With all the nerve-racking anticipation doused on 2 May, Mamata Banerjee’s Trinamool Congress (TMC) swept the West Bengal legislative assembly elections in 2021. The Bengal elections were crucial for India’s political ecosystem for several reasons. Firstly, it was a tough battleground with the ruling TMC facing competition from the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Congress-Left Front-Indian Secular Front (ISF) alliance. Since BJP’s phenomenal rise in the country from 2014, this was the first Vidhan Sabha election in Bengal where the BJP had presented itself as a dominant force. Incidentally, West Bengal is also one of the few states where the BJP has not yet ruled either directly or through its allies. Secondly, as the main contest was between TMC and BJP—the flurry of election issues that gained momentum in the last few years, such as the Citizenship Amendment Act, political violence, management of Cyclone Amphan, religious identity and caste politics, and the raging pandemic—made any kind of political speculation extremely difficult.

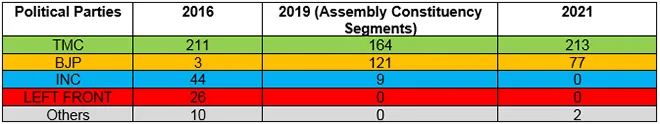

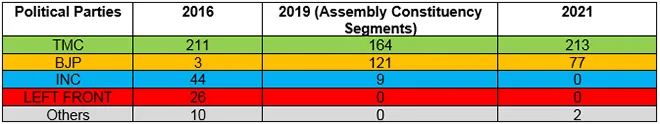

A recent report by the Observer Research Foundation prior to the Bengal elections, analysed the key political themes and cross-party swings in the assembly segments from the 2016 Vidhan Sabha elections to the 2019 Lok Sabha elections in the state of West Bengal. Out of the total 294 assembly segments, 118 swung to BJP (from various other parties including the TMC) and 38 swung to TMC (from other parties but BJP) between 2016 to 2019. One seat swung to Indian National Congress (INC) from TMC in the Samserganj assembly constituency of Murshidabad district. Of the remaining 137 seats where no cross-party swings were observed, TMC carried 126 of its seats, BJP retained three of its previous seats and INC, eight of its previous seats from 2016 to 2019. However, the 2021 results were clearly bipolar—with TMC winning 213 seats and BJP strengthening its hold in the opposition lobby from 3 seats in 2016 to 77 seats in 2021. The Congress-Left-ISF alliance won one seat with a Rashtriya Secular Majlis Party (of ISF) ticket in Bhangar assembly constituency.

Table 1: Legislative Assembly Seat Share in West Bengal (2016, 2019 & 2021)

Source: Election Commission of India

Source: Election Commission of India

(Note: In all the three elections in 2016, 2019, and 2021, the Left Front and INC had formed a political alliance; since 2019 saw Lok Sabha elections, the party-wise leads in the assembly segments are considered for analysis here; in 2021, election results were concluded in 292 (not 294) assembly constituencies due to death of candidates in the remaining two before the polls.)

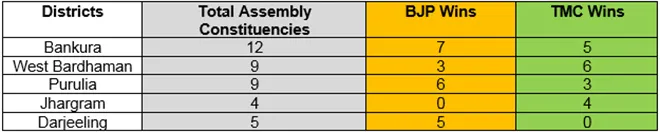

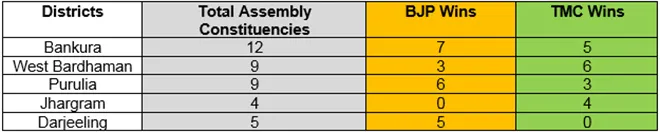

The districts in Jangal Mahal, mainly Bankura, Purulia, West Midnapore, and Jhargram, have contributed heavily in strengthening the TMC tide in 2021. Interestingly, the districts of Bankura, West Bardhaman and Darjeeling saw a complete swing to BJP from various other parties between 2016 to 2019—where BJP was leading in all the assembly segments. Purulia and Jhargram were able to retain only one TMC segment, while the rest of the assembly segments in these two districts had the BJP leading in 2019. However, the 2021 results had reversed these trends considerably with TMC resurfacing as a dominant force in most of these districts (except Darjeeling).

Table 2: 2021 Election Results in Bankura, Darjeeling, West Bardhaman, Purulia and Jhargram Districts

Source: Election Commission of India

Source: Election Commission of India

It might be a bit of an overstretch to say that TMC’s win as a regional party would lead to a strong opposition at the centre given the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) still holds about 336 seats (out of 543) at the Lok Sabha and 118 seats (out of 245) at the Rajya Sabha. However, given Mamata Banerjee’s massive win in the wake of rampant defection from TMC, and BJP’s campaign trails that included the Prime Minister and Home Minister visiting Bengal numerous times in the last few months—TMC’s victory is expected to consolidate the strength of regional parties to form a strong base in the run up to the 2024 Parliamentary elections, which was missing in the last few years.

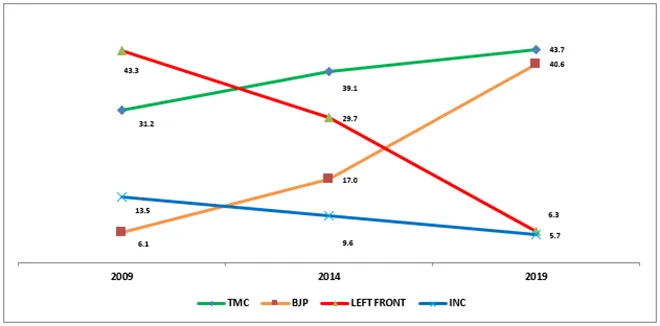

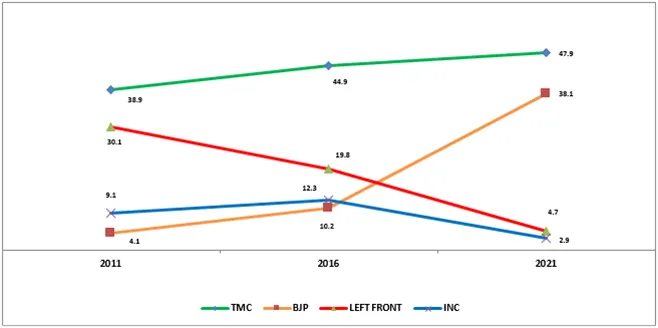

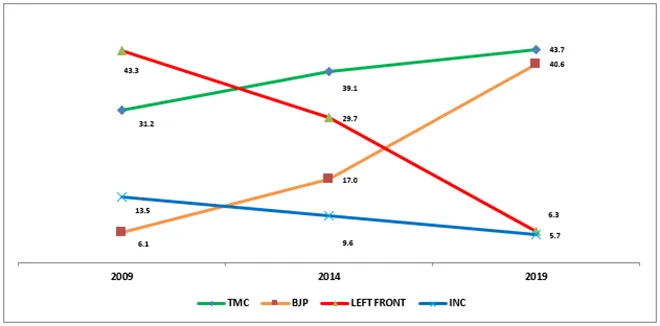

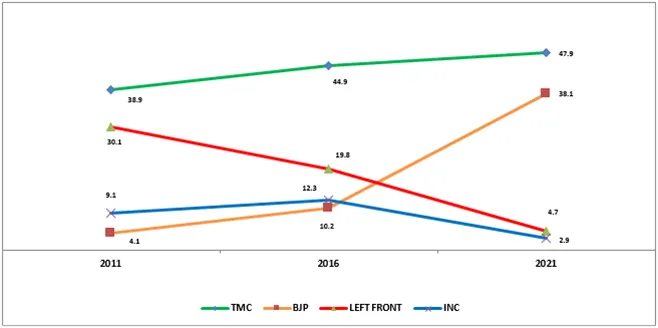

There is no doubt that the BJP has grown as a formidable force to be reckoned with in Bengal even before the elections, and their seat share have increased 26 times from 2016 to 2021 making them the main opposition party in the West Bengal assembly currently. Post India’s Independence, the traditionally strong parties, Congress and the Left have experienced an erosion of support over the years—to the extent that neither of the two parties could win even a single seat this time. Their combined vote share has dropped from approximately 56.8 percent in 2009 Lok Sabha elections to 7.7 percent in the 2021 Vidhan Sabha elections. In fact, this decline in support has also created an opportunity for the BJP to leverage the situation and expand its vote share in the state.

Figure 1: West Bengal’s Party-wise Vote Share (in percentage) in Lok Sabha Elections (2009, 2014 & 2019)

Source: Election Commission of India

Source: Election Commission of India

Figure 2: West Bengal’s Party-wise Vote Share (in percentage) in Vidhan Sabha Elections (2011, 2016 & 2021)

Source: Election Commission of India

Source: Election Commission of India

As Mamata Banerjee again took over as the Chief Minister on May 5, the newly-formed government in West Bengal needs to urgently tackle the COVID-19 crisis along with the post-poll violence that have allegedly erupted in various parts of Bengal. Although this should put an end to the politically charged atmosphere in the state since March, there is a series of by-elections that is expected to take place in the weeks to come. Additionally, the much-coveted Kolkata Municipal Corporation elections are also supposed to take place this year (postponed from 2020 due to the pandemic) that will also decide who becomes the mayor of the state’s capital. Finally, West Bengal has been a state that has found itself in the middle of centre-state feuds in the last five decades. As also emphasised by the Governor at the Chief Minster’s swearing-in ceremony on May 5, the direction this time must be towards a ‘cooperative’ (and not ‘conflictual’) brand of federalism to achieve the developmental objectives of the state and the nation in the longer horizon.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source:

Source:  Source:

Source:  Source:

Source:  Source:

Source:  PREV

PREV