-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Image Source: iStock/Getty Images

The state of the World’s Children report has been a major UNICEF publication since the 1980’s that presents an overarching analysis of the global trends impacting children. The 2019 report focuses on the “changing face of malnutrition”, and portrays the triple burden of malnutrition, in forms of undernutrition, hidden hunger and overweight, as an ongoing battle that multiple nations are facing simultaneously that seriously threatens the growth and development of their children and economies.

Nutrition and health are inherently linked to the development of a nation's human resources. Their relationships are reciprocal and cyclical. Healthier citizens exhibit higher working capacities, in turn leading to more economic output, increased incomes, reduced poverty and better lifestyles.

However, in today’s fast paced world centered around globalization and rapid urbanization, communities are substituting their previously healthier diets for a modern processed one. These unhealthy eating habits have resulted in an increase in lack-of-nutrition induced non-communicable diseases that have become a major threat to public health in general. Extreme climate shocks too, are a major contributor to this diet substitution, as it has caused displacement of people, forcing them to abandon their farms, and follow the trail of ultra-processed supermarket food in urban locations.

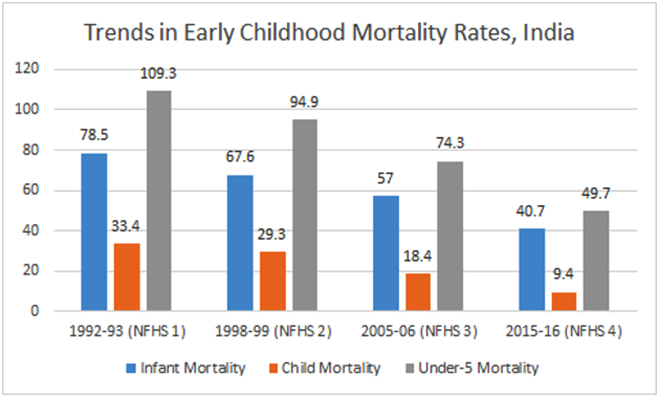

According to the report, under the age of five, one in three children are undernourished or overweight, and one in two children suffer from hidden hunger, visible in terms of stunting (type of undernutrition when children are too short for their age) and wasting (extreme type of undernutrition when children are too thin for their height). There are high instances of mortality associated with malnutrition, and of perinatal mortality (number of stillbirths and deaths in first week per 1000 total births) that are globally reflected in the report. India alone reports infant mortality at 40 per 1000 live births, and under 5 child mortality at 49 (Graph 1).

The report raises the question of why many children are consuming such little of what they need, coupled with many children largely consuming what they don’t. The answer lies in nutrition transition, and food environment and its marketing.

The impact of gender has been widely explored in the said report, as it identifies the role of women as primary caregivers, and discusses the challenges women face participating in the tertiary or three tier service sector, while also being solely responsible for most child feeding and care. It establishes a direct correlation between malnutritioned women rearing a malnutritioned child and emphasizes the need to economically empower women to include them in the process of decision making to ensure the right to proper food, nutrition and health of the households.

Although the global reasons for increased malnutrition may be the shift from consuming seasonal traditional foods to an increased consumption of processed foods, the reasons for India to be battling this burden are quite different. India as a country has been facing grave levels of hunger, for reasons such as worsening climatic conditions, unsafe water, and open defecation. Large number of people existing without any sanitation facilities, and unhealthy feeding and care practices, are also contributing factors which compromise with children’s capacities to absorb nutrients, and threatens public health.

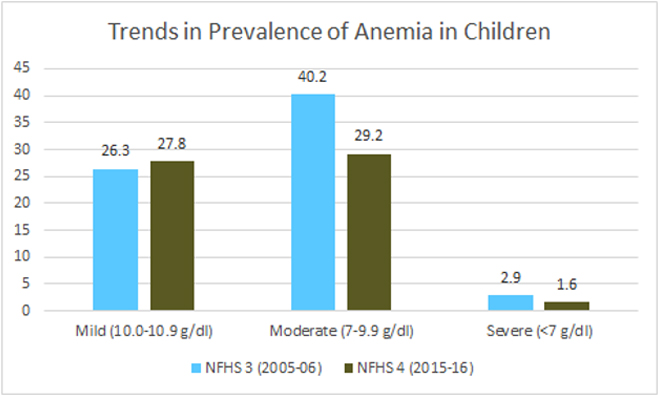

The latest SoWC states that in India, 35% of the children are suffering from stunting, 17% suffer from wasting, 33% are underweight and 2% are overweight. The diagnosis of hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes, mostly adult diseases, were also found in high intensity among the Indian children. 40.5% children were found to be anemic and so was every second woman. India also witnessed the highest deaths because of malnutrition, as many as 69%, among children under the age of five, per year, with over eight lakh deaths reported in 2018.

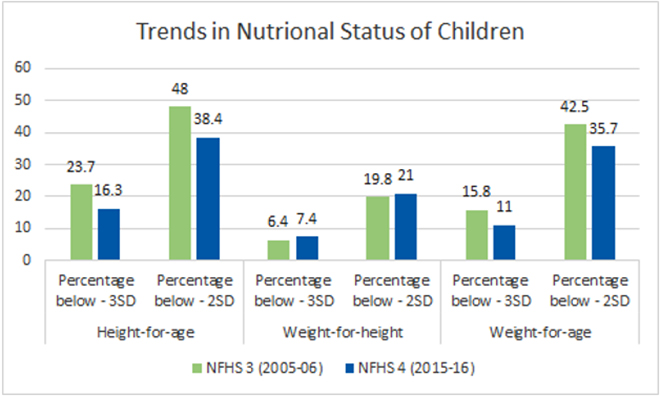

Although the numbers concerning mortality, anemia and other nutritional indicators put India quite low on the global index, the internal trends have rather improved since the last few years. The National Family and Health Survey of India, has been documenting the trends concerning the mortality, morbidity, immunization, nutritional status and maternal health status since 1992 onwards and it shows progressive growth across all parameters, as seen in the graphs below. Graph -1 documents the significant drop in infant, child and under five mortality in India across the last four NFHS reports. Among children between the ages of 6 to 59 months, 58% are anemic; however, it is a serious improvement since the last estimate was 70%. The variations of anemia prevalent is children is reflected in Graph 2.

The results of the most recent Comprehensive National Nutrition Survey (2016-18), portray a more positive story for India, furthers the findings of NFHS 4. It shows a decline in stunting from 38.4% to 34.7%, decline in wasting from 21% to 17.3%, and a decline in underweight children from 35.7% to 33.4%.

GRAPH 1

Source: NFHS

Source: NFHS

GRAPH 2

Source: NFHS

Source: NFHS

The Global Hunger Index 2019, too ranks India at 102’nd out of 117 countries, based on the four indicators of undernourishment, child mortality, child stunting and child wasting. However, it is argued that it is hard to calculate the improvements made by India across the four parameters in the last five years, and compare with the previous GHI scores and rankings, as additional data and countries are added in the ranking every year. Moreover, the rankings are awarded based on the average value of a three year period, 2016-18 for undernourishment; 2014-18 for wasting and stunting and of 2017 for under-five mortality, making the estimations quite dated.

GRAPH 3

Source: NFHS

Source: NFHS

Multiple government plans and policies are behind this progressive growth against malnutrition, such as the Mid-Day Meal Programme, the National Iodine Deficiency Disorders Control Programme, Special Nutrition Programme, Integrated Child Development Services, National Plan of Action on Nutrition, the National Nutrition Mission, establishment of Nutritional Rehabilitation Centres and Village Health Sanitation & Nutrition Committee and many others. There has also been the implementation of numerous indirect policies in order to provide nutrition to all, such as the expansion into the public distribution system, improved purchasing power of the poor households, reducing the vulnerability of the poor through the provision of health and immunization facilities, and ensuring food security through increased grain production and community participation.

The Indian government’s efforts in strengthening the health infrastructure, and combating health & nutrition problems as a priority have been well reflected in the wide set of programmes and schemes to tackle malnutrition, that have been globally accredited. POSHAN Abhiyaan (National Nutrition Mission), has played a major role in improving nutrition indicators across India. It focuses on the first 1000 days of a child’s life, and operates through a convergence across ministries. The idea behind the scheme is to ensure initial and exclusive breastfeeding and helping the mothers induce complementary feeding into the child’s diet. Currently, only 55% of the children are exclusively breastfed and 10% are introduced to complementary foods other than milk. The 6X6X6X strategy of six target beneficiary groups, six interventions and six institutional mechanisms, has also been highlighted in the SOWC report, for the use of anemia testing as a way of providing healthy diet information.

Moreover, initiatives inclusive of Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojna (PMMVY), which offers conditional cash transfer for pregnant and lactating women, have benefitted over 98 lakh women so far.

The report ultimately concludes that lack of proper nutritious food among children impairs their physical and cognitive growth. These children will also be at a higher risk for low immunity, increasing infections, poor learning skills, and in many cases, death.

It needs to be seen what more steps India can take towards a malnutrition free future.

There is necessity to pursue higher alignment amongst ministries and all the existing nutrition programmes to extradite better nutritional levels from the conception of pregnancy till adolescence. The National Nutrition Strategy is a well set aim, but needs to be implemented till the last grass root level for visible improvements. The plan aims to make India malnutrition free by 2022, by reducing stunting levels in children, and anemia in children and women. Furthermore, higher involvement of women in the decision making process regarding the overall nutritional needs of the children and themselves is key. It is possible to gain better nutritional outcomes for women and children through a deeper integration of technology and community mobilization, and by paying greater attention to the urban trends of the food consumption market.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.