-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The preference for motorised mobility at the policy level is driven by the assumption that an increase in motorised mobility would necessarily lead to access to opportunity and overall growth

This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

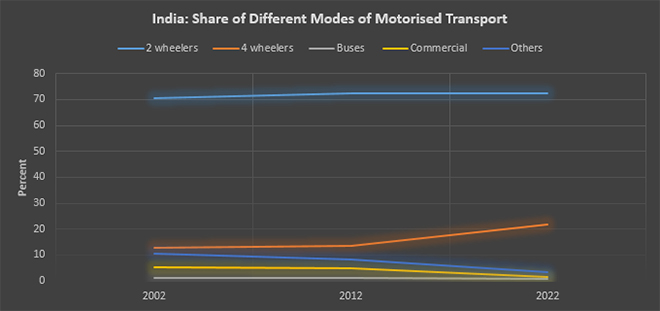

Though motorised mobility in India is predominantly ‘two wheeled’, mobility itself is ‘two legged’ as the predominant mode of transportation remains ‘walking’. Out of the registered vehicle stock of over 352 million in September 2023, over 73 percent were two-wheelers. Excluding two and three-wheelers, there were about 58 vehicles per 1,000 people in India in 2023. This is a fourfold increase from 2012 but it is still much lower than that in many developed countries where the number exceeds 800. Roughly half the Indian population is estimated to walk or use a bicycle to work in India. These commuters face innumerable hazards on the road partly because Indian roads are vehicle-centric and partly because the driving culture is anti-pedestrian and anti-cyclist. The preference for motorised mobility (even if electric) at the policy level is driven by the assumption that an increase in per-person availability of motorised mobility would necessarily lead to access to opportunity and overall growth.

Transportation or mobility is typically a means to an end in both passenger and freight aspects but often public policy tends to treat mobility as an end in itself or as a substitute for access. For example, low per-person consumption of transport in India compared to developed economies is framed as one of India’s key development problems (as it is in the case of consumption of other developmental goods such as energy). The obvious policy response has been to build roads, multilane highways, metropolitan, and national rail networks, airports and ports to increase the availability of motorised mobility. In addition, public policy also promotes the ownership of private vehicles through explicit and implicit subsidies even though it is well known that motorised private transport thrives on the externalisation of its true costs such as energy price, pollution, and congestion.

Transportation or mobility is typically a means to an end in both passenger and freight aspects but often public policy tends to treat mobility as an end in itself or as a substitute for access.

Given that people do not necessarily need mobility, but rather a level of accessibility which enhances the degree to which they can participate in spatially unconnected activities such as jobs, shopping, and schooling, the rate of growth of personal motorised mobility in India suggests a mismatch in demand and supply of access to opportunity such as spatial disequilibrium in the job market along with the inadequacy of public transport options.

Mobility in urban areas in India is in general a solution to problems of spatial disequilibrium in the labour market, expressed by misdistribution of labour in relation to employment opportunities. Like migration, external commuting is a means of restoring spatial equilibrium between available employment and the resident workforce. Unlike migration, it is also a means of capitalizing upon private and community investment in areas that lack ‘development’. The satellite townships that have developed in the last two decades around large cities in India are testimony to this proposition. External commuting from these satellite townships is heavily dependent upon the availability of residual assets at relatively low prices to compensate for the burden of long daily work trips into key business districts of the city.

Although very little external commuting is in long-term equilibrium, it does not follow that external commuting is a transient phenomenon of only passing interest. It will continue to be an important means of adjustment to spatial anomalies in job opportunities, and its importance may well increase as economic changes accelerate and the daily travel range increases. External commuting has eased the problems of employment dislocation by transferring the redeployment burden to the commuter, whose daily journey has linked the undeveloped areas in the periphery of a large city and the more prosperous workplaces located in key business districts and transferred a substantial share of this prosperity back to the satellite townships which were until very recently agricultural or wastelands.

The satellite townships that have developed in the last two decades around large cities in India are testimony to this proposition.

The development of satellite townships, a process of ‘suburbanisation’ is the result of the market taking charge in the absence of interventions on the part of the government in the form of systematic spatial planning. The potential contribution of spatial planning to the reduction of motorised mobility and the consequent impacts on the environment has been substantiated by many empirical studies which have concluded that about one-third of the variation in per person transport energy consumption is attributable to land use characteristics.

Studies based on data from industrialized countries have established that land use characteristics explain up to 27 percent of the variation in travel distances per person although half of the variation in travel distance per person could be explained by socioeconomic factors. Features of compact land development on the urban fringe, such as high density, a high level of jobs-housing balance and compact physical pattern, have been shown to enhance people’s accessibility to facilities and services and these have also been found to reduce the overall need for travel and the distance and duration of motorized journeys. A study conducted using housing survey data in the Netherlands showed that the density of urban form has a significant impact on mobility (commuting distance and mode choice) and thus on CO2 emissions. It found that workers living in the highest density locations (more than 25 houses per hectare) tend to travel about 11.9 km (kilometres) less than workers in the least dense location. In more densely populated areas workers tend to change from car to other travel modes, notably public transport (metro and tram). Accordingly, the predicted CO2 emissions per passenger were lower in the highest-density areas. When a worker migrated from the lowest to the highest urban density level, the CO2 emissions per passenger were reduced by 47 percent. An increase in net population density of 10 persons per hectare was found to reduce 0.764 minutes in commuting time.

The cities with the highest densities were those with low car usage and high levels of provision of public transport.

A study which measured petroleum consumption and population densities in a range of large cities around the world found a clear negative relationship between the two: as densities rise, fuel consumption falls dramatically. The US cities had consumption rates twice as high as those in Australian cities and four times as high as those in European cities. The cities with the highest densities were those with low car usage and high levels of provision of public transport. The obvious conclusion from this study is the need for stronger policies of urban containment and investment in mass transport systems.

In the context of cities in developing countries, the form of land use is often believed to have a major influence on commuting patterns although empirical research is scarce. In Asian megacities such as New Delhi, Mumbai, Shanghai, Kuala Lumpur, Jakarta and Manila there has been a dramatic increase in urban sprawl on the city fringe which has led to longer commuting distances and greater traffic congestion in the central city area. Longer travel demand and greater car usage in Asian megacities are seen to have been caused by new forms of land development at the neighbourhood level, that is, the non-pedestrian/cyclist-friendly urban form which emerged after the 1990s.

Although the concept of compact urban cities has been very influential, it has generated considerable criticism on a mixture of ideological and technical grounds. Ideologically, reliance on public intervention is questioned by many studies. These studies essentially argue that the market will resolve the issue as it has in Australia and the United States where commuting distances and times have tended to fall in recent years because of employment decentralization and hence increased suburb-to-suburb work trips, and where the major growth in travel arises from non-work trips. The key argument is that ‘polycentric cities’, through market pressure, are the most effective way of dealing with the transport energy consumption and pollution problem. It is feared that the advocacy of dispersal may become a self-fulfilling prophesy and contribute to the evolution of future urban forms that are increasingly inefficient and socially inequitable. There is also scepticism over the realistic prospects for massive investment in public transport.

The key argument is that ‘polycentric cities’, through market pressure, are the most effective way of dealing with the transport energy consumption and pollution problem.

For some years, geographers have been disputing the nature of these human and job movements. Some argue that growth has been occurring as a result of continuing suburbanisation which is sometimes discontinuous—where development is hindered by green belts, for example. Others argue that the process has been one of ‘counter-urbanization’. This view suggests that growth has been focused, not on the periphery of existing urban areas but in the least urban areas. Thus, households and companies have been consciously relocating to small towns in a distinct anti-urban movement.

Motorised transport thrives on externalisation of its true costs such as energy price, pollution (noise & atmospheric) and congestion. Motorised transport receives a substantial implicit subsidy in the form of access to publicly owned spaces at almost no cost. In India, private motorized transport vehicles can be parked in public places including pavements meant for pedestrians, at little or no cost. This is true even in areas where the real estate value is among the highest in the World. A level playing field for rickshaws, cycles, pedestrians and motorized vehicles should index parking charges to real estate values and take into account the area occupied when parked. It should also price congestion (including grid congestion by electric vehicles), pollution and other externalities.

Motorised transport receives a substantial implicit subsidy in the form of access to publicly owned spaces at almost no cost.

The romanticisation of electric mobility is now replacing the romanticisation of mobility. There is a need for deeper thinking on mobility for better outcomes. From the perspective of transport systems behaviour, there is no need for ‘growth in mobility’ if mobility is defined in terms of its purpose. Purposeful mobility measured in terms of the number of trips that have to be made by a person per day to meet particular needs is more or less a constant. Purposeful mobility needs to increase only when the number of people in a given area increases. Second, freedom of choice in mobility does not increase when the number of modes of transport is increased. Freedom of choice is a question of economics. Those who cannot afford certain modes of transport do not have freedom of choice.

Third, in any transport system, an increase in speed does not necessarily save time. To understand why, we need to see each ‘trip’ in terms of its origin and destination. History has shown that an increase in speed moved either the origin (e.g., home) or the destination (e.g., work place) with time for travel remaining the same. In other words, speed changed physical structures rather than changing travel time. In the decade after the Second World War, the advantage of the motorised transport user over the pedestrian in the industrialised world was his speed in operating in an environment primarily designed to the pace of the pedestrian. By the 1970s, the relative advantage of the motorised transport user over the pedestrian shifted to his distance advantage in an environment designed for the automobile. In that environment, the absolute advantage of motorised transport declined as activities spaced themselves in keeping with the dominant capabilities of motorised transport.

Lydia Powell is a Distinguished Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation.

Akhilesh Sati is a Program Manager at the Observer Research Foundation.

Vinod Kumar Tomar is a Assistant Manager at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Ms Powell has been with the ORF Centre for Resources Management for over eight years working on policy issues in Energy and Climate Change. Her ...

Read More +

Akhilesh Sati is a Programme Manager working under ORFs Energy Initiative for more than fifteen years. With Statistics as academic background his core area of ...

Read More +

Vinod Kumar, Assistant Manager, Energy and Climate Change Content Development of the Energy News Monitor Energy and Climate Change. Member of the Energy News Monitor production ...

Read More +