-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

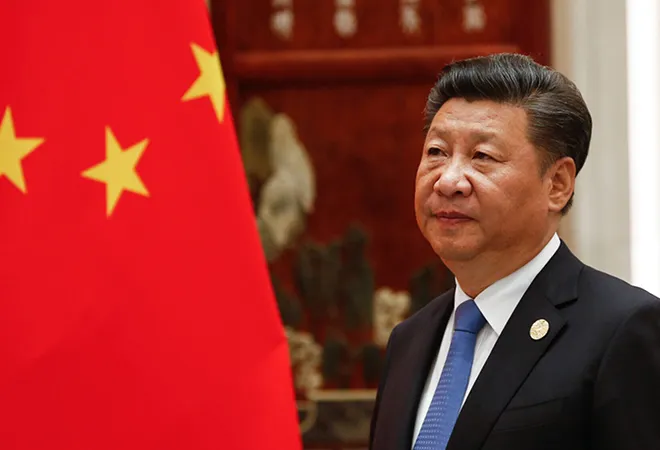

China’s recent anti-corruption campaign has been designed to plug any gaping holes in China’s national security.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) seems to be taking the proverbial warning far too seriously that Caesar's wife must be above suspicion. This is evident from the direction of CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign.

The CCP reckons that the chink in its armour is the cadres’ kin. New guidelines issued by the CCP relate to the business interests of officials’ spouses, their children and spouses. The aim is to limit the immediate families of officials from exploiting the aegis of the CCP to further their interests. Officials will be expected to disclose to the Party the business activities of their kin, and suppression of information may attract severe punishment. In March 2022, the CCP prohibited the spouses and children of ministerial-level officials from owning real estate overseas or equities registered abroad. They will also be barred from opening accounts in overseas financial institutions.

Officials will be expected to disclose to the Party the business activities of their kin, and suppression of information may attract severe punishment.

A commentary in the CCP’s mouthpiece, People’s Daily, justified the new regulations on the grounds that the Party’s mission was to serve the people and not special interest groups. It went on to add that many high-ranking officials were helping their kin to rake in illegal profits, which was denting the Party’s image. At a Politburo meeting on 17 June, Xi asserted that whilst China was at the cusp of an “overwhelming” victory in the battle against corruption, more work was required to meet the challenge. He also said that the need of the hour was to ensure that officials did not fall into the trap of corruption because they “do not dare to, are not able to, and do not want to”.

A complex set of factors may have influenced the anti-corruption campaign. There is a growing realisation that instances of high-profile bribery anger the public and threaten political legitimacy. This has also been influenced by events taking place in other authoritarian regimes. An incident of a vendor setting himself ablaze after an altercation with the local authorities in Tunisia in 2011 toppled a two-decade-old single-party regime with corruption and high inflation playing the catalyst. The aftershocks of the turmoil reverberated in Egypt and Libya with the single-party regimes of Hosni Mubarak and Muammar Gaddafi being overthrown. The incident stoked an uprising in Syria against Bashar al-Assad and fomented political turmoil in the Middle East. As an adaptive authoritarian regime, which constantly studies developments in other despotic states and recalibrates its survival strategy, one of Xi’s first initiatives when he came to office in 2012 was the purge those indulging in financial turpitude.

An incident of a vendor setting himself ablaze after an altercation with the local authorities in Tunisia in 2011 toppled a two-decade-old single-party regime with corruption and high inflation playing the catalyst.

Significantly, the new guidelines are being put in place ahead of the CCP’s National Congress, which will witness a power transition. Whilst Xi is expected to get an unprecedented third term in office, new leaders will fill in the positions vacated by incumbents.

Given the resentment against Xi in a section of the CCP due to the economic impact of the zero-COVID strategy and the abrupt rupture of political ambitions of some officials due to his prolonging his tenure, such regulations will give him influence over the new elite in China.

Another factor that may have forced the CCP to tighten the screws on its errant cades is its ongoing tensions with the West. The kin of CCP officials is known to use offshore entities to hold assets. A report by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists linked the relatives of Mao Zedong, Xi Jinping’s brother-in-law, and former CCP General Secretary Hu Yaobang to offshore commercial activities managed through the legal firm Mossack Fonseca and Co. These make China’s elite vulnerable to sanctions by the United States (US). In light of the human rights violations in Xinjiang province and Hong Kong, the US has sought to freeze any assets that the CCP elite holds in the country. In recent times, Wang Chen, a member of the elite Politburo, and former Xinjiang party chief Chen Quanguo have been in the crosshairs of such action. The new regulations on probity for party members are a guard rail in the face of more severe the US actions in the future.

In light of the human rights violations in Xinjiang province and Hong Kong, the US has sought to freeze any assets that the CCP elite holds in the country.

Lastly, and more importantly, the incidents in the run-up to the 2012 Party Congress seem to be a big factor in the new rectitude regulations. After Chongqing Police Chief Wang Lijun reported to Politburo member Bo Xilai that the latter’s wife had a hand in the poisoning of the United Kingdom (UK) businessman Neil Heywood, an altercation ensued that forced Wang to seek asylum at the American consulate at Chengdu. Since the US and China were on relatively congenial terms, it ensured that Wang was handed back to the Chinese authorities. Media reports disclosed that Heywood was the conduit between Western corporates and the CCP power elite. But disturbingly for the CCP, media disclosures tied Heywood to British intelligence, though the UK government denied that he was employed with the secret service. In recent years, ties between China and the US have deteriorated. Xi warned that China was facing the most “complicated internal and external factors in its history”, and that the challenges were “interlocked and mutually activated”. The CCP fears that western powers may instigate regime change in the nation. Given this background, there seems to be a substantial revaluation in the CCP’s thinking from looking at graft as purely a social evil. The anxiety remains that as in the case of Gu Kailai, human greed may facilitate foreign intelligence agencies to access the innards of China’s political system and destabilise it from within. The probity norms for members thus seek to plug a gaping hole in China’s national security.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Kalpit A Mankikar is a Fellow with Strategic Studies programme and is based out of ORFs Delhi centre. His research focusses on China specifically looking ...

Read More +