-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The fall in prices and the strengthening of international financial linkages will allow India to attain a current account surplus

India’s goal to become a US$ 5-trillion economy with the underlying objective of becoming a developed nation by 2047, has picked up a renewed pace after the pandemic. With integration into Global Value Chains (GVCs) and digitisation of the economy, India has established itself as a global player. The G20 Presidency came to India at the perfect time, allowing it to promote its ideas and unite the Global South to reform the principles of development and international cooperation in a post-pandemic, geopolitically segregated world.

Trade is one of the first forms of cooperation that countries enter into, driven by their national needs and the underlying principle of comparative advantage. Undergoing centuries of transformation, international trade has now metamorphosed into a holistic domain that has wide-ranging implications for all aspects of development—sustainable development, economic growth, technological progress, inequality, and most importantly, the environment.

Trade is one of the first forms of cooperation that countries enter into, driven by their national needs and the underlying principle of comparative advantage.

Given the drastic consequences of trade, an exploration of the current trade statistics and trends in India is warranted. The transformation of Indian services and the rising dependency on crude oil have jointly laid out the trajectory of India’s current account—rendering the possibility of a surplus uncertain.

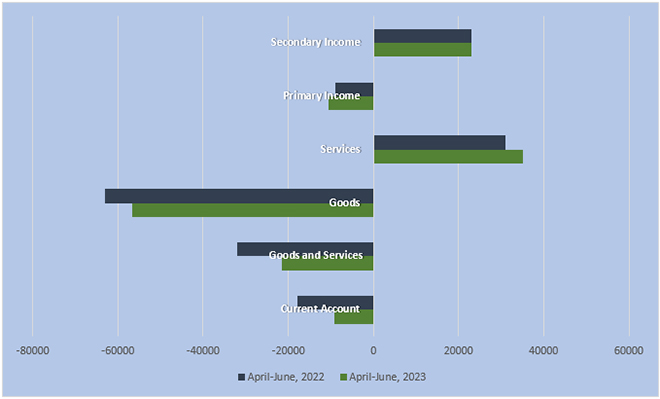

The Reserve Bank of India has recently published the developments in the Indian Balance of Payments for the first quarter of the fiscal year 2023-24. The current account deficit for April to June 2023 stood at US$ 9.2 billion, down by almost 50 percent from US$ 17.9 billion for the same quarter in the previous year. However, the deficit has grown wider from US$ 1.3 billion in the previous quarter. The widening of the deficit from the past quarter can be attributed to a marginally higher trade deficit in merchandise (by US$ 4.01 billion) and a marginally lower surplus in invisibles (services, transfers, and incomes).

Closer scrutiny of the invisibles account reveals that the net receipts from services went down from US$ 39.07 billion to US$ 35.1 billion every quarter. Similarly, net transfers declined from US$ 24.76 billion to US$ 22.86 billion. However, net outflow of income reduced from US$ 12.6 billion to US$ 10.6 billion. While the fall in services exports resulted primarily from the slowing down of exports of computer, travel, and business services, the reduction in net transfer receipts can be explained by the fall in net remittances from Indian individuals employed abroad. The quarterly fluctuation of US$ 7.9 billion in the current account deficit can be explained by these developments.

India’s trade deficit for intermediate goods and capital goods for the first quarter of the fiscal year 2023-24, stand at US$ 27 billion and US$ 21.39 billion respectively.

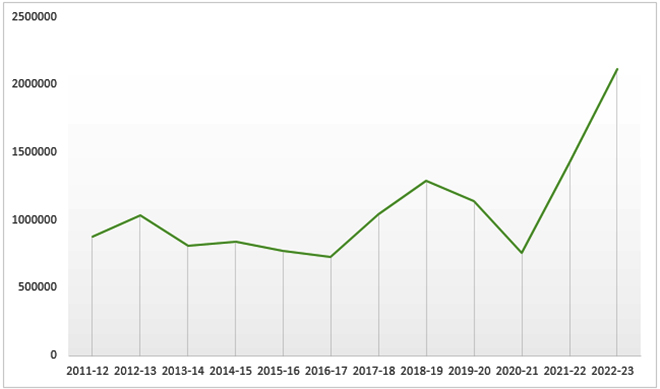

The trade balance usually exhibits an annual cyclical trend with the trade deficit hitting the bottom of the trough around December every year. This highlights the need for a year-on-year comparison of the current account figures. India’s trade deficit shrunk significantly in 2020-21 due to supply chain disruptions and an overall reduction in demand during the pandemic. However, there was a significant bounce back in the trade deficit in the following years. While the country ramped up production to meet the increasing export demand, there was a far greater jump in imports. Crude petroleum which accounts for almost 20 percent of the country’s total import bill, recorded major price hikes during and in the aftermath of the pandemic, which was further exacerbated by the Russia-Ukraine crisis. India’s trade deficit for intermediate goods and capital goods for the first quarter of the fiscal year 2023-24, stand at US$ 27 billion and US$ 21.39 billion respectively. Electrical machinery and equipment which reserve a high share in imports (around 10 percent) have not experienced any significant departure from that range following the pandemic.

Figure 1: India’s Trade Deficit (in Crores INR)

Source: RBI

To investigate the stark 50 percent decline in the trade deficit from the first quarter of 2022-23 to the first quarter of 2023-24, the underlying components have to be compared. The trade deficit in goods declined by around US$ 6.5 billion (10.3 percent) while the surplus in services widened by over US$ 4 billion (12.9 percent). This was mostly driven by an increase in the exports of services. The sectors responsible for this boost include – manufacturing services, transport services, construction services, financial services and telecommunication, information, and computer services. However, net investment income outflow increased by almost US$ 2 billion, indicating the returns generated by India on foreign investment.

Figure 2: Components of Current Account

Source: RBI

While the year-on-year trend is quite satisfactory for India, it is still a net importer. It is known that trade in goods is what weighs heavy on the current account’s debit scale – deeming an inspection of India’s commodity-wise trade balance necessary. Ranked in terms of highest value of imports, the top five commodities are – crude petroleum; coal, coke and briquettes; gold; petroleum products; and electronic components. On the other hand, the five most exported commodities are—6petroleum products; drug formulation, biologicals; pearls, precious and semiprecious stones; telecom instruments; and iron and steel.

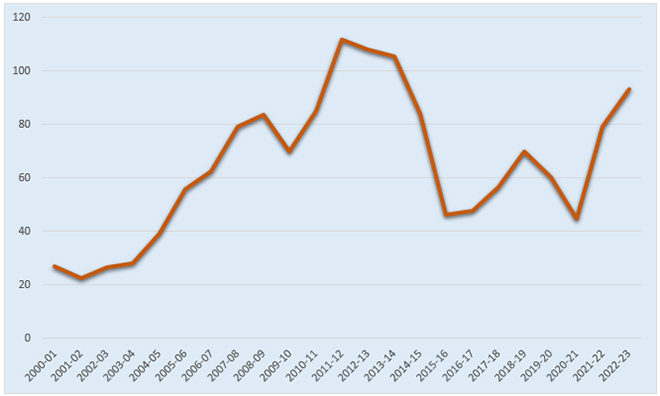

What puts a disproportionate burden on India’s trade balance is the import of petroleum. The important dependency on crude oil averages around 87 percent (on petrol, oil and lubricants basis), i.e., around 87 percent of the domestic consumption is sustained via imports. High-speed diesel (HSD) and petrol (motor-spirit) are the major drivers of domestic demand and hold the greatest share in the domestic production of petroleum products. Crude oil prices are on the rise as a result of sustained supply cuts and are expected to worsen with a widening supply shortage in the upcoming quarter. This will put exorbitant pressure on India’s current account and further widen the goods trade deficit. However, India’s total crude oil and condensate production exhibited a growth of 2.1 percent which will provide some relief by adding to India’s increasing share in export of petroleum products.

Figure 3: Crude oil price of Indian Basket (US$ per bbl)

Source: Petroleum Planning and Analysis Cell

With respect to principal commodities, India has the greatest trade deficit in vegetable oils (around US$ 5 billion). The import of vegetable oils, comprising both edible and non-edible oils, has increased by 33 percent in August 2023 from 1,401,233 to 1,866,123 tons in August 2022. Besides a deficit in monthly rainfall, the import demand was driven by a drop in domestic oil prices coupled with low import duties. However, domestic stocks are much higher at 3.735 million metric tonnes, expected to reduce the import bill in the current quarter. On the flipside, Russia and Ukraine are the fifth and seventh largest suppliers of oil for India, keeping the supply chain under pressure.

Despite high merchandise imports, India has a robust services trade surplus. Driven mostly by its exports of software and business services, this surplus is the key to balancing India’s current account and even moving towards a surplus. Based on the latest figures, at US$ 28.7 billion, services exports are up by 8.4 percent in August 2023 from August 2022. With a projected growth rate of 9.1 percent, the services sector has significant potential to contribute to national exports and balance out the trade deficit in goods.

Table 1: India’s Current Account Composition in 2022-23

| Item | Q4 | Q3 | Q2 | Q1 |

| 1 CURRENT ACCOUNT | -1,356 | -16,832 | -30,902 | -17,964 |

| 1.1 MERCHANDISE | -52,587 | -71,337 | -78,313 | -63,054 |

| 1.2 INVISIBLES | 51,231 | 54,505 | 47,411 | 45,090 |

| 1.2.1 Services | 39,075 | 38,713 | 34,426 | 31,069 |

| 1.2.1.1 Travel | 747 | 1,213 | -1,764 | -1,593 |

| 1.2.1.2 Transportation | -135 | -652 | -1,809 | -1,931 |

| 1.2.1.3 Insurance | 369 | -13 | 170 | 405 |

| 1.2.1.4 G.n.i.e. | -163 | -97 | -36 | -37 |

| 1.2.1.5 Miscellaneous | 38,256 | 38,262 | 37,865 | 34,225 |

| 1.2.1.5.1 Software Services | 34,370 | 33,541 | 32,681 | 30,692 |

| 1.2.1.5.2 Business Services | 5,945 | 6,073 | 5,178 | 3,448 |

| 1.2.1.5.3 Financial Services | 790 | 657 | 514 | 146 |

| 1.2.1.5.4 Communication Services | 341 | 514 | 403 | 522 |

Source: RBI

The service sector is driving the GDP growth in the country while employing a relatively lower share of the population. The Digital India and Startup India initiatives have integrated the Indian economy into GVCs, increasing India’s share in global commercial services. India has also leveraged its rich and skilled talent pool of information technology workers to exponentially grow the digital sector. The growing financial sector also has scope to absorb new talent and add to the services-led growth. Given the internationally competitive labour costs in the country, the growth of the service sector will translate into a concomitant stimulus to exports.

While India’s current account has shown a year-on-year improvement, the country is yet to experience a current account surplus. However, with the growing share of India’s services exports, a current account surplus can now be envisaged. Although goods import bills will rise and at best, moderate in this fiscal year, services growth is expected to continue. A gradual global stabilisation with cooling down of prices and strengthening of the international financial linkages will allow India to attain a current account surplus. The road ahead is marked with geopolitical contingencies but domestic initiatives to stimulate production will ameliorate the country’s import dependency and allow for a balanced trade environment.

Arya Roy Bardhan is a Research Assistant with the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy at the Observer Research Foundation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Arya Roy Bardhan is a Research Assistant at the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy, Observer Research Foundation. His research interests lie in the fields of ...

Read More +