-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

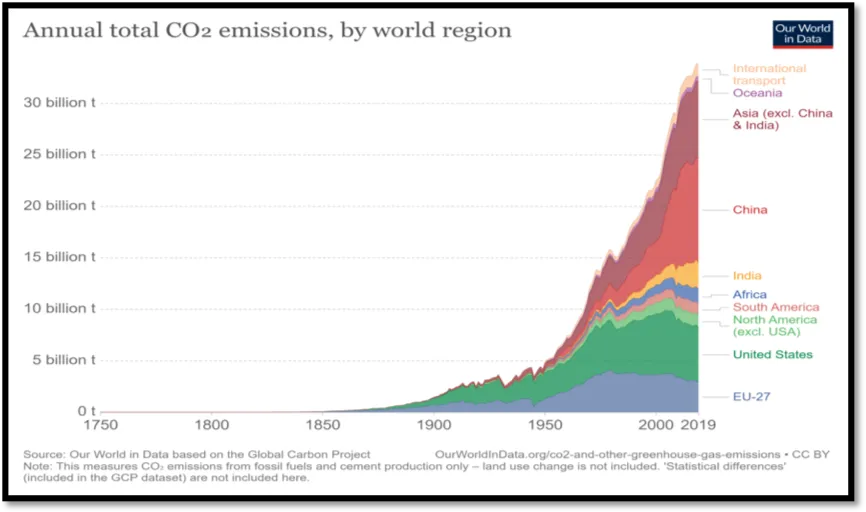

The Environmental Kuznets’ Curve hypothesis, popularised by The World Bank, on the growth-environment nexus envisaged climate action as an organic outcome of the processes of economic growth and development, achieved through improvements in energy efficiency and decarbonisation of consumption patterns. However, evidence on global carbon emissions suggest otherwise. In spite of economic growth, the annual total carbon dioxide emissions around the world have continued to rise, reaching up to more than 30 billion tonnes recently. The global emissions have significantly picked up since the 1980s, with the large Asian economies like China and India beginning their transition along the development spectrum.

Under the UN’s Sustainable Development framework, SDG 13 sets targets regarding emissions as well as climate finance for countries across the world to enable a transition to green growth. However, the global community has mostly fallen short of meeting these targets. In the year 2019, Asia was the largest emitter, contributing around 53 per cent to global carbon emissions—including China’s 9.8 billion tonnes of carbon emissions. Countries in North America and Europe have only recently started registering a slight decline in their total emissions level, with just the United States and the EU still contributing 15 per cent and 9.8 per cent to global carbon emissions. Even for countries in Africa and South America, the levels of carbon emissions have been declining, while for the fast growing economies in Asia, the emissions have been significantly higher and rising. This indicates that the decline in carbon emissions could primarily be due to a slowdown in growth rates of these countries around the world, and, not a sustainable outcome of deliberate climate action, which, as it appears, needs serious rethinking.

Even for countries in Africa and South America, the levels of carbon emissions have been declining, while for the fast growing economies in Asia, the emissions have been significantly higher and rising. This indicates that the decline in carbon emissions could primarily be due to a slowdown in growth rates of these countries around the world, and, not a sustainable outcome of deliberate climate action, which, as it appears, needs serious rethinking

Figure 1: Annual Global Carbon dioxide Emissions, by region

Source: Our World In Data, Global Change Data Lab

Source: Our World In Data, Global Change Data LabClearly, Asia appears to be the largest net emitter across the world today. This can be attributed to the spectacular economic growth achieved by these countries in the recent decades, leading to rising income levels, greater access to electricity and fuels, and, an overall improvement in standards of living. However, according to the shares in global cumulative emissions, North America and Europe have contributed nearly 971 billion tonnes of carbon emissions (approximately 62 per cent of global cumulative emissions) over the years, thereby, depleting the carbon budget of the world significantly. Therefore, while the developing countries may be large emitters today, most of the effects of climate change that the world is being subjected to are outcomes of unsustainable growth trajectories pursued by the developed nations in the past. Thus, these countries should ultimately have a larger stake in the responsibility for climate change mitigation.

While the developing countries may be large emitters today, most of the effects of climate change that the world is being subjected to are outcomes of unsustainable growth trajectories pursued by the developed nations in the past. Thus, these countries should ultimately have a larger stake in the responsibility for climate change mitigation

Moreover, as one looks deeper into the distribution of per capita emission levels today, a very interesting picture emerges. Asia’s population share in the world stands at nearly 60 per cent of the total population, considerably larger than North America and Europe. Countries like the United States, Australia and Canada have some of the highest levels of per capita emissions in the world, closely followed by countries like Germany, the Netherlands and Poland. Countries like France and the UK (with similar per capita income levels) have slightly lower levels of per capita emissions, close to the global average of 4.8 tonnes per person. This can be attributed to a deliberate change in the energy-mix of the nations through suitable policy actions and enabling infrastructure. Most Asian economies, except for China and Malaysia, have per capita emission levels close to or far below the global average. The oil-exporting countries of the Middle-East also have significantly high per-capita emissions levels but, owing to a relatively small population, a very low share in total global carbon emissions.

Additionally, as Table 1 below shows, comparing between countries across income groups in terms of their population shares and shares in global emissions, we observe stark inequalities in carbon footprints imitating the pattern of income inequality existing between them. This inequality in emissions when based on income distribution across individuals is even more pronounced.

Table 1: Shares in Global Carbon Emissions across Countries, by income groups

| Income group | Share of population (%) | Share of global CO₂ emissions (%) |

| High income | 16% | 39% |

| Upper-middle income | 35% | 48% |

| Lower-middle income | 40% | 13% |

| Low income | 9% | 0.4% |

Source: Our World In Data, Global Change Data Lab

While developing countries, concentrated mostly in the tropical regions, shoulder an unfair share of the burdens of climate change, there is a growing recognition of these existing inequalities in emissions distribution and the need for a more pro-active role to be played by the developed world. Even within nations, policies aimed at altering the energy-mix and mitigating effects of rising emissions level should be cognizant of the inequalities in carbon footprints across income groups. Any policy action should here be guided by the principles of the UNFCCC’s Common But Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR) framework, which specifically calls for climate action in accordance of due responsibilities and respective capabilities of the nations of the world.

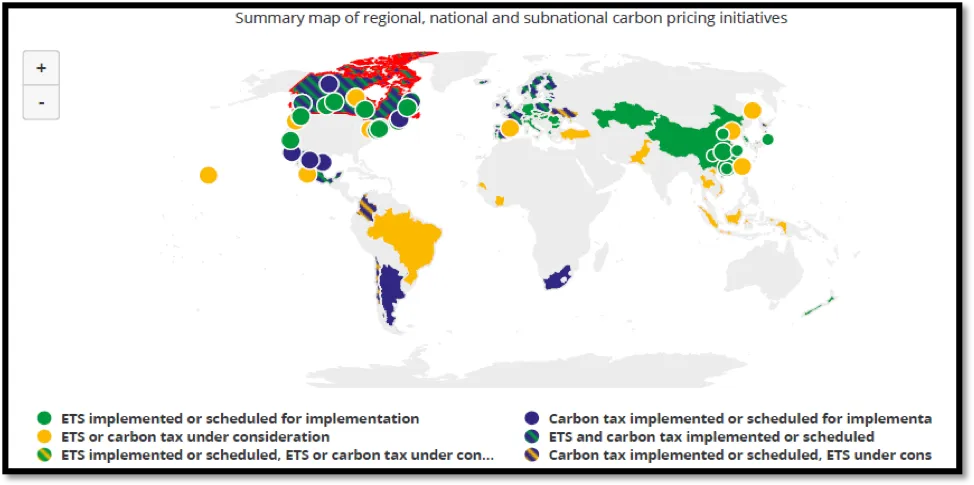

As an effort to reduce levels of domestic carbon emissions, as many as 42 countries around the world have implemented carbon pricing—through the Emissions Trading System (ETS) or through carbon taxes. However, there are large variations in the operative framework as well as the observed prices of carbon that are an outcome of these initiatives. For most countries, the carbon taxes imposed are fairly low compared to the recommendations of the High-Level Commission on Carbon Prices. Moreover, these efforts have largely remained concentrated in high income economies.

Figure 2: Regional, national and sub-national carbon pricing initiatives

Source: Carbon Pricing Dashboard, The World Bank

Source: Carbon Pricing Dashboard, The World BankEuropean countries like Finland and Sweden were among the first few to implement carbon pricing policies and these efforts have yielded results in terms of successfully altering the energy-mix of these nations. There has been a smooth transition to renewable energy sources and significant decline in energy efficiency and energy intensity of production. Canada has only recently implemented its revenue-neutral federal carbon tax policy, while the United States and Australia, some of the other largest per capita emitters are yet to follow suit.

Considering the rising global emissions level and the imminent dangers of global warming and extreme climatic conditions, a comprehensive plan for reduction in emissions and atmospheric carbon concentration involving both the developed and the developing countries of the world has become a necessity. Guided by the principles of equity, the framework of any such plan should revolve around ‘taxation-dividends-recycling’.

Considering the rising global emissions level and the imminent dangers of global warming and extreme climatic conditions, a comprehensive plan for reduction in emissions and atmospheric carbon concentration involving both the developed and the developing countries of the world has become a necessity. Guided by the principles of equity, the framework of any such plan should revolve around ‘taxation-dividends-recycling’.

Firstly, a global carbon tax can effectively de-incentivize the carbon-intensive production as well as consumption by internalizing the social costs of rising emissions levels. In fact, several economists at the International Monetary Fund have been proposing a tax of this nature. Besides, de-incentivizing and favourably altering the energy-mix, revenues generated from such a tax can also be useful in supporting public infrastructure development to facilitate a green transition. However, undoubtedly, a carbon tax, like any other energy tax, is extremely regressive in nature, putting excess burden upon the poor. Across countries, the excess burden of a global carbon tax upon the lower-middle or low income groups can be mitigated through climate action financing by the developed nations of the world. This should also be complemented by knowledge transfer on energy efficient technology of productions, R&D in climate action as well as use and generation of renewable energy. Within nations, particularly those like India, with high levels of income inequality, the bottom 40 per cent of the population should be compensated in terms of carbon dividends. Any such income transfer would protect the poor and vulnerable and increase the progressivity of the tax structure. Most estimates of such a tax-dividend policy indicate that the revenue generated by taxing carbon footprints and paying out a share of that revenue as dividends to the low-income earners would not only protect the vulnerable against poverty but also, leave enough resources for the public exchequer to facilitate a transition to green growth.

Lastly, a comprehensive framework should be developed for mapping the carbon footprints and the recycling capacity of the major carbon sinks of the world. The carbon emissions level and the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide are already significantly high. In such a situation, depletion of carbon sinks can effectively nullify any efforts at reducing emissions level through direct economic activities. Only recently it was reported that the Amazon rainforest- one of the largest carbon sinks of the world- has turned into a net carbon source. Exploring the role of public-private partnerships in facilitating the preservation of the carbon sinks of the world could also be a pivotal strategy. All these deliberate actions can take the world towards a more sustainable environment, through development cooperation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Debosmita Sarkar is an Associate Fellow with the SDGs and Inclusive Growth programme at the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy at Observer Research Foundation, India. Her ...

Read More +