-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

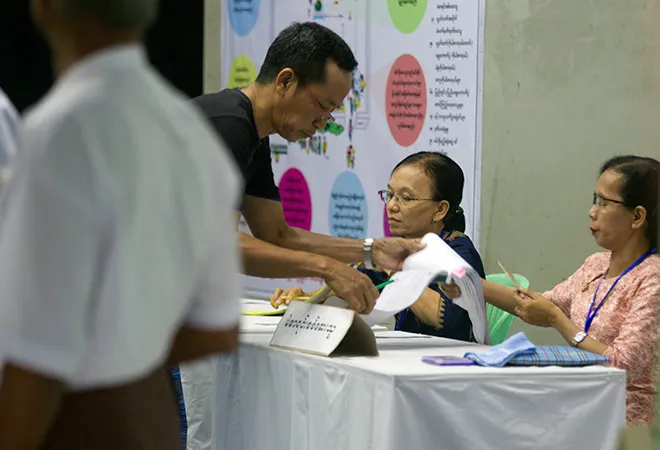

On 8 November, Myanmar will hold its third general elections since the political reforms were initiated in 2010. Many see the upcoming elections as an important test of the country’s transition away from direct military rule. The struggle for democracy against authoritarian rule remains a key factor in Myanmar’s politics, though it does not tell the entire story. Recently a commentator rightly observed: “for most of the people of Myanmar, this upcoming election is very important, not just as an opportunity to choose a person or political party to run the government, but as a way to continue their unfinished struggle to rid the country once and for all of military control.”

This is a popular narrative among citizens of Myanmar, particularly the majority Burman ethnic community. It also partly explains why the ruling National League for Democracy’s (NLD) leader and Myanmar’s State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi remains popular at home, even as her international image has been marred over the country’s treatment of its minority Rohingya Muslims and an important factor why the party may to return to power. For many voters, the upcoming elections provide another opportunity “to cement the country’s fledgling democracy and to see more positive changes, politically and economically.” The democratisation discourse looks slightly different from the perspective of ethnic minority communities for whom the political reforms story has been a mixed bag.

The reforms period saw resurgence of violent conflicts in many ethnic areas including between the Kachin Independence Army and the Myanmar military after a 17-year-old ceasefire agreement broke down in 2011 and emergence of new conflicts such as between the Arakan Army and the Myanmar troops in recent years that have intensified in the past few months. Several tens of thousands of civilians have been forced in internally displaced persons (IDPs) camps. Against this backdrop, ethnic candidates and parties standing for the upcoming elections have focused on issues around building peace, safeguarding ethnic rights, and establishing federalism. The inability of the NLD regime to find resolutions to some of these issues is in part the reason why it faces challenges in ethnic states in the November elections.

For some ethnic minority communities, the upcoming elections mean very little as they may ultimately stay out of the process itself. Myanmar military has already suggested delaying elections in five townships in the ethnic areas including in the Wa Self-Ministered Division and northern Rakhine State for security reasons. The country’s election commission will decide on whether to delay voting in these townships in early October.

The reforms period also saw the Rohingya Muslim community were stripped of their citizenships and had faced military atrocities that pushed hundreds and thousands into neighbouring Bangladesh as refugees and another 100,000 confined in IDP camps, many of whom are denied the right to vote. For many Rohingyas, there is very low expectations from the November elections. Aye Win, one of the six Rohingyas who have been approved to stand in the election, has no hope of winning unless Rohingyas are granted citizenship so that they could vote.

Some compare the upcoming elections with the 2015 elections. For Kyaw Hla Aung, a Rohingya community elder, there were some people whose names appeared on the voter list in 2015 “but this time, there is no voter list.” This has further smashed faith in the upcoming elections. There is a sense of despondency among this ethnic minority community. As Kyaw Soe Aung, a leader of one of three Rohingya parties observed: “We can understand the previous situation, that previous governments backed up by the military did not follow the democratic norms. But it is difficult to understand that Aung San Suu Kyi and her democratic government would do the same.” Rights groups have raised concerns and questions about the integrity of Myanmar’s November election and has called on the UN Human Rights Council’s special rapporteur to Myanmar to “safeguard the integrity” of the elections.

Despite the disappointments towards the transition process, the willingness and enthusiasm of ethnic minority parties to participate in the November elections suggest their faith in the democratic process. However, the significance of the elections may not necessarily be the same as it is framed by the pro-democracy parties including the ruling NLD party. The NLD seems to be positioning itself to be an inclusive party by increasing number of local ethnic candidates in ethnic areas and including two Muslim candidates in its list of candidates for the November elections.

The ruling party also seems to face a dilemma: Aligning itself strongly with the majority Burman community increases its ability to consolidate its position vis-à-vis the military-backed parties and thus strengthen the democratisation story, but that narrative limits the party’s ability to push forward the ethnic agenda, which affects its own position in ethnic areas.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

K. Yhome was Senior Fellow with ORFs Neighbourhood Regional Studies Initiative. His research interests include Indias regional diplomacy regional and sub-regionalism in South and Southeast ...

Read More +