The Shaping of a Sustainable India

Today’s India is bold and ambitious, seeing eye-to-eye with the Global North. It is a nation that has big dreams and works hard to achieve those dreams. This volume is a tribute to the India that has traversed a long way over the last 75 years and aspires to reach even greater milestones. It is also a tribute to the millennial India that understands its priorities for the next 25 years and is gearing up to face and overcome its challenges.

Azadi Ka Amrit Mahotsav is the government’s initiative to celebrate and commemorate 75 years of India’s independence and the glorious history of its people, cultures, and achievements. Yet, it is not merely a celebration of the India of yore, but of the aspirational and ambitious India of the present and future. It is in this context that this compendium discusses the 10 policies that will shape the future sustainable India. During the 2021 Independence Day celebration, Prime Minister Narendra Modi used the term Amrit Kaal to delineate India’s development pathway over the next 25 years. “The fulfilment of our resolutions in this Amrit period will take us to the hundredth anniversary of Indian independence with pride,” he stated.[1] This compendium, Amrit Mahotsav: 10 Policies Shaping a Sustainable India, aims to celebrate the 75 years of Indian independence (the Amrit Mahotsav) and is a tribute to the India that will traverse the next 25 years of its development armed with crucial policies that will address enduring challenges and shape a more sustainable future for the country and its people.

The last few years have witnessed changes in developmental governance in the country through some key policy interventions. These interventions are largely embedded in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that are today regarded as the bedrock of not just global developmental governance, but governance at all levels. The articles in this volume proceed on the hypothesis that the Indian aspiration to grow as a US$5-trillion economy needs to be based on strong fundamentals that are being created through policies that strengthen the country’s human and physical capital.

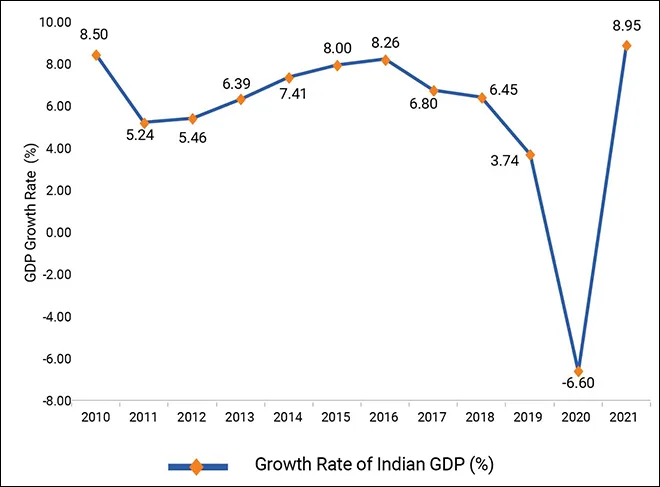

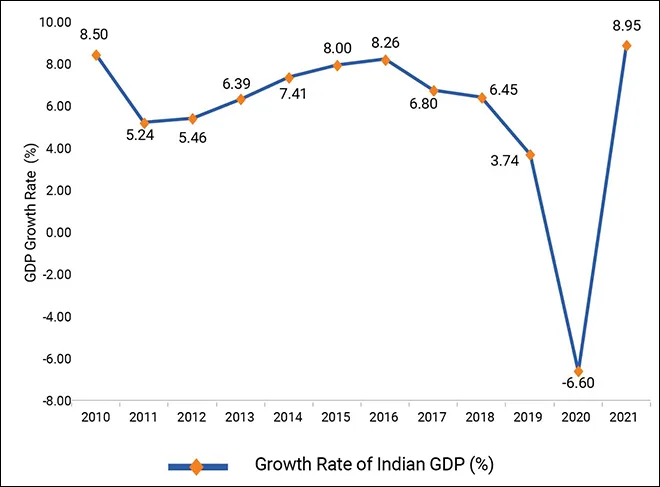

Even as the goal of emerging as a US$5-trillion economy by 2024-25 received a blow due to the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic, the economic revival remains palpable in terms of GDP growth (see Figure 1). While GDP declined from US$2.68 trillion in 2019 to US$2.51 trillion in 2020, it revived to US$2.73 trillion in 2021. Indeed, the Indian economy has immense potential to touch the coveted US$5 trillion figure by FY 2026-27, and US$10 trillion by FY 2033-34.[2]

Figure 1: India's GDP Growth Rates (2010 to 2021)

Source:Computed by author from World Bank database[3]

At the same time, “GDP is the worst measure of economic activities but for all others. …. Because everything else you take (sic) comes with their own limitations and serious subjectivity”.[4] This statement by India’s chief economic advisor is partially true and contestable from a normative perspective. It is a fact that GDP is an objective measure of economic activity, but treating GDP as an omnipotent measure, especially of economic well-being, is possibly the gravest flaw. What has often not been acknowledged in this ‘growth game’ is the ‘cost of growth’.

The Indian Growth Story and Development Paradox

India has historically presented itself as a developmental paradox—“ample resource, ample poverty”, which some would refer to as a manifestation of the so-called “resource curse”.[5] The resource curse hypothesis is posited as the phenomenon of economies with abundant natural resources still exhibiting “development deficit”, i.e. low incomes, low economic growth, weaker democracy, and worse performance in developmental indicators than economies with less bountiful natural resources. But the Indian condition is much more complex than can be explicated by such a linear theoretical construct. Throughout India’s history, there have been regions of underdevelopment, and of growth,[6] located in an almost linear and contiguous fashion.

At the same time, it needs to be understood that unbridled and blind pursuit of economic growth without any consideration of the concerns of distributive justice or equity and sustainability of the natural ecosystem brings about an organic corollary in the form of “costs of growth”. They are often not easily perceptible in the short run, but become visible in the long run. These may be in the form of losses to livelihoods and problems of rehabilitation due to creation of physical infrastructure, or losses in ecosystem services affecting human habitat.[7]

The Indian development story since independence, and especially after economic liberalisation in the early 1990s, falls in this classification. Economic growth entailed the creation of new capital through large capital expenditures. In many cases, the long-run costs that society must bear due to losses in livelihoods and ecosystem services are more overwhelming than the economic benefits—the negative benefit-cost difference reached through a more comprehensive analysis conducted for a longer run therefore raises questions on the efficacy of such investments.[8] Thus, whereas large-scale land-use changes for linear infrastructure, agriculture, industry, and urban settlements, and alterations of hydrological regimes through structural interventions over natural flows were implemented for economic progress, these have also been associated with social costs of rehabilitation or lack of rehabilitation leading to conflicts. Yet, there is no denying the critical role of physical capital in promoting economic growth, even as there is ample empirical evidence of physical infrastructure enhancing the overall business environment and economic competitiveness at the macro-scale.[9] In that sense, this was a necessary evil that the Indian socioeconomy had to endure, especially during the initial stages of its post-independence development.

The Changing Vision of Economic Progress

The measure of growth as the sole parameter of development or economic progress has been challenged globally for decades. The development thinking that prevailed in the post-war decades of European reconstruction and decolonisation of what was then called the ‘third world’, which concentrated on growth through capital formation, was challenged and the human face in development paradigm became prominent.[10] Over time, the Club of Rome’s doomsday thesis revisited the Malthusian creed that depleting natural resources due to anthropogenic interventions will not be able to sustain human economic growth ambitions for the future.[11]

There have been many conventions, scientific assessments, and global declarations that sought to promote a more holistic approach to development, including the Millennium Development Goals that would eventually be replaced by the more comprehensive agenda created by the SDGs in 2015. While presenting a substantially extended and comprehensive agenda for developmental governance through 17 goals, the SDGs find a theoretical underpinning in economist Mohan Munasinghe’s ‘sustainomics’ that is framed by a transdisciplinary knowledge base. This construct combines economic, social, and environmental goals, thereby addressing the three normative objectives of equity, efficiency, and sustainability.[12] These objectives, in many cases, emerge as irreconcilable.

India’s development trajectory has traditionally not been in consonance with this thinking. This thinking is changing, however. The government attempted to provide vulnerable populations with social security during the pandemic-induced lockdown, yet large sections were left behind despite the government’s best efforts. This is due to an enduring institutional problem with the distribution element emerging from the size of the population related to the unregistered informal sector and the large migrant labour force that remains to be identified in government records. It is apparent that it is the market forces that have so far provided the social nets to the poor and vulnerable. The lockdown was tantamount to a locking down of the organic market forces, thereby leaving the informal labour force in the lurch. The SDGs therefore present a governance challenge for the Indian development policy machinery.

The Synergy Between SDGs and Inclusive Wealth

The SDG agenda rests largely on the four forces of capital—human capital (SDGs 1-5), physical capital (SDGs 8 and 9), natural capital (SDGs 14 and 15), and social capital (SDGs 10 and 16). The United Nations Environment Programme’s report, Inclusive Wealth, discusses the changes in the social values of three of these capital assets, namely, natural, human, and produced or physical capital between 1990 and 2014. As per this report, between 1990 and 2014, although the “inclusive wealth” of India increased by 1.6 percent per annum driven by growth in human and physical capital, there was a decline in per capita inclusive wealth from US$368 in 1990 to US$359 in 2014 (both at 2005 prices). If inclusive wealth is taken as the factor or fudamental basis for development, then such a decline raises serious questions on the sustainability of the development process. However, post-2014, there have been significant policy interventions on various human and physical capital domains that have helped push India’s development agenda. These policies are presented in this compendium.

At the same time, academics in the West and their supporters in the Global South have often advocated for ‘degrowth’ as the solution to the world’s woes. The degrowth thesis promotes negative growth and a retreat from the current ways of living. This entails contraction of economic activities in the Global North and emancipation from the dominant reductionist paradigm of growth fetishism.

Degrowth—while discussing the extensive damage that growth has and will cause to the ecosystem—underlines the decoupling of human well-being and GDP per capita. For example, wealthier economies like the United States (US) have worse distribution systems than countries that have lower incomes per capita like Spain, and the latter also has better healthcare systems. Prevailing levels of well-being can be maintained in Finland even with 10 percent of their current GDP, with only better equity principles and practices entailing redistribution.[13] The process of contraction in economic activities in the Global North by viewing development from an ‘anti-growth’ perspective is posited to create the space for a more self-defined pathway for social organisation in the Global South.

However, India’s development cannot be in the direction of degrowth. ‘Degrowth’ is a clarion call that is emanating from a world that not only has already grown, but that is more equal in economic terms (income or wealth equality parameters), more equitable from the perspective of distributive justice, and where social security has helped evolve a welfare state. India is yet to reach that stage. While equity and distribution concerns still pose a challenge in this 1.3-billion-plus world, a recent analysis argues how increasing income and wealth inequalities can inhibit the long-term growth prospects of India, especially when consumption demand is the main driver of growth.[14] The recent example of Sri Lanka’s sudden shift to organic farming and its consequent deleterious impacts on the country’s food security is a case in point: the ideals of degrowth cannot be imposed nor can an economy be hurled into a paradigm for which it is not prepared.

About this Volume: The Indian Priorities

Over the last eight years, significant policy interventions have gone into the development space, especially for improving the country’s physical and human capital. The pandemic acted as a shock to the global economic and development domains and has affected the path to achieve the SDGs. There is no doubt that the Indian dream of achieving US$5 trillion and US$10 trillion in growth needs to be based on strong fundamentals that are enabled by the SDGs.

This volume presents 10 selected policy interventions among many that are poised to shape a sustainable India. These are the following:

- POSHAN Abhiyan, which strives to minimise the level of stunting, undernutrition, anaemia, and low birth weight babies. In this chapter, Shoba Suri outlines the significance of the programme, its achievements so far, and its imperatives in the form of a plot structured, time-bound and location-specific strategies with due consideration to the consequences of socioeconomic factors and the impact of the pandemic.

- Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana, which entails the world’s largest health assurance scheme, with the objective of providing a health cover of INR 5 lakh per family per year for the poor and vulnerable households. Oommen C Kurian discusses the programme and uses a small case study on its beneficial impact and how such a scheme is a replicable model for many other parts of the world.

- Jal Jeevan Mission, which aims to provide access to safe and adequate drinking water by 2024 to all households. Sayanangshu Modak draws the connection and causal relationship of this mission to various health and productivity-related outcomes, and discusses how it will have an impact on the overall progress of the nation.

- Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan, which presents an overarching and comprehensive programme for the school education sector with the broader goal of improving school effectiveness, measured in terms of equal opportunities for schooling and equitable learning outcomes.[15] Malancha Chakrabarty, while describing the broad contours of the programme, argues how it helps facilitate the achievement of the human capital-related SDGs. She underlines its resonance with the thinking of Indian intellectuals.

- National Skill Development Mission, which is driven by the objective of bridging the necessary ‘skill gap’ in the Indian economy. Sunaina Kumar, while introducing the wide chasm between the demand and supply of skilled human capital to address the gap between Indian economic ambition and achievement, highlights the significance of the programme. She outlines what needs to be done to make this programme more effective for building a sustainable India.

- Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee, which aims to enhance livelihood security in rural areas by providing at least 100 days of wage employment in a financial year to at least one member of every household whose adult members volunteer to do manual work. Soumya Bhowmick examines how this has offered a cushion to vulnerable communities during times of crisis, including the pandemic. He reiterates how it helps address the SDGs related to poverty alleviation and food security.

- National Smart Cities Mission, which is an urban renewal and retrofitting programme with the objective to develop smart cities across the country, making them citizen-friendly and sustainable. Aparna Roy evaluates how the mission can help urban centres emerge as hubs of future regional development and economic growth and be resilient to the shocks of climate change.

- Prime Minister Gati Shakti Mission entails a revolutionary approach to transform mobility keeping in mind economic growth and sustainable development. Launched in October 2021, the mission aims to provide multimodal connectivity infrastructure to various economic zones. Debosmita Sarkar describes how this mission can help address the connectivity conundrum across the country and its potential to emerge as a game-changer in the connectivity domain and help achieve economic growth.

- Swachh Bharat Abhiyan is a significant cleanliness campaign which aims to eliminate open defecation and improve solid waste management. Mona discusses the world’s largest sanitation campaign and highlights its achievements.

- Aadhaar, the world’s largest biometric system, is another success story. With almost every Indian adult being an Aadhaar holder and a carrier of unique and secure identity, the movement has fostered social, economic, and technological inclusion on a national scale. This is what Anirban Sarma and Basu Chandola emphasise in their chapter. The authors use Aadhaar as a case study of the role of information and communication technologies in bringing about social and economic progress. They underline its replicability for many parts of the world when governments are trying hard to address concerns of equity and distributive justice.

The 10 chosen policies address critical elements in inclusive wealth, namely, human and natural capital. As inequality can dampen economic growth,[16] future growth should be spurred by a more equitable and sustainable world driven by the SDGs. India’s progress, therefore, must rest on two key elements: a simultaneous growth in health- and education-induced human and physical capital, without compromising on the sustainability of natural capital; and a more equal India serving the cause of distributive justice through reduced inequality.

This introductory piece is a revised and extended version of the article, “Towards a 10-trillion-Dollar Indian Economy Based on the SDG Agenda”, written by the author as part of ORF’s series, India@75: Aspirations, Ambitions, and Approaches.

[1] Prime Minister’s Office, “The Prime Minister, Shri Narendra Modi addressed the nation from the ramparts of the Red Fort on the 75th Independence Day,” August 15, 2021.

[2] “India would become $5-trillion economy by 2026-27: CEA V Anantha Nageswaran”, Economic Times, June 14, 2022.

[3] World Bank, “GDP growth (annual %) – India,” World Bank Group.

[4] “India would become $5-trillion economy by 2026-27”

[5] Behera Bhagirath and Pulak Mishra, “Natural Resource Abundance in the Indian States: Curse or Boon?”, Review of Development and Change. 17(1) (2019):53-73. doi:10.1177/0972266120120104

[6] Jayanta Bandyopadhyay and Nilanjan Ghosh, ““Holistic Engineering and Hydro-diplomacy in the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna Basin”, Economic and Political Weekly, 44 (45) (2009): 50-60.

[7] Rodney van der Ree, Daniel J. Smith, and Clara Grilo, “The Ecological Effects of Linear Infrastructure and Traffic: Challenges and Opportunities of Rapid Global Growth”, in Handbook of Road Ecology, ed. Rodney van der Ree, Daniel J. Smith and Clara Grilo (New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015).

[8] Nilanjan Ghosh, “Promoting a GDP of the Poor‟: The imperative of integrating ecosystems valuation in development policy”, Occasional Paper No. 239, March 2020, Observer Research Foundation.

[9] T. Palei, “Assessing the impact of infrastructure on economic growth and global competitiveness”, Procedia Economics and Finance (2014): 1-8.

[10] Nilanjan Ghosh, “(2017): “Ecological Economics: Sustainability, Markets, and Global Change”, in Mukhopadhyay, P., et al (eds.) Global Change, Ecosystems, Sustainability. (New Delhi: Sage).

[11] Dennis Meadows, Donella Meadows, Jørgen Randers, and Willian Behrens III (Eds), A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind. New York: Universe Books, 1972.

[12] Mohan Munasinghe, “Addressing Sustainable Development and Climate Change Together Using Sustainomics.” WIRES Climate Change 2(1) (2010): 7–18.

[13] Jason Hickel, Less Is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World (New York: Penguin Random House, 2020)

[14] Nilanjan Ghosh, “Is increasing wealth inequality coming in the way of economic growth in India?”.

[15] Department of School Education & Literacy, Ministry of Education, Government of India, “About Samagra Shiksha”.

[16] Nilanjan Ghosh, “Is increasing wealth inequality coming in the way of economic growth in India?”.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV