-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The Putin-Modi summit as part of the Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok was a step further in Indo-Russian relations.

The Putin-Modi summit, the participation by India’s PM as chief guest in the Eastern Economic Forum (EEF) at Vladivostok, and the agreements signed in meetings, were a step further in Indo-Russian relations on standard lines of projection of goodwill. There was a significant twist, though, which if pursued, may place the two governments on a collaborative path to economically steer beyond defence purchases or trade in oil and natural gas.

At Vladivostok, in a move going beyond cooperation on bilateral terms or within the limits set by BRICS and SCO, Russia was placed firmly within India’s Act East policy framework. India, in turn, was located within the boundaries of Russia’s attempts to utilise sub-regional arrangements for development purposes in her Far East, and became linked to Mr. Putin’s Greater Eurasia policy perspectives. Official statements have said as much. Delegations and speakers at the EEF indicate that steps will be taken to further these goals. As a bonus India may gain access to Global Russia’s resources in east and Southeast Asia, resources that have grown in the last few years with Russia’s pivot to Asia.

India’s acquisition of the S400 defence system is in the offing, but comparable purchase has drawn US sanctions on China. It is questionable, even if India gets a waiver in this case, as to how far other acquisitions will go ignored.

The developments open a new dimension to Indo-Russian economic relations at a time when standard parameters of the relationship are being challenged, owing to US sanctions regimes. The latter is based on provisions of CAATSA (Countering America’s Adversaries through Sanctions Act) that target institutions dealing with Russia in critical areas, the litmus test being dollar transactions scrutinised by the Treasury. The implications pose a threat to the pivot of India’s post-Soviet relations with Russia — the interdependence centred on defence procurements, where Russian supplies of air force and naval equipment have recently led the way. The purchases exist within a framework of technological transfer, involving public sector units and private manufacturers as well, as innovative cooperative production in the Brahmos project that has the potential to generate international value chains. India’s acquisition of the S400 defence system is in the offing, but comparable purchase has drawn US sanctions on China. It is questionable, even if India gets a waiver in this case, as to how far other acquisitions will go ignored.

True, much has linked India and Russia economically beyond this core relationship, but what is involved has yielded only limited prospects. Atomic energy production cooperation at Kudankulam has the potential for evolution in the same direction as defence production, but India has only taken up a fraction of the offers made by Russia. The Russian state has played a part in assisting India’s programme to diversify its energy range through investments abroad, clearing the way for India’s role in Sakhalin oil and purchase of Imperial Energy. However, such assistance has been capped, with investment in Vankor and Sakhalin-3 fields awaiting confirmation to enhance the trend.

Indian investments in Russia have been limited, though immensely successful for short periods.

Otherwise, commerce in goods and services has been modest, hovering around the $10 billion mark at best. Links have been established between Indian manufacturers and traders with post Soviet private enterprises linked in “financial Industrial groups” and “holdings” often joined by “oligarchic” arrangements and state corporations or government initiatives, but easy capital flow between the two banking systems is difficult. Relatively modest Indian trading enterprises, dealing in a variety of goods, have been of importance in maintaining momentum in exports of textiles and other manufactures and commodities to Russia. Here however, the scale falls short of exports to the US or EU in conditions where Russia’s imports from China and Turkey are substantial. Successful product-specific trade of a high order — and significant to both countries — has been systematically undertaken only by Indian pharmaceutical majors. Indian diamond imports from Russia have also witnessed growth, but in both areas the relationship has been restricted to standard commercial operations that lack long term staying power. Indian investments in Russia have been limited, though immensely successful for short periods, as some have been more tentative unlike others. Russian investments in India have been sizeable but few, and often brokered by the state.

The bottom line is that the private sector has failed to establish the material foundations for the long standing bilateral diplomatic and strategic relationship advanced by BRICS and SCO: a relationship intended to take up the slack left by uncertainties in US-India common ground. Foundations elsewhere may disintegrate owing to sanctions.

To create a space for such mutual collaboration in the Russian Far East, firm steps have been taken at the EEF.

To include a domain of collaboration for sub-regional/regional development in the relationship, with governments acting as godmothers, is an unusual gambit, by way of riposte. The move may be of global significance if it is followed by steps towards direct rupee-rouble exchange as discussed in public circles in late July. As it stands, the current project envisages development of the bilateral relationship through focused action within a scenario of multilateral networks in east and Southeast Asia. This could involve the Eurasian Economic Union through its free trade partner, Vietnam, as well as through Russia itself.

To create a space for such mutual collaboration in the Russian Far East, firm steps have been taken at the EEF. To establish a full reconnaissance of the region’s potential and form basic networks, the Indian delegation included official representatives of ministries and agencies that handled transport (to handle connectivity), finance, coal and oil and natural gas (to explore synergies in these areas). Their presence was strengthened by Indian entrepreneurs with a fair interest in the region and a good knowledge of the post-Soviet Russian economy. Indians took up threads with Korean, Chinese and Japanese officials and entrepreneurs with a long experience of the region.

Clearly, though, Indian companies, have a poor acquaintance with Russia’s unusual business environment, unless in sync with local interests or the Putin government. Awareness in India of the region might be promoted by the Centre for Regional Trade in Delhi, the Indian School of Business and the Amity University consortium who were represented at Vladivostok. But Amity’s brief is mainly to act as a fillip to awareness of India in the region, to spur the demand there for Indian services and professionals, rather than to strengthen Indian awareness of the Russian Far East.

In the short term, the scope of Indian enterprise collaboration will have to be sustained by intergovernmental arrangements — as in the case of diamond mining/oil/gas concessions.

In the short term, the scope of Indian enterprise collaboration will have to be sustained by intergovernmental arrangements — as in the case of diamond mining/oil/gas concessions. State to state collaboration involving state corporations such as defence goods monopoly, Rosoboroneksport, or energy actors Gazprom or GAIL may work out value chains that are of mutual benefit, touching east and Southeast Asia. This could centre on the heavy demand in Southeast Asia for Russian military equipment and energy products.

Assistance in these operations may come from Global Russia, i.e. the presence of the Russian state outside the country and including tight control over Russian businessmen and interest groups holding resources abroad. Here, the list of Russian “oligarchs" fixed in the East is small compared with those with offshore wealth in the West; but the list includes tycoons Oleg Deripaska (aluminium) and Alexei Repik (pharmaceticals) and others who work with Hong Kong and Singapore stock exchanges or east Asian partners.

Whatever the case, in current circumstances, in contrast with other aspects of India’s Act East policy, the government will determine what is to become of the new turn in Indo-Russian relations. It is the state that has promoted this initiative on both sides, almost wholly unallied to private interests. And it is the state that will decide the future of the initiative, even if major private players find a place in what will happen.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

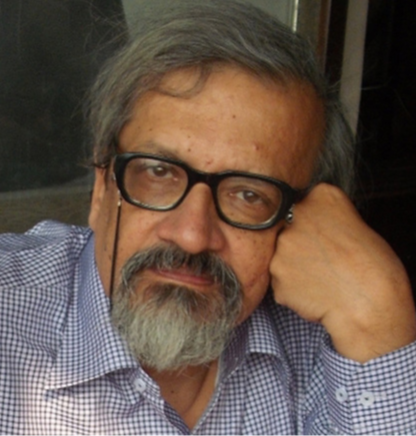

Prof. Hari Vasudevan(15 February 1952 10 May 2020) was a renowned historian who studied Russian and European history and Indo-Russian relations. He was a Visiting ...

Read More +