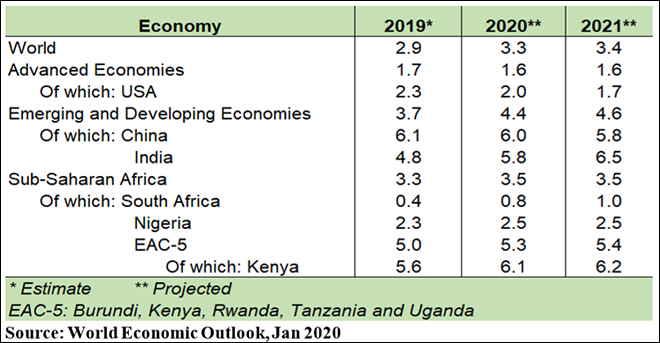

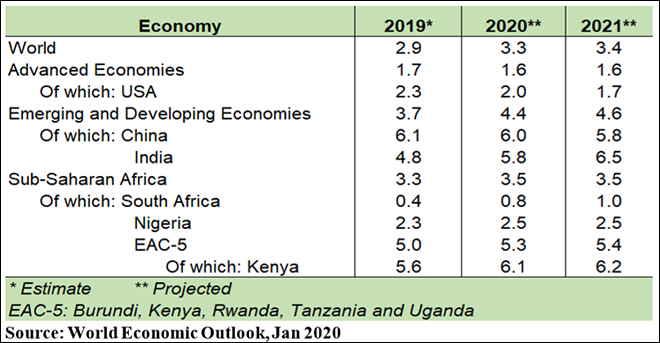

There is no greater demonstration of the risks of economic forecasting than the quick revisions that have followed post the declaration of Covid-19 as a global pandemic. The International Monetary Fund’s revision of global economic growth from a January figure of 3.3%, were subsequently revised to -3% during the release of the World Economic Outlook in April 2020. In the space of three months, global forecasts from institutions with longstanding experience swung by a massive 6.3 percentage points. Caught in this tumultuous change of global fortunes are several African countries including those of the eastern Africa region.

Forecasts anticipated a respectable growth level for the world, with countries of sub-Saharan Africa expected to grow at 3.5% in 2020. Within the Sub-Saharan Africa region, the expected growth for the five countries of the East African Community (EAC-5)<1> was 5.3%. These figures seemed sensible at the time owing to the fact that some countries in Sub-Saharan Africa had locked in annual growth rates that exceeded global averages in the last five years. In addition, four of the EAC-5 were disproportionately represented among the top 15 globally. The exception among EAC countries was Burundi, whose political challenges caused economic stagnation. Despite the growth for EAC-5 being from a low base, they had been on a good run in the last decade, and the major concern was to convert this growth run into a structural change by converting labour from subsistence agriculture to light manufacturing.

Table 1: Comparison of projected Economic Growth Rates (2019-2021)

While Kenya’s growth prospects remained impressive, selected EAC-5 countries were showing pressures related to high debt servicing costs relative to public revenues, high fiscal deficits, weakening currency and the risk of sharply reduced harvests on account of the expected second phase of the desert locust infestation. Kenya has been contending with reduction in contribution of private investment to GDP growth despite high growth rates, suggesting that private firms were in an extremely weak position. These threats were well within the sightlines of managers of public affairs but the risks changed dramatically on 13 March, 2020 when a diagnostic test confirmed the first person infected with the novel corona virus in Kenya’s territory.

Based on the April edition of the World Economic Outlook 2020, the growth forecast for the east African region has seen a resounding revision. Having accounted for the shock of the COVID-19 pandemic, the growth prospects of the entire Sub-Saharan Africa region have been revised to -1.6% for 2020 but with the expectation of a quick recovery to reach 4.1% growth in 2021.It may appear that the effects of the crisis on the African continent, despite being sudden and deep are not long lasting, but this forecast highlights the fact that the trajectory of growth will at best, be one percentage point lower than the baseline before the emergency. For Kenya as well, this is a large and irrecoverable loss.

Economic Manifestation of the Crisis

Kenya is a regional hub for international travel, with Kenya Airways being the leading airline on the continent travelling to more than 40 international destinations. Thus, International tourism and Air Travel were the first to feel the impact Covid-19 has had on global and national economies. Kenya like most countries in the world suspended international air-travel, and due to the complementary nature of these sectors freezing of international travel led to end mass cancelations of hotel bookings. The direct effect of these cancellations was a reduction in employment opportunities and reduced incomes for remaining employees.

Kenya’s tourism sector is not only a major employer but also linked to others sectors such as energy, agriculture and manufacturing. Suppliers of services and goods used within the tourism industry experienced low demand for services such as travel and food. The reduction in tourism had a spatial unemployment effect because major tourism sites are at the coast of Kenya and a few other areas. Many hotels in these areas wound down operations for an indefinite period, creating second order adverse effects on other industries.

The Kenyan Government had understood that in order to combat the spread of Covid-19 it was imperative to slow the pace of infection. However, it was faced with the complex situation of heeding the advice of epidemiologist- which was a full scale “Stay at Home” policy, while safeguarding the economic interests of thousands of daily wage workers. To institute a full-scale lockdown that a large share of a shocked population supported carried direct risks of unemployment and no wages with the certainty of mass suffering in urban areas. The need for a reduction in social interactions carried another risk of protest by poorer populations living in densely populated neighborhoods rendered unemployed by the shutdown.

The daily reports of results of the diagnostic tests showed that a majority of the infected had a recent history of international travel but their interactions with other Kenyans prior to quarantine suggested that there were underlying infections that had not been discovered due to limited diagnostic testing. However, the numbers demonstrated that Nairobi and Mombasa, the largest urban concentrations and home to about 10% of Kenya’s population, were the hot spots being the locus of international airports and places with the highest share of international visitors. The government reasonably responded with a dawn to dusk curfew and later augmented it with the limitation of entry and exit from identified hotspots with exception granted only to providers of essential services.

Policy Choices

It is not evident whether the government of Kenya acknowledges that the economic crisis caused COVID19 is not a normal policy challenge amenable to a solution in the form of conventional economic stimuli. However, this realization is crucial as it has to be the starting point of any effective long-term policy planning for the revival of the economy. For instance, the Central Bank of Kenya’s earliest policy response was understandably a reduction of interest rates and the reserve ratio requirements for banks to enable onward lending. This is only mildly helpful because the need to shut down a large part of the economy to prevent community spread disproportionately affects urban based small firms who would be unable to borrow.

Renowned economist, Dr. David Ndii, in an open letter to the Kenyan president urged him to promptly create a lifeline fund to support firms that will be unable to keep functioning during the inevitable reduction and suspension of activities. In his letter Dr. Ndii has voiced concerns that the governments responses are predicated on policy choices that would be ineffective given that character of this crisis comes from supply side shocks. Additionally, he estimates that a lifeline fund of about US$ 1-1.5 billion would prevent the decimation of firms and alleviate serious suffering. The government of Kenya seems to have ignored this proposal despite its modest cost- relative to the size of Kenya’s GDP, the multiplier that it would generate and the fact that it does not impose an undue fiscal burden on the government

The IMF and the World Bank called for OECD governments to grant low-income countries a chance to suspend debt servicing for six months to help them tide over these troubled times. OECD member states have acceded to this request, though – it is not clear if Kenya qualifies as 30% of its public debt in 2019 was held by private banks and the possibility of suspending payments to them is very low.

Conclusion

There is no doubt that the pandemic will have adverse effects on the economies of the EAC-5 with the global slowdown it has caused affecting demand and for commodities and exports for all these countries. The lesson of the moment is that this pandemic has accidentally exposed the fragility of the EAC countries based on their debt servicing obligations and limited state capacity to absorb shocks and the structure of their economies. At present, it appears that the mitigating factors are the demographic advantage of these countries owing to large youthful populations, which are comparatively less vulnerable to acute illness from the virus. When the crisis passes, an enduring issue for reform will be to ensure structural transformations.

<1> The East African Community (EAC)_5 are Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, Burundi and Rwanda. They have been joined by South Sudan in 2016 bringing the number of member states up to six. (https://www.eac.int/eac-history)

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV