FHEIs from the UK and the US operating in the four countries (as specified on the websites of these institutes in the host country).

China

Higher education institutions (HEIs) in China were initially structured to meet the expectations of the country’s Soviet-style management system, characterised by centralisation, public ownership, strict hierarchies, and the politicisation of management.[10] However, with the launch of the New Era in 1978, the Chinese higher education system underwent a significant transformation to achieve the ‘Four Modernizations’: national defence, agriculture, science and technology, and industry.[11] The transformation of HEIs in China can be characterised by four vital components: commercialisation, decentralisation, expansion, and marketisation.[12]

The commercialisation aspect introduced a co-funding model between 1949 and 1988, which entailed sharing the cost of education between the government and students, with students not required to pay any fees and instead receiving financial support to cover their cost of living.[13] Beginning in 1988, the rapid expansion of higher education meant universities began to impose tuition fees, even as concerns regarding the adverse impact on students from less affluent families, particularly those from rural areas, persisted.[14] The second aspect of the reform process was the decentralisation of higher education, resulting in a critical distinction between elite and non-elite universities, with the former being administered by the Ministry of Education and the latter managed by provincial or local governments. The state retained control of prominent national universities (Project 211 universities) while the government continued establishing world-class universities (Project 985). This approach allowed the government to focus investments in high-impact areas and control the costs associated with expanding the scope of HEIs.[15] The third component of the reform process is the expansion of higher education. Between 1997 and 2006, the number of new students increased by 5.3 million, and the gross enrolment rate (GER) rose by 15 percent.[16] The final component of the reform process is marketisation, which refers to developing private non-state institutions called minban (community-sponsored). Minbans are classified into two categories: independent colleges affiliated with state universities, and transnational HEIs with overseas partners.[17]

The demand for education led to the development of China’s private and public education sectors, but the quality and prestige of higher education remained a concern. Partnering with foreign institutes was expected to enhance intellectual capacity and promote a holistic perspective on education within China.[18] In 2003, the State Council promulgated the Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Chinese-foreign Cooperative Education, which was revised in 2017. The regulations demonstrated China’s aspiration to adopt the practices of distinguished global universities and raise itself to be on par with international institutes. The most notable responses to this opportunity were the establishment of the University of Nottingham-Ningbo in 2004 and the Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University in 2006, as they aim to form research collaborations, educational networks, and initiatives in China. [19] Several institutions have since established partnerships in China.

Structure: Programmes offered by foreign institutions can be categorised as those that do not award degrees and those that lead to degrees from foreign universities or Hong Kong University. Foreign universities can only operate in China by establishing joint centres or collaborating with Chinese universities. Foreign universities or corporations are prohibited from creating branch campuses, except for the University of Nottingham-Ningbo, a collaboration between the UK’s University of Nottingham and China’s Zhejiang Wanli University. Moreover, other universities have yet to be conferred the status of a corporation as they are considered a supplementary part of the curriculum of Chinese higher education institutions. Also, government documents emphasise that these foreign institutions are under Chinese control, meaning China exerts authority over their operations. The local institutions and their foreign partners require accreditation to offer a degree programme, as private institutions are rarely permitted to deliver accredited degree programmes.[20] For instance, the Tsinghua–UC Berkeley Shenzhen Institute for Data Sciences and Information Technology is jointly established by the University of California, Berkeley, and the Tsinghua University under the “support” of the Shenzhen Municipal Government.

Size: Most joint universities are relatively small compared to local institutions. For example, in 2021-22, the Tsinghua–UC Berkeley Shenzhen Institute had approximately 600 students, while Peking University had around 48,600 students. As such, students can expect a more tailored academic experience with a healthy student-faculty ratio. For instance, Duke Kunshan University (a joint venture between Duke University, US, and Wuhan University, China) has a student-faculty ratio of one faculty member for every seven students, while Peking University has roughly one faculty/staff member for every six students; however, when considering only teaching faculty, this ratio at Peking University is higher, indicating a more significant number of students per faculty member.

Location: Sino-foreign cooperative universities are mainly located in large metropolitan areas, such as Shanghai, Beijing, and Nanjing.

Fee: The tuition fees at FHEIs in China, such as the University of Nottingham, Duke Kunshan University, and New York University Shanghai, do not differ much from the home institutions. For instance, in 2022, the annual tuition at Duke University and Duke Kunshan University ranged from US$42,750 to US$60,500. Notably, the tuition fees for most FHEIs are considerably higher than at the local universities. Tuition fees at local Chinese universities vary between US$1,500 to US$3,200, depending on the institution and field of study, with specific programmes like business, medicine, and engineering incurring higher annual fees. For instance, China's top university, Peking University, charges a yearly tuition fee of US$3,340 for international students and US$2,800 for local students, significantly lower than Duke Kunshan University's fees.

United Arab Emirates

When the UAE was formed in 1971, children from rural areas and economically disadvantaged backgrounds had limited access to schooling. However, as the UAE economy has grown and the country has attracted large numbers of expatriates, the education system has focused on developing an educated and skilled workforce to meet the country’s needs.[21] This resulted in significant investments in higher education, including establishing new universities and expanding existing ones.

As the demand for higher education increased, the federal government and individual Emirati rulers developed a system of institutions, including federal institutions, emirate-funded universities, and privately owned foreign institutions.[22] The UAE has modelled its education system on those of the US and the UK. At some level, the uncontrolled expansion of various educational institutions has posed challenges regarding standardisation, quality control, and the diversity of educational systems.[23] Moreover, many institutions established recently have focused on providing inexpensive, job-oriented programmes in areas such as business management, legal and professional training, engineering, and medicine, with a shortage of physical and social sciences programmes.[24]

A notable initiative in the UAE is the establishment of free zones—the Dubai Knowledge Park and Dubai International Academic City (DIAC). At the same time, the country has become a premier destination for foreign universities to establish branch campuses, such as Sorbonne University Abu Dhabi and London Business School Dubai.

The UAE has implemented several policies and programmes to ensure and maintain the quality of foreign institutions.[25] In 2017, the Ministry of Education launched the National Strategy for Higher Education 2030, guided by four pillars: quality, efficiency, innovation, and harmonisation. A comparison of foreign and local universities highlights that the former offers more specialised and exclusive education, with student enrolments concentrated in specific areas. Furthermore, the varying tuition fees among universities suggest that they use different strategies to fund their programmes and attract students from diverse backgrounds. Overall, foreign universities in the UAE represent a strategic approach to achieving excellence in higher education and fostering a knowledge-based economy.

Structure: FHEIs in the UAE must obtain licences from the Commission for Academic Accreditation (CAA), which seeks to ensure the preservation and enforcement of academic standards. Notably, CAA accreditation is not obligatory for several free zones within the UAE. FHEIs operating within the DIAC enjoy many advantages, such as being 100 percent foreign-owned, tax exemptions, and full repatriation of profits.[26] Generally, each emirate in the UAE has its own quality assurance procedures, with the Knowledge and Human Development Authority in Dubai assuming the overall responsibility for quality assurance. Additionally, the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research has issued a list of recognised foreign academic programmes to authenticate students' certificates upon completion of their studies.[27]

Size: FHEIs in UAE have lower student enrolment rates than local universities. For instance, in 2020-21, United Arab Emirates University had over 14,000 students, while New York University Abu Dhabi had 530 students.[28]

Location: FHEIs in the UAE are primarily located in the major urban centres with advanced infrastructure and higher population densities. For example, New York University and Sorbonne University are in Abu Dhabi, while the London Business School has a branch in Dubai. Most foreign universities in the UAE, including Amity University, Heriot-Watt University, University of Wollongong, BITS Pilani, and Hult International Business School, are clustered in economic hubs and centres for international collaboration such as the DIAC. This indicates that the decision to concentrate foreign universities in urban areas in the UAE is a deliberate strategy to prioritise proximity to economic centres and international cooperation.

Fee: FHEIs in the UAE charge higher fees than local universities. For example, the average annual tuition fee at Abu Dhabi University ranges from US$6,000 to US$20,000. Conversely, the cost of completing a 20-month executive MBA at the Dubai branch of the London Business School is US$143,955. This is marginally lower than the cost of the same programme at the same school in London (US$153,293).

South Korea

South Korea’s higher education system has undergone tremendous changes since the mid-20th century amid Western-style modernisation. In 1945, only about 22 percent of adults were literate, while the GER for tertiary education was below 2 percent. As of 2015, the adult literacy rate and GER in South Korea were estimated to be over 99 percent and 93 percent, respectively.[29]

Between 1910 and 1945, Japanese colonisation disrupted the development of higher education in South Korea, intending to assimilate and suppress nationalistic sentiments among Koreans.[30] Under US military administration in the three years following its independence in 1945, South Korea’s higher education sector was developed through US participation in its reconstruction.[31] The country experienced significant economic growth and development in the following years, which led to a surge in the demand for higher education. The 1995 Education Reform Report introduced changes such as an “open education system” and emphasised education based on “autonomy and accountability.”[32] However, the government’s egalitarian principle limited educational choices and, as such, Korean students opted to study abroad, some even starting at the primary school level.[33]

South Korea has continually adopted new education policies to modernise and internationalise its higher education system. In 1999, South Korea launched the Brain Korea 21 (BK 21) programme to enhance higher education by providing funds.[34] In 2004, South Korea launched the Study Korea Project, attracting 50,000 international students by 2010.[35] Furthermore, in 2008, the World-Class University project was introduced to enhance the country’s research capacity and global competitiveness.[36] In 2013, the Ministry of Education and Human Resource Development launched the BK 21 PLUS programme to improve Korean universities’ research capacity. The programme focused on supporting projects that converged different research fields and promoted industry-academia cooperation.

FHEIs in South Korea are governed by the ‘Special Act on Establishment and Management of Foreign Educational Institutions in Free Economic Zones and Jeju Free International City’, along with its Enforcement Decree. The government has implemented reforms aimed at promoting an egalitarian platform for education, enhancing research capacity, and industry-academia cooperation. As in the case of China, foreign universities in South Korea tend to attract only a specific category of students—urban residents who can afford the tuition fees. However, the FHEIs have significant academic freedom. To expand their presence in South Korea, some FHEIs have partnered with local universities and others have opened branch campuses nationwide. For instance, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill has collaborated with Korea University to offer an undergraduate student exchange programme.

Structure: The Ministry of Education is the sole authority. South Korean institutions must adhere to local curriculum regulations, including if offering joint curricula with local or foreign universities, as outlined by a presidential decree. Foreign universities must follow the rules set by the education ministry, including accreditation and local compliance. FHEIs must also conform to the relevant local statutes and ordinances, such as the Higher Education Act and the Foreign Language Education Act. A notable example is the Incheon Global University Campus (IGC), located in the Incheon Free Economic Zone (IFEZ). IGC represents an innovative educational approach where students can earn degrees from prestigious global universities while studying in Korea. Currently, IGC is a collaborative project established by four institutions: the US’s George Mason University, the University of Utah, and the State University of New York (SUNY), and Belgium’s Ghent University. SUNY Korea (located in IGC) is a collaboration between the South Korean government and the SUNY. Stony Brook University confers the degrees obtained at SUNY Korea and maintains oversight over all aspects of the programme, including student admissions and quality assurance in teaching and research.[37]

Size: Local universities have more students enrolled than FHEIs in South Korea. For instance, in 2021-22, Seoul National University had over 28,000 students, while George Mason University, the University of Utah, SUNY, and Ghent University in IGC had around 3,500 enrolments.[38]

Location: FHEIs in South Korea are located in predominantly urban areas. Notably, the IFEZ was established to capitalise on South Korea’s proximity to China and Japan to increase its global appeal.[39] The positioning of FHEIs in urban areas reflects a deliberate decision to prioritise proximity to economic hubs and international collaboration over the geographic distribution of higher education institutions.

Fee: Foreign universities in South Korea charge similar fees as local universities. For example, as per the latest update on the university websites, per semester fees at Seoul National University were approximately US$6,000 and US$6,678 at Ghent University Global Campus. However, it does not account for the annual basic fixed fee of over US$1,500.

Malaysia

The British education model significantly influenced Malaysia’s higher education system, and served as the basis for its development during the colonial era. The system developed in four stages: the inception and development of higher education in Malaysia and Singapore before independence, the establishment of the University of Malaya in Kuala Lumpur in 1961, the establishment and growth of three new national universities and an International Islamic University after 1969, and upgrading agricultural and technical colleges to full university status in 1971-72.[40] Malaysia has developed a dynamic higher education sector that includes public, private, and international institutions.

The Malaysian government has committed to promoting higher education and has introduced various initiatives and laws to improve the sector. One such initiative is the Malaysian Education Blueprint (2015-2025), which aims to raise educational standards to meet international levels.[41] Malaysia launched Education Malaysia Global Services in 2012 to promote the country as a global education destination through international student recruitment and collaborations with foreign universities. These collaborations have brought in foreign investment and contributed to the internationalisation of Malaysia’s higher education sector. FHEIs in Malaysia are governed by the Private Higher Educational Institutions Act 1996 (Act 555). Foreign universities in Malaysia exhibit unique characteristics when compared to local universities.

Structure: By and large, FHEIs in Malaysia operate as branch campuses and award their own degree, diploma, and foundational qualifications identical to that of the host universities. Nevertheless, the recognition of qualifications and programmes at foreign universities is subject to Malaysia’s regulations and accreditation from relevant global professional organisations.

Size: FHEIs in Malaysia have lower student enrolment rates than local universities. For instance, in 2022, Universiti Malaya, located in Kuala Lumpur, had 30,568 enrolled students, while Monash University Malaysia, one of the most prominent foreign university branches, had 9,326 students.

Location: FHEIs are primarily located in or near major urban centres. For instance, Monash University Malaysia is situated in Semenyih, a suburb of Kuala Lumpur, while Xiamen University Malaysia is located in Bandar Sunway, a suburb of Petaling Jaya. Unlike in the UAE, where foreign universities are concentrated in designated academic clusters, FHEIs in Malaysia are spread throughout the country, focusing on major economic hubs. Notably, the Malaysian government and the University of Nottingham established the Crops for the Future Research Centre to provide research support to the Crops for the Future (CFF). Formed in 2009, CFF has collaborated with global organisations to enhance food security, health, and ecosystem sustainability. Backed by the Malaysian government and the University of Nottingham in Malaysia, it integrates research on underutilised crops with the educational platform FutureCrop and offers consultancy services. The initiative is only available at the Malaysia campus as the main campus in the UK is located in an urban area. The centre is an example of the advantages of establishing a branch campus in rural areas.

Fee: Tuition fees at FHEIs in Malaysia are lower than in the home country. For instance, in 2023, Monash University in Australia charges an estimated annual tuition fee of US$33,151.70 for international students and US$22,228.15 for local students studying for an undergraduate degree in accounting, while the university’s Malaysia campus charges international students US$9759.20 and local students US$8,486.26 for local students per year for the same degree programme.

The Roadmap for India

Globally, there are few FHEIs. Most elite universities worldwide have not established branches or campuses in other regions within their countries or abroad. A key reason for this is that transferring the ethos of a university, which is built over the years, across geographies is extremely difficult, and world-class universities are anxious about their reputation.

India’s NEP seeks to promote the Indian knowledge system, and, as such, foreign institutions considering operating in the country will face the challenge of incorporating Indian culture and multilingualism into their higher education curriculum. In the months since the release of the UGC guidelines for FHEIs, only two universities have confirmed their interest in establishing operations in India—Australian institutes Deakin University (which is interested in establishing a campus in Ahmedabad’s GIFT City) and the University of Wollongong.

This limited interest is not entirely surprising. Global experiences (as discussed in this paper) highlight that the structure, size, location, and fees are crucial determinants in the evolution and sustenance of FHEIs and must be carefully examined to reap the benefits of such ‘imports’. As the case studies showcase, FHEIs can engage in more profound research in partnerships with local institutions, while stand-alone FHEI campuses are more teaching-focused. The FHEIs are typically small, highly urbanised, and far more expensive than local universities.

The experiences of China, UAE, South Korea, and Malaysia present clear learnings for India. The structure of the FHEI operating in India will be the most critical aspect. While the draft regulations have not specified a typical structure for the FHEIs, the UGC can consider building a soft, implicit preference for the type of FHEIs it may want to attract. This will depend upon India’s larger goals. If India is seeking to augment its institutions’ research capacity, the UGC should encourage partnership models through which FHEIs establish centres/campuses in collaboration with existing Indian universities. India can also consider the co-location option, where foreign and Indian universities are located within the same campus, thus drawing from each other’s ecosystem and undertaking many collaborative projects. There is significant knowledge spillover in a clustered geographical space.[42] If FHEIs and local universities develop joint centres (in addition to joint teaching and degrees), the research capacity of Indian universities will improve, and this should be a goal of the UGC regulations. Many foreign universities have established ‘centres’ in India, but these typically function as the local hosts for their faculty members who want to conduct research in India, or to reach out to potential Indian students. Nearly all important decisions, including on financing, are made by the home institutions. To boost the capacity of local institutions, the UGC guidelines must encourage research collaborations, where foreign universities also invest in this research.

In addition, the UGC guidelines must encourage a transparent and comparative fee structure, even if unregulated, so that students have all the information when considering applying to the FHEIs. There are significant locational advantages in many Indian cities, and it is unlikely that any FHEI will opt to establish operations in rural areas. At the same time, given the space constraints in India’s urban areas, it is unlikely that the FHEIs based in the cities will be large-sized.

The UGC’s Promotion of Indian Higher Education Abroad initiative, announced in 2005-06 and focused on marketing Indian education programmes abroad and attracting international students, also has some lessons for the current efforts. The initiative showed that despite the prevalence of English, a low-cost delivery system, and technological resources, the Indian education system was not equipped to attract international students. As attracting FHEIs becomes a central policy focus, it must be accompanied by efforts to promote studying in India in foreign countries.

Notably, efforts to internationalise higher education in India must focus on maintaining a balance between the import-export of education to establish the country as a global educational hub rather than focusing exclusively on importing FHEIs. FHEIs in India will not necessarily provide a Western educational experience; instead, they will compete with local institutions, catering only to a limited number of urban students seeking an international degree without relocating or paying high fees. To indeed emerge as a global education hub, India must also push the export of education.

Conclusion

Global experiences with FHEIs do not paint a promising picture for India’s new efforts. Universities, including elite world-class institutions, tend to remain domestic, which explains the low number of FHEIs operating globally.

Given the NEP’s impetus to advance research-based universities, FHEIs operating in India will need to establish a focus on research (in the long term, if not immediately). However, the risk is that the FHEIs may evolve into large centres for India-specific research rather than general research. As such, the UGC guidelines may have limited efficacy, especially if the focus remains on attracting world-class universities. A few universities may certainly open campuses in India, but establishing a substantive presence in terms of research funding is unlikely to happen.

For the guidelines to have real gains—in the form of capacity building of local institutions, developing a large pool of faculty, arresting academic brain drain, offering an equivalent teaching and research experience to students (as in the institute’s home country), and encouraging knowledge spillovers—it is essential to conceive and devise methods that enable establishing collaborative campuses.

Attracting FHEIs will require customised mechanisms that cater to university-specific expectations. One way to do this is to encourage the partner model by empowering local universities to lead in establishing a beneficial partnership. But this will also need additional state support to the local universities to make them attractive partners for FHEIs. A vital reform on this front will be in the governance models of the local universities, where the leadership must be chosen from a pool of global academics who should be given significant autonomy in utilising their research and faculty budgets. This will amplify the research productivity of the institutions and convey a strong signal of quality. The FHEIs need to be seen as drivers of the local economy, and so India can consider establishing educational hubs or clusters. While easing the regulatory burden through the new UGC guidelines is a welcome step, several other institutional incentives will need to be designed to ensure the freedom and autonomy of the FHEIs are not compromised.

Given the high number of foreign university offices in India (primarily clustered in Delhi and Mumbai), it is clear there is an interest in India. To ensure that this interest goes beyond attracting Indian students to foreign countries, it is essential to incentivise the research ecosystem for FHEIs in India. This will be in keeping with the NEP’s goals.

Endnote

[a] Times Higher Education World University Ranking (THE) and QS World University Ranking are major annual global university assessments. THE evaluates teaching and research through 13 indicators. QS emphasises reputation, faculty/student ratio, and research impact.

[1] University Grants Commission, Department of Higher Education, Ministry of Education, Government of India, Draft University Grants Commission (Setting up and Operation of Campuses of Foreign Higher Educational Institutions in India) Regulations, 2023, 2023, https://www.ugc.gov.in/pdfnews/9214094_Draft-Setting-up-and-Operation-of-Campuses-of-Foreign-Higher-Educational-Institutions-in-India-Regulations-2023.pdf.

[2] Sreeradha Basu and Rica Bhattacharyya, “As Record Number of Indians Head out, Studying Abroad Is Easy, Landing a Job Not so Much,” The Economic Times, February 11, 2023, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/nri/work/studying-abroadis-easy-landing-a-job-not-so-much/articleshow/97812363.cms?from=mdr.

[3] Anna Valero and John Van Reenen, “The Economic Impact of Universities: Evidence from across the Globe,” Economics of Education Review 68 (February 2019): 53–67, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2018.09.001.

[4] Bradley Beecher and Bernhard Streitwieser, “A Risk Management Approach for the Internationalization of Higher Education,” Journal of the Knowledge Economy 10, no. 4 (2017): 1404–26, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-017-0468-y.

[5] Richard Garrett, “International Branch Campuses—Curiosity or Important Trend?” International Higher Education, no. 90 (June 6, 2017): 7–8, https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2017.90.9994.

[6] Cross-Border Education Research Team, “C-BERT International Campus Listing,” C-BERT, March 2023, https://www.cbert.org/intl-campus.

[7] Yovana Soobrayen Veerasamy, “Emerging Direction of U.S. National Higher Education Internationalization Policy Efforts between 2000 and 2019,” Journal of Comparative & International Higher Education 13, no. 4 (2021): 4–15, https://doi.org/10.32674/jcihe.v13i4.2426.

[8] María Escriva Beltran, Javier Muñoz De Prat, and Cristina Villó, “Insights into International Branch Campuses: Mapping Trends through a Systematic Review,” Journal of Business Research 101 (2019): 507–15, https://doi.org/-10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.12.049.

[9] Cross-Border Education Research Team, “C-BERT International Campus Listing”

[10] Kai Yu, Andrea Lynn Stith, Li Liu, and Huizhong Chen, Tertiary Education at a Glance: China (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 2012).

[11] Yu, Stith, Liu, and Chens, Tertiary Education at a Glance: China

[12] Bin Wu and Yongnian Zheng, “Expansion of Higher Education in China: Challenges and Implications,” Briefing Series, no. 36 (February 2008): 1–13, https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/iaps/documents/cpi/briefings/briefing-36-china-higher-education-expansion.pdf.

[13] Christine T. Ennew and Yang Fujia, “Foreign Universities in China: A Case Study,” European Journal of Education 44, no. 1 (2009): 21–36, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3435.2008.01368.x

[14] Shujie Yao et al., “The Impact of Higher Education Expansion on Social Justice in China: A Spatial and Inter-Temporal Analysis,” Journal of Contemporary China 19, no. 67 (2010): 837–54, https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2010.508586.

[15] Ennew and Fujia, “Foreign Universities in China: A Case Study”

[16] Yao et al., “The Impact of Higher Education Expansion on Social Justice in China”

[17] Ka Ho Mok, “Education Market with the Chinese Characteristics: The Rise Education Market with the Chinese Characteristics: The Rise of Minban and Transnational Higher Education in China Minban and Transnational Higher Education in China,” Higher Education Quarterly 75, no. 3 (2021): 398–417, https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12323.

[18] Futao Huang, “Internationalization of Higher Education in the Developing and Emerging Countries: A Focus on Transnational Higher Education in Asia,” Journal of Studies in International Education 11, no. 3–4 (2007): 421–32, https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315307303919.

[19] Ennew and Fujia, “Foreign Universities in China: A Case Study”

[20] Huang, “Internationalization of Higher Education in the Developing and Emerging Countries”

[21] Daniel Kirk and Diane Napier, “The Transformation of Higher Education in the United Arab Emirates: Issues, Implications, and Intercultural Dimensions*,” in Nation-Building, Identity and Citizenship Education, ed. Holger Daun and Joseph Zajda (Dordrecht: Springer, 2009): 131–42, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-9318-0_10.

[22] Kirk and Napier, “The Transformation of Higher Education in the United Arab Emirates”

[23] Amitabh Upadhya, “Higher Education - Challenges and Opportunities in the Middle East,” Higher Education Digest, October 14, 2020, https://www.highereducationdigest.com/higher-education-challenges-and-opportunities-in-the-middle-east/.

[24] Upadhya, “Higher Education - Challenges and Opportunities in the Middle East”.

[25] Commission for Academic Accreditation, Ministry of Education, United Arab Emirates, Standards for Institutional Licensure and Program Accreditation, 2019, https://www.caa.ae/PORTALGUIDELINES/Standards%202019%20-%20Dec%202019%20v2.docx.pdf.

[26] Stephen Wilkins, “Who Benefits from Foreign Universities in the Arab Gulf States?” Australian Universities’ Review 53, no. 1 (2011): 73–83, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ926453.pdf

[27] United Arab Emirates, Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research (MOHESR), Ministry of Education, https://www.moe.gov.ae/En/MediaCenter/archive/mohesr/news/Pages/MOHESR-announces-list-of-accredited-programs-and-urges-students-to-consult-with-it-before-joining-licensed-universities-and.aspx#:~:text=Bachelor%20Of%20Arts%20In%20English%20Language%20(Translation%2C%20Literature%2C%20Teaching,Biotechnology)%20%2F%20Bachelor%20Of%20Science%20In.

[28] NYU Abu Dhabi, https://nyuad.nyu.edu/en/news/latest-news/community-life/2021/november/530-students-from-over-85-countries-join-nyuad-as-the-class-of-2025.html#:~:text=NYU%20Abu%20Dhabi%20(NYUAD)%20this,seven%20Emirates%20in%20the%20UAE.

[29] Deepti Mani, “Education in South Korea,” WENR: World Education News + Reviews, October 16, 2016, https://wenr.wes.org/2018/10/education-in-south-korea.

[30] Jeong-Kyu Lee, “Japanese Higher Education Policy in Korea (1910—1945),” Education Policy Analysis Archives 10 (March 7, 2002): 14 https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v10n14.2002.

[31] Sungho Lee, “The Emergence of the Modern University in Korea,” Higher Education 18, no. 1 (1989): 87–116, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-2563-2_10.

[32] Kiyong Byun and Minjung Kim, “Shifting Patterns of the Government’s Policies for the Internationalization of Korean Higher Education,” Journal of Studies in International Education 15, no. 5 (2010): 467–86, https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315310375307.

[33] Mugyeong Moon and Ki Seok Kim, “A Case of Korean Higher Education Reform: The Brain Korea 21 Project,” Asia Pacific Education Review 2, no. 2 (June 2001): 96–105.

[34] Terri Kim, “Higher Education Reforms in South Korea: Public—Private Problems in Internationalising and Incorporating Universities,” Policy Futures in Education 6, no. 5 (2008): 558–68.

[35]Ahn Byong-man, “Study Korea Emerges as New National Brand,” The Korea Times, July 21, 2010.

[36] Htin Shar, Higher Education Development of Korea: WORLD CLASS UNIVERSITY PROJECT 2008 to 2012, February 2017.

[37] Imin Kao, Yacov Shamash, and Choon Ho Kim, “Establishing an American Global Campus in SUNY Korea: Challenges and Excitement in Preparing Global Engineers,” 2013 ASEE International Forum, June 22, 2013, 21–23.

[38] Seoul National University, “Facts - Overview - About SNU,” April 2022.

[39] Julia Yoo, “Educating the World in the Incheon Free Economic Zone,” Korea IT Times, August 18, 2016.

[40] Viswanathan Selvaratnam, “Malaysia’s Higher Education and Quest for Developed Nation Status by 2020,” Southeast Asian Affairs 2016, July 2016, 199–222.

[41] Ministry of Education, Government of Malaysia, Malaysia Education Blue Print 2013 – 2025, 2013.

[42] Roderik Ponds, Frank van Oort, and Koen Frenken. "Innovation, spillovers and university–industry collaboration: an extended knowledge production function approach." Journal of Economic Geography 10, no. 2 (2009): 231-255.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV