As a member of the United Nations and a signatory of the Sustainable Development Goals, India’s participation in global ambitions to eradicate the global community’s social and economic ills is necessary. As the second largest population in the world, of which a large population still suffers from these ills, India’s ability and subsequently its actions in reducing these threats to its society will be crucial in making or breaking these global goals. Though specific efforts, initiatives and programmes by subsequent governments will determine India’s proactivity to achieving the global goals, data collection, evaluation and presentation will be the key in determining the effectiveness as well as the pitfalls of these actions. Without quality data and impartial and transparent monitoring and evaluation programs, India’s endeavours run the risk of falling short or simply not reaching their true potential.

India continues to struggle with quality data collection, evaluation and presentation. Stuck with the remnants of a pre-digital era, government’s data collection system still heavily relies on manual inputs and hand recording rather than using digital tools. New programs like Digital India and concerted efforts by previous governments to begin the process of data digitisation are helping bring India to a globally acceptable standard, large data points especially as the rural level are still collected using archaic tools and methods. This not only makes programmes and initiatives harder to appraise and audit but renders monitoring and evaluation relatively ineffective.

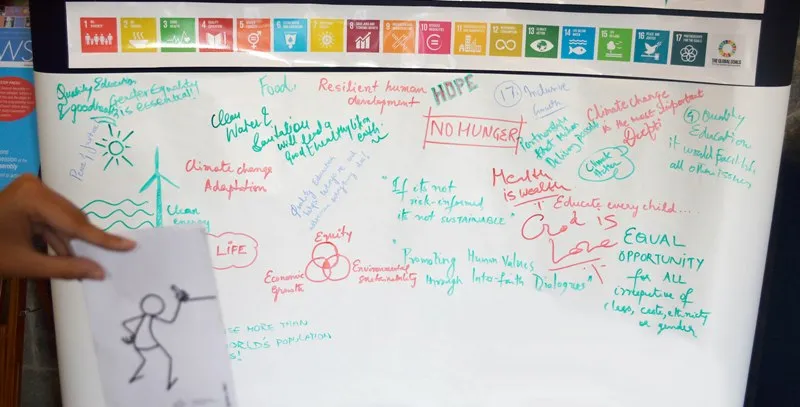

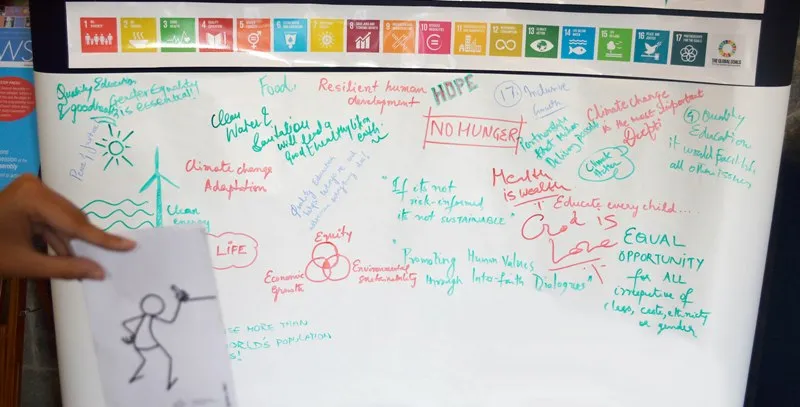

This is relatively important given India’s acceptance of the Sustainable Development Goals that it, with the world, hope to achieve by 2030. It is furthermore crucially important for the goals set towards elimination of hunger and malnutrition. Periodic data collection and hence, timely monitoring and evaluation is paramount in creation of new responses or transforming old policies. It has the potential to identify outcomes of interventions and present new avenue of improving efficiency, effectiveness and inclusivity of programmes aimed at accomplishing Goal #2 of the 17 SDGs.

Though this is the first time that hunger and nutrition have been separated as a global goal in themselves, India has been fighting these societal negatives for many years. Despite large food programmes, agriculture initiatives and social programmes, India’s fight with hunger and malnutrition remains dogged by inefficiencies, lack of resources and sparse information. As of today, India still hosts a quarter of the world’s undernourished people, one-third of the world’s malnourished children and one-third of the world’s food insecure people. India ranks 55th out of 76 countries on the Global Hunger Index and 73 percent of Indian households do not have sufficient access to food or health.

The Indian government is currently aligning its policies to the SDGs in hopes to become more efficient in dealing with both hunger and nutritional issues. But while it creates new policies and tinkers with existing strategies, India must also keenly focus on strengthening its data collection on these two indicators and their many sub-indicators. This is key as data is able to depict the prevailing situation in the country and help in drawing out trends, patterns and necessary pieces of information that assist in corrective policy measures.

Health and nutrition scholars may argue that India does have a few programmes already initiated to capture data relating to hunger and nutrition. While they will not be wrong in quoting surveys like the NFHS, NNMB, DLHS, HUNGaMA and NSSO Rounds, the data challenges plaguing these surveys are limiting their true potential. Data gaps, periodicity gaps, incomplete coverage and quality gaps continue to hinder the effectiveness of these surveys. Coupled with irregular intervals between surveys, limited sampling and geographical limitations, many of the challenges faced by the Government in collecting data for the Millennium Development Goals between 2000 and 2015 persist in the next round of global targets. Moreover, with the separation of hunger and nutrition as a separate target, new challenges like identification (target populations) and specificity (specific questions to appraise indicators) are bound to arise.

The gaps and challenges will need to be addressed immediately if actions and efforts to reach the set goals are to be impactful. The importance of data collection and M&E practices are needed for any of the 17 SDGs but in the case of hunger and nutrition are critically important as they provide the necessary information to respond to changes and trends. For this, the Indian government will have to push towards correcting these data gaps and challenges by implementing needed changes in:

- The way data is gathered, recorded and presented,

- Designing surveys such that they incorporate more indicators and the entire range of target populations, and

- In the way data is monitored and evaluated.

For example, the government’s aversion to using monitoring and evaluation services of international bodies like the United Nations has to be dismantled or that specific surveys targeting age groups from children to adolescents to the elderly need to be developed.

In a positive development of digitisation of existing data collection infrastructure, the Ministry of Women and Child Development has launched an Information and Communication Technology enabled Real Time Monitoring (ICT-RTM) module of its Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) programme, which will specifically monitor nutrition services. If the Indian government can institute similar changes quickly, the possibilities of achieving the desired targets and being the driver towards realising these SDGs can be a reality. Without them, while India will continue to battle these national negatives, the overall value of its actions will always remain limited.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV