-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

An effective COVID-19 vaccine could help us emerge from isolation and end the social distancing measures that have come into play during the pandemic. But it will only work if people are willing to be vaccinated.

The Foundation for a Smoke-Free World conducted a survey in June of 2020 that addressed whether people’s willingness to use a COVID-19 vaccine and adopt other preventive healthcare measures was associated with trust. The survey was conducted in nine countries—China, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, South Africa, Sweden, the UK, and the US. A thousand individuals were surveyed in each country, and the responses were weighted to the most recent census data.

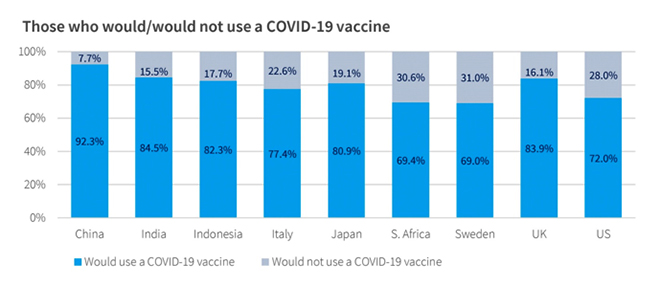

While an average of 86 percent of respondents had increased the number of times they washed their hands in April and May 2020, an average of 21 percent said that they would not get vaccinated. These figures were highest in Sweden (31 percent) and South Africa (30.6 percent), but were not much better in the US (28 percent) and Italy (23 percent) (See Figure 1). Unfortunately, many of these levels barely reach the cusp of vaccine coverage needed to achieve population-wide herd immunity against COVID-19.

Figure 1

Sources show that the public is most concerned with vaccine effectiveness and the risk of side effects. Worry about side effects has historically had a big influence on vaccine acceptance. In the UK, concern about reported neurological complications from common childhood vaccines lowered the vaccination rate from 81 percent in 1974 to 31 percent in 1980, leading to a resurgence of pertussis that resulted in over 100,000 cases. In 2018, 20 percent of respondents to the Wellcome Global Monitor survey in the UK said they believed that the risk of vaccine side effects was fairly high or very high.

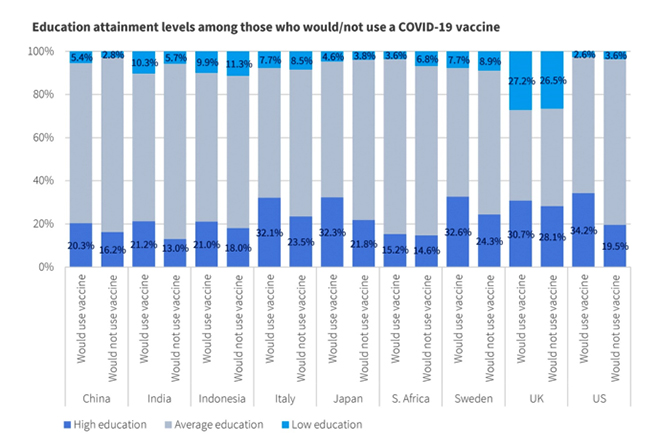

Interestingly, our survey showed that respondents who said they would get vaccinated were more highly educated than those who said they would not get vaccinated. These results were highest in the US and Sweden (See Figure 2). This may mean that people with higher education levels have more information, but this correlation will need to be further explored before it can be explained.

Figure 2

Legend. Education levels were condensed into three categories: high, average, and low. Those who did not complete high school were placed in the ‘low education’ group, those who completed high school or those with some university education were placed in the ‘average education’ group, and those who had graduated from university or had pursued even higher levels of education were placed in the ‘high education’ group. Those who said they would use a COVID-19 vaccine had higher proportions of individuals in the ‘high education’ group than those who indicated that they would not use a vaccine.

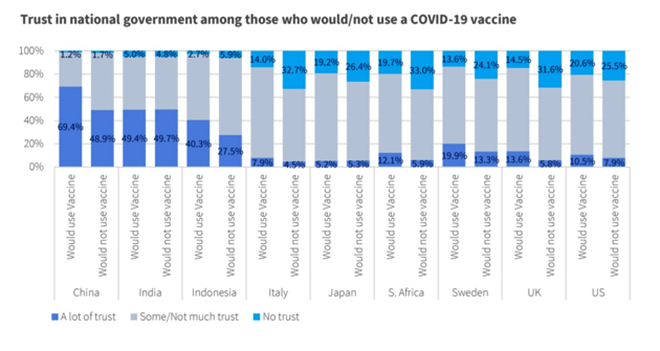

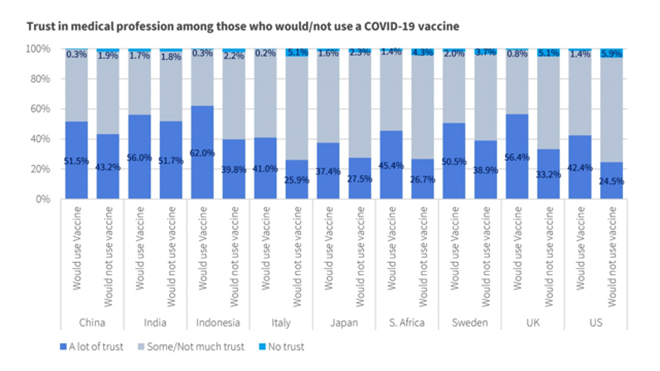

Dr. Bruce Gellin, US Deputy Assistant Secretary for Health and the Director of the National Vaccine Program in the Department of Health and Human Services, has said that the foundation that underpins vaccination acceptance is trust. Our survey explored respondents’ trust of both their national government and the medical profession (See Figures 3 and 4). Except for China, India and Indonesia, most respondents had relatively low levels of trust in their national government, but most of the respondents said they trusted the medical profession. Trust in both entities, but especially in the medical profession, was generally higher among those who said they would get vaccinated. These findings emphasise the importance of having medical professionals lead messaging about vaccine safety, effectiveness and benefits.

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 4

Legend. Levels of trust in the national government and the medical profession were

Legend. Levels of trust in the national government and the medical profession were

condensed into three categories: ‘a lot of trust’, ‘some or not much trust’, and ‘no trust’.

In general, there was a strong sense of trust in the medical profession. Those who said

they would use the vaccine displayed higher levels of trust than those who said that

they would not use the vaccine.

A recent piece in the Journal of the American Medical Association on flu vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic stated that strong, unified messaging is essential for vaccine compliance. The article cites the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s call to action that urges physicians to make every effort to get their patients vaccinated and acknowledges that physicians and healthcare professionals are the most trusted source for accurate information on vaccine risks. The role of medical professions in preventing larger public health crises that could overwhelm the world’s healthcare resources cannot be overestimated.

We suggest that healthcare professionals partner with their national governments and international healthcare experts, such as the World Health Organization, to create consistent, accurate messages about the benefits of vaccination for COVID-19. These messages should use simple language that people with no more than an elementary education can understand; acknowledge peoples’ fears about vaccine side effects and cite accurate, verifiable data on side effect risks; and state whatever data is available on vaccine effectiveness. This will ensure that a greater number of people will get vaccinated as soon as a vaccine is ready, leading to the potential end to the current COVID-19 pandemic.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Dr. Derek Yach is the president of the Philip Morris International-funded Foundation for a Smoke-Free World.

Read More +