-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Although India pledged to end gender disparities in its financial markets, however, studies show otherwise.

Advancing economic equity from a gendered perspective can lead to promising outcomes, contributing to economic growth with far-reaching implications for social development. Promoting higher economic participation amongst women can introduce new actors in labour markets making them more competitive, leading to productivity gains, and incentivising additional investments in physical capital—all leading to income growth. Moreover, the economic empowerment of women can also lead to socio-economic advancements with improved access to basic needs such as food and nutrition, healthcare, and education for women and girls, indicating overall progress along SDG 5 (gender equality). Studies have shown that for working women in emerging market economies (EMEs), investments in nutrition, healthcare, and education expenditure occupy 90 percent of their total earnings. Despite contributing to these additional opportunities—income inequality amongst men and women remains stark. Globally, on average, women continue to be paid 23 percent less than their male counterparts for the same work. For India, the picture appears even grimmer, with women being paid 34 percent less than men.

Studies have shown that for working women in emerging market economies (EMEs), investments in nutrition, healthcare, and education expenditure occupy 90 percent of their total earnings.

Besides the persisting wage gaps, gendered segmentation of labour markets has often hindered economic participation amongst women, ultimately feeding into the existing inequalities. In India, the battle for gender parity in labour force participation has been an uphill climb as resounded by the Global Gender Gap Report of 2021—with its female workforce confronting one of the largest gender gaps in economic participation and opportunity. Over the last decade, female labour force participation in India has declined from 23 percent (in 2012) to 19 percent (in 2021). No doubt, these income inequalities also serve to accentuate disparities in asset ownership and wealth inequalities among men and women. Several social security schemes have been launched in the past to address these economic inequalities and their impact, specifically targeting the poor and other marginalised groups. However, they have often failed to engage adequate women participation.

In fact, in an attempt to universalise social security benefits for the Indian population, the Government of India (GOI) announced a trinity in Budget 2015-16 focusing on pensions, life insurance, and risk insurance. The Pradhan Mantri Jeevan Jyoti Bima Yojana (2015) was launched with the aim to create a social security system for the poor and underprivileged in the age group of 18–50 years but the programme has not seen effective women’s participation. Similarly, Pradhan Mantri Suraksha Bima Yojana (2015), intended to provide an insurance scheme for the poor and underprivileged, has only 41.5 percent of enrolled women beneficiaries. Even in the case of direct transfer schemes like the Atal Pension Yojana (APY) (2015), which primarily targets the unorganised sector in India to provide government-backed pensions, only 44 percent of women are covered under the scheme.

Several social security schemes have been launched in the past to address these economic inequalities and their impact, specifically targeting the poor and other marginalised groups.

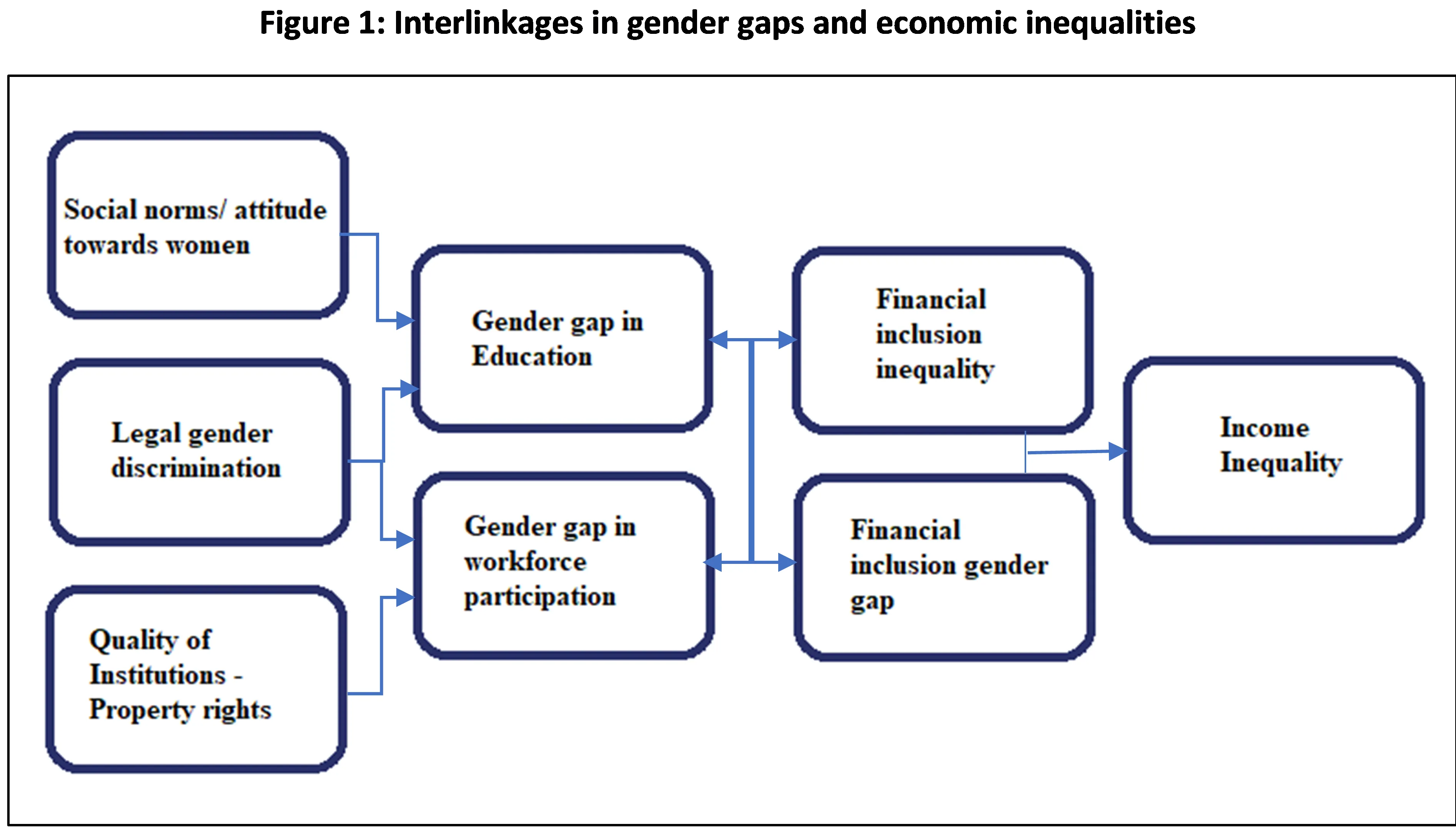

Against this backdrop, the inclusivity of financial markets becomes even more critical for reductions in economic inequalities amongst men and women. Gender gaps in access and utilisation of financial products can affect economic inequalities, directly and indirectly, often hindering access to productive assets and limiting opportunities for business expansion in the short term, and perpetuating gender gaps in education and labour force participation in the medium and long run. Women’s inclusion in financial markets can enhance their ability to engage in income-generating livelihood activities increasing their social capital in households and communities. Providing women with efficient financial tools for asset creation, portfolio diversification and risk management can lead to women’s empowerment and poverty reduction.

Source: Aslan et. al. (2017)

Source: Aslan et. al. (2017)

While India pledged to close gender disparities in its financial markets, making them inclusive by implementing the Denarau Action Plan, progress on actual outcomes has been lagging. The rise in Jan Dhan bank accounts under the Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) has expanded access to financial services and enhanced the financial independence of the Indian masses. Among these, the percentage of women in India who reported owning an account at a bank or any other financial institution stood at 77 percent in 2017. The All India Debt and Investment Survey (AIDIS) found that almost 81 percent of women across India had deposit accounts in banks. While the gender gap in account ownership decreased, the gaps in the usage of these accounts remained high. In many cases, while women own personal accounts, they often do not access them regularly. According to reports, 55 percent of women still don’t actively use their PMJDY accounts. The slow adoption of digital financial services by Indian women can be attributed to the large gender gaps in digital access and usage. Compared to men, 20 percent less women own personal mobile phones, and internet usage is 50 percent lower. With only 14 percent of Indian women having access to smartphones, the use of digital financial services by women is substantially affected.

However, structural issues such as large gender gaps in asset ownership, persistent unemployment, low wages, limited years of schooling, time investments in unpaid care work, safety concerns, and socio-cultural constraints pose major obstacles to women’s financial inclusion. The lack of collateral makes women high-risk borrowers to formal banks, making them reluctant to forward loans. On the demand side, the uptake of financial products and services is likely to increase with women’s empowerment and awareness, which remains low.

Adopting a gender-sensitive approach to the developing Indian financial markets can help bring more women to the mainstream. As a first step, maintaining a healthy network of female banking correspondents, complemented by suitable supporting infrastructure will encourage women’s mobility to banks. To further resolve issues of mobility, mobile financial services can be made increasingly available and accessible such that women can conduct transactions from their homes.

Another major concern is the slow adoption of digital financial services by Indian women. Secondary measures should be taken up that entails wider and deeper penetration by mobile and telecom businesses so that the inclusion of women can be optimised for them to avail better digital services.

To further resolve issues of mobility, mobile financial services can be made increasingly available and accessible such that women can conduct transactions from their homes.

Third, designing financial products targeted towards women will need a client-centred approach informed by studies on women and their interaction and relationship with money, financial products and technology, accounting for regional and socio-cultural variations as well. Designing elements like vernacular communication, voice and video enablers might reduce the friction that exists between women and technology.

Fourth, gender budgeting and targeting at an institutional level can enable in-design changes in public schemes that take care of specific needs and preferences of women and enhance their access to financial products. Such financial products should allow a greater degree of control and privacy related to income and spending decisions.

Fifth, digital literacy as well as banking awareness need to be more widespread. Banking awareness can help mobilise small savings and deliver these to last-mile women users. To advance this agenda, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has already launched a ‘Financial Education Initiative’.

Lastly, there is an urgent need for making available and using gender-disaggregated data to inform policy reforms and the creation of products and services, especially suited for women from low-income households. For example, the use of sex-disaggregated data can help financial service providers deploy mechanisms under the Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) focusing specifically on women, especially from marginalised segments. Hence, a periodic publication of such data on various parameters of financial inclusion can help policymakers track the gender gap in policy design and implementation, and the financial service providers to build women-centric products.

Gender budgeting and targeting at an institutional level can enable in-design changes in public schemes that take care of specific needs and preferences of women and enhance their access to financial products.

Reductions in financial inclusion gender gaps in India, through suitable reforms, innovations, and practices, can play a significant role in addressing economic inequalities, empowering women to play a more proactive role in advancing growth and development. Moreover, the inherent interlinkages in the SDG framework entail that improvements in SDG 5 are likely to prompt progress along other related goals on no poverty (SDG 1), food and nutritional security (SDG 2), good health (SDG 3), access to education (SDG 4), and, access to improved sanitation (SDG 6) and clean energy (SDG 7), besides directly impacting economic growth and levels of inequalities. Ensuring increased agency and meaningful participation for women can play a key role in the promotion of holistic progress along all the sustainable development goals, enabling a stronger and more resilient future for India.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Debosmita Sarkar is an Associate Fellow with the SDGs and Inclusive Growth programme at the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy at Observer Research Foundation, India. Her ...

Read More +