Agenda 2030 and the Asia-Pacific

The current “Decade of Action” has gained massive relevance in the journey towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), therefore, there needs to be a galvanisation of efforts to meet the 2030 deadline. While the COVID-19 pandemic has crippled economies worldwide, it has also directly and indirectly impacted a host of developmental parameters ranging from poverty and unemployment to gender equality and climate change, further widening the divergences in domestic socio-economic inequalities between advanced and developing societies.

The Asian Development Bank’s (ADB) 2021 report on key indicators for Asia and the Pacific region underlines the pandemic-induced impediments to the region’s ability to attain several SDGs. The recently published 2022 report on key indicators by the ADB shows that while some nations in the region are poised to bounce back, issues such as potential stagflation, cross-border conflicts, and threats to food security may prevent substantial economic progress from returning anytime soon. This edition of ADB’s annual exercise highlights the role of social mobility in countries, as crucial to achieving the SDGs by the end of this decade.

For impactful transitions to occur, several upward drivers need to be improved upon which can positively impact an individual’s health, education, income, employment, and location, all of which are key factors.

Social Mobility Index

Social mobility refers to the transition of people, including families and other social units, between the socio-economic strata within their lifetime. The movement of some people in and out of poverty varies across developing nations in Asia. For impactful transitions to occur, several upward drivers need to be improved upon which can positively impact an individual’s health, education, income, employment, and location, all of which are key factors. During the pandemic, these drivers were severely impaired, thus, denting people’s ability to experience positive social mobility in their lifetimes. Upward social mobility holds the essence of sustainable development because it endorses comprehensive growth and promotes social convergence in terms of access to resources, within and across nations. If developmental trajectories are not holistic and inclusive, they fail to be sustainable.

The World Economic Forum’s (WEF) created a Social Mobility Index in 2020 which ranks 82 nations and identifies areas for promoting shared opportunities in the economy. The index evaluates 10 pillars as apt indicators of a nation’s social mobility including health, access to education services, social protection, fair wage rates, and inclusive learning, amongst others. The report estimated that higher-income nations in Europe and North America tend to fare much better in terms of social mobility, thus, raising concerns for poorer countries from Latin America and the Caribbean, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa which constitute the lower end of the index rankings.

Table 1: Global Social Mobility Index 2020

Source: World Economic Forum

Source: World Economic Forum

Social Mobility vis-à-vis sustainable development

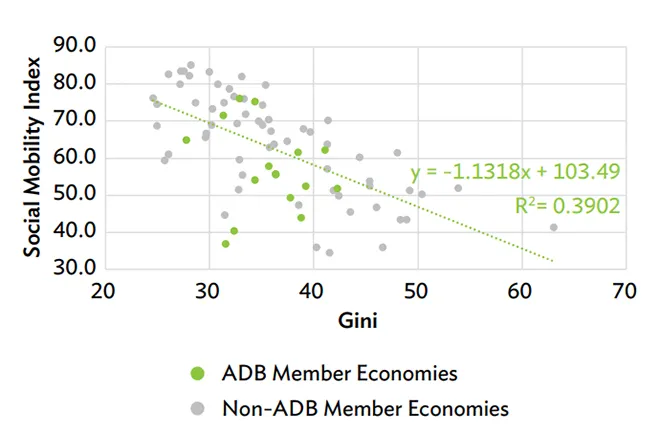

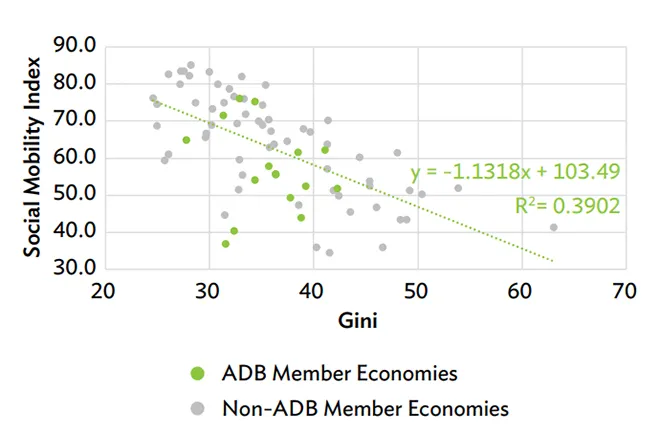

There exists a direct linear relationship between a country’s income inequality and its social mobility scores. On one hand, nations with greater social mobility enhance access to equally shared opportunities, while on the other, higher income inequalities impede social mobility. The downward slope in the figure below is an indicator of a negative relationship between the Gini Coefficient (a statistical indicator of economic inequality in a country) and their inherent social mobility. This meant that economically unequal societies had far lower scores for social mobility indicators from 2015 to 2019.

Figure 1: Correlation Between Social Mobility Index and the Gini Coefficient

Source: Asian Development Bank Estimates

Source: Asian Development Bank Estimates

Nations that have a higher degree of social mobility can have better success at reducing extreme poverty domestically. Firstly, the identification of sectors with high levels of poverty prevalence but low social mobility would require strong policy intervention due to the inability of persons to elevate their socio-economic status with the resources available to them. In such situations, it is essential to ensure that interventions are inclusive, thus, imbibing the basic tenets of sustainable development within itself. Secondly, upward social mobility of the lowest section does wonders for society as a whole in terms of improving resilience to exogenous shocks such as the pandemic. Given, that the distribution of economic prospects in ADB member economies had shrunk by about 69 percent post the pandemic, if resource equity can be established at various levels, it will invariably trickle down to further generations in the long run, with more sustainable progress.

Social mobility and the pandemic

Predicting how the pandemic would have affected societies had they had better social mobility is difficult to accurately determine, given the lack of data. However, projections certainly indicate that the nations where such mobility was low before the pandemic will end up experiencing longer periods of socio-economic setbacks. Despite this, developing nations in Asia are expected to bring down the occurrence of extreme and moderate poverty to 1 and 7 percent respectively by 2030. However, such outcomes will only come true if the risks associated at the intersection of economic growth and social mobility are wisely addressed. Prior to the pandemic, less than half the population in 72 percent of the ADB member nations were covered by social protection benefits. Though several newer cash and benefit schemes were brought in as a response to the pandemic, it is essential for such recovery measures to extend beyond a few years. Policy responses must be targeted to uplift those who were at the lowest socio-economic rungs before 2020 and help them achieve greater degrees of social mobility.

The identification of sectors with high levels of poverty prevalence but low social mobility would require strong policy intervention due to the inability of persons to elevate their socio-economic status with the resources available to them.

As mid-2022 highlights the halfway mark towards Agenda 2030, it is now also crucial to identify parameters on which high-quality, accurate and timely data must be gathered to direct resource requirements for social mobility and corresponding policy action. This will be extremely crucial for the Asia-Pacific, given the highest concentration of the world’s population and a large number of emerging markets in the region, which will chart the direction of the global economic order more significantly in the years to come. Action on the developmental parameters will not only have a strong bearing on making the domestic economies and communities more resilient but also decide the dynamics of foreign investments and congenial business climate in the region.

(The author acknowledges Rohan Ross at NLSIU, Bengaluru, for his research assistance on this essay.)

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV