India is the world’s second-largest

producer, consumer, and importer of coal after China. In 2020, India had the fifth-largest coal reserves of over

111 billion tonnes (BT), just below China which had the fourth-largest reserves of

143 BT. Though coal reserves are comparable in quantity, China produced 3.9 BT of coal in 2020, five times more than India’s production of 759 million tonnes (MT). In November 2021 and again in April-May 2022, a crisis of power supply attributed to low coal stocks at thermal power generation plants led the Indian government to push generators to import coal. This advice came at a time when seaborne thermal coal prices were at their highest levels. An increase in the use of imported coal not only contradicts India’s strategy of self-reliance for energy security but also compromises the quest for affordability, an idea that underpins most of India’s energy policy choices.

Production and Imports

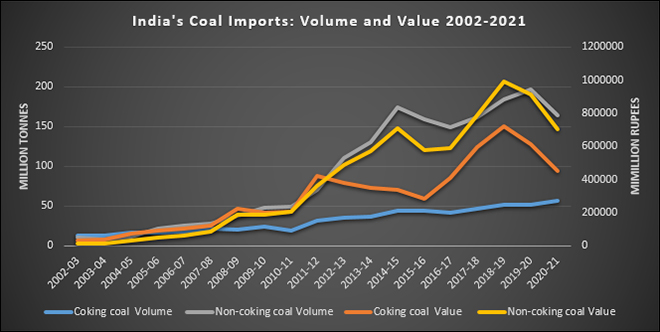

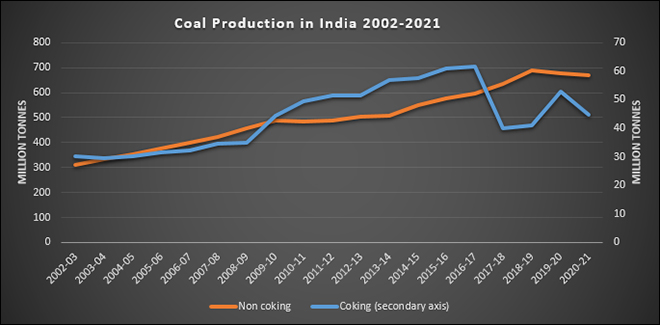

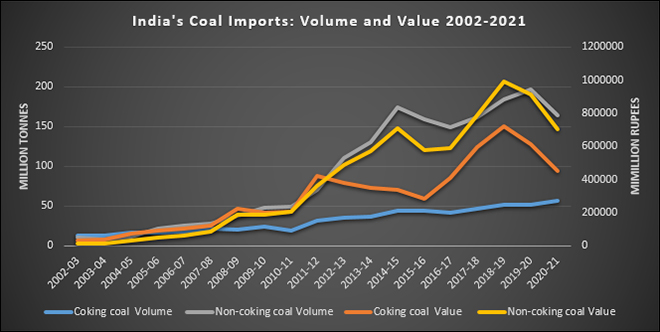

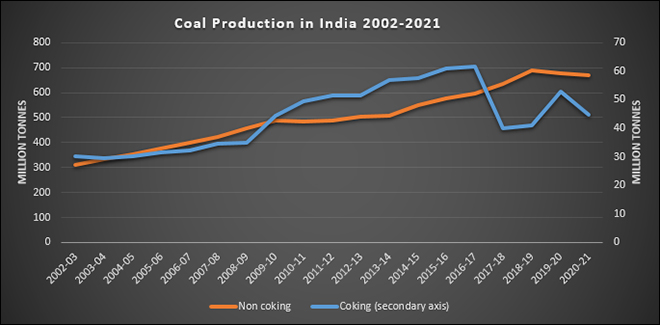

Raw coal (coking and non-coking) production in India increased from

341.272 MT in 2002-03 to

777.31 MT in 2021-22 implying an annual growth rate of just over 8 percent. Most of the growth came from an increase in production of thermal coal. Historically this has meant the

import of only coking coal as reserves were not adequate. However, as demand for power accelerated, coal was put under

open general licence (OGL) in 1993 that initiated thermal coal imports. Until the mid-2000s, volume of coking coal imports exceeded volume of thermal coal imports. This changed in

2005-06 when India imported

21.695 MT of thermal coal compared to

16.891 MT of coking coal. It was attributed to consumer (thermal power generators) preference for coal quality. Thermal coal imports accelerated with construction of imported coal-based coastal power plants. Between 2002-03 and 2019-20 (pre-pandemic year), coking coal imports increased from about

12.947 MT to 51.833 MT , whilst thermal coal imports grew from just

10.313 MT to over 196.704 MT in the same period.

An increase in the use of imported coal not only contradicts India’s strategy of self-reliance for energy security but also compromises the quest for affordability, an idea that underpins most of India’s energy policy choices.

Traded Coal Prices

Indonesia, Australia, and South Africa account for over

80 percent of India’s coal imports. In 2020-21, Indonesia accounted for

42.98 percent (92.535 MT) of India’s coal imports followed by Australia 25.53 percent, (54.953 MT), and South Africa (

14.45 percent, 31.093 MT). Indonesia was the largest source of thermal coal imports accounting for

55.56 percent, or 91.137 MT followed by South Africa (18.95 percent, 31.093 MT), and Australia (

10.98 percent, 18.008 MT). Australia alone accounted for

70.21 percent or 35.945 MT of India’s coking coal imports in 2020-21. When the price of coal increased in these markets,

imports fell by 13.7 percent (year-on-year, y-o-y) in August 2021, 9.1 percent in September and 3.4 per cent in October. Coal production grew by

8.6 percent from 716.08 MT to 777.31 MT but imports fell by 13.31 percent from

215.25 MT in 2020-21 to 186.58 MT in 2021-22.

Source: Coal Controllers Organisation, Ministry of Coal, Government of India

Source: Coal Controllers Organisation, Ministry of Coal, Government of India

Most of the reduction in imports was for non-coking (thermal coal) which fell from

164.05 MT in 2020-21 to

134.34 MT in 2021-22. This is typical of what happens in a ‘market’ when demand responds to price signals. One of the negative consequences of this market response was that electricity generation from power plants that rely more on

imported coal was adversely impacted. Some of these plants reverted to using domestic coal. This aggravated the domestic coal stock crisis. The federal government is attempting to counter the market response by

pushing thermal generators to import coal for power generation at a time when international coal prices are at their highest levels. This will impose costs on the Indian power system that is perennially teetering on the brink of financial distress. As of now it is not clear how this

additional cost burden will be shared (federal government, state government, thermal generators, distributers, consumers and other stakeholders).

China’s Coal Import Behaviour

In 2009, China, until then a net exporter of coal, imported

129 MT or 15 percent of globally traded coal. According to detailed analysis of the change in China’s coal trade behaviour, this did not imply a structural shift in global coal markets. There was no need for importing coal as China was producing

2.9 BT of coal a year that was adequate to cover demand. However, coal buyers in Southern China had entered the international market to minimise cost taking advantage of the price arbitrage spreads between domestic and internationally traded coal. China could easily

decide to buy 15-20 percent of globally traded coal when the price is right or just as easily stay out of the international market. The relationship between China’s domestic coal price and the international coal price is now one of the key factors in determining global coal trade flows. India on the other hand is forced into the international market for coal irrespective of prices because domestic production is unable to keep up with growth in demand. Weighted average international coal price (Indonesia, Australia, and South Africa) in rupees (quarterly exchange rate) has increased from around

INR4,000/tonne in 2020-21 to over INR

11,000/tonne in the first quarter of 2021-22. This is almost an order of magnitude higher than the average domestic coal price of

INR1,500/tonne through the same period. In contrast to China’s coal import behaviour that is described as one of ‘cost minimisation’, India’s import behaviour can only be described as one of ‘cost maximisation’, though not by design.

The federal government is attempting to counter the market response by pushing thermal generators to import coal for power generation at a time when international coal prices are at their highest levels.

Issues

Under the narrative of self-reliance (Aatmanirbhar) imported coal compromises India’s energy security. To address this challenge the government announced in 2020 that India will

become self-sufficient in thermal coal in 2023-24 with production from CIL (Coal India Limited) alone ramped up to 1 BT and logistical bottlenecks removed through coordination with the Ministry of Railways and the Ministry of Shipping. Ironically, imported coal is the fall-back fuel for power generation contributing to India’s energy security in 2021-22. Imported coal is also challenging the ‘affordability’ rationale that is used to justify the use of domestic coal over alternatives such as natural gas. In reality the frantic embrace of imported coal illustrates that what is unaffordable politically and economically is ‘no power’ rather than expensive power.

2011 was a year of energy supply disruptions and high prices due to

political upheavals in hydrocarbon producing regions that reduced hydrocarbon supply. Natural disasters

(tsunami) and its reverberations reduced world nuclear power and floods in Australia reduced

global coal availability. Annual average price of oil was highest ever above

US$100/barrel. Responses to these multiple supply disruptions were found immediately because countries such as Japan that were hit the hardest were well integrated with global energy markets. Coal and gas flowed into Japan making up for the loss of nuclear power that accounted for 30 percent of generation. The underlying message is that integration with international markets for fuels through prices and logistical networks is a better option for energy security, rather than nationalistic notions of self-reliance.

Source: Coal Controllers Organisation, Ministry of Coal, Government of India

Source: Coal Controllers Organisation, Ministry of Coal, Government of India

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

India is the world’s second-largest

India is the world’s second-largest

PREV

PREV