-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Replicating the success of Gujarat’s gas market across the country will be difficult but not impossible

This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

The share of natural gas in Gujarat’s primary energy mix is about 23 percent, close to the global average of 24 percent and four times the share of gas in India’s primary energy basket. Gujarat has the most extensive gas pipeline network in the country with over 3370 kilometres (km) of main lines that accounts for about 20 percent of gas pipelines of length 21,102 km in the country. Gujarat’s per capita natural gas consumption at 191 kgoe (kilogram oil equivalent) is 400 percent higher than the national average of 39 kgoe. Consumption of natural gas of 11,667,095 SCMD (standard cubic metres per day) through CGD (city gas distribution) by Gujarat in the first half of 2023 accounted for roughly 34 percent of total CGD consumption, the highest in the country. In 2022, Gujarat had the highest number of CNG (compressed natural gas) stations accounting for over 19 percent of total CNG stations in the country, the highest number of domestic PNG (piped natural gas) connections accounting for about 27 percent of the total, the highest number of commercial PNG connections accounting for 59 percent of the total and the highest number of industrial PNG connections accounting for 39 percent of the total. Gujarat has the second largest number of CNG vehicles with over 27 percent of the total at the national level after Delhi NCR which had a share of 37 percent.

The success of Gujarat’s gas industry can be traced to the discovery of gas in Gujarat in the 1960s. This geographic proximity to gas supplies along with the enthusiasm of the Government of Gujarat to enlist industrial consumers with favourable prices which in turn led to investment in an extensive gas pipeline network was critical for the success of the gas industry in Gujarat.

Proximity to Supplies

The Oil and Natural Gas Commission (ONGC) discovered oil in the Cambay basin, Gujarat in 1958 and in Ankleshwar, Gujarat in 1960, just a few years after ONGC was set up. In fact, ONGC began exploration in Gujarat only after Oil India Limited (OIL) which was developing oil discoveries in Digboi in Assam in 1889 refused to work in Gujarat. Since ONGC’s front-end activity was exploration, the discipline of geology enjoyed great prestige in the early years and was central to strategic planning in the company. This led to discoveries in regions that were not thought to be attractive petroleum prospects by mature oil companies. The first major oil-find of ONGC in Ankleshwar located about 80 km south of Vadodara and nearly 160 km south of Khambhat was so productive that, the Prime Minister of India Jawaharlal Nehru called it a ‘fountain of prosperity’. With Ankleshwar, Gujarat became one of the earliest oil & gas producing states in the country. Many oil & gas discoveries followed and now Gujarat receives natural gas from six gas producing areas in Ahmedabad, Mehsana, Kadi, Kalol, Ankleshwar and Gandhar. Besides, Gujarat also receives offshore gas from Bassein field off the Mumbai coast and other satellite gas fields amounting to 40 percent of gas produced in India. The LNG (liquified natural gas) import capacity of 42.7 million tonnes per annum (MTPA) in Gujarat accounts for more than 64 percent of total LNG import capacity in India but in terms of actual imports LNG terminals in Gujarat account for over 95 percent of total gas imports into India.

Investment in Infrastructure

All countrywide major gas pipelines originate from the coastal locations of Gujarat. Besides, gas companies developed smaller pipelines from gas producing fields to specific consumers in Gujarat. Gujarat is the only state where the gas pipeline network is operated by more than one player, GAIL (Gas Authority of India Ltd), GSPL (Gujarat State Petronet Limited) and Gujarat Gas Limited (GGL). GAIL primarily serves consumers who have been allocated natural gas by the Ministry of Petroleum & Natural Gas (MOPNG) with several customers connected on HVJ (Hazira-Vijaipur-Jagdishpur) Pipeline, DVPL (Dahej-Vijaipur) and DUPL (Dahej-Uran-Panvel) pipelines. GSPL is the nodal pipeline agency in Gujarat with the mandate to set up a gas grid operating on a common carriage basis. GSPL pipelines serve consumers in the Hazira, Vapi, Halol, Bharuch, Vadodara, Ahmedabad, Morbi, Rajkot, Jamnagar, Mehsana, Himmatnagar & Kutch regions. The pipeline obtains gas from the GSPC (Gujarat State Petroleum Corporation) owned onshore gas fields in Hazira. The network also obtains gas from Cairn at Mora from its Suvali gas complex, imported gas from Petronet and Hazira LNG terminals and domestic gas from fields such as the Panna-Mukta and Tapti (PMT) and ONGC Olpad fields. GSPL pipeline network is connected to the East West Pipeline that transports gas from KG D6 field in Andhra Pradesh to Gujarat at Attapardi (Vapi) and Bhadbhutt (Bharuch).

Consumer Friendly Pricing

One of the earliest consumers of natural gas produced in and around Gujarat was the Gujarat state electricity board, whose Dhuvaran Project used the gas for power generation. Though this was seen by experts as a gross misuse of the gas and waste of a valuable natural resource (as opposed to using the gas that was rich in higher hydrocarbons for fertiliser production in the Baroda fertiliser plant which was burning naphtha from the Koyali refinery) burning gas for electricity generation continued as it was thought to be a cost-effective substitute for coal which had to be transported across thousands of kilometres. It was the 1960s and gas was a relatively new form of energy which initiated a debate over how to price natural gas for consumers such as the Gujarat state electricity board. Speaking on behalf of the electricity board, the state fertiliser company and smaller private companies that were potential users of gas, the Gujarat government demanded a price of INR 0.02-0.03 per cubic metre (m3) much lower than of the INR 0.08-0.10/m3 that ONGC wanted. The argument made by the government was that Gujarat had suffered on account of its great distance from coal mines and that it should be allowed to benefit from a new local source of energy. The price should, the government demanded, be fixed on a cost-plus basis. The government of Gujarat also cited the far lower price of INR 0.009/m3 charged by OIL (Oil India Ltd) in Assam and challenged the substitution principle that pegged the gas price to the prices of naphtha and fuel oil. The government of Gujarat also noted that being associated with gas (produced along with more valuable oil) the cost of gas production was negligible for ONGC. The dispute between ONGC & the government of Gujarat ended in arbitration and the price of INR 0.05/m3 awarded was closer to the price demanded by the Gujarat government on behalf of consumers. This price was questioned by economists who argued that ONGC must be run on a commercial basis and the development of Gujarat need not be subsidised by ONGC, a public corporation. In the absence of direct competition between fuels, the economists pointed out, the rational price of a fuel must bear some relation not only to the investment made on it but to the price of the next most easily available fuels (which were naphtha and fuel oil). But gas pricing settled at a level that favoured consumers at the expense of the producer, ONGC. Lack of competitive parity, in relation to other fuels and alternative end-uses, has for long distorted fuel policy in India. The error was compounded in natural gas and it continues till today. Domestic gas production (ONGC and other private sector producers) is penalised with regulated low prices. But in the early years, low prices relative to substitutes such as coal and fuel oil boosted consumption of natural gas in Gujarat. It is very unlikely that competitive pricing of natural gas comparable to substitutes would have created a vibrant gas market in Gujarat.

Expansion of Distribution

Gujarat Gas Limited (GGL) was incorporated under the name of Gujarat Amico Chem Limited by promoters Mafatlal Fine Spinning & Manufacturing Company Limited and Gujarat Industrial Investment Corporation (GIIC) in the 1980s to distribute gas production by ONGC from fields in Gujarat. GGL was so optimistic about the prospects for gas distribution that it signed an agreement with a Qatar based subsidiary of Enron for importing and transporting LNG for a power plant. In the 1990s, British Gas acquired a stake in GGL which was divested in the 2010s. Today, GGL is India's largest city gas distribution (CGD) player with presence spread across 22 districts in Gujarat and union territory of Dadra Nagar Haveli and Thane which includes Palghar district of Maharashtra. The company has India's largest customer base in major user segments. In 2015, GGL executed a gas purchase contract for regasified LNG with GSPC (Gujarat State Petroleum Corporation). In 2016, the PNGRB (Petroleum and Natural Gas Regulatory Board) granted authorisation to the company to lay, build, operate or expand CGD networks for the geographical area of Amreli, Baruch, Dahod Panchmahal, Anand and Ahmedabad districts in Gujarat. As per the provisions of the PNGRB, GGL was granted 300 months of infrastructure exclusivity valid up to May 2041 and 60 months of marketing exclusivity valid up to 26 May 2021 for the CGD network. GGL’s projects are almost entirely based on its own know-how and technology and indigenously available plant and equipment. This has minimised project cost and consequently reduced the cost of distribution to a level lower than that of other existing and planned gas distribution projects.

Issues

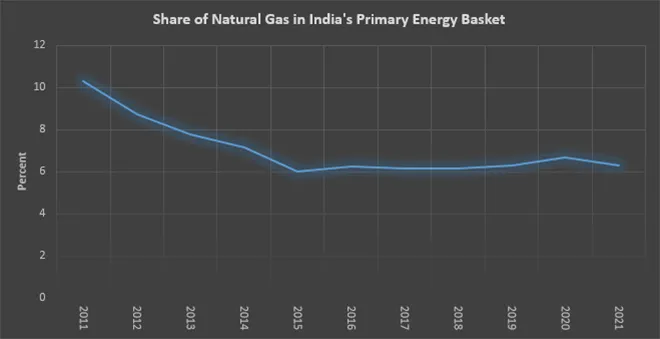

The share of natural gas in India’s primary energy basket (not including biomass) has fallen from about 10.3 percent in 2011 to 6.3 percent in 2021, roughly the same level as in 2019 which was last pre-pandemic year. The goal of making India a “gas-based economy” by increasing the share of natural gas in India’s primary energy basket to 15 percent is likely to remain a challenge. Even when critical drivers such as security of supply, low prices relative to alternatives and investment in pipeline infrastructure were in place, the development of a gas market in Gujarat took nearly five decades. This was the case even in much larger and more transparent gas markets in the USA and Europe. In the case of India, security of domestic supplies is uncertain. Though there is a liquid global market for LNG, there is uncertainty over price especially in comparison to alternatives such as domestic coal. Investment in infrastructure is progressing but there is much ground to cover. Overall, replicating the success of Gujarat’s gas market across the country will be difficult but not impossible.

Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy, 2011 to 2022

Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy, 2011 to 2022

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Akhilesh Sati is a Programme Manager working under ORFs Energy Initiative for more than fifteen years. With Statistics as academic background his core area of ...

Read More +

Ms Powell has been with the ORF Centre for Resources Management for over eight years working on policy issues in Energy and Climate Change. Her ...

Read More +

Vinod Kumar, Assistant Manager, Energy and Climate Change Content Development of the Energy News Monitor Energy and Climate Change. Member of the Energy News Monitor production ...

Read More +