The Department of Economic Affairs in the Ministry of Finance released the 28

th edition of the

Status Report on India’s External Debt 2021-22 on 5 September. By the end of March 2022, India’s external debt had grown 8.2 percent to US$ 620.7 billion as compared to the previous year’s figure of US$ 573.7 billion. However, external debt as a ratio to GDP came down to 19.9 percent in March-end 2022 from 21.2 percent during the same period in 2021. Foreign currency reserves to external debt ratio have gone down marginally to 97.8 percent in March-end 2022 from 100.6 percent in the previous year.

While 53.2 percent of external debt is denominated in the US dollar, Indian rupee-denominated debt at 31.2 percent of the total is the second largest. The volume of long-term debt has been estimated at US$ 499.1 billion

–80.4 percent of the total. The short-term debt accounted for 19.6 percent of the total debt burden, at US$ 121.7 billion.

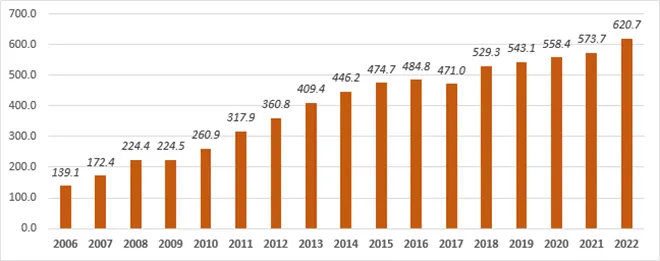

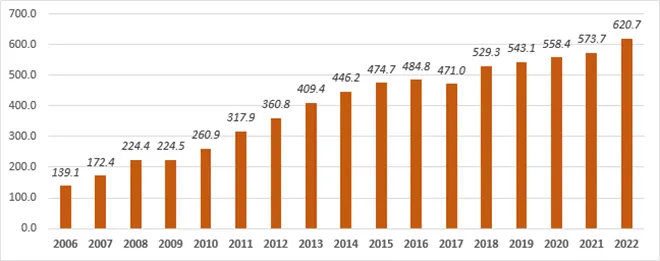

FIGURE 1: India’s external debt since 2006 (in US$ billion)

* The 2020 figure is revised estimate, 2021 is partially revised, and the 2022 figure is provisional.

* The 2020 figure is revised estimate, 2021 is partially revised, and the 2022 figure is provisional.

* Figures are taken in end-March.

Source: Reserve Bank of India

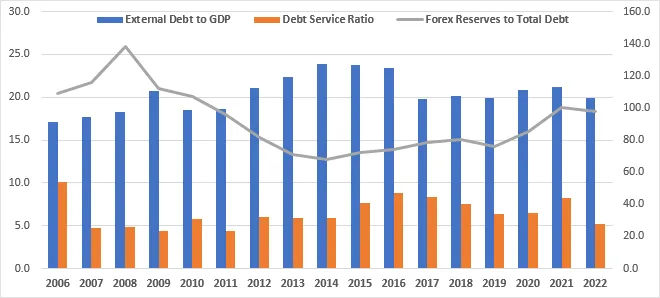

India’s external debt burden grew consistently in the last decade and a half. The absolute value of external debt was US$ 139.1 billion in 2006, and now it is at US$ 620.7 billion (

Figure 1). However, India’s GDP has also increased manifold in this period. As a result, external debt as a ratio of GDP remained at a sustainable level. India’s external debt to GDP ratio was 17.1 percent in 2006, then went upward to 23.9 percent in 2014 but subsequently has come down to 19.9 percent in 2022—same as the ratio in 2019 (

Figure 2).

As GDP increases the external debt component in the economy also increases. An increase in economic activity and investment is almost always fuelled by a rise in credit. A part of that credit may be sourced from the international financial markets. So, there is nothing unusual about external debt rising with GDP.

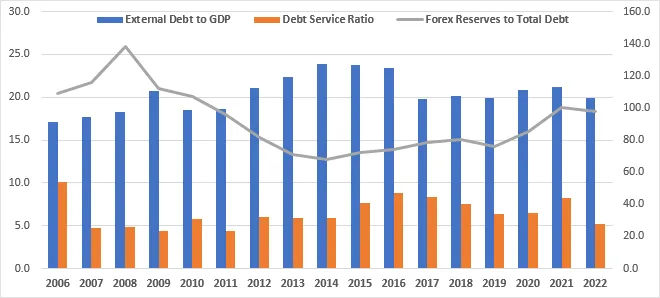

For debt repayment, a country needs to have adequate foreign exchange reserves. India’s foreign exchange reserves to total debt ratio were at a high of 138.0 percent in 2008. They dropped to 68.2 percent in 2014 but subsequently climbed back to 100.6 percent in 2021 before marginally decreasing to 97.8 percent in 2022 (

Figure 2). So, currently, foreign exchange reserves are adequate for debt repayment purposes.

A country’s

debt service ratio is that of debt service payments (both principal and interests) made by or due from a country to that country’s export earnings. India’s debt service ratio was 10.1 percent in 2006, it went down to 4.4 percent in 2011 and inched up to 8.8 percent in 2016, but the ratio is estimated to go down to 5.2 percent in 2022 (

Figure 2). Therefore, there is no immediate challenge to debt servicing for India.

FIGURE 2: India’s key external debt ratios since 2006 (in percent)

* The 2020 figure is revised estimate, 2021 is partially revised, and the 2022 figure is provisional.

* The 2020 figure is revised estimate, 2021 is partially revised, and the 2022 figure is provisional.

* Figures are taken in end-March.

* Forex reserves to debt ratios are measured in the secondary axis.

Source: Reserve Bank of India

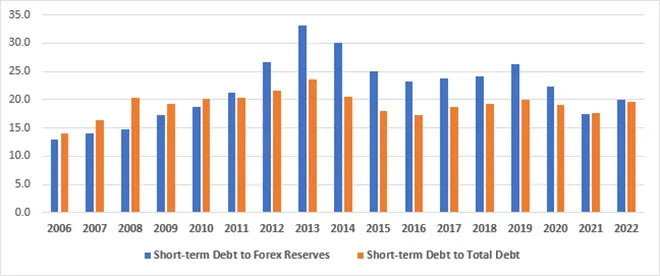

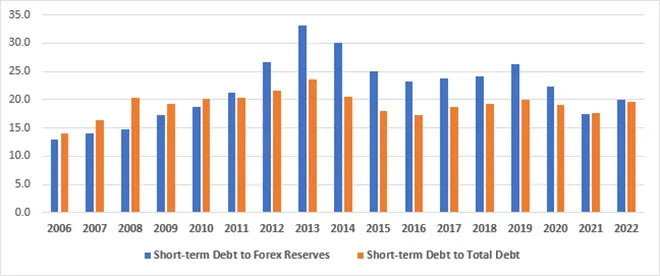

A large amount of short-term debt can potentially impair the ability of an economy to repay its external debt. A shorter maturity period of any loan reduces the flexibility of repayment for the borrower. In 2006, India’s short-term debt to forex reserves ratio was 12.9 percent and its short-term debt to total debt was 14.0 percent. Short-term debt to forex reserves and short-term debt to total debt increased to 33.1 percent and 23.6 percent respectively, in 2013. Subsequently, these ratios came down to 17.5 percent and 17.6 percent in 2021, before slightly going upwards to 20.0 percent and 19.6 percent respectively in 2022 (

Figure 3). Going by this debt indicator also, there is no immediate risk.

FIGURE 3: India’s short-term external debt ratios since 2006 (in percent)

* The 2020 figure is revised estimate, 2021 is partially revised, and the 2022 figure is provisional.

* The 2020 figure is revised estimate, 2021 is partially revised, and the 2022 figure is provisional.

* Figures are taken in end-March.

* Forex reserves to debt ratios are measured in the secondary axis.

Source: Reserve Bank of India

The composition of debt has also changed, compared to the earlier times. Now, non-government debt constitutes the bulk of India’s external debt. Out of the total debt, the government’s share is around 21 percent in 2022 whilst the non-government share is around 79 percent. External debt of the non-financial corporations is the highest among different categories in 2022—at US$ 250.2 billion (

Table 1).

| TABLE 1: Government and non-government external debt (US$ billion, unless indicated otherwise) |

|

End-March |

|

2019 |

2020 (R) |

2021 (PR) |

2022 (P) |

| A. Government Debt (I+II) |

103.8 |

100.9 |

111.6 |

130.8 |

| (As percentage of GDP) |

(3.8) |

(3.8) |

(4.1) |

(4.2) |

| I. External Debt on Govt. Acc. Under External Assistance |

68.8 |

72.7 |

84.5 |

86.7 |

| II. Other Govt. External Debt# |

35.0 |

28.1 |

27.1 |

44.1 |

| B. Non-government Debt |

439.3 |

457.5 |

462.0 |

490.0 |

| (As percentage of GDP) |

(16.1) |

(17.1) |

(17.1) |

(15.7) |

| I. Central Bank |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

| II. Deposit-taking Corporations, except Central Bank |

164.3 |

158.2 |

160.8 |

158.7 |

| III. Other Financial Corporations |

31.2 |

40.7 |

55.2 |

53.2 |

| IV. Non-financial Corporations |

226.4 |

235.7 |

220.7 |

250.2 |

| V. Households & non-profit institutions serving households |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| VI. Direct Investment: Inter-company lending |

17.1 |

22.7 |

25.2 |

27.7 |

| C. Total Debt (A+B) |

543.1 |

558.4 |

573.7 |

620.7 |

| (As percentage of GDP) |

(19.9) |

(20.9) |

(21.2) |

(19.9) |

|

* R = Revised, PR = Partially Revised, P = Provisional

# Other government external debt includes defence debt, investment in treasury bills/government securities by FPIs, foreign central banks and international institutions, and SDR allocations by the IMF.

Source: Reserve Bank of India |

Though there is no immediate reason for concern, India cannot afford to be complacent about its external debt amidst the current global economic turbulence. First of all, the Indian rupee has depreciated sharply vis-à-vis the US dollar in recent times. This can affect the future accumulation of external debt and also can increase the future repayment burden. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) periodically intervenes to arrest the fall of the rupee, and that can reduce the foreign exchange reserve.

Second, the Indian economy is also going through a phase of inflation. Prolonged inflation remains a risk as the RBI would then further increase the interest rates. That may slow down the growth, resulting in a higher ratio of external debt to GDP in future.

Third, as external debt risks shift from the government sector to the non-government sector, the repayment risks may also increase in future. In a situation of debt distress, the government can always negotiate with international lenders to avail concessional facilities, and extend and roll over repayment liabilities. However, those avenues are not available to the private sector and banks. This risk element is needed to be factored in.

Fourth, the stagflation threat looms large over the major economies of the world. That can sharply affect future demands for Indian exports. If export earnings go down in future, they can adversely affect the debt service ratio.

Last but not the least, the US Federal Reserve Bank is likely to continue increasing domestic rates to combat inflation. That may result in capital flights in emerging economies. Any such occurrence in India can reduce the foreign exchange reserves. That also remains a downside risk.

Indian policymakers should remain vigilant and monitor all these factors on a real-time basis,—this will be very crucial to immediately mitigate external risks arising out of any new global economic and financial development.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

The Department of Economic Affairs in the Ministry of Finance released the 28th edition of the

The Department of Economic Affairs in the Ministry of Finance released the 28th edition of the

PREV

PREV