-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

< style="color: #333333;">Now that the dust has settled on India's failed bid for membership in the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) at the Seoul meeting in June — no small thanks to China — Beijing's stance is being interpreted as a sign of its 'contain India' strategy at worst, and anti-India balancing (by hyphenating India's case for NSG membership with that of Pakistan's) at best. Failure to join the NSG has been widely interpreted as a failure of Modi's high-profile diplomacy. Modi the pragmatist has signalled unilateral concessions to China in the past such as opening the possibility of visa-on-arrival for its nationals. His foreign office will now be forced to open new diplomatic fronts in face of growing Chinese obstructionism. The contours of this counter-offensive against China could be driven by three signals — presented here in increasing order of sharpness — and change the optics of the India-China relationship, from the current passive-power play to that of a leading power unafraid to seize diplomatic initiative.

After the NSG meeting in Seoul, a section of Indian commentators called on the government to pull India out of plurilateral groupings such as BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation — where China too is a prominent member. That would be a self-goal as far as India is concerned, since it would be a tactic admission that these groupings are China-led (which they are not). The game for New Delhi, instead, would be seize the diplomatic initiative in these groupings and block Chinese desiderata in concert with other members, much in the same way the UNSC P5 is often split by one or more powers acting in concert. Second, India should be aggressively propositional in these groupings. Take BRICS for example. India's presidency of that grouping this year presents an excellent opportunity for it to present a view of BRICS as a liberal, constructive, institution focussed less on politics (an arena where there is little convergence between the five member states anyway) and more on economic development. As a corollary, any Chinese attempt to turn BRICS into an anti-western political forum — say, one that takes a China-friendly position on the South China Sea dispute — should be sharply resisted. Finally, India should adopt a primus-inter-pares position when it comes to BRICS by pushing through its own pet projects like the New Development Bank Institute (which PM Modi proposed last year).

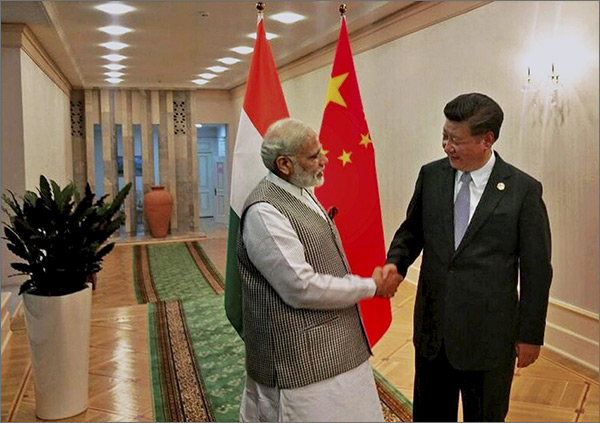

PM Narendra Modi with Chinese President Xi Jinping before SCO meeting in Tashkent, 2016 | File Photo

PM Narendra Modi with Chinese President Xi Jinping before SCO meeting in Tashkent, 2016 | File PhotoThe second signal would be to release an Indian national security strategy publicly, along the lines of what the United States does. This official document would have the imprimatur of the Cabinet Committee on Security (CCS), and would present an analysis of Indian national-security challenges. In particular, it would delineate the threats China poses, as well as policy options to meet those threats. Publication of such a document would reflect India's growing perception of China as a hegemonic power. As has been known through the many US initiatives along these lines — most recently through the Pentagon's annual public report on Chinese military capabilities — public articulation of perception of governments in themselves often signals diplomatic and military resolve. Such signalling-through-articulation strategy has precedence in India. For example, in 2003, the CCS released a very short note on India's nuclear doctrine which served to communicate India's nuclear red lines, thereby strengthening its deterrence posture.

Taiwan and Tibet remains China's key pressure points. The final signal India could send to out is willingness to further engage with the leaderships of Taiwan and Tibet. India has maintained a thinly-veiled conceit when it comes to Taiwan. While ascribing to the 'one-China' theory Beijing advocates, it has engaged with Taiwan through trade promotion and social engagements. New Delhi could retaliate against Beijing by dropping this guise a shade further, and prominently host Taiwan's new nationalist president Tsai Ing-wen whose election has had Beijing unnerved. This could be through one of the new Track 1.5 engagements of the Ministry of External Affairs, like the Raisina, or Gateway of India dialogues. It could also be in the form of concessional terms of trade for Taiwanese firms interested in doing business with India. It could also make the Dalai Lama and his more hard-line cohorts more visible in New Delhi's policy circuit. Again, this could be achieved in partnership with sympathetic think-tanks and media houses, or in the name of Buddhist diplomacy, an innovation of the current dispensation which could be leveraged much further.

These diplomatic signals would also have to be complimented with military diplomacy with southeast Asian states, and through defence sales to countries historically antagonistic to China — like that of the Brahmos missiles to Vietnam. Together, these actions will most certainly affect the few areas where the two countries have indeed exhibited convergence of policy, like climate change negotiations. However, the cost of not retaliating against China's aggressive containment diplomacy is signalling pusillanimity. In diplomacy, under-reaction (like over-reaction) is a cardinal sin.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Shachi Adyanthaya Portfolio Manager Childrens Investment Fund Foundation

Read More +