Image Source: Getty

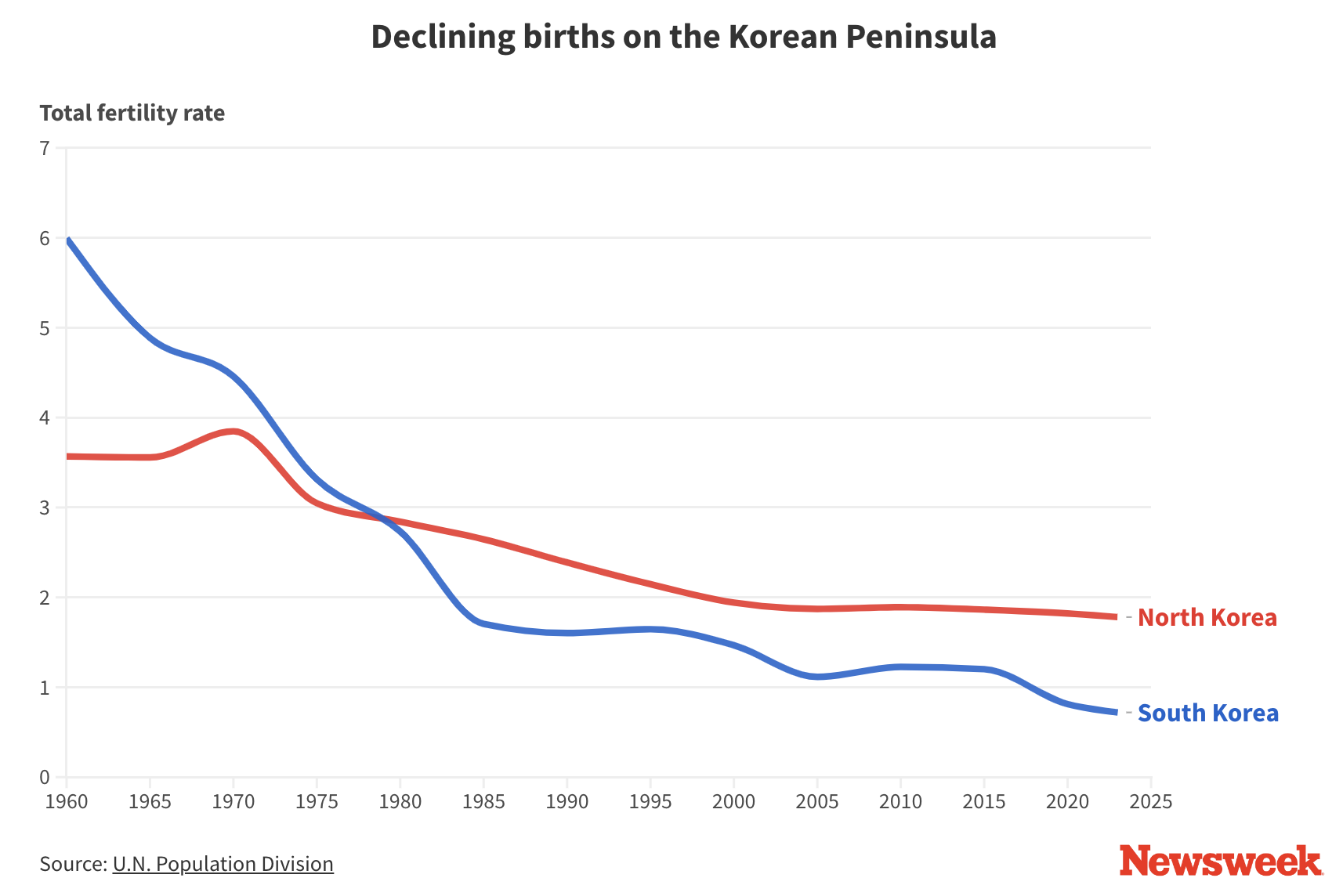

The East Asian region is experiencing a population crunch, threatening its economic and geostrategic competitiveness. Among the major economies of East Asia, South Korea has both the region and the world’s lowest fertility rate. In 2023, South Korea’s Total Fertility Rate (TFR, the average number of children a woman will have in her reproductive age) stood at 0.72, well below the replacement level of 2.1 required to maintain a healthy and stable population. This decline has severe implications for South Korea’s sustainable economic growth. However, the birth dip is also becoming a serious national security issue, affecting conscription and military preparedness. Therefore, amidst the intensifying security competition in Northeast Asia, it becomes important to understand the national security implications of this issue.

Among the major economies of East Asia, South Korea has both the region and the world’s lowest fertility rate.

Demographic decline and national security

South Korea’s low TFR has several consequences, such as an ageing population, slower economic growth, and high healthcare costs. These declining demographics also have serious national security implications: they influence sources of future conflict, affect national power, and change the nature of conflict. Moreover, the shrinking population threatens South Korea’s military preparedness. These concerns are amplified due to its economic status and strategic geography. As a result, to offset the effects of its low TFR, the country has maintained fully-staffed armed forces, as it technically still remains at war with its neighbour—North Korea. As per its law, all able-bodied men over 19 are “obliged to serve in the military” for at least 18 months, whereas women can serve voluntarily.

Nonetheless, due to the population shrink, the current military strength of South Korea accounts for just 40 percent of North Korean troops, which are around 1.14 million. It is already struggling to maintain its armed forces at full strength. Choi Byung-ook, a national security professor at Sangmyung University, has mentioned that “downsizing of the force will be inevitable” in the coming years. In 2022, the number of military personnel fell below the 500,000 benchmark for the first time. In contrast, North Korea maintained a force of about 1.28 million, and this difference is expected to become more severe, as shown in Figure 1. Experts from the Korea Institute for Defense Analyses have projected the number of South Korean military personnel to decrease to 396,000 by 2038.

Figure 1: Declining fertility rate in the Korean Peninsula

Source: Newsweek

*Although both Koreas face a decline in their population, North Korea’s fertility rate (1.78) is still higher than that of South Korea (0.72)

South Korea’s declining fertility rates: Cause and impact

In 2020, for the first time, the South Korean population hit a death cross—a state where the death rate surpasses the birth rate. There were only “275,815 births…compared to 307,764 deaths, reflecting a 3.1 percent increase in fatalities” from 2019. Despite perpetual and consistent efforts by the government, the fertility rate is expected to decrease in the coming years. It is projected to fall to 0.68 in 2024 and the population is projected to fall to 36.22 million by 2072. The situation has become so precarious that in May 2024, South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol declared the declining fertility rates a national emergency, announcing a plan to establish a new government ministry, the Ministry of Population Strategy Planning. The current population of South Korea stands at 51.7 million.

Despite perpetual and consistent efforts by the government, the fertility rate is expected to decrease in the coming years. It is projected to fall to 0.68 in 2024 and the population is projected to fall to 36.22 million by 2072.

In South Korea, the issue of low fertility rates is highly complex, driven by multiple factors, including a competitive workforce, gender inequality, long working hours, high costs of living and child healthcare, among many others. A 2022 Population Health and Welfare Association survey highlighted that 65 percent of South Korean women do not want children. Among other reasons, women have blamed the patriarchal culture of South Korea as a cause for their ‘baby strike.’ Therefore, to address the systemic issues, President Yoon has pledged to implement various methods to lighten the burden on parents and expecting couples: making their work schedule flexible, providing paternity leave and incentives, and boosting parent leave allowances. The effects of low fertility rates are increasingly evident in South Korea. The lack of a young workforce and the ageing population have also increased the “fiscal burden of public pensions and health care.” Simultaneously, there is a decline in school enrolment in South Korea. In 2024, the number of children in elementary schools “fell below 60,000 for the first time.”

Military preparedness and declining demographics

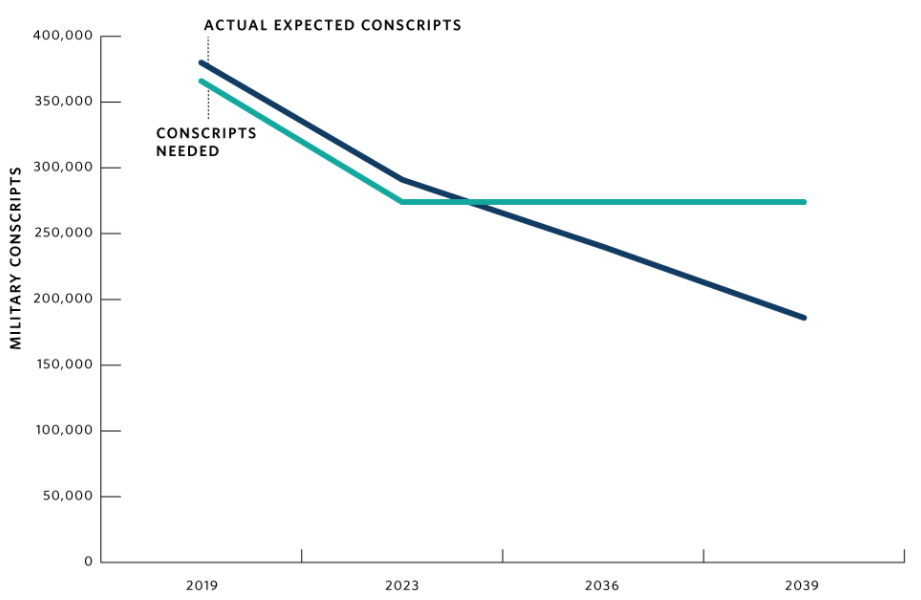

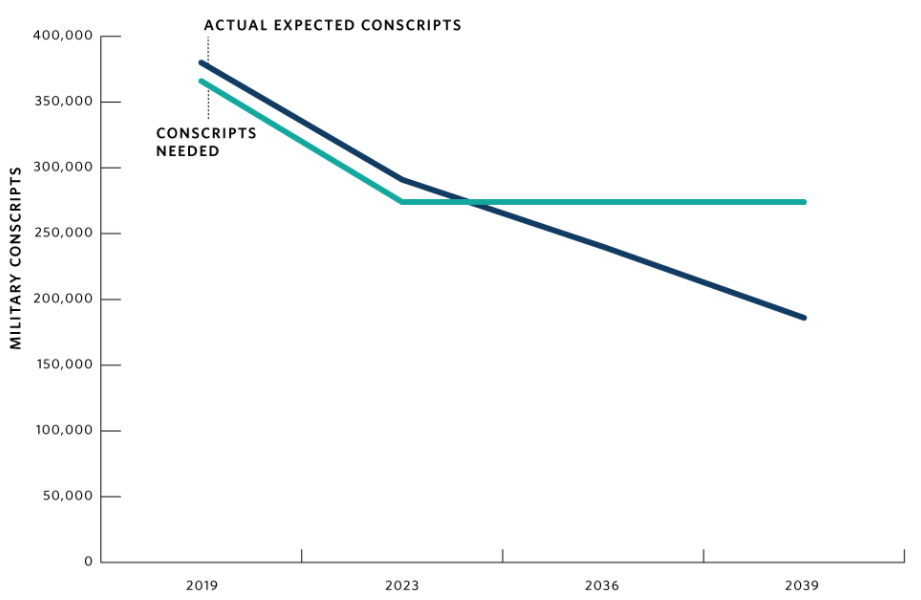

Apart from its socio-economic implications, demographic decline has impacted the country’s military preparedness, particularly its military conscription. The country is witnessing a decreasing number of young men in military service, as illustrated in Figure 2. For instance, in 2017, there were 620,000 active-duty military personnel in South Korea’s army, which went down to 500,000 in 2022. In future, to maintain a standard troop level, South Korea needs to conscript 200,000 soldiers each year. However, with the declining population, only 125,000 men would be available to defend the nation in the next 20 years.

Apart from its socio-economic implications, demographic decline has impacted the country’s military preparedness, particularly its military conscription.

South Korea also faces a severe shortage of commissioned and non-commissioned officers (NCOs) in the military. The recruitment targets were not fulfilled as there was a shortage of 550 commissioned officers and 4,790 NCOs in 2023. The retention crisis in the military has further exacerbated the issue. According to data, the number of commissioned officers leaving the military academy early has increased. 122 officers left in 2024 as opposed to 48 in 2023, a 2.5 times increase. Although technology has enabled hi-tech wars, human resources are still indispensable for national defence. Many scholars have highlighted the population as a resource, suggesting the critical linkage between the population and military power.

Figure 2: Difference between Actual Expected Conscripts and Conscripts Required in South Korea

Source: Carnegie

Age structure defines a state’s national security by including the “number of youth available as military manpower.” South Korea is experiencing an increase in mature age structures due to a low TFR and longer life expectancies. A mature age structure occurs if fertility rates decrease over a prolonged period, with an accelerating increase in life expectancy. With a gradual decrease in working-age adults and below-replacement level fertility, every “generation gets smaller and smaller, leading to a proportional decrease in size.” Nonetheless, countries with mature age structures can compensate for their lost human resources with the help of technology, alliances, and efficiency, though some issues still persist.

Technology as an enabler: Will it work?

South Korea has focused on technology as an enabler to offset this decline. It is driven by its 2022 Defence Innovation 4.0 plan, “an initiative to employ technologies to build a smarter military and address concerns of troop shortages.” The plan involves leveraging technologies like border surveillance systems along its eastern flank and coastal border with North Korea. For instance, in 2022, for the first time, South Korea established a dedicated team, known as the Army Tiger Demonstration Brigade, “a new unit meant to preview the future of ground fighting with drones, artificial intelligence and other advanced systems.” The plan is to transform all combat brigades by 2040 on similar lines, preparing for a future warfare scenario. Simultaneously, the country will reorganise its military structure from eight to two corps and 38 to 33 divisions by 2022 and 2025.

Countries with mature age structures can compensate for their lost human resources with the help of technology, alliances, and efficiency, though some issues still persist.

In this effort, technological tools and their adoption, such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), has substantially reduced the demand for personnel in the military to handle state-of-the-art weapons, but still, in critical areas within the military, human intervention plays a strategic role. Adaptability, agility, and precision are necessary military characteristics that can only be incorporated with human experience. For example, the Russian-Ukrainian war of attrition has highlighted the importance of manpower and conscription, particularly in a protracted conflict with a high casualty rate. The European war has showcased the importance of a large military and its importance for mobilisation. This phenomenon is an example of the importance of manpower during wars, particularly for South Korea, which is witnessing a declining population.

The current measures addressing the South Korean population problem remain half-baked and incomplete in addressing systemic factors. Their limited benefits will likely pay dividends only in the long term. Thus, to account for the military risks and threats in the short to mid-term, particularly amidst intensifying regional geopolitical contestation, it would be prudent for South Korea to bring in targeted incentives for its military conscription. Increasing women’s recruitment in its military has been a successful model, which needs to be continued. However, immigration can also be looked at as an attractive source of manpower going forward, serving both its military and economic needs. For this, the first step would be for the government to conduct extensive outreach requiring domestic deliberation with its citizens.

Abhishek Sharma is a Research Assistant with the Strategic Studies Programme at the Observer Research Foundation.

Torunika Roy is a PhD Candidate in Korean Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV