Development finance and corporate banks alike have long wrestled with the issue of banking the unbanked in the developing world, which would encourage broad-based socio-economic development on the one hand, and on the other, greater product distribution for the private sector banking institutions.

However, bringing greater financial inclusion to the bottom of the pyramid no longer means universal branch bank account ownership. Nowhere is this more evident than in Africa, particularly in one of the continent’s emerging fintech hubs, Kenya.

M-Pesa, whose name derives from the Swahili word for money ‘pesa’ and ‘m’ for mobile, began as a concept piloted by British telecom giant Vodafone as a corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiative in partnership with local service provider Safaricom. It was partly funded by DFID in Kenya in an attempt to facilitate financial access for micro-lenders and their clients. Pilot studies revealed that the application was in fact being used for general money transfers, and the application was redesigned. Essentially, Safaricom subscribers who also register with M-Pesa can transfer money between cell phone users, even if neither of them has a bank account. M-Pesa in its current form was launched in Kenya in April 2007, and it revolutionised the financial services landscape.

In 2006, before M-Pesa was launched, 25% of Kenyans had access to banking products. By 2014, this figure had jumped to 68%. Almost half of these users do not have a formal bank account, indeed, formal banking sector inclusion in Kenya remains as low at 23%. However, the M-Pesa platform performs the essential financial transactions: deposit and withdraw money, transfer money to other M-Pesa users and non-users, pay bills and purchase airtime. M-Pesa agents are as ubiquitous pavement airtime kiosks, whose owners have been duly trained and are incentivised by clipping a commission per M-Pesa transaction. This is the kind of distribution network that most ATM-driven banks can only dream about.

This context is not unique to Kenya. Small wonder that Sub-Saharan Africa is a global leader in the use of mobile money technology. On an average, 16% of the adult population actively use a mobile money product in the region; the global average is two percent. Of the 18 countries in the world that have more mobile money accounts than bank accounts, only one, Paraguay, is not in Africa. Here’s why.

On an average, 16% of the adult population in Sub-Saharan Africa actively use a mobile money product; the global average is two percent.

Visiting a physical bank branch can be time-consuming and expensive, in terms of transport costs to get there. Even with geographic access to a bank branch, the vast majority of the unbanked is not deemed to earn enough to warrant a bank account. However, in Kenya today, 43% of the population have a mobile phone — this figure jumps to 83% if one considers only Kenyans over 15 years of age. This immediately renders so-called mobile money products almost universally accessible. By way of example, Kenya today accounts for some 26.7 million M-Pesa accounts (and 33 million mobile phones), and has more active mobile money accounts than adults in its population.

There have been some surprisingly positive side effects in terms of financial empowerment of communities in rural areas, particularly women. According to one study, M-Pesa’s accessibility as a means of storing money greatly enabled women to save, as they would formerly have had to spend time and money to travel considerable distances to deposit money or access their savings. It kept funds safe from casual spending, either by themselves, or their husbands. This in turn increased community’s trust of and respect for them, as they were no longer forced to buy on credit. For many women, it created financial independence and privacy, as social conventions dictated that they had previously to rely on male relatives for access to funds.

According to one study, M-Pesa’s accessibility as a means of storing money greatly enabled women to save, as they would formerly have had to spend time and money to travel considerable distances to deposit money or access their savings.

It is no coincidence that M-Pesa’s wildly successful tagline was simply “Send Money Home.” Before the launch of M-Pesa, more than a quarter of Kenya’s population, usually rural women, were reliant on remittances for income, and 75% of the remittance providers would send cash informally, via travelling family members on public transport. By eliminating the time, cost and risk involved in this process, some estimates put the increase to household income that mobile money has facilitated at between five percent and 30%.

The average transaction size is around USD 33 and there is a cap of USD 500 on transactions in order to prevent the use of the platform for money laundering. Mobile money products are specifically designed to service cash transfers previously considered too small by banks to bother about. Half the transactions are for a value of less than USD 10. Indeed, M-Pesa accounts for just less than seven percent of national payments’ throughput value in Kenya, but more than two thirds of the transactions by volume.

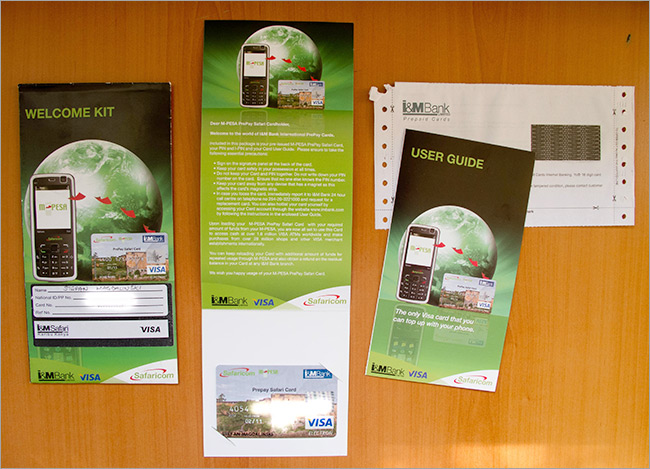

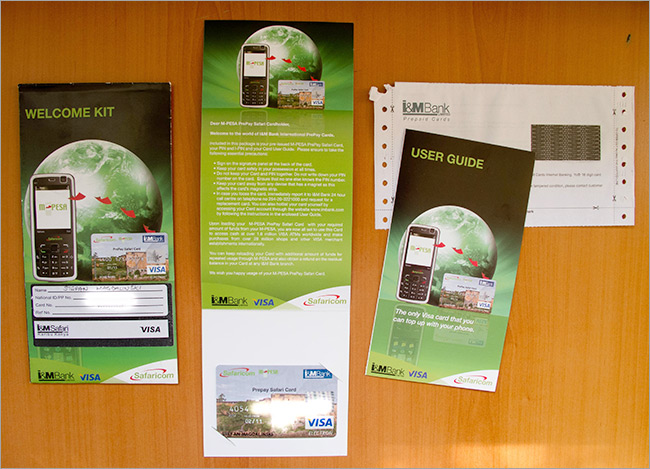

Photo: Stefan Magdalinski/CC BY 2.0

Photo: Stefan Magdalinski/CC BY 2.0

The truly fascinating aspect to mobile money in Kenya, is that it has become a digital platform from which other financial products can reach previously ignored segments of the population. Financial regulations in Kenya prevent Safaricom, the local M-Pesa service provider, from earning or paying interest on the M-Pesa money flows, as it does not hold a banking license. However, an innovative partnership with Kenya Commercial Bank has given rise to a sister product M-Shwari, through which M-Pesa account holders can open an interest-earning savings account via their mobile phone. Excitingly, mobile network operators, which can track the transaction history linked to mobile money accounts, essentially have the information to enable the construction of a credit profile — historically one of the primary barriers to credit for low-income individuals — thus allowing M-Shwari to offer short-term loans to its customers. The fact that M-Shwari has a non-payment rate of two percent over 90 days, despite lending to a segment of the population considered highly risky by conventional banks, is testament to the product’s success.

However, M-Pesa is not a financial panacea that can be copy-pasted to all lower-income countries. Vodafone learned this to its detriment. Stupendous success in Kenya rendered the mobile service provider a self-declared expert on mobile money in Sub-Saharan Africa. The product was launched with gay abandon in several other countries such as Tanzania, DRC, Uganda and South Africa, as has been less successful, largely because the company has not taken the time to understand the structural nuances and social norms that inform the context of the formally unbanked in these countries. After being lured by South Africa’s conservatively estimated USD 20 billion informal market, embarrassingly, after struggling for six years, M-Pesa withdrew from South Africa in June 2016, having only a million registered users, well under one tenth of which were active.

In hindsight, the outcome was predictable.

M-Pesa’s success in Kenya was predicated on the fact that there was a real market need given the country’s low rate of financial inclusion, with a relatively permissible regulatory environment.

South Africa by contrast, has one of Africa’s most (formally) banked populations with 75% of South Africans owning a bank account and as a result has a highly regulated environment. Furthermore, there were already several alternative products promoting rural financial access, such as agent banking. Many of South Africa’s retailers have astonishing rural distribution, and through which more than a third of South Africans now access their accounts.

The significance of M-Pesa and the mobile money products alike is the potential it holds for retail financial access in the developing world and the money to be made in doing so. As the trailblazer in this innovation space, Safaricom now generates a reported 10% of its revenue through providing a transactional banking platform for that segment of the population conventional financial institutions did not consider worth it to bank.

Their loss.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Photo:

Photo:  PREV

PREV