Image Source: Getty

Research studies over the last decade have shown that out-of-pocket expenditures (OOPE) in health push 3 percent to 7 percent of Indian households below the poverty line every year, with rural and poorer states facing a higher impact. Disadvantaged groups bear a greater financial burden from OOPE in health, and therefore, it has lately been a high-focus area of health policy in India. On 25 September 2024, the Government of India (GOI) released the National Health Account (NHA) estimates for India for the years 2020-21 and 2021-22—a period when India saw increased investments being channelled into the health sector—which shows accelerated progress in the reduction of OOPE.

Disadvantaged groups bear a greater financial burden from OOPE in health, and therefore, it has lately been a high-focus area of health policy in India.

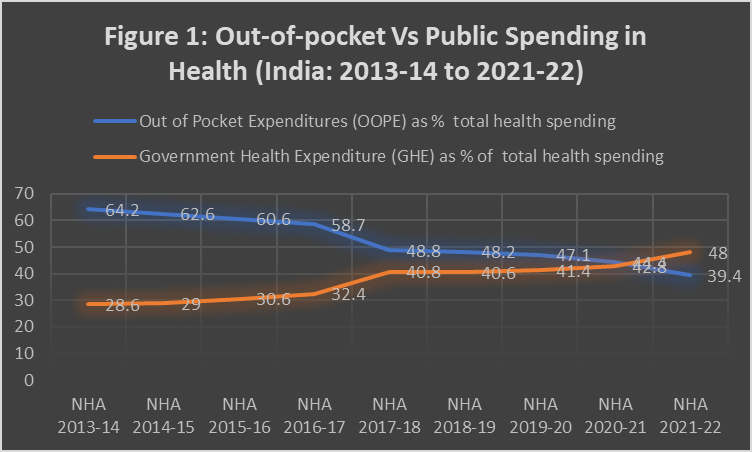

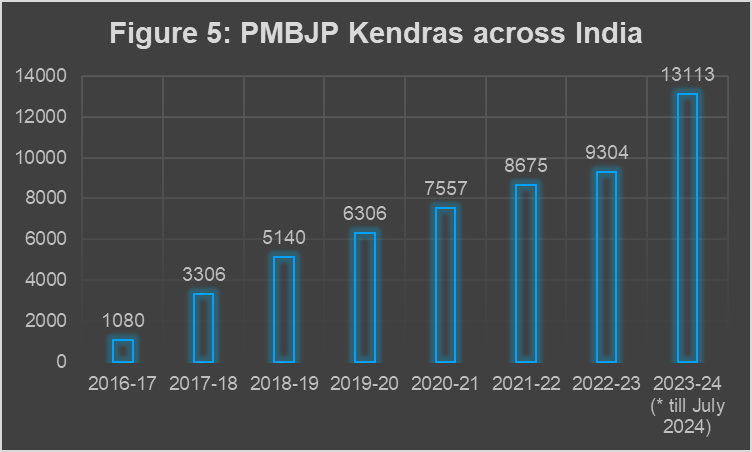

The latest NHA estimates, available for 2021-22, show dramatic changes in health financing parameters in the last decade. Between 2013-14 and 2021-22 (Figure 1), a sharp decline of OOPE in health is observed, from 64.2 percent in 2013-14 to 39.4 percent in 2021-22, the year for which the latest data was released by the government. While the increased health spending was necessitated by the pandemic, it is clear from historical data that this has been an ongoing trend throughout the decade. During the same period, the Government Health Expenditure (GHE) increased sharply from 28.6 percent to 48.0 percent. The proportion of GHE overtaking the OOPE component is a historic moment for India’s health policy, many years in the making.

Source: Compiled by the author from different NHA reports by GoI.

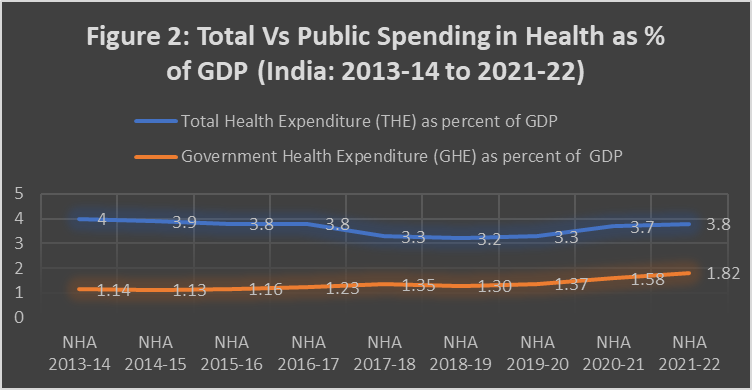

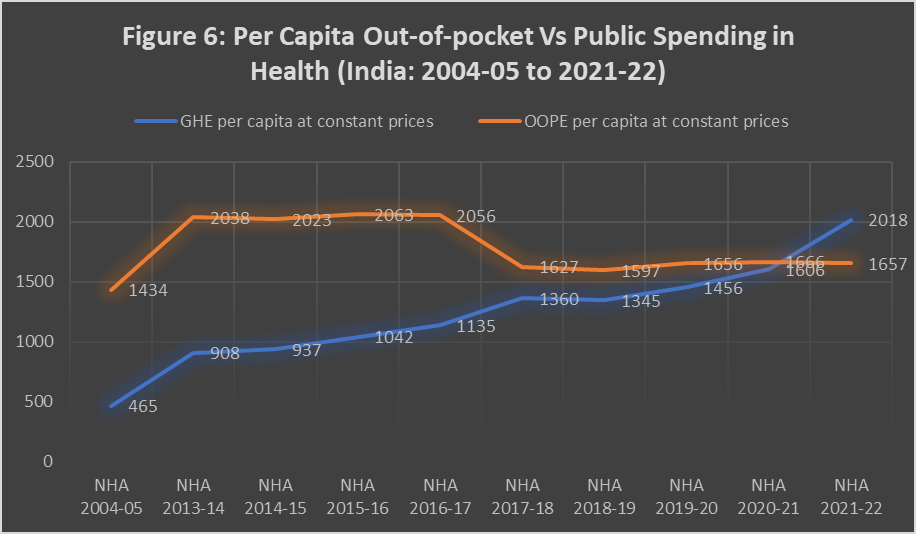

The past decade has also been a period when the total health expenditure (THE) as a percentage of GDP came down (Figure 2). In other words, increased public spending—from both state and the union governments—was the primary driver transforming the health financing landscape of the country, triggering sharp decreases in the health spending burden on Indian families. At the same time, despite the improvement, 39.4 percent of the total spending still remains out-of-pocket, signifying a major policy challenge for the coming years. Looking at data from 2021-22, India still has a long distance to cover to reach the National Health Policy(NHP) 2017 target it set for itself, of reaching 2.5 percent of GDP worth of government expenditure in health by 2025.

Source: Compiled by the author from different NHA reports by GoI.

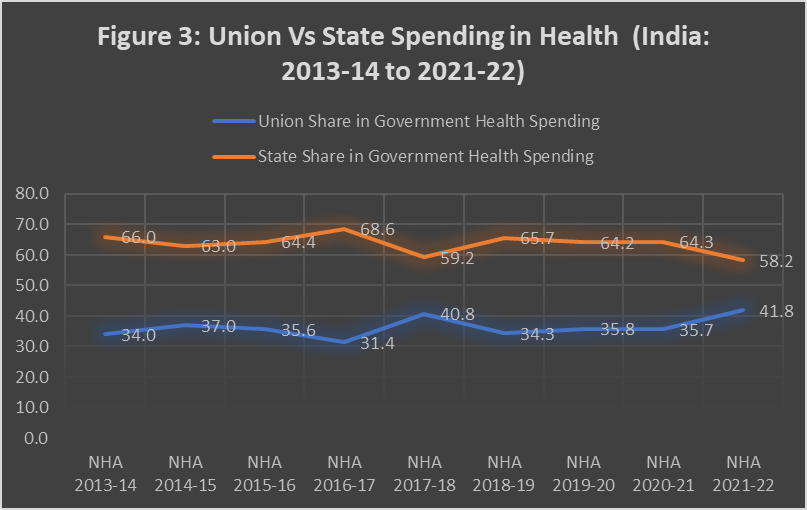

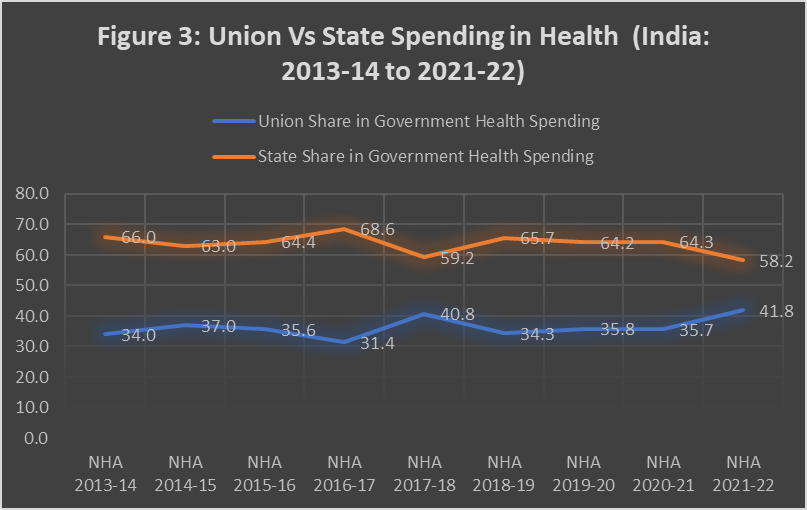

Historically, about two-thirds of overall GHE has been borne by the states and one-third, by the union government. As seen in Figure 3, increased spending by the Union government during the pandemic has altered the composition by a small margin. However, post-2022, utilisation of Union Budget allocations within health has not been reassuring, with large amounts of unspent money remaining at the end of the year compared to the budget estimates. It was observed elsewhere that despite disruptions affecting the actual spending within the health sector, and the need for pandemic-induced emergency funding subsiding, actual allocations by the union government have not gone down to pre-pandemic levels, which is indicative of the possibility of further reductions in OOPE in the future driven by government action. With the ambitious expansion of AB-PMJAY to include all 70+ citizens and the possibilities that the scheme offers for the government hospitals to plough back money into the public system, the capacity to absorb funds in the public sector is bound to improve.

Source: Compiled by the author from different NHA reports by GoI.

Both state governments as well as the union government will need to make sure that health spending does not slip back to pre-pandemic levels for India to have any real chance of achieving the national target of reaching 2.5 percent of GDP worth of government expenditure in health by 2025. The upward momentum will need to be maintained, whether it is led by the union or state governments, ideally by both. Health is constitutionally the primary responsibility of the states, and the efforts towards tax devolution were expected to trigger large increases in funds for health at the state level. However, fiscal devolution from about 32 percent of overall tax funds during the 13th Finance Commission award period (2010–2014) to 42 percent during the 14th Finance Commission award period (2015–2019) did not quite translate into higher healthcare spending by the state governments. It is hoped that the Indian health system does not fall into the panic-neglect cycle that usually follows pandemics across the world.

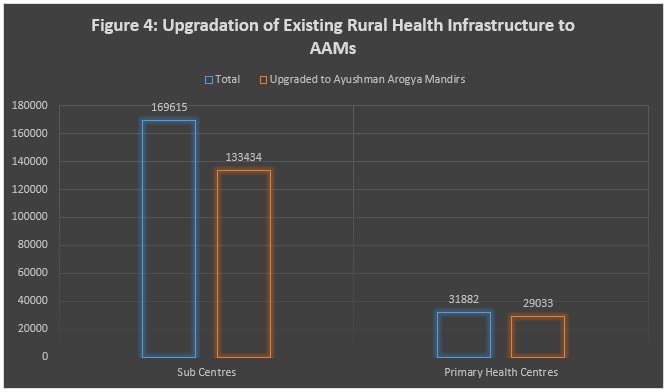

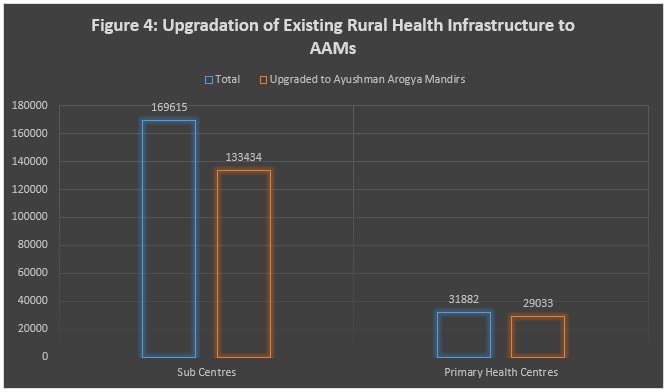

In tandem with the transformation of the health financing scene, there have been multiple initiatives contributing directly and indirectly to the reduction of OOPE. Most well-known is AB-PMJAY, a partnership between the union and state governments, which authorised hospital admissions amounting to 69 million across India from its inception in 2018. Across 748 districts running 1,530 centres with more than 10,000 hemodialysis machines, the lesser-known Pradhan Mantri National Dialysis Programme (PMNDP) has helped around 2.5 million poor patients across the country from its inception in 2016. Launched in 2018, India now has 1.75 lakh functional Ayushman Arogya Mandirs (AAMs, earlier called Ayushman Bharat Health and Wellness Centres) providing comprehensive primary healthcare, primarily in the rural areas.

Comprehensive primary healthcare near home addresses this issue, simultaneously addressing the financial burden on families and overcrowding of hospitals.

Through upgraded sub-centres and primary health centres, AAMs provide a comprehensive range of services extending beyond maternal and child healthcare to include non-communicable disease management, palliative and rehabilitative care, oral health, eye and ENT services, mental health support, and first-level care for emergencies and trauma. AAMs also include the provision of free essential medicines and diagnostic tests. Historically, many patients visited hospitals only when their situation became unmanageable, for conditions that could have been addressed earlier if there were functional primary healthcare infrastructure in rural areas. Comprehensive primary healthcare near home addresses this issue, simultaneously addressing the financial burden on families and overcrowding of hospitals. As Figure 4 shows, more than 80 percent of existing primary-level public infrastructure has already been upgraded, showing an unprecedented pace.

Source: Compiled by the author from different government sources.

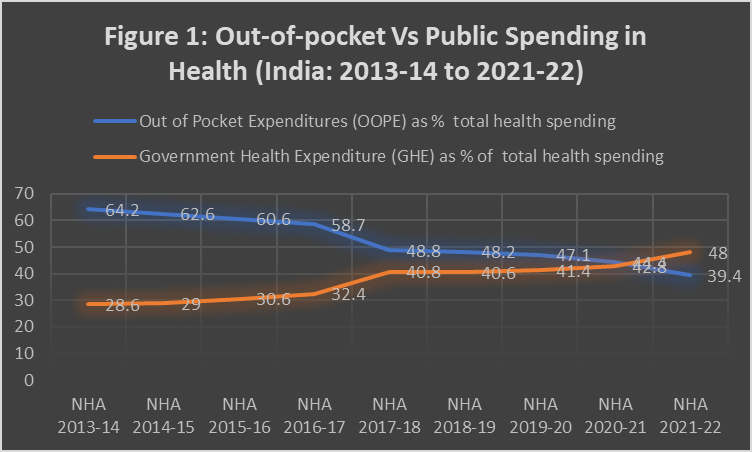

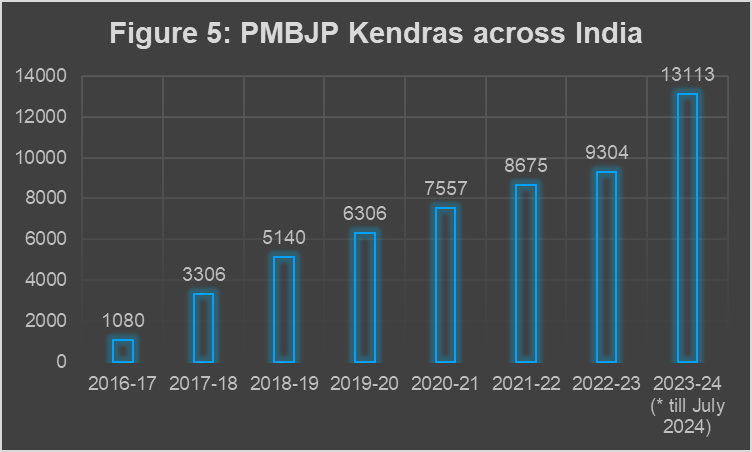

Another even lesser-known scheme with a major impact on the composition of health financing within India is the Pradhan Mantri Bhartiya Janaushadhi Pariyojana (PMBJP), which remains a low-profile, but high-performing initiative of the NDA government. It was launched in 2008 by the earlier UPA government but had only 80 medicine shops set up till 2015. In recent years, the scheme has expanded aggressively across India (Figure 5), leading to household savings of thousands of crores of rupees. The OOPE decline over the last decade, therefore, had multiple contributors.

Source: Compiled by the author from GoI’s PMBJP portal

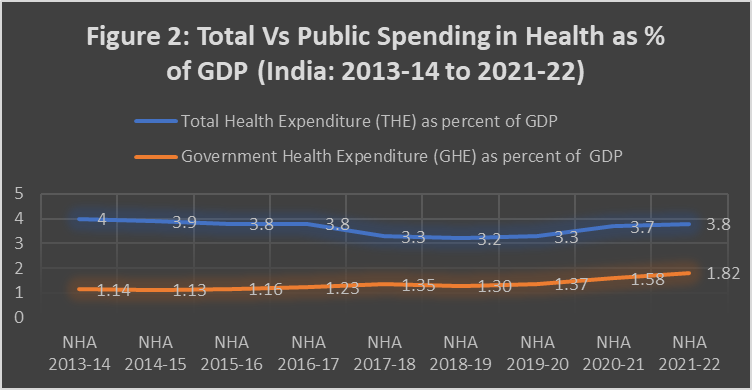

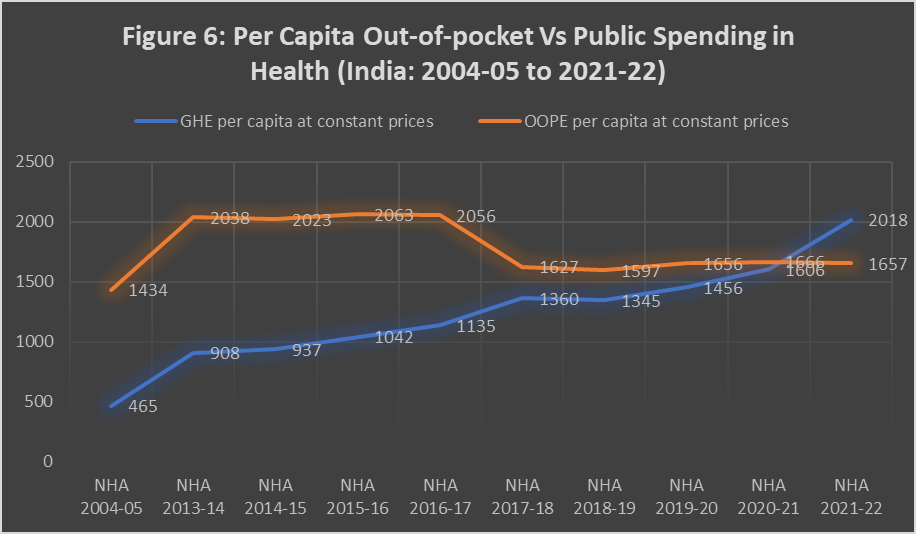

Figure 6 explores longer-term trends of movements of per capita government spending on health and per capita OOPE in India adjusted for inflation. Over the years, from 2004-05 to 2021-22, there is a considerable increase in public health spending, rising from INR 465 per capita in 2004-05 to INR 2018 per capita in 2021-22, indicating a strengthening of government investment in health, primarily driven by economic growth expanding the resources available for the sector, and the pandemic necessitating augmented allocations. However, OOPE still remains high, peaking in 2015-16 at INR 2063 per capita before showing a gradual decline, settling at INR 1,657 in 2021-22. The gap between per capita OOPE and GHE narrowed over time, till 2021-22 when per capita GHE overtook OOPE, reflecting government efforts to reduce the financial burden on individuals. As discussed earlier, OOPE remains a significant part of overall health spending, at about 40 percent of overall health spending, signifying a formidable challenge.

Source: Calculated by the author based on information compiled from different NHA reports by GoI.

It is important that the current momentum in government funding within the health sector is maintained if India has to get near the national goal of the public sector spending 2.5 percent of GDP on health. While there is a range of recent initiatives contributing to the goal of bringing down OOPE further, many challenges remain. For example, while a robust distribution system is now in place for generic medicines, India still has an unfinished agenda of ensuring the quality of medicines and enforcing regulations in pharmaceutical manufacturing. Fake manufacturers are still able to infiltrate the public sector supply chain, as a recent case of spurious drugs in Maharashtra has demonstrated. AB-PMJAY, focusing on secondary and tertiary care, and AAM, focusing on comprehensive primary care, are progressing, however, there is still a long way to go in terms of integrating these two platforms to ensure a continuum of care, connecting public and private infrastructure across levels of care. Rare diseases are another area where India needs policy interventions addressing population needs.

The pandemic has proven to the world that health is a major pillar of national security. Given India’s low baseline in terms of health investments, a focused inflow of capital expenditure like in drinking water, sanitation, and housing sectors is needed to make amends for the historical neglect of the health sector. If successful, India will be able to continue the dramatic reduction of OOPE and become a global case study, elements of which will be adapted and scaled in different developing country settings across the world.

Oommen Kurian is a Senior Fellow and the Head of Health Initiative at the Observer Research Foundation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV