With a full budget to follow in July after the elections, the Interim Budget 2024 was not expected to make any major announcements. However, the Budget did announce a few new initiatives in the health sector. The new budget documents also allow us to look at health allocations and spending in the past few years during and after the pandemic. Given the uncertainties of the pandemic, the last few budgets have seen sharp differences between the budget estimates (BE), revised estimates (RE), and actual spending. Along with a quick analysis of the health numbers in the interim budget, this article tries to make sense of the broad trends in health spending in the last six years, based on data on budget estimates, revised estimates, and actual spending from the period.

Announcements in the Interim Budget

Despite being an interim budget during an election year where big initiatives are not expected, there were several important announcements and updates made for the health sector. The Finance Minister, Nirmala Sitharaman, announced plans for establishing additional medical colleges by utilising existing hospital infrastructures, aiming to address the shortage of healthcare professionals and meet the increasing demand for medical education in India. In April 2023, the Union Cabinet sanctioned the creation of 157 new nursing colleges with a budget allocation of INR 1,570 crore, of which INR 1,016 crore is the central share. The latest budget documents indicate that so far, Detailed Project Reports (DPRs) for 86 colleges have been approved, and an initial funding of INR 2 crore each has been disbursed for the establishment of 73 colleges.

The Finance Minister, Nirmala Sitharaman, announced plans for establishing additional medical colleges by utilising existing hospital infrastructures, aiming to address the shortage of healthcare professionals and meet the increasing demand for medical education in India.

Also, the provision of cervical cancer vaccinations for girls aged 9 to 14 years, highlighted the government's focus on preventive healthcare, along with the introduction of the U-WIN platform for managing immunisation as part of Mission Indradhanush, which can help increase vaccination coverage nationwide and reduce vaccine-preventable diseases. Furthermore, the budget proposes the integration of various maternal and child health schemes into a single comprehensive programme, intending to streamline and enhance the effectiveness of healthcare services for mothers and children. Upgrades to Anganwadi centres are emphasised under the “Saksham Anganwadi” and “Poshan 2.0” schemes, to improve nutrition, early childhood care, and overall child development, positioning these centres as key community health resources.

The Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana’s extension to include all ASHA workers, Anganwadi workers, and helpers—around 1.5 million in total—recognises the vital role these frontline health workers play in grassroots healthcare delivery and seeks to provide them with comprehensive healthcare coverage. Assuming that there are five members per family, this is an expansion of potentially around 7.5 million new members to the scheme.

The Interim Budget numbers on health

Over last year’s revised estimates of INR 86,216 Cr for the health sector (including AYUSH and pharmaceuticals), this year’s overall health budget of INR 98,461 Cr marks an increase of INR 12,245 Cr, over 14 percent in nominal terms. At the same time, when compared to Budget 2023 estimates, the increase is a more moderate 2.6 percent, hardly covering inflation. However, the downward revisions in overall budget estimates for last year’s (2023-24) health allocations are not new, given the post-pandemic boost in the budget for health. It happened in 2022 as well, when the money assigned for COVID-19 preparations was unspent due to a lack of demand. It is a fact that the health sector has not yet seen a sustained increase in allocations and spending like drinking water is seeing now, and sanitation saw earlier. Also, infrastructure-focused schemes such as the Pradhan Mantri Swasthya Suraksha Yojana (PMSSY) and PM- Ayushman Bharat Health Infrastructure Mission (PM-ABHIM) which had seen low utilisation during the pandemic years have latest allocations being marginally lower than last year’s budget estimates. The revised estimates for last year for these schemes were considerably lower than budget estimates, indicating low utilisation, which needs to be corrected.

The plan to set up a committee to consolidate and enhance public hospitals under non-health ministries and PSUs is perhaps the most significant announcement for the health sector in this budget.

More importantly, a look at historical data proves that the National Health Mission budget seems to have plateaued, in real terms. It will not improve unless health human resource (HHR) gaps are addressed, particularly in rural hospitals and health centres. The government seems to have realised this, given the continuing focus on public sector-led medical education in this Budget as well. The pandemic has seen different ministries and Public Sector Undertakings (PSUs) pooling healthcare infrastructure for the public good. Taking this approach to the next level, Sitharaman announced during the Budget speech, the government’s plans to upgrade these hospitals to medical colleges. The plan to set up a committee to consolidate and enhance public hospitals under non-health ministries and PSUs is perhaps the most significant announcement for the health sector in this budget. This will add dozens if not hundreds of hospitals to the public sector health education infrastructure.

The pandemic year budgets: A closer look

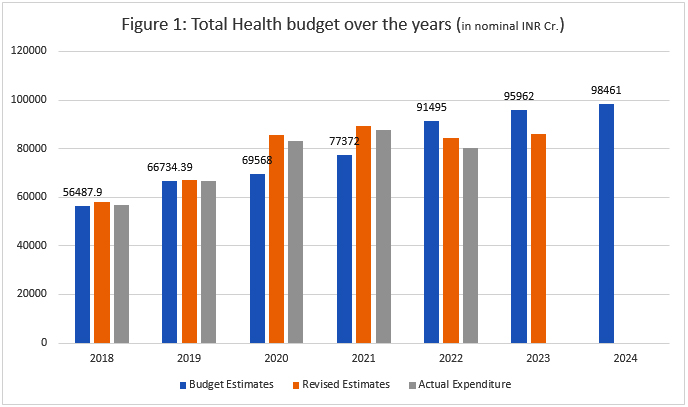

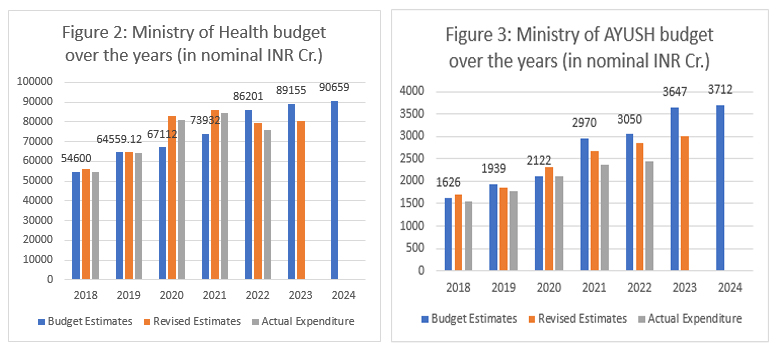

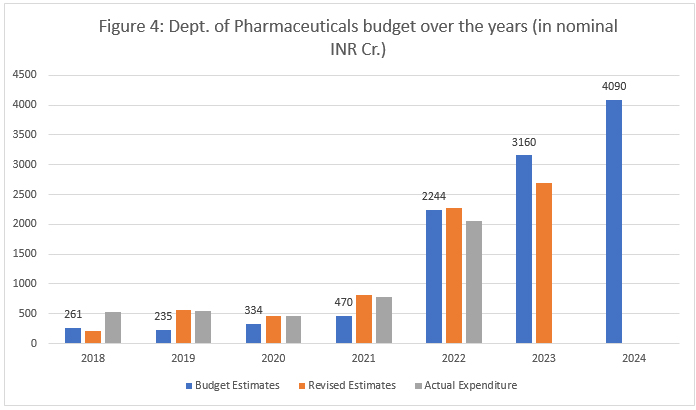

For this analysis, we will be considering the allocations to the Ministry of Health, Ministry of AYUSH, and Department of Pharmaceuticals together as health. The Department of Pharmaceuticals used to have a fairly small budget in the past, but with Dr Mansukh Mandaviya taking up the dual responsibilities as the Minister of Health and Family Welfare as well as Chemicals and Fertilizers of India, its budgetary allocations have gone up considerably, reflecting a unique convergence of and a strategic advantage in aligning healthcare policies and drug manufacturing practices.

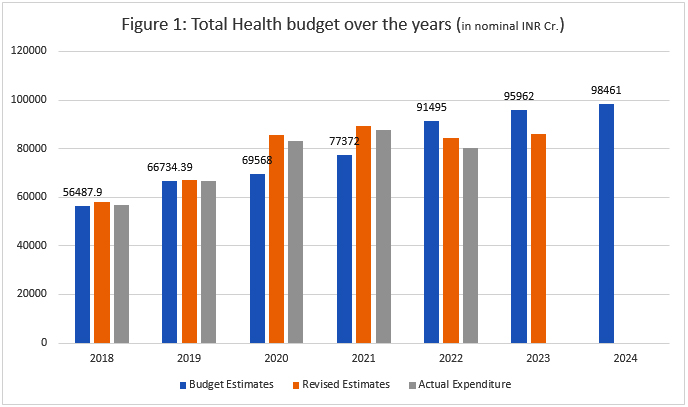

India still is nowhere close to the ideal government spending of 2.5 percent of GDP on health, as envisioned in the National Health Policy 2017 to be achieved by 2025. However, exigencies of the pandemic saw the public spending on health getting ramped up. Figure 1 shows how both the pre-pandemic years saw budget estimates, revised estimates and actual spending in a similar range. However, both 2020 and 2021 saw sharp upward revisions, to address the needs of the fight against the pandemic.

However, from 2022 onwards, the revised estimates have seen declining considerably, primarily due to the decreased need for pandemic interventions like vaccination, but also likely due to disruptions during the pandemic affecting many initiatives aimed at increasing infrastructural capacity in the health sector. However, these setbacks have not resulted in a downward revision of budget estimates, and the government has kept the health budget at the pandemic levels, with a focus on infrastructure creation and consolidation of a foundation on which a Universal health coverage (UHC) system can be built in India, focusing on healthcare infrastructure, medical education, and pharmaceutical production aligned with the country’s goals.

Source: https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/ Budget documents, various years, compiled by the author.

Source: https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/ Budget documents, various years, compiled by the author.

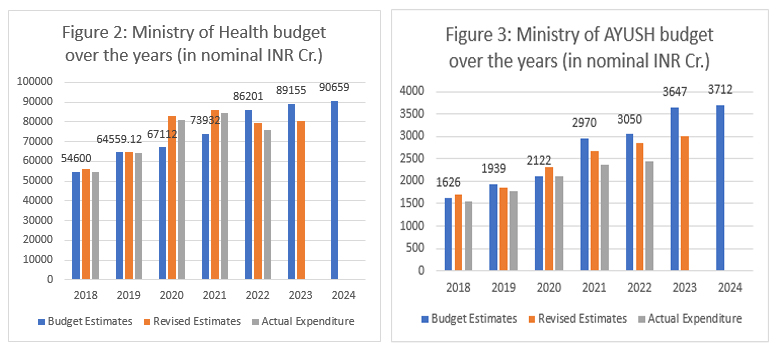

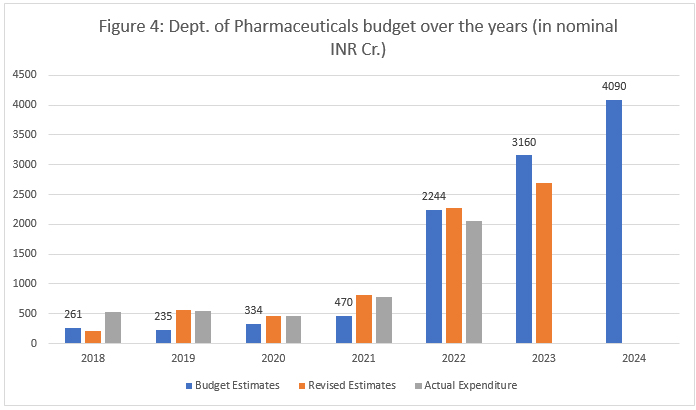

Figure 2 and Figure 3 look at the budgetary allocation and spending of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW)—constituting the Department of Health and Family Welfare as well as the Department of Health Research) and the Ministry of AYUSH. MoHFW as well as MoAYUSH, despite the former constituting more than 90 percent of the overall health budget, share similar trends during budget cycles, barring in 2021. Both MoHFW and AYUSH hospitals in the public sector were integrated into the overall healthcare strategy to manage the pandemic. However, during the peak, when healthcare services as well as infrastructure creation were widely disrupted, the curative services were predominantly handled by MoHFW, and AYUSH focused on telemedicine services with a focus on enhancing immunity, and managing chronic conditions. This may partly explain the underutilisation of funds within AYUSH during 2021, earlier than within MoHFW. Notably, the lack of utilisation has not impacted budget estimates in the corresponding years. The creation of capital assets within the head “Human Resources for Health and Medical Education” has seen a budget allocation of more than INR 5,000 Cr even when the actual spending in 2022 and revised estimates in 2023 have both been under INR 2000 Cr, pointing towards an intent to create public assets in medical education.

Source: https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/ Budget documents, various years, compiled by the author.

Source: https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/ Budget documents, various years, compiled by the author.

As discussed briefly earlier, one of the most important developments during the pandemic was the closer alignment between the health and pharmaceutical sectors, with a common minister taking charge in 2021. There was a realisation within the government about the need for a better balance between the requirements of the health sector and the capacities of the pharmaceutical sector. As a result, the pharmaceutical sector, an important pillar in India’s UHC plans has seen vastly improved budgetary allocation. Between 2018 and 2024, the allocations to the pharmaceutical sector have expanded by more than 15 times, as Figure 4 shows. This has yet not received the media attention it deserves.

Source: https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/ Budget documents, various years, compiled by the author.

To put it in a comparative perspective, the nominal budget allocation for pharmaceuticals was around one-sixth of that of AYUSH in 2018. However, it has overtaken allocation to the AYUSH ministry in 2024, primarily as a result of the renewed focus on self-reliance in the pharmaceutical sector. Both the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme as well as Jan Aushadhi scheme have seen substantial increases in this year’s allocation.

In short, the need for the injection of substantial resources into the health sector—like the way done in the sanitation sector and the drinking water sector—remains to be fulfilled, the Indian government seems to be focusing on important pillars of its UHC plans in the budgetary allocations, namely healthcare infrastructure, medical education, and pharmaceutical production. For that reason, despite disruptions affecting the actual spending within some of these heads, and the need for pandemic-induced emergency funding subsiding, the actual allocations have not come down post-pandemic (Figure 1). It remains to be seen whether the sector can absorb these funds in the coming year.

Oommen C. Kurian is a Senior Fellow and Head of Health Initiative at the Observer Research Foundation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV