This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

Peak Coal

The

slow growth in demand for coal from India, China and the rest of the World during the three pandemic years strengthened the narrative of

peak coal. Lower than expected growth in electricity demand combined with aggressive competition from policy-supported renewable energy (RE), particularly solar power that gets priority access to the grid (‘must run status’) resulted in significant

overcapacity in the coal and power value chain in India.

100 GW (gigawatt) of approved coal-based power generating projects were in the pipeline in 2020 in India but most projections concluded that these will

not be built as RE was expected to meet growth in demand for electricity. Annual investment in the Indian power sector

halved in 2019 compared to its peak in 2010. The global outlook for coal was far more discouraging.

In 2020, the International Energy Agency (IEA), categorically stated that global coal demand

peaked in 2014 and coal use in power generation is likely to peak before 2030. Coal use in China, which accounted for 50 percent of global coal consumption, was expected to

peak around 2025. Global coal demand was not expected to return to its pre-COVID-19 levels and coal’s share in the global energy mix was expected to fall

below 20 percent for the first time since the industrial revolution. In 2020, global coal demand fell by about

7 percent because of the lockdown across the World and the consequent decrease in demand for electricity that consumed roughly

65 percent of global coal production. Policies designed to phase out coal, supportive policies for RE along with cheap natural gas also contributed to coal’s decline in Western economies.

Global coal demand was not expected to return to its pre-COVID-19 levels and coal’s share in the global energy mix was expected to fall below 20 percent for the first time since the industrial revolution.

Though coal demand in India was projected to increase in the foreseeable future accounting for

14 percent of global demand by 2030, growth in coal demand was projected to be substantially lower than what was expected earlier. The IEA expected demand for coal (for power generation) in India to increase only by

2.6 percent annually till 2030. Some reports suggested that demand for coal for power generation in India

peaked in 2018 and is unlikely to return to pre-COVID-19 levels given the high target set for RE by the government. Post COVID trends in coal demand growth in India suggests that this view reflected hope rather than reality.

Coal Demand Growth

In 2014, the year that was supposed to represent

“peak-coal” according to the IEA, global coal demand was 5.680 billion tonnes (BT) in which thermal coal used for power generation accounted for

4.347 BT or over 76 percent. In 2021, global coal demand was

7.947 BT in which thermal coal demand was

5.350 BT. Coal demand growth stubbornly refused to oblige projections of peak coal in 2014. In 2021 coal demand was close to its all-time high contributing to the

largest-ever annual increase in global energy-related carbon dioxide (CO

2) emissions in absolute terms. According to the IEA, coal demand in China, increased by

4.6 percent or 185 MT (million tonnes) in 2021 despite the extended lockdowns reaching an all-time high of

4.230 MT. India’s coal consumption crossed the

1 BT mark in 2021 with a consumption of

1.053 BT of, a new all-time high and the largest amount consumed in a single year by any country other than China. Indian coal consumption increased by

12 percent or 117 MT in 2021 compared to 2020. Going by data from the government of India coal demand crossed the 1 BT mark in 2021-22 recording a consumption of

1.027 BT. In 2022-23, coal demand had crossed 1.078 BT by January 2023.

Domestic Coal Production

In 2014, the Government of India set a target of increasing coal output to

1.5 BT by 2019-2020 with 1 BT coming from Coal India Limited (CIL) and its subsidiaries. In 2019, the target date for increasing coal production to

1.5 BT was revised to 2023-24. In December 2020, the Ministry of Coal (MOC) reiterated the goal of

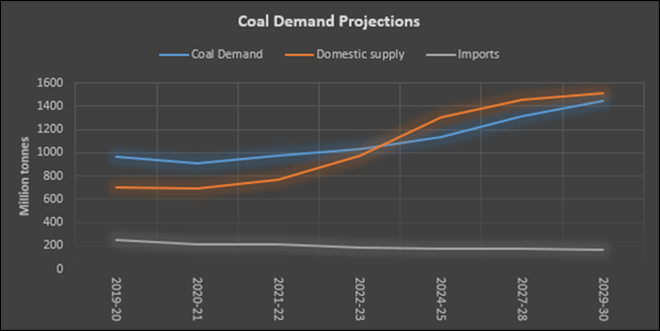

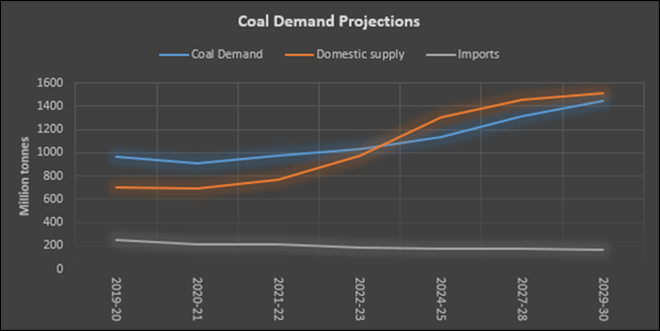

1 BT coal production by CIL in 2023-24. According to the MOC, coal demand was expected to grow from 955.26 million tonnes (MT) in 2019-20 to

1.27 BT in 2023-24 and domestic production was expected to increase to make India self-sufficient. In 2022-23 coal demand was

1.029 BT.

To achieve the goal of 1.5 BT, domestic production of coal must grow at close to about

7 percent annually. This is not an impossible target. Between 2008-2010, domestic coal production grew at an annual average rate of about

7 percent. In the decade 2001-02 to 2009-10, coal production grew at over

5 percent on average. However, in the decade 2010-11 to 2019-20, production growth fell to an average of about

3 percent. This is despite the fact that investment in coal supply

nearly doubled in 2010‐19. The slowdown in the economy was among the key reasons. In 2019-20, the production of raw coal in India was

729.1 MT with a minuscule growth of 0.05 per cent over the previous year. In the period April-October 2020, coal production declined by

3.3 percent year on year to 337.52 MT. Import of coal grew at a much faster rate. In 2019-20, total import of coal grew by

5.6 percent to 248.54 MT compared to 235.35 MT in 2018-19. Import of non-coking coal grew at

7.2 percent to 196.704 MT in 2019-20 compared to 183.510 MT in 2018-19. Between 2019-20 and 2022-23 coal demand increased at an annual average of

2.5 percent and it is expected to increase by an annual average of 5.8 percent in 2022-23 to 2029-30 to

1.448 BT. Coal supply including imports is anticipated to increase faster at an annual average of 7.8 percent in 2022-23 to 2029-30 to

1.511 BT.

The government is optimistic that an increase in domestic production of coal will bring faster economic development to the ‘aspiring regions’ of the country.

CIL’s report “

Roadmap for Enhancement of Coal Production” seeks technical and administrative interventions at the supply end to increase coal production. The report

lists investment in railway lines, mechanisation of mining, large-scale contract mining along with quick land acquisition, faster environmental clearance and state-level approvals as the means to achieve the goal of increasing domestic production.

The government has a broader perspective. According to a government-appointed high level committee headed by the vice-chairman of

NITI Aayog that had the mandate to liberalise the coal sector, coal is not to be viewed as a source of revenue but instead, be considered as an input to economic growth through the sectors consuming coal. Under this new paradigm, the committee recommended that the government should focus on early and

maximum production of coal and work towards its abundant availability in the market. The government is optimistic that an increase in domestic production of coal will bring faster economic development to the ‘aspiring regions’ of the country. The

MOC has stated that increasing domestic coal production will not only reduce imports and save precious foreign exchange but also create jobs in economically challenged coal-rich states. With investment in resource (coal) rich states, the government believes that economic development will follow. To attract investment, the government has opened coal resources for

commercial mining and it expects that commercial production of coal will have a positive impact on the production and processing of steel, aluminium, fertilisers and cement.

The government is also expanding the market for domestic coal through exports and through diversification into non-coal businesses. The government has extended the right to exploit

coal bed methane (CBM) from India’s large coal seams to the private sector. In addition, it is promoting surface

coal gasification (a cleaner option compared to burning of coal) to produce synthetic gas (syngas) that could be used to produce

energy fuels such as methanol & ethanol, urea (fertiliser) and also chemicals such as acetic acid, methyl acetate, acetic anhydride, di-methyl ether, ethylene, propylene, oxo chemicals and poly olefins. The government has set a target of

100 MT coal gasification projects by 2030. Two gasification projects, one on high ash coal blended with pet coke (

Talcher Fertiliser plant) and the other from low ash coal (

Dankuni Methanol Plant) have been established on pilot basis.

The government is also expanding the market for domestic coal through exports and through diversification into non-coal businesses.

Peak coal: Stubborn target

Global coal use is set to surpass

8 BT for the first time in 2022 eclipsing the previous record set in 2013, according to the IEA. Globally higher

natural gas prices amid the global energy crisis have led to increased reliance on coal for generating power. In China, the world’s largest coal consumer,

a heat wave and drought pushed up coal power generation during the summer, even as strict COVID-19 restrictions slowed down demand. In India

heat waves in 2021 and 2022 increased the demand for coal-based power for cooling and irrigation. The demand for coal-based power in India and elsewhere is likely to continue in 2023 as record heat waves are anticipated on account of

El-Niño. The push to move peak coal closer and the push back from heat waves that have moved peak coal further away are both driven, rather ironically, by climate change.

Source: Ministry of Coal, Government of India

Source: Ministry of Coal, Government of India

Lydia Powell has been with the ORF Centre for Resources Management for over eight years working on policy issues in Energy and Climate Change.

Akhilesh Sati has over fifteen years of experience as a programme manager for ORF's energy initiative.

Vinod Kumar is a Assistant Manager, Energy and Climate Change Content Development of the Energy News Monitor Energy and Climate Change

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This article is part of the series

This article is part of the series

PREV

PREV