-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Women have particular reproductive, safety, and biological needs that urban designing must cater to in order to make the entire cityscape more accessible and inclusive.

This article is part of the series — Catalysing Change: Women-led Development in the Decade of Action.

Urban planning exercises for the future involve a range of unique developments — from ‘defensive designing’ to prevent loitering and encroachment, to ‘community plazas’ to promote healthy social interactions and public spaces. While urban spaces evolve as per the needs of the community, the needs of vulnerable populations with specific requirements must be taken into consideration. Women have particular reproductive, safety, and biological needs that urban designing must cater to in order to make the entire cityscape more accessible and inclusive.

The feeling of overcrowding and congestion in public spaces, transport, and various parts of the city can make women feel unsafe due to perceived risk of anti-social behaviour by people in close quarters. According to Safetipin’s report on women and mobility in Bhopal, Gwalior, and Jodhpur, 82 percent women felt that overcrowding was a reason they felt unsafe.

Safety in this context means being protected from harassment in particular, rather than safety from a virus. It refers to a woman’s level of comfort and perception of risk while traversing different areas of the city, and security from “intentional criminal or anti-social acts, including harassment, burglary, vandalism.” Women are less likely to participate in the workforce when the perceived threat of crime against them is high.

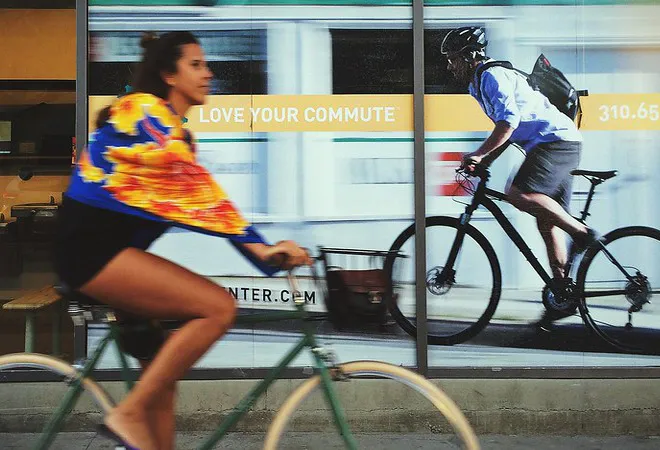

Safe mobility is a necessary element of the planning process — women travel for work, household chores, dropping children to school, and numerous other reasons.

It is crucial to have safe cities to achieve inclusive growth. Safe mobility is a necessary element of the planning process — women travel for work, household chores, dropping children to school, and numerous other reasons. Any pandemic-induced limitation in the number of people allowed to travel using public transport will limit the spread of the infection; however, these limitations will only exacerbate the existing problem of shortage of multi-modal public transport connections, and lead to risky overcrowding. According to a report for the national centre for biotechnology information, in a city like Mumbai, during the evening peak hour, there already exists a 20 percent shortage of public transport during pre-pandemic days, which is expected to reach 25 percent if physical distancing is imposed. A report also shows that the country would need close to 666,667 buses for 25 million commuters daily. However, currently it only has about 25,000 operational buses. This shortage will create more congestion in waiting areas like platforms and interchanges, which would exacerbate the feeling of risk and may prevent women from accessing many spaces. A careful consideration of providing multiple modes of transport during the ‘safe window’ of time that women use to travel must be made.

Safety audits in the form of creating a city-map of areas where crime is known to be high, the ostensible factors that contribute to it (lack of lighting, sparse population, etc.), and focused interventions in these areas must be made for accessibility and participation in city life to increase. Urban design must promote safety in numbers whilst avoiding the risk of congestion.

The use of CCTV cameras, street lighting, and shards of glass on top of boundary walls have the similar purpose of moderating unwelcome human behaviour like vagrancy, theft, harassment, and encroachment. CCTV cameras and lighting go far in making women feel safer and enables them to participate in a city’s nightlife. Cities need to first ensure its citizens feel safe from anti-social behaviour, before questions about safety from overt surveillance are considered. Therefore, increasing CCTV cameras with a specific task force dedicated to dealing with crimes and harassment against women will go a long way in creating an effective and safe atmosphere, without the added setback of ‘too much surveillance.’

Cities need to first ensure its citizens feel safe from anti-social behaviour, before questions about safety from overt surveillance are considered.

Cities across the world have introduced concepts like uncomfortable benches and spikes outside establishments to prevent people from getting too cosy and staying in public spaces indefinitely. However, benches, hand rails, and other forms of supportive street furniture are important for women travelling with children, pregnant women, the elderly, and the disabled. The golden ratio of ensuring accessibility whilst preventing loitering must be achieved by carefully collecting data of footfalls and usage of space to prepare amenities and street furniture particularly for that space. These benches and handrails must also take into consideration a woman’s height and specific requirements. Hand grips in buses and trains currently are also at an inconvenient height for women — factors that make public transport uncomfortable.

City design must take into consideration the fact that a woman’s role within the city is different from a man’s — as soon as she steps out of her home, she uses the city’s services for work, childcare, household chores, and various other gendered activities. A society where there is equitable distribution of professional and household work between sexes is the goal; before that ideal state is achieved, however, urban planning must involve the ‘mobility of care.’ The mobility of care framework recognises, measures, values, and accounts for travel associated with those care and home-related tasks. Safe, well-lit footpaths for travelling short distances for household chores, and ensuring safe travel for and with children, are some of the ways in which the entirety of the mobility chain can be supportive of care and home work. Eventually, mobility of care and the policy decisions regarding it should be gender neutral (as caregiving should not just be a woman’s role, and income generation just a man’s role).

‘Care at work’ would involve employers being mandated by government policy to provide these necessities, and incentivising the efficient delivery of care facilities that support working women.

Similarly, to increase and sustain a larger female urban workforce, crèches and sanitary toilets in workplaces should be made a statutory condition regardless of company turnover or the number of female employees in a company. ‘Care at work’ would involve employers being mandated by government policy to provide these necessities, and incentivising the efficient delivery of care facilities that support working women.

Several cities like Mumbai have installed ‘multipurpose houses for working women’ and hostels near places of work and education, that include childcare facilities and training centres. While these interventions are necessary, we must strive for a society with less demarcations and segregations, and more healthy interactions amongst all genders. Segregated lines for women in airports, malls, and security may be warranted in countries where safety statistics are still abysmal; however, this obvious physical separation creates mental barriers and divisions. Instead, authorities must invest in better security equipment to not require hand-held metal detection devices.

The future of gender-sensitive planning must cater to the safety and inclusion of women so that they are able to fully participate in city life. Finding the ‘goldilocks zone’ of safety in numbers without congestion, defensive design that is not hostile architecture, and ‘mobility of care’ and ‘care at work’ that does not segregate are essential elements to boost female city participation in an equitable manner.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Aditi Ratho was an Associate Fellow at ORFs Mumbai centre. She worked on the broad themes like inclusive development gender issues and urbanisation. ...

Read More +