-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

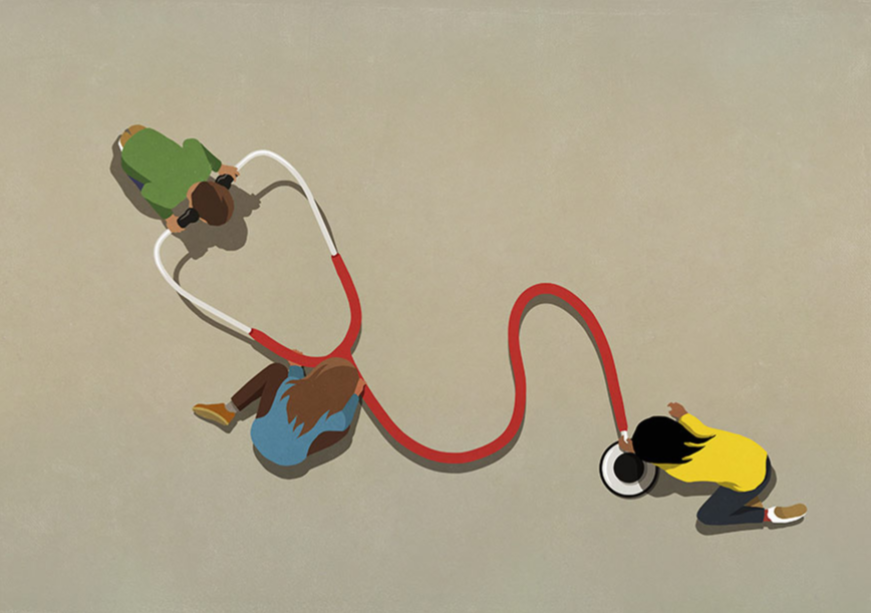

Adopting holistic approaches to address the interlinkages between health and other gender-sensitive SDG targets is key to achieving equitable and sustainable health outcomes for all

This essay is part of the series titled: World Health Day 2024: My Health, My Right

The world celebrates 7th April as World Health Day every year to commemorate the foundation of the World Health Organization (WHO). The theme marking this year’s celebrations is ‘My health, my rights’, which aims to advocate for accessible and quality healthcare services, education and information for all individuals, regardless of geographic, social or cultural locations. Today, the ‘Right to Health’, which includes the right to manage and control one’s health, bodily integrity, and informed consent; active decision-making in health-related matters, and protection from torture, ill-treatment, or harmful practices, is constitutionally mandated in at least 140 countries worldwide. Health as an inherent human right has been acknowledged in various international documents, including the WHO Constitution (1948), the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), and several global and regional human rights treaties.

A “threat multiplier”, climate change significantly endangers women’s health rights, particularly in the most vulnerable communities of the Global South.

Despite these oft-reiterated commitments, more than 4.5 billion people worldwide still lack access to essential health services and protection. Among the various challenges that confront a ‘fit-for-purpose’ global health architecture, there is an urgent need to redesign health systems resilient to the impending climate crisis and its associated health risks, with gender considerations becoming a critical aspect. A “threat multiplier”, climate change significantly endangers women’s health rights, particularly in the most vulnerable communities of the Global South. Recognising the need to mainstream the climate-health-gender nexus in global dialogue, COP28, in partnership with WHO, organised the first-ever Health Day and climate-health ministerial. This article focuses on delineating the gender dimensions of this climate change-induced health crisis, a pressing issue that must be highlighted and accounted for in designing climate-resilient health systems.

Climate change poses significant risks to human health through various channels. The environmental ramifications, from rising sea levels to altered precipitation patterns and intensified weather events, directly and indirectly affect human well-being. Direct effects involve exposure to extreme temperatures, like heat waves or cold spells, exacerbating pre-existing health conditions such as respiratory diseases. Additionally, extreme weather events such as hurricanes can cause injuries and disrupt public services, further impacting health. Indirectly, climate anomalies heighten the risk of infectious diseases such as malaria, dengue, meningitis, and cholera. While the linkages between climate and health have been historically acknowledged, they have received limited attention in research, development, and policy-making. However, with the intensification of climate impacts witnessed among the most vulnerable populations, interest in addressing the health challenges posed by climate change has reignited, necessitating renewed dialogue and coordinated efforts from the climate, health, and development sectors.

Direct effects involve exposure to extreme temperatures, like heat waves or cold spells, exacerbating pre-existing health conditions such as respiratory diseases.

Mitigating the public health impacts of climate change is complex, as both environmental factors and individual decision-making shape health outcomes. For instance, anticipated increases in regional heat waves, a consequence of climate change, could pose widespread health risks. However, proactive measures such as identifying vulnerable groups like women, children, and the elderly and ensuring access to preventive measures could mitigate their adverse health effects. Numerous other factors contribute to this vulnerability, including biological susceptibility, socioeconomic status, and cultural context.

Specific initiatives, including the 2008 World Health Day “Protecting Health from Climate Change” campaign, exemplify global endeavours to integrate climate resilience into healthcare strategies. A report titled “Protecting Health from Climate Change: Global Research Priorities” emphasised key themes, highlighting the imperative of embedding the health impacts of climate change within broader efforts to enhance global health equity. In this context, it is imperative to stress the importance of assessing the costs and benefits of specific mitigation and adaptation strategies and enhancing policy-relevant risk assessments to better link gradual change in health risks with climate variability.

In its 2023 Review of Health in Climate Policy, the WHO has necessitated prioritising and integrating public health into national efforts to combat climate change. While the adverse health implications of climate change have been blatantly evident in recent years, there has also been substantial progress in incorporating health considerations into nationally determined contributions (NDCs) and long-term low emissions and development strategies (LT-LEDS). Currently, 91 percent of available NDCs integrate health aspects, reflecting a significant increase from 70 percent in 2019. Moreover, there is a growing trend towards developing climate targets and policies that promote health across various sectors, including mitigation, adaptation, means of implementation, Loss and Damage, and long-term sustainable development strategies.

While the adverse health implications of climate change have been blatantly evident in recent years, there has also been substantial progress in incorporating health considerations into nationally determined contributions (NDCs) and long-term low emissions and development strategies (LT-LEDS).

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) acknowledges that women encounter elevated risks and bear a heavier load of the consequences of climate change. This is particularly evident in terms of health effects, amplifying gender-related health inequalities and disparities. In over 141 countries worldwide, more women, on average, than men die during natural disasters, particularly in countries where a larger share of women live in or are vulnerable to poverty. The severity of disasters further amplifies these differences, underscoring the gendered impact of climate-related events.

In urban areas of developed countries, mortality rates have been observed to rise with higher deviations from the optimal temperature. Warmer temperatures may decrease winter deaths but increase mortality during summer, with women exhibiting significantly higher levels of vulnerability. Rising temperatures also contribute to the spread of malaria, disproportionately affecting pregnant women who face increased risks of complications such as spontaneous abortion, premature delivery, stillbirth, and low birth weight. During windstorms and tropical cyclones as well, women are disproportionately affected due to relative immobility, as evidenced by the 1991 cyclone disaster in Bangladesh, where 90 percent of victims were women. Similarly, in drought-prone regions of many developing countries, women bear the excess burden of water scarcity, confronting the health hazards of fetching water from contaminated sources, leading to waterborne diseases like diarrhoea—a significant cause of child mortality.

Furthermore, developing a nuanced understanding of the gender-based health disparities between the Global North and the Global South is crucial to mainstreaming women’s evolving role in climate-health policy. In the Global South, women are often viewed as passive victims of environmental degradation, with health issues arising from factors such as toxicity, natural disasters, or socio-economic changes linked to agricultural modernisation and land use alterations. Conversely, women in the Global North are viewed as more environmentally conscious and actively involved in promoting their well-being. However, lived experiences often defy these simplified narratives. Consequently, there is an urgent need for frameworks that acknowledge these complexities at play.

Rising temperatures also contribute to the spread of malaria, disproportionately affecting pregnant women who face increased risks of complications such as spontaneous abortion, premature delivery, stillbirth, and low birth weight.

Amidst climate change-induced challenges, it is increasingly evident that the intersection of climate, health, and gender is paramount in understanding and addressing global health disparities. Recognising health as a fundamental human right, it is vital to integrate gender-sensitive perspectives into climate and health policies to mitigate adverse impacts, especially in vulnerable regions of the Global South. Efforts towards gender equality and social justice are integral to building resilience and promoting health justice and well-being in the face of climate change. Embracing intersectionality and adopting holistic approaches that address the interlinkages between health and other gender-sensitive SDG targets can be crucial to achieving equitable and sustainable health outcomes for all. Incorporating a gender-sensitive approach within current climate, development, and disaster risk reduction policy frameworks can potentially mitigate these impacts. Thus, collaborating across multiple economic sectors, enhancing data collection and monitoring, tracking gender-specific objectives, and ensuring inclusive participation of all key stakeholders is imperative. Empowering women as catalysts for the societal transformation of climate policy can enhance the effectiveness of formulating gender-responsive mitigation and adaptation policies.

Debosmita Sarkar is a Junior Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation

Rhea Sharma is a Research Intern at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Debosmita Sarkar is an Associate Fellow with the SDGs and Inclusive Growth programme at the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy at Observer Research Foundation, India. Her ...

Read More +