-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

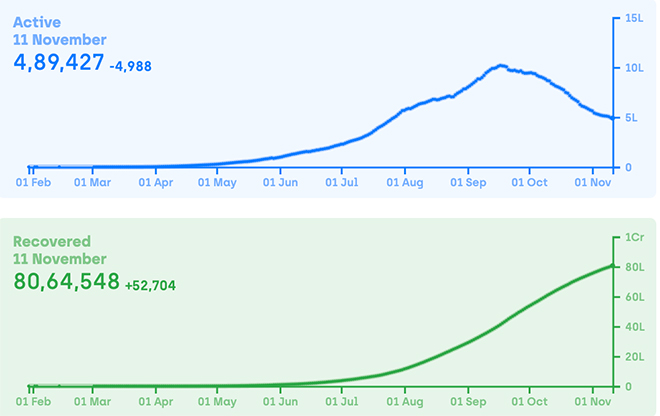

In India, after the national peak of just under a hundred thousand Covid19 cases per day in mid-September, daily positives seem to have settled at levels of about 45,000. The number of current active cases in India has fallen to under half a million (Graph 1), levels similar to the end of July. This corresponds to about six per cent of the overall recorded positive cases of Covid19 in the country till date. Even with daily testing numbers remaining at very high levels of more than a million per day, India’s weekly test positivity is under five per cent, the threshold suggested by the World Health Organisation to get out of lockdown. Clearly, India’s declining case numbers are not a function of testing anymore.

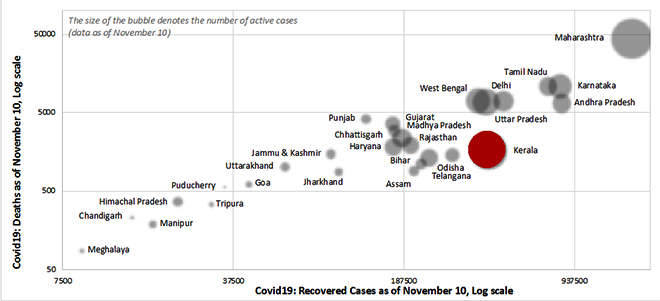

Still, a handful of states and territories show very high daily case numbers, like Kerala, Delhi, West Bengal, Maharashtra, Karnataka and Haryana. With the ongoing festival season, more states are feared to join this list. Despite booming Covid19 numbers, Kerala was praised by the Union government for keeping mortality levels admirably low. However, unofficial estimates show that around half the number of Covid19 deaths are being systematically kept out of the state’s death statistics.

Graph 1: Number of Active Cases in India

Source: https://www.covid19india.org/

Source: https://www.covid19india.org/

While India’s active cases are constantly on a decline, signifying a higher number of recoveries every day as opposed to new cases, Kerala has been an exception with a late surge. Kerala’s current status as one of the largest Covid19 hotspots in India – the state has around 80,000 active cases (Graph 2), when Maharashtra with about four times its population has over 90,000—is in sharp contrast to the state’s initial success in containing the virus which was celebrated the world over. Kerala’s test positivity has been consistently over 10%, one of the highest in the country, suggesting it has a long way to go.

Kerala’s surging case numbers in the last few months has resulted in Kerala being called a failure in dealing with the pandemic, a somewhat unfair categorisation aided also by the initial, overenthusiastic celebration of the “Kerala Model” of containment as some kind of silver bullet against Covid19.

Kerala’s surging case numbers in the last few months has resulted in Kerala being called a failure in dealing with the pandemic, a somewhat unfair categorisation aided also by the initial, overenthusiastic celebration of the “Kerala Model” of containment as some kind of silver bullet against Covid19. In many ways, the commentators who celebrated the great success of Kerala over the coronavirus were guilty of treating the first phase of a marathon as a separate sprint event, and to an extent, those who currently discard lessons from Kerala and term it a failure just because of a surge in cases may be indulging in the same mistake.

Graph 2: Covid19: Active Cases, Recovered and Deaths in the States with 1000+ Cases

Source: https://www.orfonline.org/covid19-tracker/

Source: https://www.orfonline.org/covid19-tracker/

Kerala was the first Indian state to report a Covid19 patient, as early as January this year. The rest of India started reporting cases in March. Learning from its early experience with Nipah, a much more fatal virus, Kerala’s health system had strict and effective protocols in place, and stuck to the time-tested strategy of early testing, case isolation and contact-tracing, combined with an alert community surveillance system backed with very strict lockdowns implemented with an iron hand by the police. Tens of thousands of people were in home quarantine, with compliance made possible via a mix of active involvement of the state apparatus, phone-based monitoring and citizens’ neighbourhood watch initiatives.

The state was remarkably successful in breaking the transmission chain till early August, when it had a manageable daily load of around 1,000 cases, and around 10,000 active cases.

Through these measures, the state was remarkably successful in breaking the transmission chain till early August, when it had a manageable daily load of around 1,000 cases, and around 10,000 active cases. Through early interventions, the state was able to keep the cases and deaths at very low levels—only about 80 patients had died of Covid19 till early August. However, six months of living under such strict conditions seems to have led to a ‘lockdown fatigue’, and during the Onam festival in August, people ventured out to meet friends and family and to go shopping. In parallel, political controversies around alleged cases of corruption had resulted in street protests across the state. All these factors contributed to rapid transmission of the coronavirus.

A media blitz around how Kerala ‘slayed coronavirus’ and similar rhetoric may have (ironically) contributed to people’s complacent attitude towards the virus. What followed was an unprecedented surge in cases across state, whereby daily case numbers crossed 10,000. Still, the number of recorded deaths were kept low in Kerala, and in the regular press briefings given by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, the state is mentioned as an example of good case management resulting in low mortality.

Strict containment measures in the state worked well for months; however, it also meant that infection-induced immunity was kept very low in the state. This is borne out by the fact that results of surveys conducted as late as end August showed Kerala’s seroprevalence at 0.8%, eight times less than the national average. In parallel, a spate of success narratives and global recognition for the deft handling of the Covid19 epidemic perhaps made Kerala’s authorities increasingly self-conscious in their handling of the epidemic. At the same time, labour-intensive containment measures like contact tracing—often by the police force—became unsustainable after months of consistent effort.

Harsh actions which kept infection at bay for many months, made sure that the actual epidemic—of the scale seen in most other states—started in Kerala about five months down the line compared to others.

In effect, harsh actions which kept infection at bay for many months, made sure that the actual epidemic—of the scale seen in most other states—started in Kerala about five months down the line compared to others. The inevitable community transmission was delayed in the state considerably, which explains Kerala’s trajectory of daily cases being substantially different from most other states: Delhi is nearing its third peak, while Kerala’s first peak was just a couple of weeks ago. With tens of thousands of migrants coming back every week from Covid19-ravaged countries, the situation was ripe for a breakout in August, when Onam festivities facilitated viral transmission.

However, the pressure on health authorities to keep the state’s status of a global “Covid19 success story” intact was immense. At this point in time, Kerala decided to redefine ‘success’ from one of containing virus, to one of preventing deaths: "In the end all that matters is how we reduce the mortality rate; how many lives we could save. That's our aim. Our mortality rate is still below 0.4 per cent. The mortality rate of 0.36 is the best among the world," Kerala’s Health Minister Ms K K Shailaja told the media.

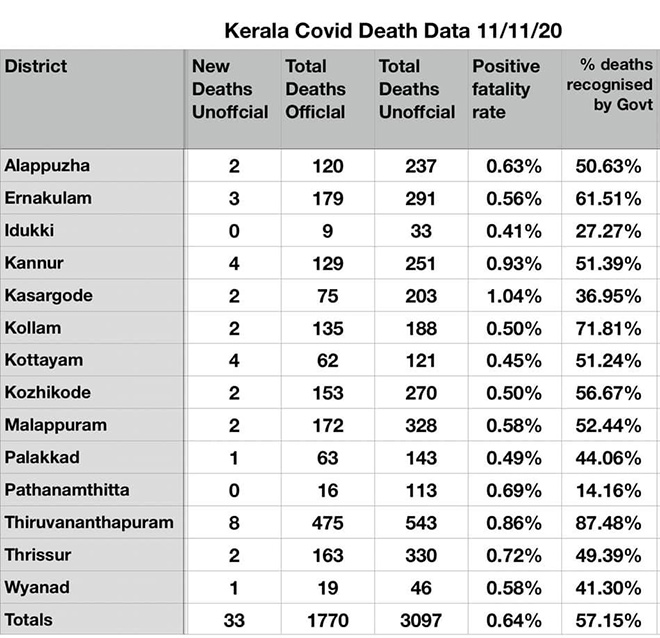

It is in this context that the systematic under-reporting of Covid19 deaths in Kerala needs to be examined. While state level health authorities claim that low levels of deaths are a direct result of careful clinical management, available data tell a completely different story. A group of volunteers has been painstakingly putting together district level death data from unofficial sources like newspapers from the beginning of the pandemic. Their findings are revealing. As Table 1 shows, till 11th November, Kerala has recognised only 57% of deaths as caused by Covid19, calling the rest ‘deaths by comorbidities’.

Table 1: Comparison of District-level Official and Unofficial Covid19 Deaths as on 11th November

Source: https://www.facebook.com/arun.nm/posts/4144928525522221

Source: https://www.facebook.com/arun.nm/posts/4144928525522221

The difference between Kerala and many other Covid19 hotspot states is that undercounting in Kerala has been conscious and systematic, and not because of systemic weaknesses. The state has, perhaps, the strongest surveillance capacity and even had a government appointed committee tell the health department that they are mis-categorising deaths. However, no major reconciliation of deaths has happened yet. The authorities seem to be convinced that by whatever means, the state should keep its reputation as a “Covid19 success story”. The irony is that even if all Covid19 deaths were to be counted, what Kerala would have achieved up until now in terms of mortality reduction would still be extraordinary.

The state level health officials actively hide Covid19 deaths, even when many district level authorities keep reporting real numbers. This is done by categorising a majority of Covid19 deaths as deaths due to comorbidities. Available data indicates that in order to avoid the media glare, most of the undercounting may have happened away from the state capital, Thiruvananthapuram, which also happens to be the biggest hotspot within the state. Pathanamthitta is a case in point, where according to the District Collector, there have been 101 Covid19 deaths till 11th November. However, state level authorities refuse to report these deaths to the central Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, terming most of these to be due to comorbidities. According to Kerala’s Directorate of Health Services, Pathanamthitta has had just 16 Covid19 deaths, as on 11th November.

In the politically charged atmosphere of the state, the Pinarayi Vijayan government is trying hard to distract the public's attention from multiple ongoing investigations around alleged scams by using its “Covid19 success story” like an Olympic medal.

In the politically charged atmosphere of the state, the Pinarayi Vijayan government is trying hard to distract the public's attention from multiple ongoing investigations around alleged scams by using its “Covid19 success story” like an Olympic medal. The Success/Failure metric that the media promotes, whereby a high number of recorded cases or deaths is inevitably defined as failure isn’t helping either. This flawed framework is endorsed even by the central ministry as evident from its regular press briefings where (selective) comparative global statistics are shown to convince the public how well we are doing and how bad the rest of the world is doing. Public accountability has become the unfortunate casualty as evidenced by Kerala’s experience, and the sense of complacency that such false death reporting brings about will have a severe impact on Kerala health system’s ability to fight the pandemic in the long run.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Oommen C. Kurian is Senior Fellow and Head of Health Initiative at ORF. He studies Indias health sector reforms within the broad context of the ...

Read More +