The last few days have been quite momentous in the history of the Indian space policy landscape. The appointment of Pawan Kumar Goenka, the former Managing Director of Mahindra & Mahindra as the Chairperson of Indian National Space Promotion and Authorisation Centre (IN-SPACe) indicates that the announcement of the new space-related policies favouring space entrepreneurship aren’t just promises on paper but represent a tangible shift in the vision of the government for the space programme. The further announcements to de-regulate the telecommunication sector has reinvigorated the identity of India as a market for satellite and telecommunication applications. However, these developments notwithstanding, a few concerns remain viz., the lack of single window clearances due to the overlapping/concurrent jurisdiction of the Department of Telecommunication and Department of Space for satellite communication applications; the conspicuous failure of the government’s new policy outlook being translated into a legislation; the draft spacecom policies and remote sensing policies stopping short of providing the clarity and predictability that is considered conducive for investments; and the precise functions, responsibilities, and powers of IN-SPACe, the new industry regulator, not being defined within the framework of a law.

These shortcomings whether for the space sector or in other sectors, have played an undeniable role in India’s turbulent history with Bilateral Investment Treaties (BIT) and international trade and investment obligations, which is well-documented through arbitral awards and decisions rendered in the Antrix-Devas dispute, the Cairn Energy PLC & Anr. v. Republic of India, and Vodafone International Holdings BV v. Government of India arbitrations, and the dispute between the United States (US) and India with regards to the local content sourcing policies of India in the solar industry. The traditional schools of thought within the administration saw the partnerships with the private industry in areas like defence and space as rendering national interests vulnerable by virtue of their placement thereof in the hands of persons not entirely controlled by the state. However, that school of thought is beginning to change as is evident from the developments in the space sector.

Nevertheless, a policy shift first requires a policy objective to be defined. Thus, it is useful for us to ask ourselves, what is it that we aspire for in space? The beginning of India’s space odyssey was rooted in a normative approach, which advocated a strict compliance with international space law. Accordingly, its space programme was state driven, rooted in a philosophy that space technology should largely facilitate welfare objectives on Earth. The creative distinctions between weaponisation and militarisation, which might have held some allure for the Indian defence forces, did not assume a significant role in ISRO’s space programme. Whether or not India’s space programme even recognised that the precise nature and scope of the non-appropriation principles of the Outer Space Treaty was up for debate, is unknown.

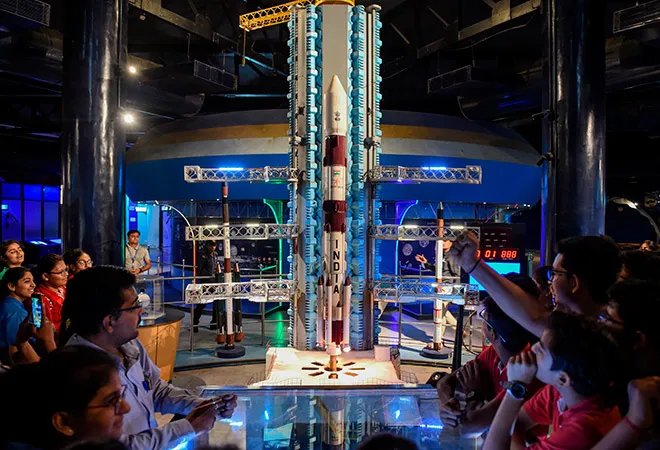

The beginning of India’s space odyssey was rooted in a normative approach, which advocated a strict compliance with international space law. Accordingly, its space programme was state driven, rooted in a philosophy that space technology should largely facilitate welfare objectives on Earth

Thus, India may not have anticipated the predicaments that were to arise, when certain states declared space as a separate domain in their military doctrines and legitimised the exploration of space for mining precious resources. The Indian defence forces, scientists, and engineers have done well to enable us to catch up with these realities. However, our idealistic interpretation of international space law certainly deprived us of the vision to be ahead of these trends and instead left us reacting to them. In addition, a space programme divested of real world international political perspectives, left the nation vulnerable to dependance and reliance on foreign nations and vendors for critical space-based defence and communication needs, such as satellite imagery and defence/maritime communication, a fact highlighted by General VP Malik in his book, “Kargil From Surprise to Victory”, on the Kargil War.

Simultaneously, not having a robust and vibrant satellite communication and remote sensing industry left ISRO to singularly shoulder India’s ambitions in the orbital domain around Earth. While ISRO’s achievements in space is undisputed, especially given the constraints of sanctions under which it operated, the fact remains that India’s ability to negotiate for orbital slots and frequencies in the International Telecommunication Union becomes challenging if there isn’t a thriving domestic industry with a large appetite for such orbital resources. One wonders, if we have, therefore, capitalised on our proximity to the Equator, the availability of abundant skilled workforce, a huge market, and stable rule-of-law-based democratic structure enough to make India a premiere geography, not just for consuming satellite applications but to become an exporter of the same.

Even as India now makes the move to assert its legitimate economic and defence interests in the orbit around the Earth, other nations like US are actively scouting for means to leverage deep space through plans for colonisation of the Moon and mining of asteroids. The potential disruptive effects of such activities on terrestrial economics are, as yet, unclear. But nevertheless, we could be a witness to the beginning of the new “Gold Rush”. In this changing landscape, if India becomes reliant on foreign vendors and nations to support its own efforts to capitalise on the gold rush, the strain on the Indian fiscal deficit mitigation programme and the pressures on our independence in international diplomacy and politics, would not be unlike those imposed by our historic reliance on defence equipment from foreign vendors. The only way to resist the allure of taking sides in the emerging space race best exemplified by the Artemis Accords led by the US and the International Scientific Lunar Station (ISLS) led by Russia and China, would be an indigenous industry capable of giving the nation a leverage to assert our history of non-alignment even in our ambitions for space.

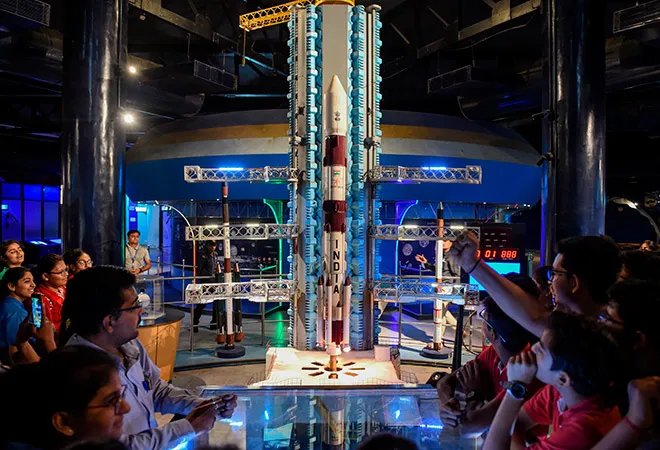

The need for a transformation of the Indian space policy landscape goes beyond just the need for creating jobs or for improving tax revenues from the market for space activities

To conclude, the need for a transformation of the Indian space policy landscape goes beyond just the need for creating jobs or for improving tax revenues from the market for space activities. On the contrary, a robust private sector in critical areas like space and defence strengthens our independence in the international arena, provides us means to forge international alliances, assert our interests in evolving international space policies, and reduces our need to align ourselves with the ambitions and policies of other nations when it comes to the domain of space. At the very least, it improves our track record for complying with international trade and investment obligations and assures our space bureaucrats that their decisions, when taken on the basis of the policies guiding them, renders them immune to judicial review from the domestic courts and liability under BIT litigations. More importantly, a policy consistent with international trade and investment obligations provides our entrepreneurs and scientists, who are amongst the best and the brightest in the world, with a sense of national support and validation; thus, ensuring to their benefit, a policy enabled ease of access to capital and corresponding absence of legal risks. It may very well be the shot in the arm the nation needs for its indigenisation goals and its ambitions to become a powerful player in global space politics.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV