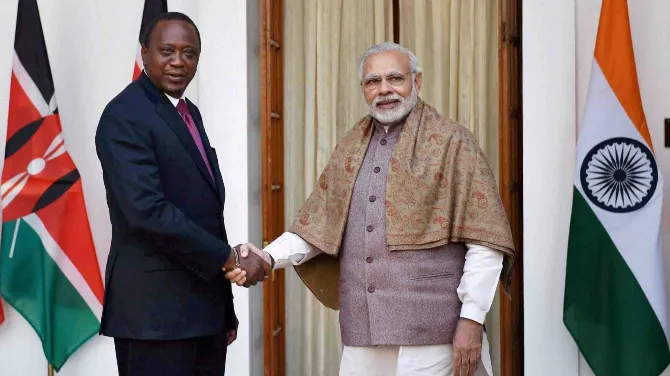

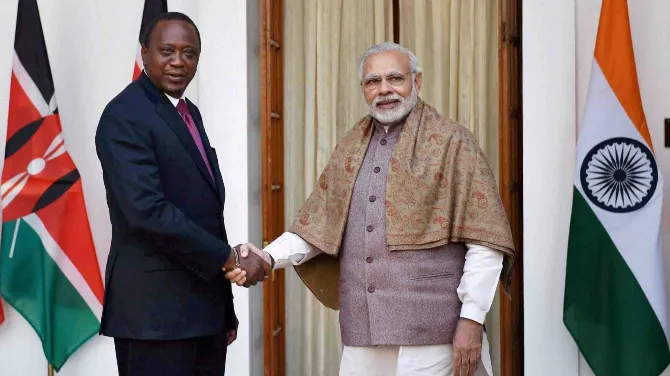

Source Image: PTI

Soon after India succeeded in its initiative of inviting the African Union (AU) to join the G20 in September, there were two state visits by African leaders. The first visit was by Tanzanian President Samia Suluhu Hassan in October which was followed by Kenyan President William Ruto’s visit on 4-5 December. This year is the 60th anniversary of diplomatic relations between India and Kenya, although relations have a millennial history.

Both Tanzania and Kenya were enthusiastic participants at the Voice of Global South Summits. Tanzania is a steadfast friend of India, an effective utiliser of development cooperation and among the largest beneficiaries of the lines of credit (LOCs). It is now India’s strategic partner and provides opportunities for Indian businesses. Kenya, on the other hand, has been an old partner of India, essentially based on people-to-people and business connections. Politically, Kenya has been the most aloof of the three East African countries Uganda, Tanzania, and Kenya. An Indian visit to Uganda is anticipated for the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) summit in January 2024.

Tanzania is a steadfast friend of India, an effective utiliser of development cooperation and among the largest beneficiaries of the lines of credit (LOCs). It is now India’s strategic partner and provides opportunities for Indian businesses.

The Ruto visit to India is significant in several aspects. This is the first visit by a Kenyan president in six years. PM Modi visited Tanzania and Kenya in 2016. The previous President Uhuru Kenyatta and former PM Raila Odinga, were both well inclined to India with good connections to the Indian diaspora. Ruto, deputy president under Kenyatta, had no known connection to India or the diaspora. He had not visited India officially until now.

In his first year in the presidency, he has made 38 foreign visits leading to domestic criticism that he is neglecting Kenya's diminishing economy. Ruto positioned himself as an outspoken leader of the African voice, particularly about climate and reform of the multilateral development banks. He chairs the AU’s Committee of African Heads of State and Government on Climate Change (CAHOSCC) and hosted the Africa Climate Summit in September. He repositioned Kenya, which was otherwise only known as the headquarters of an ineffectual United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). At COP28 in Dubai, he received praise for articulating the African voice, not depending solely on handouts, and looking for a constructive way out for Africa. This is akin to what India seeks and his position resonates with Indian G20 initiatives.

Until now, Kenya was not part of the International Solar Alliance (ISA). Now during the visit, Ruto’s climate interest led to Kenya joining the ISA and the Biofuels Alliance. Their accession to the Big Cats Alliance including joining the cheetah experiment in India and the Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure may emerge. This is a positive appreciation by Kenya of Indian initiatives.

India's relationship with Kenya has largely been economic. The Indian diaspora plays a major role. Kenya has the best economic ambience in the region. 60 Indian FDI projects are successful in Kenya. It is the hub of banking and manufacturing companies, which seek regional markets. Kenya's better economic management, market size, and rising educated middle class give it a pole position within the enlarged East African Community. Indian companies find Kenya a useful place to operate. India-Kenya trade is less than US$2.5 billion; most are Indian exports of petroleum products, pharmaceuticals, vehicles and engineering goods. Imports from Kenya are largely of soda ash and agricultural produce. Kenya is not a least developed country (LDC) and does not get the benefits of the Duty-Free Tariff Preference (DFTP)Scheme. It has, however, secured during the visit, access for its avocados to the Indian market.

India's relationship with Kenya has largely been economic. The Indian diaspora plays a major role. Kenya has the best economic ambience in the region. 60 Indian FDI projects are successful in Kenya. It is the hub of banking and manufacturing companies, which seek regional markets.

Kenya has traditionally had Indian banks like the Bank of India and Bank of Baroda spread across the country. Now, Kenya is going to host the representative office of Exim Bank of India. This office opened in 2010 in Ethiopia, which was then the largest beneficiary of Indian lines of credit (LOCs), and welcomed Indian banks. Since then, much has changed in Ethiopia, including civil war. Kenya, in contrast, is a beacon of stability. Therefore, it is wise for the EXIM Bank to move to Nairobi. It will be collocated with a host of local and foreign banks and importantly, with the Trade and Development Bank (TDB), the regional bank for the COMESA region. TDB uses EXIM LOCs for small and medium-sized enterprises This move should allow EXIM Bank of India to invest in eastern Africa and expand its debt and equity support for Indian companies. In a recent book, The Harambee Factor, a survey of Indian companies showed that Eastern Africa in general, and Kenya, in particular, were the prime targets of Indian companies seeking new FDI in Africa.

Unlike Tanzania, Kenya has been an FDI-led model of economic cooperation with India. It has not utilised grant projects allocated to it except for the Bhabhatron for cancer treatment. Projects allocated under IAFS I & II were not used. Kenya also did not join the Pan African e-Network Project (PAENP), which otherwise ran in 47 countries for a decade. Kenya rarely utilised LOCs because its attention was initially on Western countries and for the last two decades on China.

Earlier LOCs offered to Kenya generally lapsed except for a few used by the Industrial Development Bank of Kenya for two-step loans to Kenyan SMEs. It was only in 2016 that a US$29.95 million LOC to revive the RivaTex textile mills was accepted and quickly utilised. Now, there seems to be a change of attitude. Kenya sees the potential of collaborating with India, even by borrowing at higher rates, since Kenya is not an LDC or HIPC. Kenya requested a large LOC and has been offered US$250 million to enhance their agricultural sector. This is a well-thought-out proposition under Ruto, who focuses on the Bottom Up Economic Transformation Agenda (BETA) in which agriculture and the digital economy both are focal points. During the visit, Ruto brought three governors of counties with him where this project is likely to be implemented. They have focused on the modernisation and mechanisation of agriculture at the grassroots by utilising this LOC,

This is also important because the LOC system almost ebbed away over the last few years where countries offered LOCs had not finally signed up mainly due to debt stress. The Kenyan request for a LOC pumped new life into the LOC system. Now it remains to be seen whether the strict 2015 guidelines particularly on tendering and the monitoring of the decision-making by the EXIM Bank of India will allow this to fructify.

Traditionally education is an important link between India and Kenya. 3500 Kenyan students are in India, more privately than under scholarships. These scholarships have now increased from 48 to 80. Kenya’s utilisation of the ITEC program, the Raman science fellowships and agricultural fellowships is above average.

If the agricultural projects take off, they could lead to a further utilization of ITEC positions related to the project, to augment the capabilities and skills required for their success.

Though Kenya did not join the Pan African E network project, it has a consistent interest in virtual education. During the Ruto visit an agreement between IGNOU and the Kenyan Open University is a welcome sign. IGNOU will be challenged to grasp this opportunity and make it a commercial success. None of the Indian universities in the PANEP converted that opportunity to commercial levels.

Unlike Uganda and Tanzania, Kenya's defence engagement with India has not been a salient feature. It is not a buyer of Indian defence equipment. Kenya has avoided direct participation in India's Indo-Pacific and SAGAR strategies. However, during the current visit, the joint vision statement on maritime security is quite a step forward. It brings India and Kenya on a new path with regard to collaboration and cooperation on the Indian Ocean which unites us. The Indian and Kenyan views on the blue economy, HADR, and non-traditional threats have a commonality that may now be tapped. They envisage using the institutions and instruments that both are members of, like the IORA and the Djibouti Code of Conduct for plurilateral engagement. Kenya has participated in the India African exercise and military conclaves over the last two years. Now it may participate in the multilateral MILAN on India’s East Coast. This is perhaps one of the more salient outcomes of the Ruto visit.

There are some significant changes in Kenya's appreciation of India and these emerge through the Ruto visit. The agreements signed, the joint statement, and the joint vision statement on maritime security embody a more strategic ambience. Some rush to perceive Kenya loosening its Chinese strings, but that is premature. Kenya is seeking diversity in its partnerships and sees India as a credible partner at the present stage of international reordering. India’s Global South focus, successful leadership of the G20 and digital impact on welfare, all impress the Kenyan leadership who now look at a new framework to engage India.

Gurjit Singh has served as Indian ambassador to Gesrmany, Indonesia, Ethiopia, ASEAN, and the African Union. He is the Chair of CII Task Force on Asia Africa Growth Corridor (AAGC).

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV